Engaging with Vegetable Others

For Bennett, among others, the non-human is not just animal but what Bruno Latour describes as “actants”: all “things” that have the capacity to act as agents or forces with their own trajectories and tendencies.2 2 - Ibid. Bennett refers to Latour’s theory from his book The Politics of Nature (2004). This question stems from the larger — and admittedly complicated — project of decentring the human in the current anthropocentric era. To this end, the lowly plant is, both physically and conceptually, an excellent model and point of departure for exercising this decentralizing impulse.

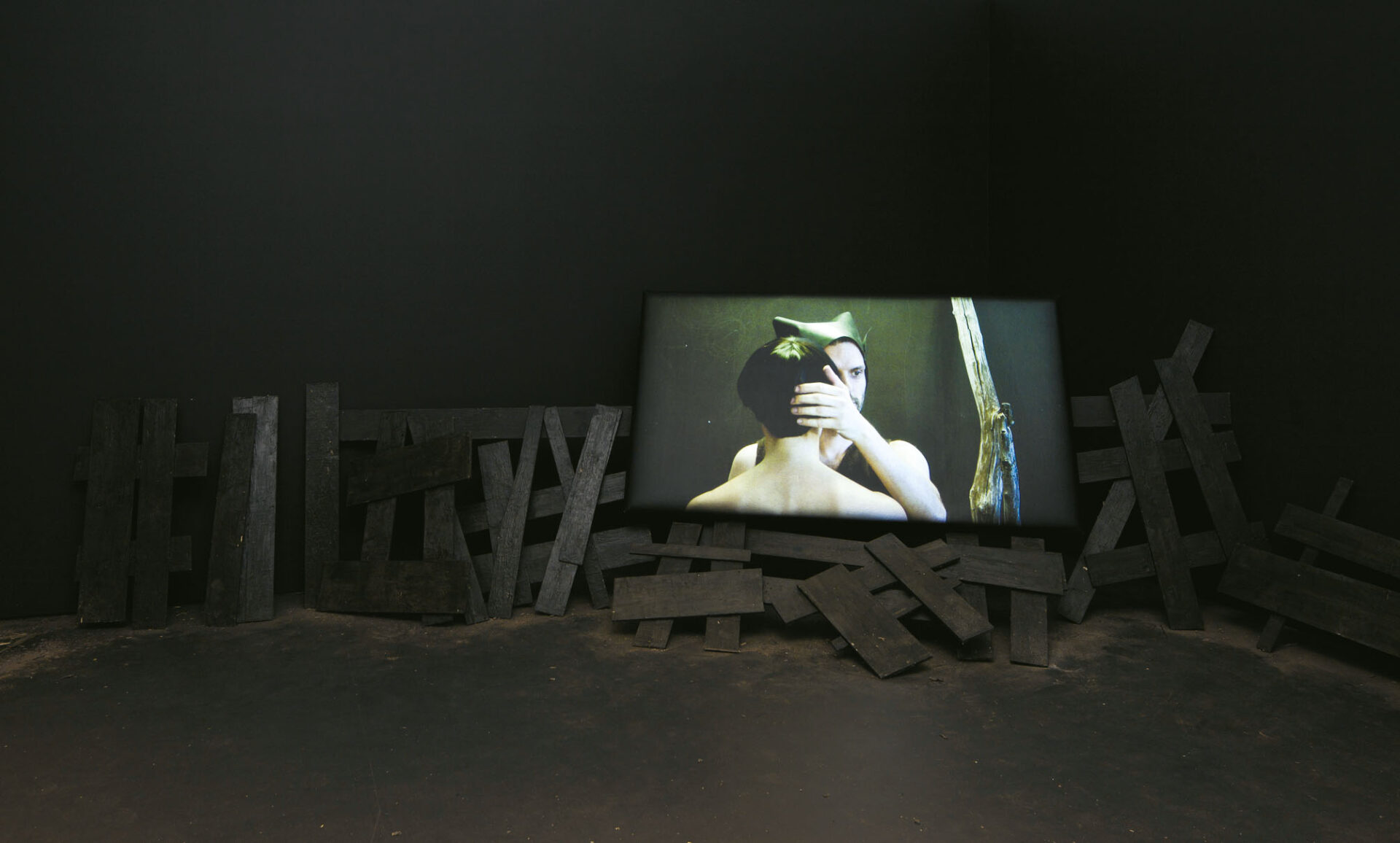

Your Disease Our Delicacy (Cuitlacoche), Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, Toronto, 2012–2016.

Photo : © Ron Benner

Our relationship with plant life is fundamental, and yet so are our differences. From the human position, understanding or relating to plant being, both as a distinct kingdom of life and as singular organisms, seems like an impossible task. Although individual plant bodies are decentralized, without a central node or “brain” as we understand it, plant communities are equally without human equivalent. In his book Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life, Michael Marder contends that plants are “capable, in their own fashion of accessing, influencing and being influenced by a world that does not overlap the human but that corresponds to the vegetal modes of dwelling in and on the earth.” 3 3 - Michael Marder, Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 8. Until recently, plants were often rendered invisible or secondary in our cultural imaginings, and were used as a background against which to explore human or animal concerns, a phenomenon known as plant blindness. By contrast, the recent “plant turn,” which is described by anthropologist Natasha Myers as a “swerve in attention to the fascinating lives of plants among philosophers, anthropologists, and popular science writers,” 4 4 - Natasha Myers, “Conversations on Plant Sensing: Notes from the Field,” NatureCulture 03 (2015): 35 — 66, http://natureculture.sakura.ne.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PDF-natureculture-03-03-conversations-on-plant-sensing.pdf. involves just such a shift away from the human-centred or animal world and toward a consideration of plant actants. This interest in looking at plants across a range of disciplines intersects with various ideas, such as plant being, thinking, and sensing. Many contemporary visual artists also seek to intervene in, and comment on, the connection between people and plants. Even if a project involving living plants is conceptualized as a metaphor for human issues, the material alone may speak to this cross-species connection. If a work is grown, not made, it requires the participation of plants in order to exist and necessarily brings them to the foreground, involving a measure of intersubjectivity between the artist, the viewer, and the plants that should be acknowledged as part of the piece.

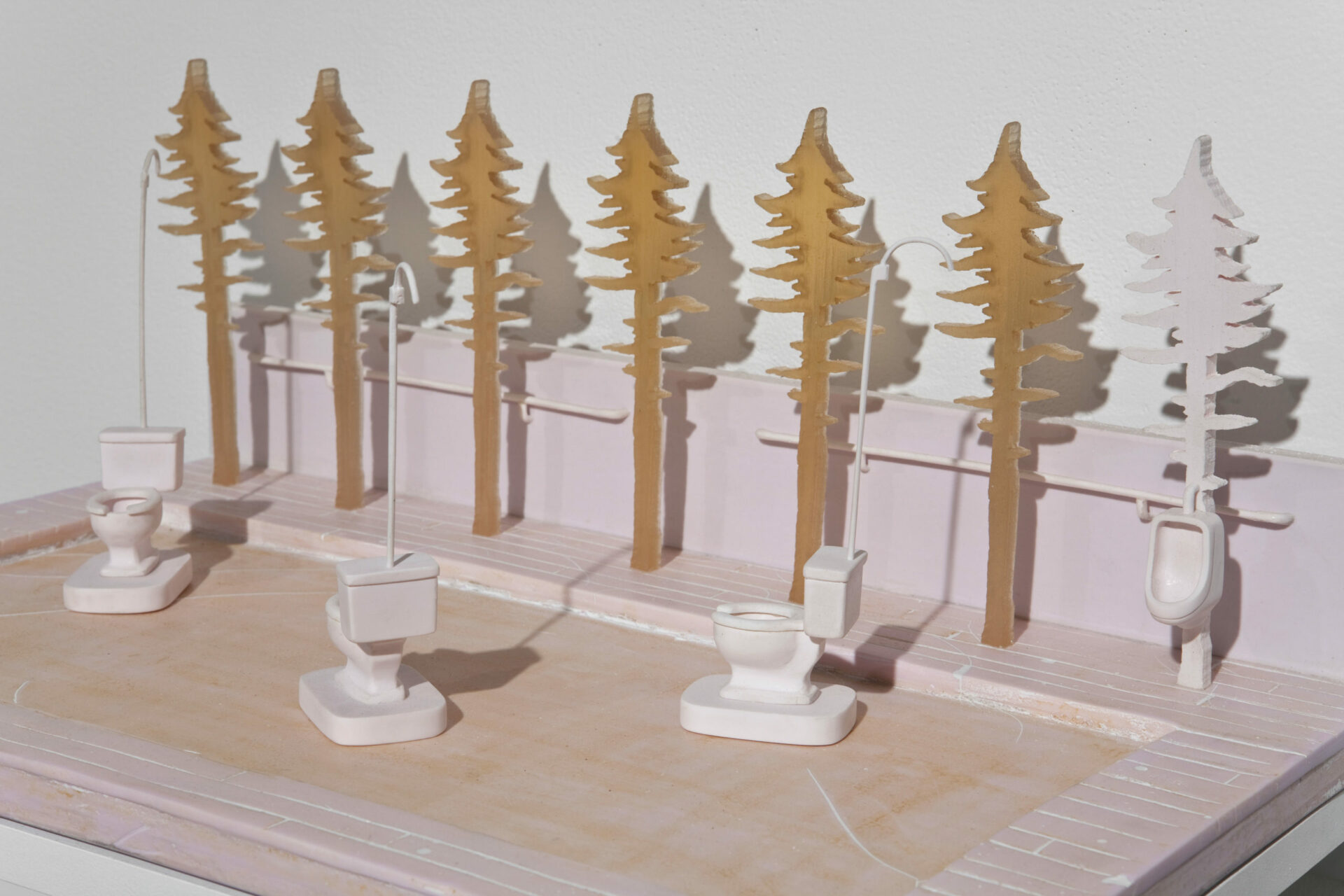

Wild Cube, Ruderal Enclosure – a Poetic Fieldwork, Innsbruck, 1991/1999.

Photo : Gerbert Weinberger, courtesy of the artist

Artistic production involving living things presents many limitations and challenges; in the case of plants, the work relies on their participation to varying degrees by requiring their presence or growth. Additionally, there is a loss of control inherent in the inclusion of living organisms in such a process, rendering the outcomes unpredictable. There are also ethical challenges; just as any community-based or socially engaged practice must consider ethical questions around its participants, so to must the participants be considered when the community includes non-human others.

In the 1982 Documenta 7 exhibition, German artist Joseph Beuys initiated the participatory project 7000 Oaks — City Forestation Instead of City Administration,in which seven thousand oak trees were planted across the city of Kassel, Germany, by Beuys and a multitude of volunteers. Over forty years later, this piece is still developing, as it takes sixty to eighty years for an oak tree to mature. Here, the work is produced on the time scale of plants rather than humans, as “the work lives and breathes with generations of people as they pass through life.” 5 5 - Ackroyd & Harvey, “Beuys’ Acorns,” Antennae 17 (2011): 63. Beuys intended for this work to function as a “social sculpture,” a term that he developed to describe a way of working in the social realm with the objective of transforming society. 7000 Oaks does have real, lasting effects on the community that it occupies by engaging with the interconnectedness of plants and humans in the urban ecology, transforming the biology and the design of the city space around the inclusion of these trees. Beuys’s concept of the social sculpture is acknowledged by many to be one of the precursors to the current social turn in contemporary art practices; the proliferation of artworks characterized by an emphasis on intersubjectivity, collectivity, and social interaction; and a motivation to “channel art’s symbolic capital towards constructive social change.” 6 6 - Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso, 2012), 12. In works such as 7000 Oaks, ecological concerns merge with social art practice, and the projects of decentralizing the artist and decentralizing the human are drawn together and converge.

Wild Cube, Ruderal Enclosure – a Poetic Fieldwork, Innsbruck, 1991/1999.

Photo : Gerbert Weinberger, courtesy of the artist

Participatory works in which the viewer physically engages with plants may work toward these forms of social change, and they may allow a deeper understanding of plant biological processes, which are nothing like our own. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of new media artists using various technologies toward these ends, such as using imaging technologies or biometric sensors to capture and visualize plant bio-data and act as translators. The collaborative interactive work Akousmaflore (2007), by France-based artists Grégory Lasserre & Anaïs met den Ancxt, is such a translation. Exhibited as a grid hanging from above, the plants in Akousmaflore create a symphony of sounds in reaction to human touch and proximity — a sonification of the electrostatic energy between humans and plants. Botanicalls, an ongoing project developed jointly by Rob Faludi, Kate Hartman, and Kati London in 2006, is another work involving translation through technology. Using moisture sensors and microcontrollers, Botanicalls enables plant individuals to send text messages, phone calls, or social media updates to let their human caregivers know when they need water.

Many theorists have suggested that visual differences, such as the absence of observable movement, are the most salient barriers to dismissal of culturally constructed distinctions of intelligence between plant and animal life.7 7 - Gunalan Nadarajan, “Phytodynamics and Plant Difference,” Leonardo Electronic Almanac 11, no. 10 (2003), accessed October 24, 2013, http://www.leoalmanac.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/LEA-v11-n10.pdf; Michael Pollan, “The Intelligent Plant,” The New Yorker, December 23, 2013, 92 — 105. Projects such as Akousmaflore and Botanicalls make the invisible biological processes of plants apparent and relatable by expressing animal-like qualities such as movement or sound, which we can understand and connect to.

Akousmaflore, Bòlit, Centre d’Art Contemporani, Gérone, 2011.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

To fully appreciate our anthropocentric worldview would be impossible; however, we can become more sympathetic by examining our interactions with other species more closely and attempting to relate. The Plant-Sex Consultancy, developed by Pei-Ying Lin, Dimitris Stamatis, Jasmina Weiss, and Špela Petrič in 2014, demonstrates an effort at this kind of relatability. The consultancy attempts to create an awareness of the reproductive needs of plants by proposing augmentations to supplement or enhance them. Each of the consultancy’s hypothetical products is developed with the needs of a specific plant species, or “client,” in mind. For example, a cyclamen flower that has relied solely on the frequency of vibrations emitted during visits by a now-extinct species of bee for pollination is fitted with a perfectly tuned vibrating apparatus, allowing it to release pollen onto other insects. The artists note that the anthropomorphism of the Plant Sex Consultancy is intentional; rather than being actual design solutions, the works function as critical tools aiming to respect and consider plant others.8 8 - Pei-Ying Lin, Dimitris Stamatis, Jasmina Weiss, and Špela Petricˇ, “Designing for the Non-Human Other,” accessed February 6, 2016, http://psx-consultancy.com/booklet/psx_consultancy.pdf. By creating a vegetal analogue for sex toys, the work emphasizes the common experience of reproductive sex across species.

PSX Consultancy sex toy concept, 2014.

Photo : Pei-Ying Lin & Dimitris Stamatis,

© Pei-Ying Lin, Dimitris Stamatis, Jasmina Weiss & Špela Petrič

PSX Consultancy,

installation view, BIO50, MAO, Ljubljana, 2014.

Photo : Pei-Ying Lin, © Pei-Ying Lin, Dimitris Stamatis, Jasmina Weiss & Špela Petrič

Our relationship with eating is another point of departure for this exercise in relating to the vegetal. Michael Marder suggests that how we eat — by dominating and devouring entire beings — is particularly symptomatic of our human-centred worldview. By contrast, for plants, eating is “a sort of receptivity, a channeling of the other, rather than an endeavor to swallow up its very otherness.” 9 9 - Michael Marder, “Is It Ethical to Eat Plants?,” Parallax 19, no. 1 (2013): 33. Marder considers the experience of eating like a plant, absorbing nourishment from the environment rather than consuming whole bodies. Diane Borsato similarly considered this notion in her performance work How to Eat Light (2003), in which she sat alone with a community of plants for the duration of their day, from dawn to dusk, attempting to learn from them. Her performance expresses both a desire to communicate with plants and the impossibility of understanding the lived experience of other species, acknowledging a potential wisdom and ability beyond our own.

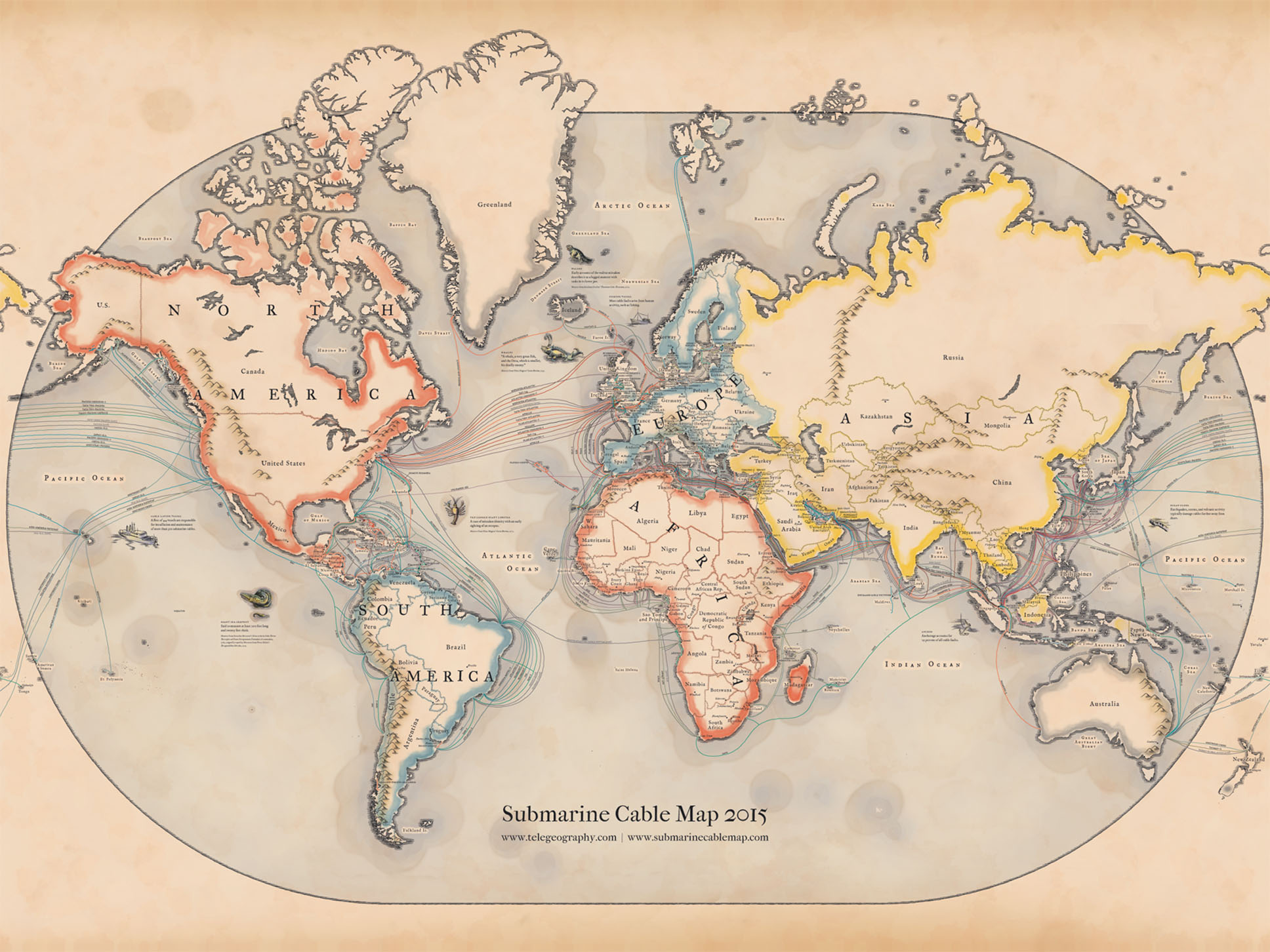

Before eating even occurs, there is the production of food, which is arguably the most fraught relationship between humans and plants. It is here that the messy politics of domestication, colonization, and genetic manipulation come into play. Canadian artist Ron Benner works with domesticated, captive plants, creating gardens in which he purposely cultivates select species in order to comment on the relationships between humans and their agricultural plant subjects. In a recent garden installation outside of the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery in Toronto, Your Disease Our Delicacy (cuitlacoche) (2012 – 15), images, texts, and plant life are combined in a garden that examines the locations and politics of both indigenous and introduced cultivated species. In this work, the focus is a fungal growth on corn that is considered a delicacy to some and a disease to others. Like much of Benner’s practice, this piece looks beyond the static position of plants as rooted in the soil and considers their participation in mobile aspects of human culture such as global capitalism and the legacy of colonialism, unearthing what our various geographies, histories, and migrations may reveal about our shared experiences with plants.

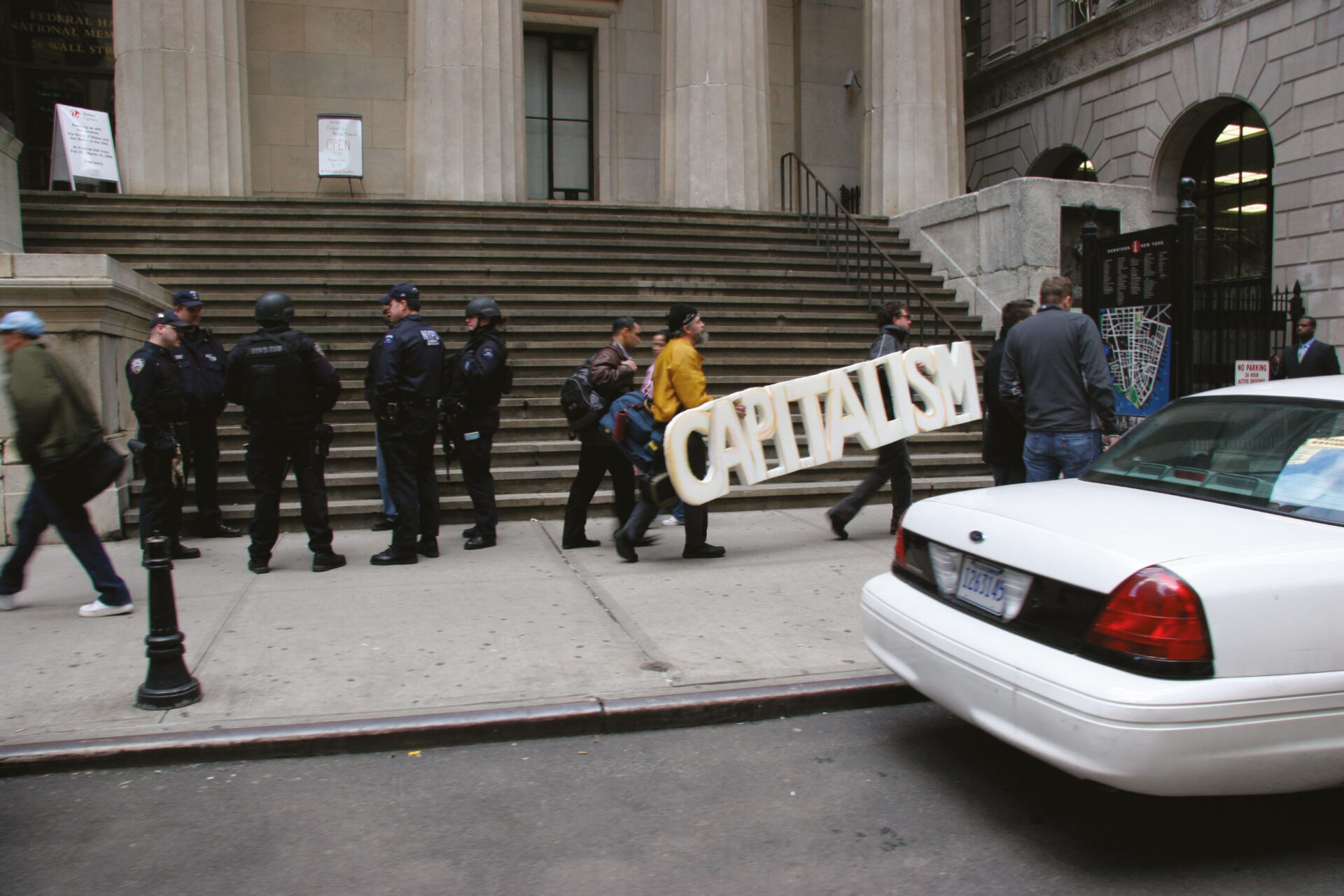

Burning and Walking, documenta X, Kassel, 1997.

Photo : Werner Maschmann, courtesy of the artist

Austrian artist Lois Weinberger’s work, on the other hand, represents a disruption in this narrative of subjugation, pointing to the collective political potential and power of the plant body. Referring to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome, Weinberger connects this concept to the way in which ruderal plants (what many would describe as common weeds) grow, migrate, and proliferate as a metaphor for human communities and forms of resistance against hierarchical systems. Weinberger’s “vegetable subversives” are the ever-present underclass of the plant-world, “the ‘multitude’ constantly threatening to rise up and disrupt the orderly regime of the city.” 10 10 - Tom Trevor, “The Three Ecologies,” in Lois Weinberger, ed. Philippe Van Cauteren (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2013), 217. In Weinberger’s public, site-specific installations, ruderals are provided with opportunities to take over spaces. An intervention in Salzburg in 1993 — which has since been re-enacted in other cities — titled Burning and Walking, involves breaking up the asphalt in a section of public space and revealing the earth underneath. No planting takes place. However, by opening up potential living spaces for these contested species, Weinberger facilitates their growth, relying on the will of plants themselves to arrive and complete the work, proving their ever-present and opportunistic nature. In the related series Wild Cube (1991/2011), Weinberger creates plant enclosures, “inverted” cages constructed to keep humans out rather than to keep plants in, placed over areas of exposed earth in public city spaces. The cubes are installed and then left to be repopulated by “plants who arrive by wind, birds or seeds already living in the earth.” 11 11 - Lois Weinberger, artist’s website, accessed June 23, 2015, http://www.loisweinberger.net/. Like Beuys’s 7000 Oaks, this work is decades in the making, relying on the timeline of plant lives to be fully realized. Whereas Benner’s plants are captives, Weinberger’s enact resistance to captivity, illustrating the tenuous superior position we hold over them.[consulté le 23 juin 2015]. [Trad. libre][/REF] ». À l’instar des 7000 chênes de Beuys, l’œuvre évoluera pendant des dizaines d’années et son achèvement sera tributaire du cycle vital des végétaux. Alors que les plantes de Benner sont captives, celles de Weinberger résistent à l’emprisonnement, illustrant la fragilité de la domination que nous exerçons sur le monde végétal.

Artists who engage with plant actants through social, collaborative, and participatory practices present us with various imaginings of plant being and alternatives to human-centred approaches by relying on the intersubjectivity of human-plant exchanges to realize their works. These projects and practices attempt to produce real relationships or effects by engaging directly with plant life, through interventions on the existing relationships between human and plant populations.