photo : Guy L’Heureux

What first appeals to us in Guillaume Lachapelle’s production is the prettiness of the sculptures and their childlike nature. The works produced in the various series Lachapelle has created since 2001 are micro-universes proffering ambiguous, overlapping elements of fantasy and realism. His work draws its strength from this ambiguity, which is also rendered as a tension between naturalist detail and improbable, stagey situations.

From one work to the next little dramas are revealed, showcasing domestic and urban scenes, populated mostly by strange characters and creatures. Each of these scenes seems an occasion to touch the spectator and to stir buried emotions. Lachapelle’s miniatures, rather than attempting to show such unperfectible worlds as city development programs or interior designs, consist of revealing the troubling undercurrents of the everyday, thus belying the familiarity and playfulness of one’s first impression on seeing the works.

43 x 56 x 36 cm, 2009.

photo : Guy L’Heureux

In L’avancée (2009), for instance, in a room whose quaintness is indicated by flowered wallpaper and outside walls of worn brick, a chair begins to move across the floor on its own. Electric lighting imparts the scene with a mood of mystery. Like other works in the same series, L’avancée was plunged in relative darkness at the time of its presentation in the exhibition En pure perte (2009).1 1 - The exhibition was presented in 2009, at Galerie Art Mûr (Montreal), which represents the artist. This new component in Lachapelle’s work becomes an intimate part of his pieces, amplifying their theatricality in this series. In prior work he used lighting indirectly, by way of the lighting systems in place at exhibition venues, playing on shadows cast around the sculptures. The quirky houses in his 2001 Structures de l’invisible series are illustrative, their open sides resting on precarious structures, lending them a skeletal appearance.

In their simple, handcrafted construction, these miniatures, which are often made of wood, have something in common with the language of surrealism. The sculptures are presented as façades, scaffolding, or ruins, which shadows complete and transfigure, revealing an otherwise invisible and unconscious reality. Lachapelle’s little scenes also touch on the absurd, which becomes a rather tangible reference in the later series, Passages avides, exhibited in 2004. The production hosts a menagerie of hybrid characters, like the rhinoceros-headed man in Rhino (2004), or the character with a rabbit head; and there are animals, including squirrels, and a dog whose snout has been replaced by wood moulding. This strange collection of zoomorphic alter egos suggests a study of human behaviour and adversity. The titles themselves are more than suggestive: L’aveu (The Confession), L’impasse (The Dead End), La chute de l’ange (The Angel’s Fall), L’œil torve du prince (The Prince’s Menacing Eye). The scenes are profoundly marked by a kind of desolation, their forlorn characters either sightless or fixed upon their predicament. The mood is cold and austere; indeed, even menacing.

photo : Guy L’Heureux

Troubling Fables

Lachapelle’s miniatures have something of the fable or children’s tale, but turned into a nightmare. The narrative potential in the artist’s production helps place this work in a perspective where the sculptures are not projections into the future so much as memories that are resurfacing and on which one must now cast a worried glance.

This bridge with the past and its reformulation in the present through models is reconfirmed in the 2006 series, Manèges. These slender sculptures recall previous works by Lachapelle. Here again, though more than before, supporting structures become an integral part of the work. The prevailing theme in these new little worlds is that of fairs or amusement parks, featuring carousels, little wagons, and contraptions on rails. Yet these rides hardly seem to promise the thrills for which they are normally sought. The few figurines who approach them testify, rather, to the fragile human condition. Besides, the sections of façade, the cornices, the mouldings, and other architectonic elements are visibly on the verge of being autonomous. In the near absence of human beings — who’ve likely fled, we’re tempted to think — one might believe they had a life of their own or were possessed by an evil genie. The impression is reinforced on observing the cockeyed nature of these obstinately and obviously peculiar structures. A merry-go-round, for instance, perched up high, can receive no one; rails go straight into the wall, are truncated at illogical places, small cars vainly line up along a cornice.

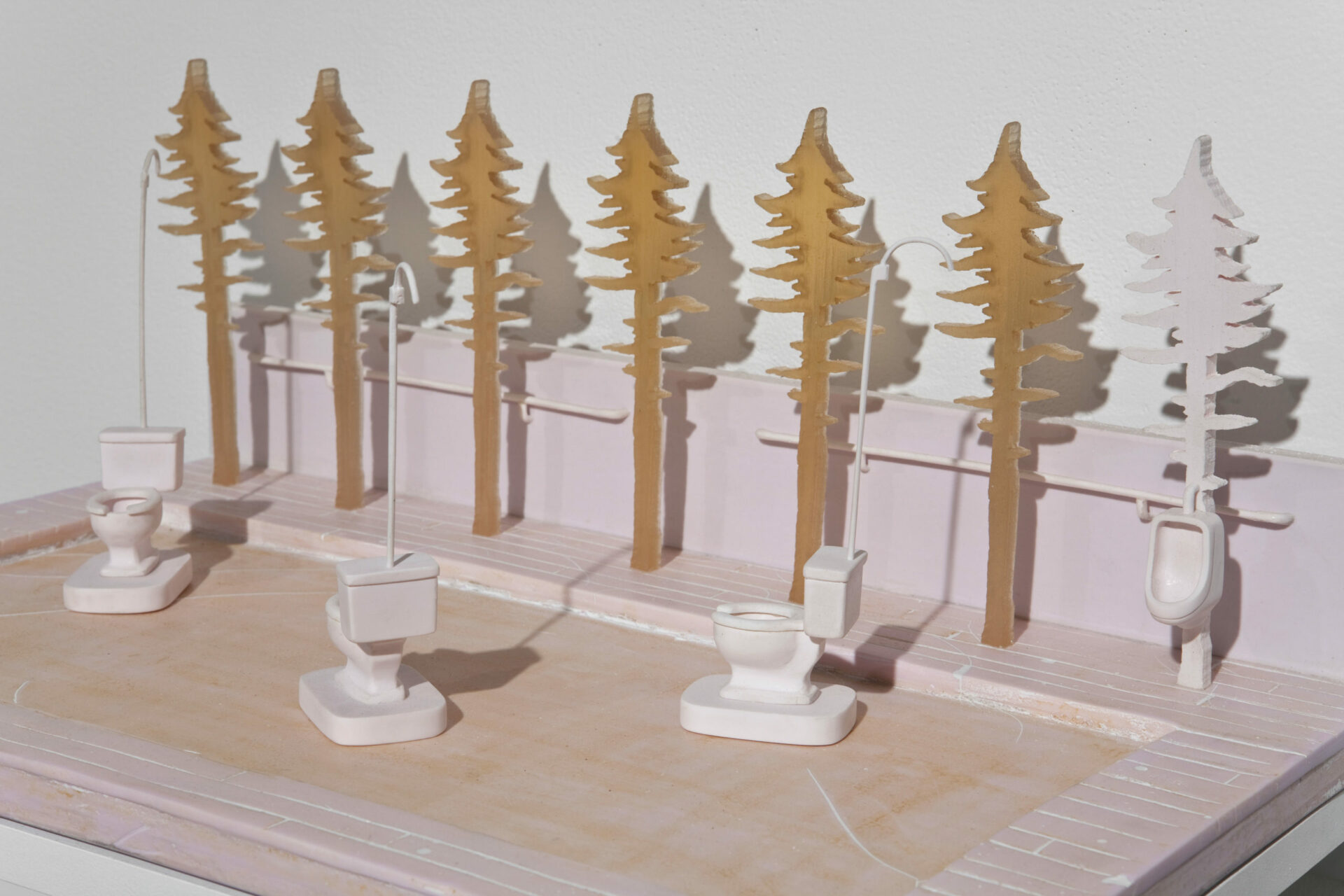

photo : Guillaume Lachapelle

Suggested trajectories through these miniatures are metaphors for journeys through the imagination and the unconscious. The smallness of the components makes possible this apprehension of otherwise ungraspable configurations (for it is hard to transpose such spaces). En pure perte (2009), another series, focuses on scenes that test our rational approach to space and its uses. It is all the more striking here, as the little wagons and bumper cars of previous series have been replaced with urinals, posted along a roadside under street lights, grafted onto a tree, or attached to the platform of a merry-go-round. With this motif, Lachapelle preserves the idea of seating furniture, but steers its playful function toward the humdrum, perhaps even the repellent. Les passeurs (2009) proposes a synthesis of these elements by marrying a merry-go-round with a columned gateway watched over by strange guards, hybrid animals who raise a part of the cornice to reveal a laden bookshelf.

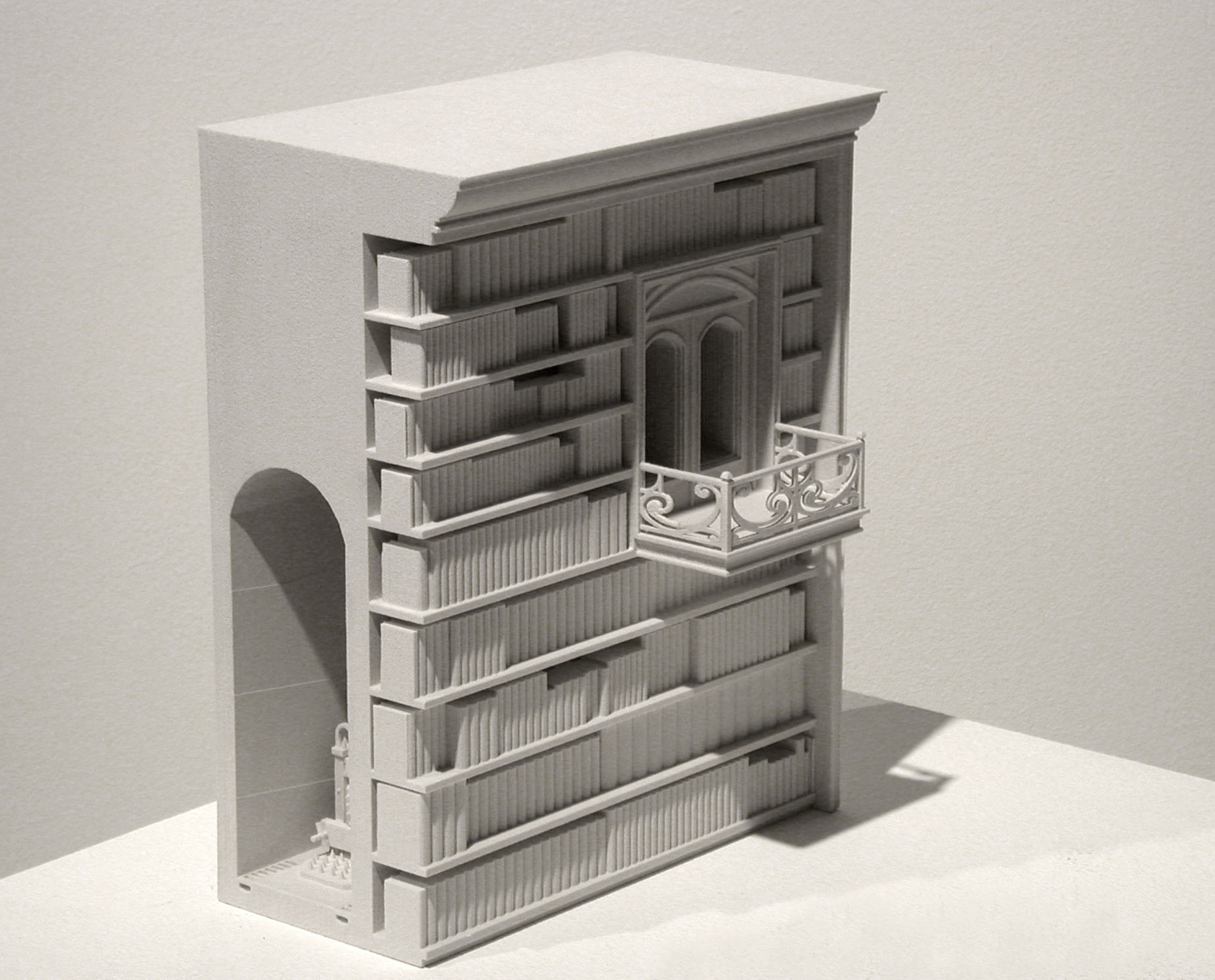

Lachapelle focuses the reading on the doorway and the books. With this staging of books, knowledge in its various forms, along with fiction, appear to become tokens of openness and of access to other realities. Elsewhere, however, the motif of the book and, by extension, the library — recurring motifs in Lachapelle’s work — is more ambivalent. In Antichambre (2009), for instance, a character is perched atop a bookcase while motorized partitions activate and reconfigure themselves in the room around him. The openwork partitions alternately close in on him and move away, their position always uncertain. The books also seem at once to engage and to cancel out a field of possibilities while producing a sense of collapse. This impression is reinforced by the character’s gesture of holding a book, while in fact empty-handed, and the replacement of his face with the façade of a building.

photo : Guy L’Heureux

Lachapelle’s pieces resist one’s effort to establish a clear typology of the spaces they represent, as these spaces tend to be mixed. Yet some stand out, allowing us to identify libraries, fairs, amusement parks, theatres. Thus, the spaces that captivate the artist, aside from their ability to figure the work of memory and emotion, recall those that Michel Foucault identified by the term heterotopia, spaces of otherness meant to receive our utopias.2 2 - Michel Foucault, “Des espaces autres (1967),” Dits et écrits, tome IV (Paris: Gallimard, NRF, 1984), 752-62. Available in English (and in French) online, July 15, 2010, at http://foucault.info/documents/heteroTopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en.html (translated by Jay Miskowiec) Among them, Foucault opposed libraries and fairs: the former were “heterotopias of indefinitely accumulating time,”3 3 - Ibid. while remaining outside of time themselves; the latter, on the contrary, are connected with the fleeting, passing time of festivity.

In 2009, Lachapelle stopped using wood and polyester resin, with which he produced his models, in favour of computer-aided modelling. His production is now drawn from this virtual work and printed in 3D, enabling him to explore volumes and configurations in unique ways by pushing the spatio-temporal limits of the library. In Fissure (2009), the library has become an infinitely and vertiginously malleable storage space of information, a problematization of spatiality that even the omniscient gaze overlooking the miniature now fails to grasp.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]