Photo : permission de l'artiste | courtesy of the artist

From Dance to Performance

When one thinks of the relationship between dance and the visual arts, the figures of Yvonne Rainer, Merce Cunningham, and Trisha Brown immediately come to mind. The standard bearers of postmodern American dance, these choreographers created works that were in some ways reminiscent of Kaprow’s “happenings,” during an effervescent period in the 1950s and 1960s when the visual and performing arts intersected around the hybrid, hard-to-define notion of performance. Although artists, dancers, and choreographers shared the similarly vague yet persistent intention of bringing art and life together from the early twentieth century on, they had each arrived at this stage of their creative thinking from very different places, and this had a decisive influence on the way they used “performance” to critique the boundaries of their respective disciplines. Laurent Goumarre’s characterization of performance seems particularly apt in this regard: “Whatever forms it has taken, performance has, throughout its history, periodically returned in order to point to an aesthetic and political crisis.”1 1 - Laurent Goumarre, “Tu n’as rien vu à Fontenay-aux-Roses,” Art Press 2, no. 7 (Nov. – Jan., 2008): 90 (Own translation). This statement concurs with that of RoseLee Goldberg, a well-known historian of performance art, who insists on its subversive or even provocative function inasmuch as it often emerges in reaction to an oppressive milieu and aims to surpass the limits of more established art forms.2 2 - RoseLee Goldberg, Performance: Live Art Since 1960 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 13.

For dance, this involved rejecting anything even remotely associated with representation. By refusing to submit to the dictates of narrative or emotion, by denying the illusion of facility and beauty created by technical virtuosity, and by trying to rethink the context in which works were to be presented, these choreographers and dancers wanted to make their mark beyond the codes of classical ballet. The work of redefining dance had already begun in the 1920s and 1930s by choreographers like Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, who believed that the purpose of dance was to inform audiences and spark reflection by addressing contemporary concerns, rather than simply seeking to entertain. This goal of bringing art and life closer together, which was initially conveyed through the content of the works, was much more evident in the form of choreographies starting in the 1950s, where daily gestures such as walking, breathing, and standing upright — gestures characterized as “found” à la Duchamp3 3 - Susan Au, Ballet and Modern Dance (London: Thames & Hudson, 1988), 161. — became the building blocks of increasingly abstract choreographies. This position was radicalized with the trend of postmodern American dance, which in eschewing all forms of expression in movement, ironically came much closer to the theories of modernism and art for art’s sake in the visual arts, focusing the entire dance experience on a study of form.4 4 - Sally Banes, “Introduction to the Wesleyan Paperback Edition,” in Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1987), xiv-xv. Thus, by distancing itself from everything related to representation, dance seemed to be moving closer to the visual arts. Yet to probe the connections between dance and performance in Julie Favreau’s work, it would seem more appropriate to think in opposite terms. While the choreographic gesture is the starting point for all of her work, she is interested in movement as much for its expressive potential as for its visual quality.

When Favreau talks about her work and approach, she spontaneously refers to the worlds of dance and film, and less to that of performance, with which she is nonetheless associated. Thus, it is the names of “non-dance” French choreographers such as Jérôme Bel and Boris Charmatz, places like the Ménagerie de verre and the Friche la Belle de Mai, or filmmakers like Roy Andersson and Andrei Tarkovsky that excite her most. One might assume that she does not see herself as part of the performance tradition — which conjures up the idea of the artist herself testing the limits of the body — but her position is, of course, far more nuanced. In truth, her approach is less a rejection of performance than a fascination with the expressiveness of a gesture and the body’s ability to convey a state of mind, a story, or to flesh out a character. It is a fascination that brings her approach closer to worlds traditionally associated with fiction and “live” representation: dance, film, and theatre.

Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 2011.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Julie Favreau : a Choreographic Approach

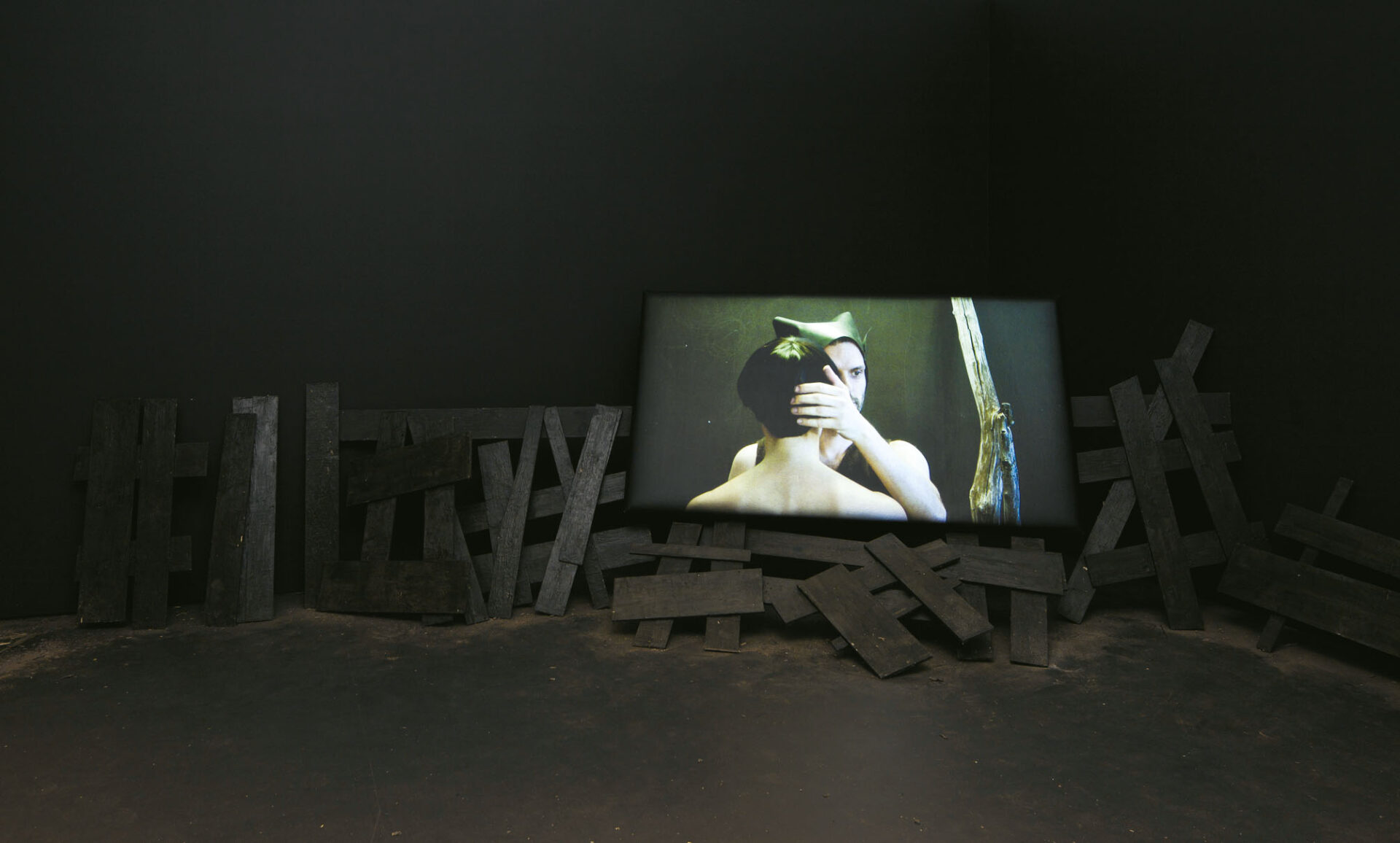

In watching “live art” shows during repeated stays in France in 2005 and 2006, including Christian Rizzo’s …/…(b) rencontre improvisée, Romeo Castellucci’s Hey Girl! and Loïc Touzé’s Love, Favreau discovered artistic productions on stage that could just as easily have been presented in an exhibition venue. That led her to envisage the exhibition space as a stage that could upset the codes of the “show” — notably the frontal aspect of the fourth wall, and the fixed time, place, and duration — while using familiar parameters (a set, a performer, and a “story”). How do the artist’s work and creative approach evoke or question the world of dance and the rules of the stage? I would suggest that Favreau’s is a hybrid approach that interrogates the conventions of both dance and performance. This approach has evolved through a series of projects: 8 personnages engagés pour peupler scénario de drame psychologique (Centre Clark, 2007), presented by Favreau as a “staging of performances in a gallery setting”; Leur cinéma (La Centrale, 2010) and Le manoir (Axenéo7, 2010), where the performers engage in “choreographic conversations with the objects around them”; Ernest Ferdik (MACM, 2011), which problematizes the installation by using it to present what was off-stage during the filmed performance;5 5 - or descriptions of Favreau’s projects: www.juliefavreau.com. and, finally, Antonel (Monument-National, 2012), part of Tangente’s IN LIMBO project initiated by choreographer Lynda Gaudreau, aimed at encouraging fundamental research in choreography.6 6 - Tangente: www.tangente.qc.ca/index.php? option=com_content&view=article& id=41.

Photo : Alexis Bellavance, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

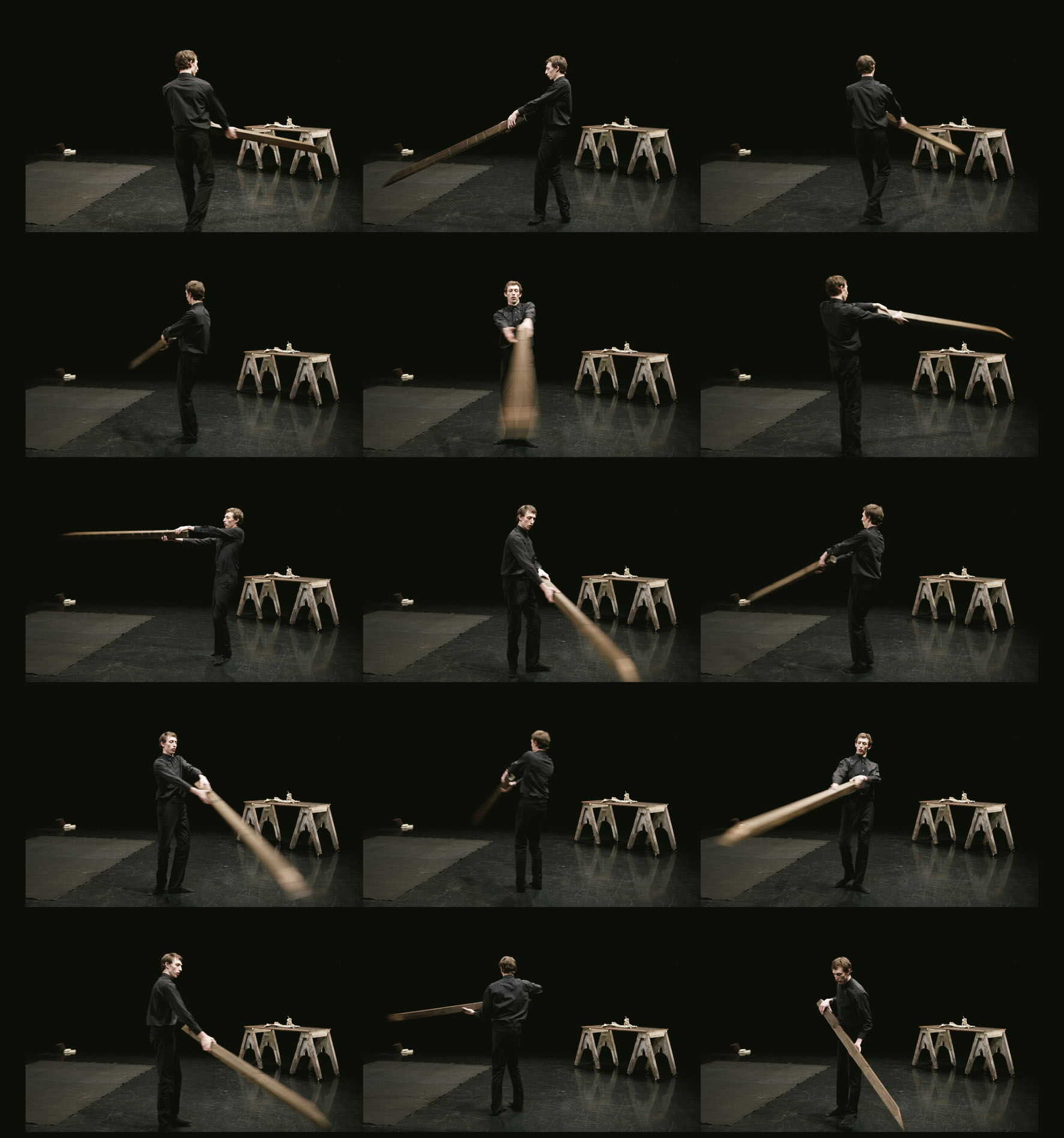

All of the works mentioned above involve a collaboration with dancers, actors, or performers. For each of her projects, Favreau carefully chooses the artists with whom she wants to work, according to their specific physical characteristics, in order to convey the movements and tensions she has in mind for the piece. Over the years, she has formed ties with collaborators who are familiar with her world and comfortable with the way she works. Her initial sources of inspiration are literary texts or films, which determine the narrative plot and suggest images, characters, movements, and objects able to convey the energy of a scene. Next comes the creation or choice of a set, a costume, and the arrangement of objects which are not simply accessories but are deliberately chosen for the movements they will be able to generate. (For Favreau, an object is never sufficient in and of itself: it always needs a gesture to release its narrative potential, becoming an artefact that is charged with the energy of the prior encounter.) Finally, there is the performance in the studio of previously imagined choreographic gestures, imbued with the idiosyncrasies of each performer. For example, for the Antonel project, dancer David Albert-Toth was an obvious choice. His physical strength, flexibility, and breakdancing skills allowed her to create a scene that would unfold beneath a large sheet of fabric. Albert-Toth produced sculptural forms as he moved, revealing an arm, a leg, or a foot in unexpected and unlikely places, given the shapes suggested by his movements. Here the dancer was both the object — an artistic device — and the subject — a physical agent who was actively participating, by virtue of who he is, in the creative act. All choreographic creations must grapple with this dual role.7 7 - Geisha Fontaine, “Objets de danse. Objets en tous genres,” La Part de l’Œil, no. 24 (2009): 104-105.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The issues of representation and expressiveness are also key to the artist’s practice, since she is always seeking to create characters whose psychological complexity is conveyed through the movements of the body as it interacts with objects in a given space. In this sense, her approach is reminiscent of the way Boris Charmatz envisages the dancer’s role as one that involves “rediscovering all of the psychological, lustful, sociological, political, and ethical nuances contained within a gesture.”8 8 - Boris Charmatz, “Extraits de trois conversations avec Isabelle Launay”: www.borischarmatz.org/node/413 (Own translation). Although the notion of presence, often discussed in theories of performance, is important for Favreau, she approaches it in a different way in her projects. Her goal is less to have spectators experience the here and now through the performer’s focus than to have them discover, in the freshness of a seemingly never-repeated gesture, the truth of an instant experienced in the present by the dancer. Thus, the idea of presence is tied to the intensity of gesture. In his or her performance, the dancer must move away from acting in order to more closely embody the true sensations of the present moment in dance. All of the tension in Favreau’s works lies in this uneasy relationship between representation and reality. By seeking to avoid the appearance of acting, she comes closer to performance and its desire to focus on the present moment. However, this moment is never original, since it is written and rehearsed in the studio. Whether it is filmed or performed live, the choreographic performance systematically complexifies this idea of a direct connection to the real, always experienced after the fact, since the choreography was constructed prior to the performance. Moreover, the artist ponders the connections between videographic writing, writing for an exhibition venue, and writing for the stage. In all three cases, rhythm is a key part of the editing process. The stage is like a video in the sense that both offer a single, frontal perspective, and changes in rhythm are planned. It is not the spectator’s movement in space that changes this rhythm. Video and stage performance are both closed and resolved propositions, whereas in an exhibition venue, works are more open and the rhythm more chaotic, as none of these parameters are entirely fixed.

Finally, Favreau’s works explore the stage as a malleable device that opens up a different physical and mental space — a fact tacitly accepted by the spectator who is accustomed to the codes of a “show” (dance or theatre). Her works blend two types of expectations, proposing a give-and-take between two traditions. Whereas in 8 personnages and Antonel, she maintains the fourth wall, and with it the frontal view and the distance it creates, in her immersive installations Le manoir and Ernest Ferdik, spectators are completely drawn into the setting and are free to walk around it. The context in which the performance is presented has a direct impact on the way in which time is envisaged, a variable that is taken into account during the writing of the choreography. While works such as 8 personnages and Antonel are scheduled at a specific time for a set duration, in the case of the installation, spectators can come and go as they please.

In short, it is perhaps in the process rather than the result that the connections between “live art,” dance and performance are best appreciated in Favreau’s work. Her position as a choreographer is different from that of a stage or film director, since her primary material continues to be the gesture and movement of the body in space, not the text. It is therefore less the result than the point of departure — her relationship to the act of creating — that makes a difference. Performance is an attitude of the present; dance, a writing of gesture, and the choreographic performance a skilful combination of the two.

[Translated from the French by Vanessa Nicolai]