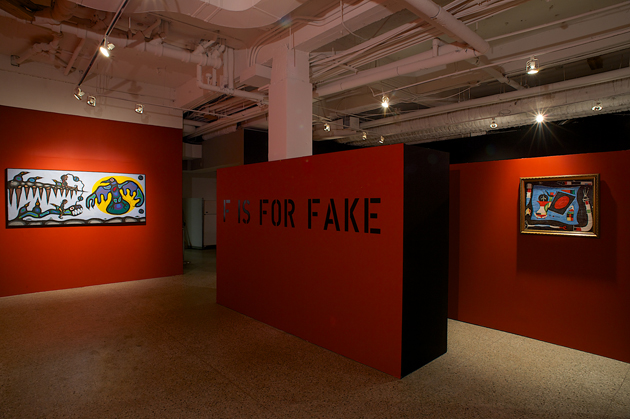

Photo : Alessandro Wang, courtesy of ShanghART Gallery, Shangha

Holzwege, the title for the inaugural exhibition of ShanghART’s new gallery along Shanghai’s West Bund, is taken from a book of six essays by Martin Heidegger, most recently translated into English as Off the Beaten Track (2002), which includes one of his most famous essays, “The Origin of the Work of Art” (1935–37). “Holzwege” denotes a path in the forest that only a woodsman would recognize, not one that has been cleared, but rather formed naturally. “Off the beaten track” suggests a journey taken by those skillful enough to see the path that lay before them, but perhaps the French translation of Heidegger’s book (a title he purportedly endorsed) is equally instructive: Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part (1962), “paths that lead nowhere.”

Create your free profile or log in now to read the full text!

My Account