Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In some ways, Mathieu Latulippe’s exhibition Retour à Paradise Lost1 1 - Mathieu Latulippe, Retour à Paradise Lost, Optica, un centre d’art contemporain, May 17 to June 28, 2014.(Return to Paradise Lost) seems to invite viewers to note the presence of traditional Christian relics in Quebecers’ conception of the world. Given the debates over exactly where laicity fits into contemporary Québec society, such an initiative may prove to be quite timely. However, there is no clear indication that Latulippe wishes to engage in this debate or that he is encouraging a renewed relationship with religious heritage. Even though the title of the exhibition asks us to reflect on how certain religious ideas are positioned in the cultural imagination, pointing out the associations between paradise and the idea of the fall, redemption, guilt, and the Apocalypse, there is no question of establishing a sort of underlying inventory of the concepts and sacred figures in this presentation of Latulippe’s recent work. Rather, it seems more relevant to contemplate the meaning of the word “retour” (return) in the exhibition’s title.

sans titre [godzilla – 1998], 2013.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Although the title might lead us to believe that we will return to the Garden of Eden, we observe, when we enter the gallery, that Eden is nowhere in sight. With the imposing work Shit Happens # 1, to our right, and Welcome to Fabulous Paradise Lost, to our left, we understand that the paradise in question is of a different kind, probably more allusive, more conceptual. And when we look at the latter work, with its graphics and lettering typical of motel signs, we realize that Latulippe is inviting us on a road trip whose destination is not yet clear. It seems less about returning to places we once knew than about travelling through worlds both fascinating and disturbing — worlds seemingly affected by natural and technical catastrophes or characterized by wild, untamed nature; worlds that seem as disquieting as they do ideal; and worlds that mostly exude a strange impression of déjà-vu. It might be a good idea to recall here that in 2012, Latulippe devoted a large part of a creative residency2 2 - Si l’on considère la liste des films répertoriés, c’est au minimum une centaine d’heures que l’artiste a consacrées au visionnement des films. to watching science fiction, fantasy, and horror films 3 3 - This is the crossover program Résidence de recherche jeune création Montréal – Valence (France) between Optica and art3. focusing on the theme of the end of the world.4 4 - On this end-of-the-world movie theme, see Peter Szendy, L’Apocalypse cinéma. 2012 et autres fins du monde(Capricci, 2012). . He then classified the images according to the types of representations of nature found in productions of this kind and collated them (160 photograms taken from films), without commentary, in Visions [Documents de recherche]. Thus, it comes as no great surprise that the exhibition contains reproductions of sunsets drawn from this type of film — in the works Sans titre [Godzilla – 1998] [Godzilla – 1998] and Sans titre [Jaws] [Jaws] — or a segment of the sound track of Night of the Living Dead (1968) ; nor is it surprising that certain components of the works seem recognizable. In fact, the minimalist white structure of Shit Happens # 1 is formally linked as much with the structure upon which the flocks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) were assembled as with Sol Lewitt’s modular structures. Through the use of such cult movies, Latulippe reveals the constant oscillation between the notions of the sublime and of mesmerizing terror that run through his work.

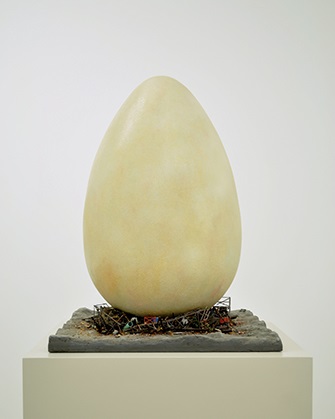

Baby Blues, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

shit happens #1, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

This aesthetic tendency is evident in works such as Baby Blues and Shit Happens # 2, which are particularly unsettling: the first is a nest, composed of immense pieces of industrial debris, holding a gigantic egg; the second consists of a car completely covered with bird droppings. But not all of Latulippe’s representations of nature are this negative, as we can see in Il était une foi and Monument [La petite maison dans la vallée], which nods to utopian models based on the harmonious cohabitation of the wild and the civilized. However, the most interesting representations, but also the most ambiguous, are those articulated, at first glance, around the experience of the sublime — that is, they induce, in the viewer’s mind, the idea of the infinite, the unmeasurable — but that, after a moment of observation, raise concerns. Examples are La chute, a view of Niagara Falls5 5 - For an overview of the sublime nature of the Niagara Falls, see François-Marc Gagnon, “La forêt, le Niagara et le sublime,” in Grandeur nature: peinture et photographie des paysages américains et canadiens de 1860 à 1918 (Montréal: Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 2009), 33 – 36. 33-36. from which fog in the form of a mushroom cloud rises, and No 3 [Blue, Yellow, Orange on Deep Black], in which an immense sky is studded with artificial satellites rather than the stars that one might expect to see. Some of these works

Monument [La petite Maison dans la vallée], 2013.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

La chute, 2013.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Shit happens #2, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Some of these works give the impression that Latulippe is reviving the preoccupations and concepts of romantic artists, who saw art as a means of access to knowledge and a way of making the invisible visible. They even advocated a religion of art, in which “God comes to the artwork due to the idealistic nature of the creative act.”6 6 - Olivier Schefer, “Religion de l’art et modernité,” in Traces du sacré (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2008), 46 (our translation). 46.This vision of art has been largely abandoned today, but it seems that Latulippe nevertheless draws on it. Although he distances himself from the romantic artists’ most prized representations and the messianic model that they promoted, he has preserved, among other things, the idea of Kunstchaos, “the only response that romanticism can bring to the disenchantment of the world.”7 7 - Pierre Wat, Naissance de l’art romantique. Peinture et théorie de l’imitation en Allemagne et en Angleterre, Paris, Flammarion, 1998, 118 (our translation). 118. As Pierre Wat notes, “Romantic artists are those who make artworks from disorganization”8 8 - Ibid., 113 (our translation). 113. — the only way to oppose all forms of systematic structure, which always aims to eliminate incompatibilities. Beyond the contrast between kitsch figure and minimal structure, “outsider” art and cultural mass production, tragedy and comedy, what emanates from Latulippe’s works is the impression of a chaotic world that takes hold of visitors to the exhibition, as evidenced by its critical reception. The evocation of a world in ruins, through a series of snapshots or stations, inspires a sense of joyous disorder. This gathering of fragmentary shocks, presented as an artificial and creative chaos, makes visitors aware that not all is well in the world. It seems that Latulippe is intent not on establishing a neo-romantic project, but, through this ordered chaos, on experimenting with a semblance of unity in a failing world.

[Translated from the French by Käthe Roth]