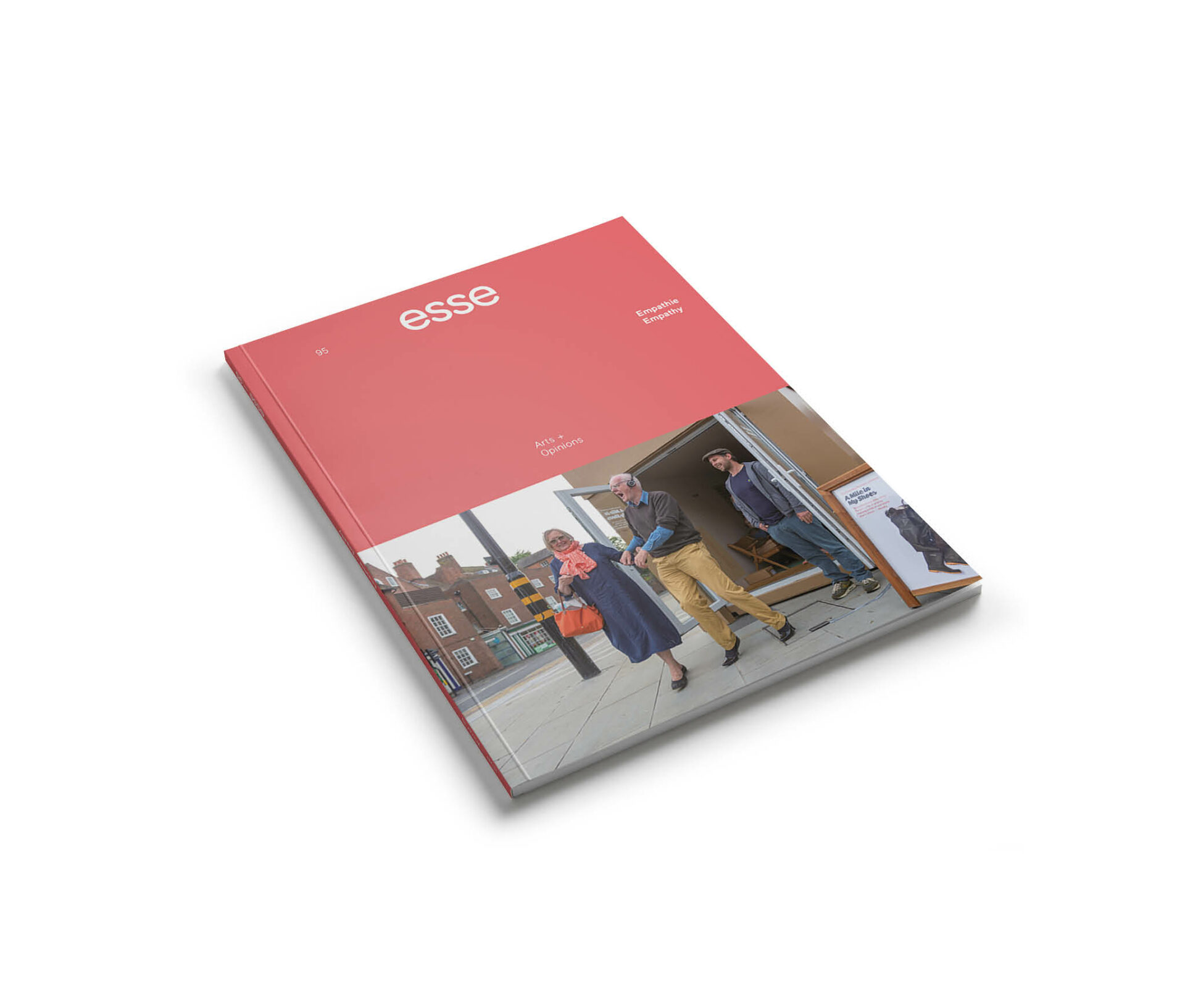

Empathy Museum’s A Mile in My Shoes, KIKK Festival, Namur, 2017.

Photo : Simon Fusillier

In the introductory pages of Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), Bronisław Malinowski, who sojourned with the Trobrianders of New Guinea on numerous occasions, celebrated the power of ethnography in these terms: “What is then this ethnographer’s magic, by which he is able to evoke the real spirit of the natives, the true picture of tribal life?”1 1 - Bronislaw Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea (London: Routledge,1978), 5. This magical art capable of penetrating the deepest layers of Indigenous existence, this supposed superpower of the ethnographer — in this case, Malinowski himself — recalls, in many respects, the figure of the empath, popular in contemporary science fiction; this “empathic” being, gifted with hypersensitivity, slips telepathically into people’s private spheres to reveal the most intimate of truths.2 2 - The protagonist in the film Code 46 (2003), by Michael Winterbottom, offers a good example. Beyond science fiction, some individuals identify as “empaths,” demanding significant sums for their consultation services, similar to those of a medium. For more on this subject, see Richard Godwin, “‘It’s a Superpower’: Meet the Empaths Paid to Read Your Mind,” The Guardian, June 24, 2017, www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/24/superpower-empaths-paid-read-mind-empathy. This fundamental and widespread acceptation of empathy as the fantasy of having direct access to other people’s states of mind persists, not without the risk of potential abuses, including those of outright projection and the illusion of transparency.

Empathy Museum’s A Mile in My Shoes, KIKK Festival, Namur, 2017.

Photo : Simon Fusillier

In Athens in 2013, philosopher Roman Krznaric presented the TED talk “How to Start an Empathy Revolution,” based on his book published a few months earlier.3 3 - See Roman Krznaric, “How to Start an Empathy Revolution,” filmed January 2013 in Athens, Greece, TEDx video, 17:14, www.youtube.com/watch? v=RT5X6NIJR88; Roman Krznaric, Empathy: A Handbook for Revolution (London: Rider Books, 2015). In Krznaric’s view, empathy constitutes a possible antidote both to the hyper-individualism of neoliberal capitalist societies and to world conflicts. Based on the conviction that socio-political revolution is possible through empathy, in 2015, Krznaric founded the Empathy Museum,4 4 - Visit the museum’s website at www.empathymuseum.com. an organization without fixed location dedicated to participatory arts projects aimed at expanding our understanding of others. For example, the project A Mile in My Shoes by artist and director of the museum Clare Patey consists of a shoe shop, housed in a giant shoebox, from which the public is invited to walk a mile in a pair of shoes of their choice while listening to the story of the shoes’ original owner. Although the Empathy Museum clearly expresses the noble desire for a shared humanity, I find it hard to believe that such projects can spark a revolution that would cause a sea change in how we live together.

The problem lies not in whether one may, or may not, be moved by listening to such stories, but in the prescription of empathy as a universal (and universalizing) remedy.

Through this work, as the title suggests, Patey literally invites the public to put [themselves] in someone else’s shoes, suggesting that empathy is an art, the capacity to put oneself in the place of others in order to understand their ideas, feel their emotions, and understand their experiences. Yet, this humanist conception presupposes the transparency of the other (and the self), while perpetuating the illusion that grasping one another in a gesture of integrity is possible. As Édouard Glissant eloquently observed, the verb to grasp implies “the movement of hands that grab their surroundings and bring them back to themselves. A gesture of enclosure if not appropriation,”5 5 - Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 191 — 92. which, rather than opening up the possibility for relationship, severely reduces potentialities and promotes a clichéd sensibility, resulting in a “social bond” devoid of poetry. It was in that vein that Glissant insisted on the right to opacity: the right of individuals to remain “opaque,” to preserve zones of unknowing irreducible to any attempts at categorization. Accordingly, if it is not a question of grasping others, how are we to conceive of empathy beyond the limits of consciousness and subjectivity, at the confluence of our respective existential opacities? Perhaps by means of a poetics of relation, evident in numerous artistic practices. Deviating from the transparentist quest characteristic of our times, how can these practices engage a more nuanced and complex relationship with the world, one that folds and unfolds to the rhythm of our vital energies?

Resonance of Body-Movement

For several years, Brazilian artist and researcher Mariana Marcassa has been developing a therapeutic performative practice anchored in the relationship between the voice and the body’s memory of trauma. Marcassa has conducted extensive research on banzo, a depressive state that afflicted African slaves brought to Brazil — and that still affects their descendants today. Her research led her to the Sertão Mineiro region of northwest Brazil, where she explored the various sonorities (yells, cries, chants, and other vocal expressions) of this pain, which inflicts the body with a sense of powerlessness, “an absolute non-life-power.”6 6 - For more on the artist, visit https://cargocollective.com/marianamarcassa/banzo-sounds. The organic anaesthesia that ensues hinders any regenerative potential in those struggling with the rampant effects of banzo, causing apathy, depression, and even suicide. It is a carnal affliction directly associated with the endemic effects of colonial slavery, which, according to Marcassa, is distinct from the notion of melancholy as defined in the West. How can we access this experience? How can we resist the temptation to identify with it, to “grasp” it? What we can feel, what we can truly capture, are the forces that prevail in the shouts, cries, and chants. Here, banzo is envisaged as a sound affliction, unascribable to a specific individual, an extraneous sensory force that has captured the spirit of beings and things for five centuries, and more acutely in some regions of Brazil than others. In this sense, Marcassa’s approach diverges from the therapies of classical psychology, rooted as they are in clinical practices often based on a segmentation of body, mind, and environment. Related to this research, Marcassa has elaborated several solo and collective performances, as part of her thesis in clinical psychology at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, under the direction of Suely Rolnik. This work has also inspired her to broaden the scope of her research into other areas of human suffering, deepening her exploration of the relational, using the act of listening as a means for creating a space of resonance that reflects our capacity to affect and be affected.

In the exhibition Seances for Living organized by Montreal’s SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art, Marcassa presented Voicing Another Spirit, which took the form of thirty- to forty-minute individual seances, arranged by prior appointment. She took over a corner of the gallery: she put a carpet on the floor, curtained the area off with a white sheet for intimacy, and surrounded herself with numerous objects, such as large bags filled with water, candles, and musical instruments (including a blowing horn, singing bowl, xylophone, ocean drum, and maracas). At the beginning of the session in which I participated, the artist explained that together we would activate a process of sensory exploration, mediated by sound objects, with a view to liberating obstructed bodily memories. Each seance unfolds in a unique manner depending on the energy in the environment — between her, the objects, and the person involved; as no precise protocol predetermines the progression of the encounter, one enters a realm of uncertainty, without knowing how one will emerge.

Voicing Another Spirit, performance, SBC Galerie d’art contemporain, Montréal, 2018.

Photos : Clara Lacasse

Inspired by Lygia Clark and her radical experiments beginning in the 1970s with Structuring the Self, Marcassa’s practice focuses on non-verbal communication that allows for the emergence of affects, those intense forces traversing all beings. We are indeed here, together, on a sensory plane that always overwhelms and challenges us7 7 - It’s important to note that Marcassa’s practice is not restricted to the institutional art circuit. She offers seances in her studio to facilitate the ongoing nature of her research. — resonance of bodies, magic…. In these conditions, one moves away from the logic of identity (and identification) to contemplate the processes of singularization that engender relation, in the sense that Glissant understood it: as a mutual rapport composed in and of uncertainty, as opposed to determinism. What is important, then, is the active shaping (Gestaltung) of relation through the coexistence of opacities that weave fabrics: “To understand these truly one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components.”8 8 - Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 190.

Corps à corps

It is from this perspective on the relational, in the fullest sense of the term, that ethnologist Jeanne Favret-Saada envisaged her fieldwork on witchcraft in rural northwest France between 1969 and 1972. By the end of the 1980s, countering participatory observation and empathy, she was demanding that “affective states devoid of representation” be taken into account in the field of ethnography. So that empiricist anthropology could finally break with the assumption of the essential transparency of human subjects to themselves (and others), the affective intensity accompanying situations of involuntary and non-intentional communication should, in Favret-Saada’s view, be granted epistemological status. It is not a matter of putting oneself in the place of others, but of placing oneself, or being assigned a place, at the heart of a community, where one can experience the forces and their effects at play. “‘Participating’ and being affected are categorically not techniques for the acquisition of knowledge via empathy, however one defines it.”9 9 - Jeanne Favret-Saada, “Being affected,” trans. Mylene Hengen and Matthew Carey, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2, no. 1 (2012): 441. Rather, it is a reciprocal affection, an exchange cloaked in mystery, in the sense that one can never truly perceive the images that, for the other and only the other, are associated with the forces at play.

The non-represented affect that Favret-Saada advocated, the energetic charge which circulates and encompasses us, opens up the possibility for sensitivity and its powers of connection.

The video performance Corps à corps10 10 - An English version exists, titled Close-Combat (2016) and interpreted by Inka Ernst, member of the feminist collective TEN. (2015), created by Louisa Babari and Célio Paillard, creates a space of resonance, transmitting the affects of colonial revolt. In the video, Paillard interprets Fanon, le corps à corps colonial, a text by philosopher Seloua Luste Boulbina that addresses the psychiatric practice of Frantz Fanon while he was administering a hospital in Bilda, Algeria. It was at that time that Fanon observed the degree to which the war and colonial domination traversed the bodies of colonialized peoples. Paillard embodies Boulbina’s words and amplifies their emotional thrust. His voice is accompanied by words that appear, both in and out of sync, on a black screen. The sound, reinforced by precise and sober visuals, elicits an immersive effect on an infra-individual level, an approach often used to arouse a collective resistive force. The artists developed this process to emphasize the relationship between the voice and the body in Fanon’s work, considering that he didn’t actually write his texts but dictated them to his companion, Josie Fanon, among others. This practice embodies an improvised writing of the body in movement. Fanon wanted his words to carry his lived experience and what it reveals of the intangible. Corps à corps conveys the breath of revolt that resides and survives, on a molecular level, in bodies engaged in a process of decolonialization.

Close-Combat, captures vidéos | video stills, 2016.

Photos : permission des artistes | courtesy of the artists

Relation is a movement; it both relates and relays. The practices of Marcassa, and Babari and Paillard exercise a poetics of relation that acts beneath the surface, thus complicating the components. In this sense, they are concerned less with empathy than with the sympathy of things11 11 - Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design (Rotterdam: V2_Publishing, 2011), 159 — 77. — Einfühlung — as an aesthetic experience arising from emotional communion, from “sympathy”: a communion based not on identification, as one might think, but on intuition. It is by this sympathy that one is “transported into the interior of an object in order to coincide with what there is unique and consequently inexpressible in it,” as Henri Bergson wrote.12 12 - Henri Bergson, The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. Mabelle L. Andison (New York: Dover Publications, 2007), 173. It is life as an adventure of bodies, following the principle of encounter rather than recognition.

Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft