Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

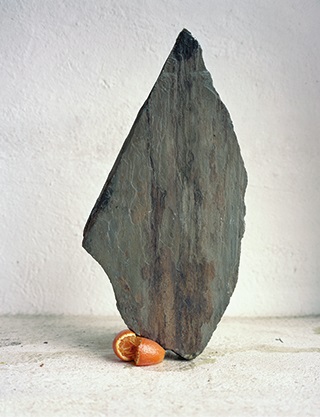

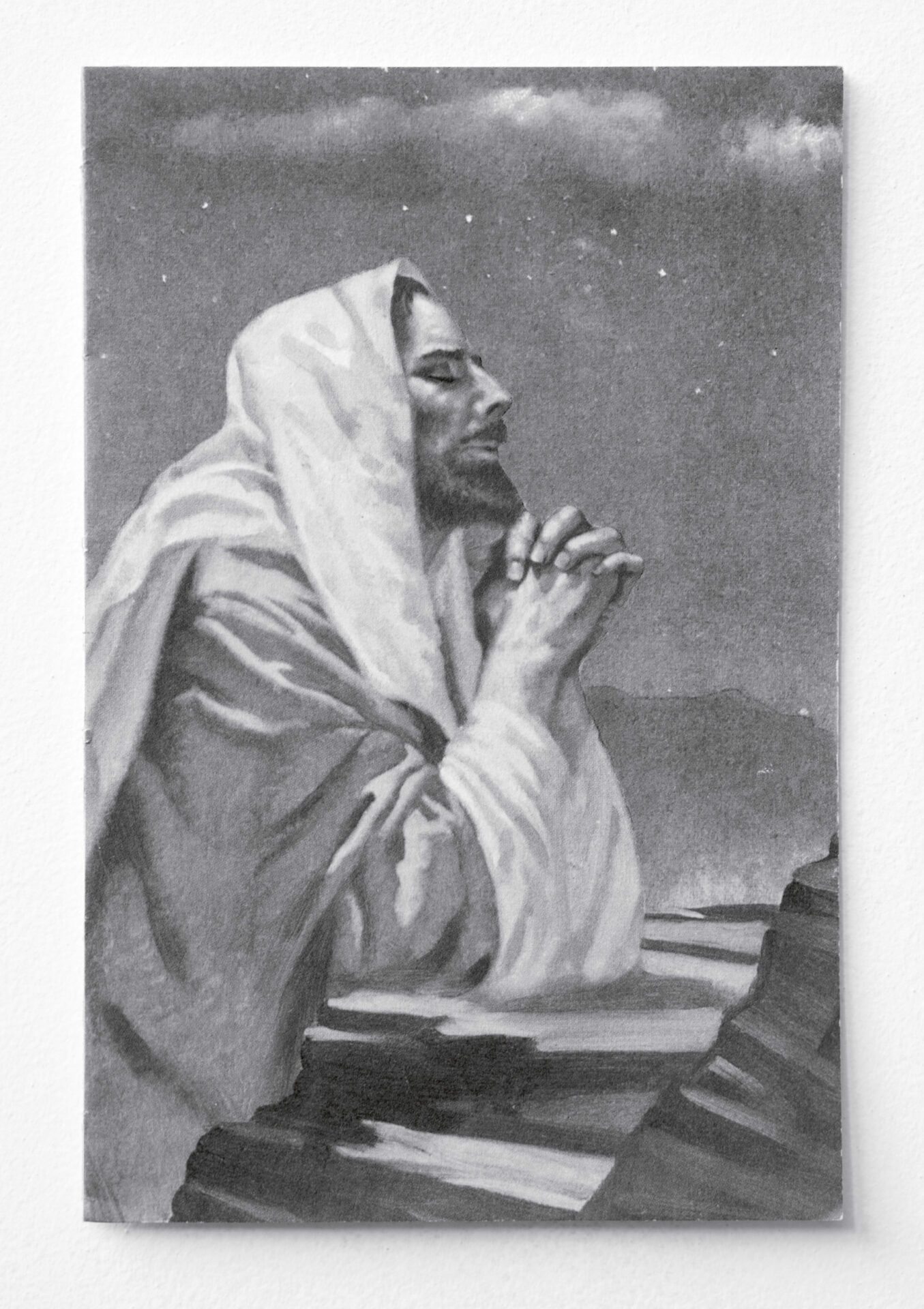

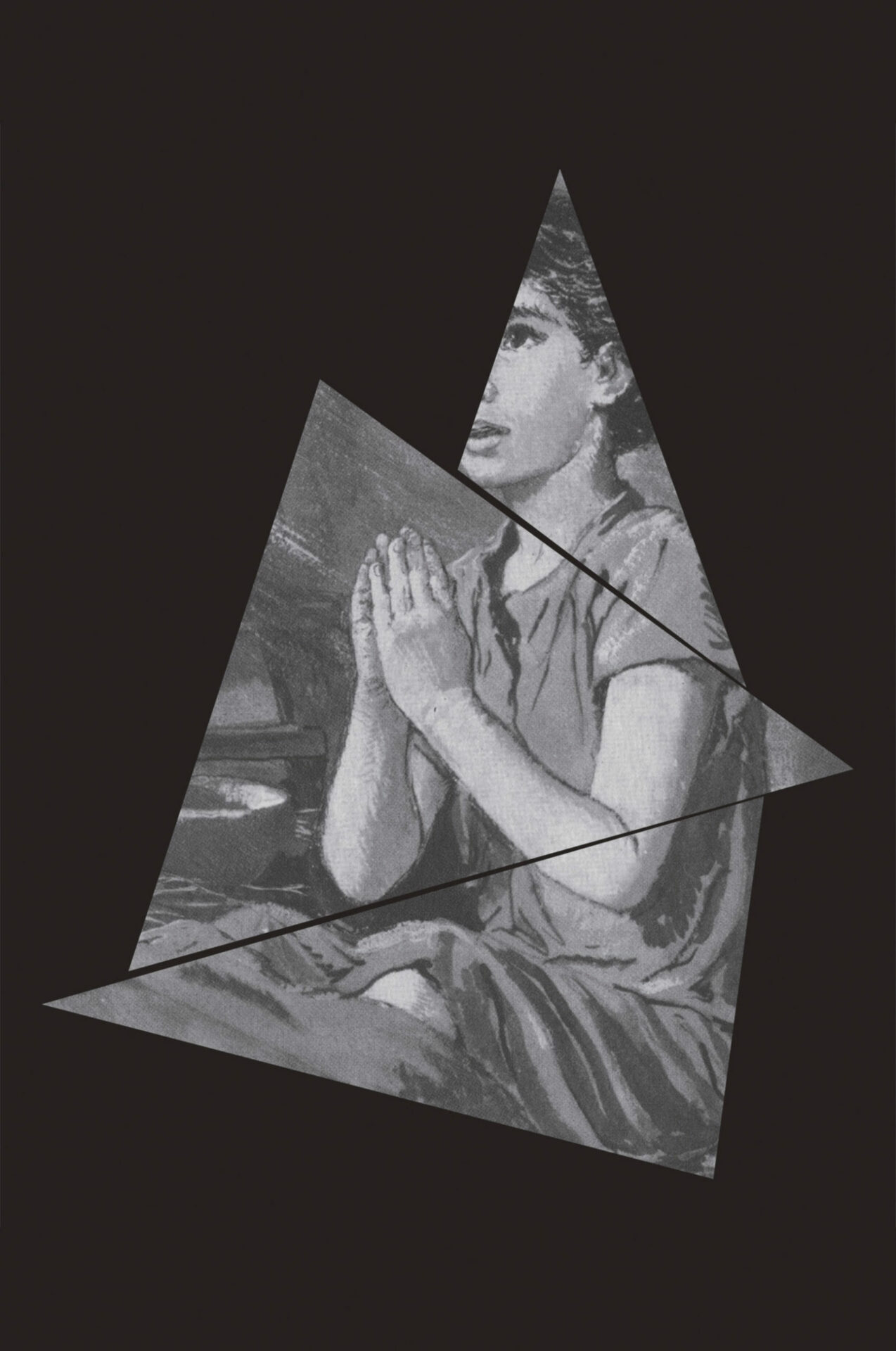

Darren Harvey-Regan’s new photographic suite, Metalepsis, presents a precise, yet open-ended group of small photographic images. Pared-down, formalist, geometric, very nearly black and white images depicting arrangements of surface textures (are they rocks? concrete? polystyrene?) in a nondescript, shallow space; two identical “bracket” images at either end of the series — meant to highlight the latter’s circularity — each consisting of a double image of a single orange appearing side by side on a plain background. On the left, both the orange and the background are the same uniform shade of orange; on the right, the entire image is black and white. In the centre of the series, there is just one more instance of saturated colour, in the form of an image of a sharply pointed stone squashing an orange in what appears to be a vaguely studio-like setting. Interspersed with these images are two paradoxical images of prayer: to the right of the central, squashed orange, what appears to be a black and white photograph of a kitschy postcard of Jesus, hands clasped, looking to the heavens; to its left, another praying figure (the young prophet Samuel) whose image has been cut into shards. Just three triangular chunks of the figure’s image have been placed against a rich black background.

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig. 9, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

This suite stages a dense thought process: threads and strains of almost-arguments seem to circle endlessly around an absence of a central “content.” This affective absence, however, at the heart of the work, feels highly specific, full of the feeling of emergent thought; it embodies the same sort of future-facing, but as of yet still silent fullness of a pensive face that is just about to speak. The suite proceeds meticulously through additions, negations, obfuscations, juxtapositions, and inflections of one image with another. Yet within this plurality of processes emerges an oft-reiterated concern. Without, I hope, placing too centralizing a claim on this concern (I would still rather say that the heart of this work can’t be said, and even more than this, that this sense — and concept — of the unspeakable is itself central to the logical/affective structure of the work), I want to argue that this suite performs a double procedure, according to which the mysteries of transcendence are staged as both a trope and a mode of enquiry. This enquiry proceeds largely though a methodical and multi-faceted examination of the historical conditions through which conceptions of abstraction have been linked to — or severed from — conceptions of transcendence.

One aspect of this suite of concerns, which several of the photographs perform (and which are also performed between various pairs of photographs the eye selects) is doubt as to whether the depicted qualities in a given photographic image are properties of the objects depicted or of the medium itself. Is the orange orange because of the pigments in its skin, or the idea of “orangeness” that has seeped from the orange into the image’s processing? Is a sudden darkening of the background due to a darkroom trick, or a nearly imperceptible change of materials? These images stage a sublimation of the representational concerns of the image towards transcendental interests in the dematerialization of imagery, and in the conditions of the medium itself as the very ground for the staging of that materiality. As such, they enact an epistemological doubt about the difference between the object of one’s perception and the perceptual grounds through which that object must come to be known. This is well-known art historical territory; the Greenbergs and McLuhans of the mid-twentieth century have produced (through argumentative description) a firmly entrenched portrait of a cultural and historical moment in which a concern with content, representation, and messages gave way to an urgent concern for examining the background, the medium, the conditions through which representation could come to be staged in the first place.

Yet for all this, the use of photography, here, as a medium for examining the genealogy of abstraction’s concerns ups their indexicality, their ostensible drive to have “content.” Indexicality — the ability to rhetorically point to an actual thing in the world that remains outside of, yet is metonymically linked to, representation — is a “native” concern of photography in much more pointed a way than, say, painting. As such, it is also, perhaps, photography’s red herring; these images’ indexical properties — their insistence on referring to an actual space that exists outside of the photograph — disintegrates under close inspection. Planes that seem to represent a swath of space from a distance, up close appear to present flat surface textures, perhaps of construction paper, MDF, or another mottled, pulp-based surface, that have been carefully placed (Thomas Demand-style but flatter and more formalistic) to give the illusion of three dimensionality. (Harvey-Regan’s images disperse their own indexicality, taking it through detours, pinging it in unexpected directions.) For all these images’ panache in exploring such complexities of mid-twentieth century attitudes toward abstraction, this in and of itself is only one strain of Metalepsis’ thought. For what, after all, are those puzzling images of prayer doing in the mix? These images prevent the series from becoming too pat in its handling of the above concerns; they open it out onto a much wider enquiry, tracing a broad historical change in the relations between abstraction and transcendence.

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig. 8, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig 4, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

At the turn of the twentieth century, abstraction, spirituality, and transcendence (both as concept and as embodied practice) seemed to go hand in hand. For Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich, abstract painting was a means though which to explore theosophy, to transcend and sublimate representational and quotidian concerns in order to arrive at a more general, philosophical enquiry into origins. This prevalent link between abstraction and transcendence persisted well into the 1950s; emblematic of this insistence is Barnett Newman’s work, in which interests in both the sublime and mythological/religious references are inextricably intertwined. Newman sought to reduce, to abstract a sense of encounter until it was merely a “zip,” a sense of felt particularity that emerges before words, before symbolization can catch it. The sense of emergence-before-words his zips aspired to was a gateway of sorts to the sublime dimension of experience.

Yet the emerging generation of postmodern artists of the 1960s identified, pronounced, and helped to produce a fundamental shift in the epistemic relation between concepts/practices of abstraction and those of transcendence. For them, abstraction, having become a normalized, and even hegemonic procedure in New York School painting, became simply repression. Martha Rosler was among the many artists of that generation who would come to view Greenberg and the bland, wallpaper-like canvases he touted to be fundamentally conservative, exclusionary, duplicitous. Their claim to “contentlessness” could only function as a tacit claim to privilege — a short-sighted, individualistic abandonment of the aesthetic tasks of citizenship, the latter of which, for many in Rosler’s generation, urgently required representation as both a mode of enquiry and a subject for analysis.

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig 10, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig 7, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

À ce transfert épistémique fondamental, les images de prière de Harvey-Regan répondent par un argument qui l’infléchit. Admettons (semblent-elles nous dire) que le lien qui unissait l’abstraction à la transcendance ait été rompu au cours du siècle dernier. Comment ce lien pourrait-il être réactivé, réénergisé – et que pourrait-on apprendre d’une telle réactivation ? Les images de prière – infusées d’une certaine distance ironique (au sens très particulier où l’entend Franco Bifo Berardi, non pas sardonique, cynique ni surchargée d’une référentialité par trop habile, mais plutôt comme ouverture possible entre l’image et la façon dont elle est lue1 1 - Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, Los Angeles, Semiotext(e), 2012, p. 159–166. – viennent en aide ici aux abstractions, en leur transfusant de ce contenu qui leur fut jadis transcendant, « natif ». Ce mot, « natif », au sens où je l’entends ici, s’apparente davantage à « nativité » qu’à « naturel » ; en effet, l’idée d’un lien originaire entre l’abstraction et la transcendance, lien formé dès la naissance de l’abstraction au début du 20e siècle, ne le rend pas nécessairement « naturel ». Elle le fait paraitre naturalisé, plutôt, en jouant pour lui le rôle d’un échafaudage mythologique, procédure idéologique inhérente selon laquelle la transcendance se rattache « nativement » à l’abstraction dès son point d’émergence. La religiosité, vue comme un contenu répressif – et comme une relation répressive au fait de représenter du contenu – par une grande partie de la génération postmoderne, bascule et devient la grande réprimée de la postmodernité. Dans quelles conditions le lien peut-il (et devrait-il) donc être ressuscité ? Prise comme un tout, la série photographique – une espèce de moteur alimenté par le couple abstraction-transcendance, concepts aux charges opposées et pourtant inextricablement liés – se trouve à la fois à réactiver l’appariement natif de ces concepts et à remettre en question les motivations mythologiques qui sous-tendent une telle réactivation. Elle s’abstient aussi, délibérément et nécessairement, de conclure à cet égard ; sa tâche consiste à étaler les circuits de son paradoxe et à baliser un espace vide de contenu au centre de ces pôles de réflexion en conflit. De ce point de vue, elle réalise vraisemblablement une relocalisation du concept de l’absence de contenu, une réorganisation du transcendantal contemporain sécularisé en tant qu’espace entre les pôles d’un paradoxe épistémique.

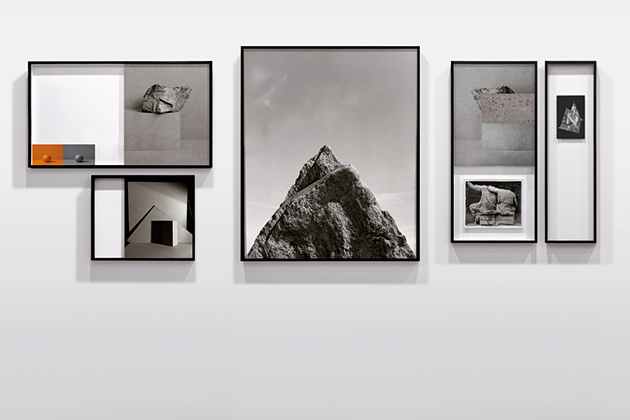

Metalepsis, 2014

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Metalepsis, détail | detail fig. 1 & 13, 2014.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

For me, there is one image in this series that has the final word, that invents its own modality of abstract-imagistic transcendental enquiry, or perhaps poses the series’ questions most urgently. The praying image of Samuel cut into triangular shards, linked up side by side on a black background, carries a small but potent hint of violence toward embodied materiality, enacted through geometry (it is an image whose geometry flagellates its own reverent subject). It hints at a history that would link abstraction not only to transcendence but also to iconoclasm. It enacts the disembodiment of an aim toward the heavens as a both a reverence for, and a violent aim to break away from, the powers of images and their indexical procedures. On its own, perhaps the image would not do this, but in its place in the series, given the specificity of the content stream it swims in, it retells the sublimation story by posing another problem with representing sublimation through images (against what ground can it be shown, given that the ground is always already infused with a faith in images?). The fractured Samuel speaks powerfully to the embodied experience of the discipline of transcendental experience arrived at through (among other things) intense questioning: an experience which is potent enough to shatter represented reality into shards, and yet at the same time hold those shards dear, protect them in an alien pasture of geometric, self-similar, abstractable space.

[Traduit de l’anglais par Sophie Chisogne]