The Social Constellation of the Stadium

Such suspension and mediation is also true of the experience of sport today, and increasingly so amidst waves of lockdown. The appeal for me was never simply the game itself, but the chaos of the crowd, the nostalgic soundscape of the audience, and the architecture that is so purposefully built. Emptied of these crowds, the stadium becomes a strange, hollow structure. Here I will reflect on ways in which the stadium is represented in contemporary art as a space that houses not the imagined communities that it is sometimes said to, but a fractured and fragmented crowd, a sort of social constellation that belies the myth of united spectatorship. Most communities are in a very real sense imagined, and this is not, as political scientist Benedict Anderson argues, a marker of inauthenticity: “Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined.”2 2 - Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London and New York: Verso, 2006), 6. It is the role of narratives, which construct personal and collective identities, and “meaning-creating experiences3 3 - Anderson, Imagined Communities, 204-05, 53.” that are key here, and although Anderson is considering the imagined community of the nation-state, the role of narratives and the creation of meaning are likewise instructive in considering the stadium’s imagined communities.

Stadium, 2020.

Photo : courtesy of the artist & Midway Contemporary Art

Commissioned by Midway Contemporary Art for a series of off-site works throughout Minneapolis in late 2020, Stadium draws on Marsalis’s experience visiting Dodger Stadium after-hours. He recalls that it was “the most surreal, but most boring, experience because nothing is happening” and that he was left waiting for an unrealized potential.4 4 - Alicia Eler, “Closed by pandemic, Minneapolis art center takes its shows on the road,” Star Tribune, November 12, 2020, accessible online. This experience appears to be meaningful not despite the absence of others but because of this absence, because of the sense of suspension experienced by Marsalis. This, in turn, presented a space for reflection. Marsalis’s Stadium can be seen as an anti-monument that serves as an “arena for reflection.”5 5 - Jasper Marsalis, Stadium (exhibition statement), Midway Contemporary Art, accessible online.

Located in southeast Minneapolis, the work sits on a site slated for development that local residents fear will be a form of greenwashed gentrification. In “The Convex (No Place Is or Ever Was Empty),” Alexandra Nicome traces histories of redlining and racist exclusion in the region, which become spectres haunting her experience of the work. About the site, she writes, “Stadium is located in a new development that is promised to be a climate-friendly, mixed-use community. With any new construction, I can’t help but think about gentrification — and no matter the number of affordable units, I anticipate certain loss and displacement. It is important to highlight gentrification in the Twin Cities today, and to acknowledge that inequitable access to affordable and safe housing in Minneapolis, especially for Black folks, draws from a long history.”6 6 - Nicome, loc. cit.

Stadium, 2020.

Photo : courtesy of the artist & Midway Contemporary Art

Marsalis’s Stadium serves as an opening, allowing a refocusing of attention on the structural violence that underpins this public space. Although a public assembly is not the cohesive community that it may claim to be, the projection of a unified public will in turn dictate the parameters of the conversation. As Black studies scholar, writer, and artist Jackie Wang reminds us, the “engineering and management of urban space also demarcates the limits of our political imagination by determining which narratives and experiences are even thinkable.”7 7 - Jackie Wang, Carceral Capitalism(South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2018), 273. This constructed singularity and the flattening of social stratification can be deeply misleading; it is the circularity and decentred nature of Marsalis’s work that makes it so intriguing, as does the critical reflection that it invites.

Crowds and Constellations

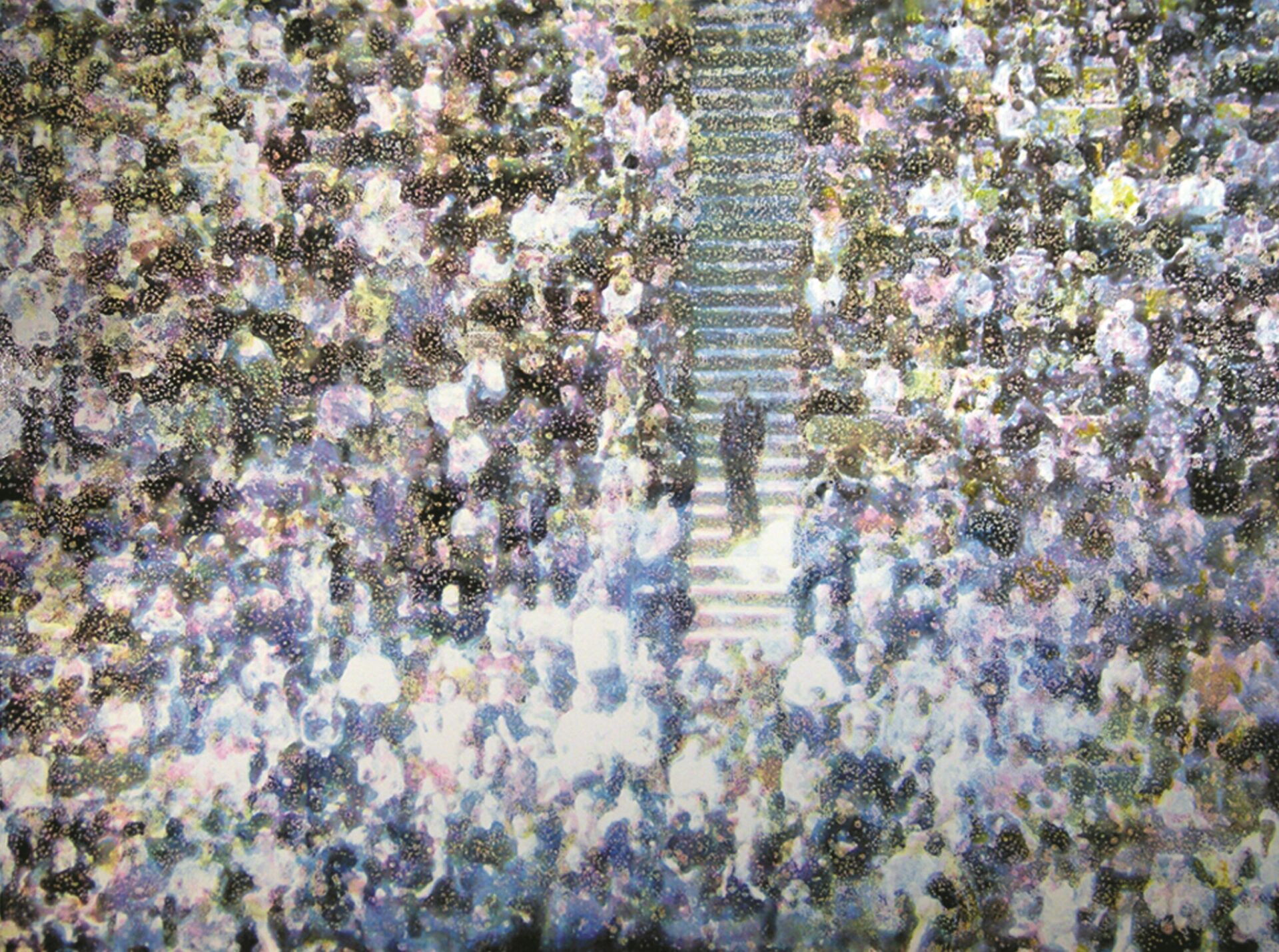

Although Stephen Andrews’s depictions of stadiums are similarly decentred, there is a marked difference given the mass of bodies that crowd the canvas in his paintings. The open space of works like Marsalis’s is abandoned in favour of an accumulation of often-distorted spectators, each composed of multiple smaller marks from which bodies are built, with some marks being disconnected and others blurring into one another. Andrews has referred to his work as being, in a sense, “constellated,” and although this is a clear reference to his depictions of stars, it is also an apt description of his approach to mark making, in which figures are often composed of discrete marks and accumulated layers of paint.

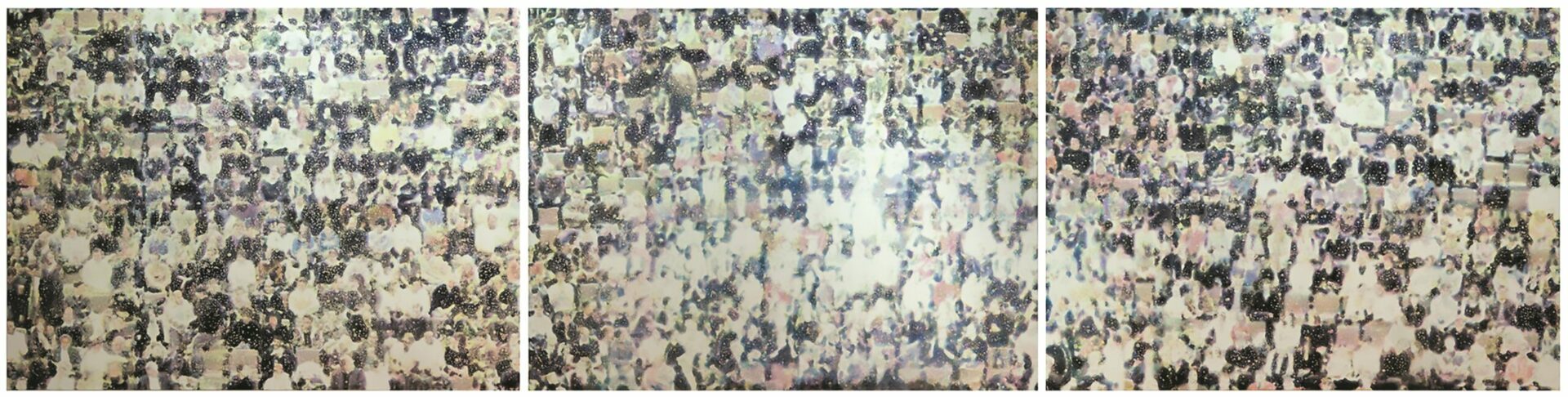

Andrews’s Stadium (2009) and triptych The View From Here (2009) depict spectators watching an unknown event; some stay seated, others talk with neighbours, and still others come and go from their seats. The large canvases of The View From Here have an immersive quality that is heightened as the twenty-four-foot-wide triptych fills the viewer’s field of vision. This work was a massive study for a commission in downtown Toronto, in which Andrews sought to represent a specific imagined community. He states that he was “looking for a place where Toronto performs the myth of itself, as a multicultural place, most convincingly … And that happens to be at Raptors games.”8 8 - Murray Whyte, “Stephen Andrews: Far away, up close,” Toronto Star, April 22, 2015, accessible online.

Compared to the eerie emptiness of Marsalis’s stadium, Andrews’s has a familiar fullness. As the athletes perform, so, too, does the audience. Spectatorship is, after all, never truly passive. The spectator is tasked with making meaning, and as Majid Yar argues, the spectator’s role is “that of rescuing past meanings and actions from the oblivion and forgetting of history.”9 9 - Majid Yar, “From actor to spectator: Hannah Arendt’s ‘two theories’ of political judgment,” Philosophy & Social Criticism, 26, no. 2 (2000): 18. The presence of the crowd animates Andrews’s stadium, a crowd that itself is evidently animated.

Stadium, 182,9 × 243,8 cm, 2009.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Yar develops his theory of the spectator from Hannah Arendt’s writing on action, judgment, and participation in public life. In Arendt’s view, appearing to others allows for one’s thoughts and actions to achieve a reality that they could not had they remained private, for “even the greatest forces of intimate life … lead an uncertain, shadowy kind of existence unless and until they are transformed, de-privatized and deindividualized.10 10 - Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 50. If The role of spectators is thus elevated, in that they can give meaning to experiences, which might in turn support the constitution of Anderson’s imagined community. To Arendt, the “public realm, as the common world, gathers us together,” and appearing is crucial, as “without a space of appearance … neither the reality of one’s self, of one’s own identity, nor the reality of the surrounding world can be established beyond doubt.”11 11 - Arendt, The Human Condition, 52. 208.

The View From Here, 182,9 × 731,5 cm, 2009.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Andrews’s stadium-goers are likewise active players in the tableau, and The View From Here is given new meaning when we consider the profound significance that seeing and being seen can have. By gathering, the audience is certainly animating and organizing the space, and the public space is itself gathering them together. Yet the danger of the imagined community is that it forecloses a space of difference, inviting a community to perform the myth of itself. Crowds are, after all, social constellations, diverging and converging with a rhythm of their own.

1/1, installation view, Artlab Gallery, Western University, London, Ontario, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Bodies in Bleachers

Against Marsalis’s and Andrews’s massive stadiums, Michelle Bunton’s more intimate participatory installation 1/1(2016), which features bleachers facing a video work, foregrounds the auditory dimension of spectatorship. Visitors are invited to sit on the custom bleachers, which are outfitted with a mechanism that plays pure bass vibrations, invoking the cheers of a phantom crowd. It is an embodied experience that intensifies after contact is made with the structure, which resonates with the sounds of this dematerialized crowd. The bleachers face a monitor depicting a sequence of pixels, drawn from an iconic sports image. Slowly cycling through more than three thousand individual pixels, the video, which never reveals the full image, lasts the length of a regulation basketball game. Whereas Andrews’s accumulation of marks culminates in a recognizable image, here the viewer is left wanting. As in Marsalis’s Stadium, there is an unfulfilled anticipation, with the continued absence of a discernible subject or a point to focus on. Perhaps more accurately, the experience is so profoundly distilled that all the viewer is left with is a series of decontextualized and abstracted points.

In a recent conversation that I had with Bunton about the work, they discussed the labour-intensive process behind extracting the pixels, which required a kind of video-editing athleticism. Rather than develop a program that would automate the process, they chose to manually edit the massive sequence of pixels, pushing their body and undertaking a discipline that reminded them of their previous involvement in organized sport. The result was an archive that disrupts its own function. As Bunton stated, the “creation of archives in an attempt to preserve a subject can strip a subject of its subjectivity.”12 12 - Author’s interview with Michelle Bunton, February 20, 2021. The video serves as a futile stand-in, a poor image deconstructed to become a poor substitute. Each pixel on the monitor changes with the sound of a player pivoting, that familiar squeak of the sneaker on the court gradually developing a metronomic quality. The viewer’s inability to read a coherent image pushes up against the sense of order and control that the metronome invokes, and Bunton is interested in how the act of mediation fails to resolve itself in the way it often promises to. There are limitations to the legibility of the rhythmic chants as well. Some of the chants are regional and may not be recognized by all visitors. As with any ordered assembly, they fall short of the universality that they are often assigned. 1/1 is about the sights and sounds of the imagined community, isolated to pure bass and a sequence of pixels, via a mediation that is rather upfront about its own inefficacy.

Amsterdam, Arena III, 2003. © Andreas Gursky / SOCAN (2021)

Photo : courtesy of Sprüth Magers

Stadiums Reconstructed

The word “stadium” originally referred to a specific distance equalling the length of six hundred human feet. In its earliest iterations in ancient Greece, the only purpose of the space was for spectators to watch as athletes sprinted from one end to the other. “Stadium” is derived from the Greek stadios, meaning firm or fixed, and invokes a standard, set length, even though it is a measurement derived from the body. This tension between uniformity and variance pervades these works, and the force of the body upon these structures is clear. It is likely the absence of this force that left Marsalis feeling uneasy or empty when he visited Dodger Stadium. The vacant space ceased to be a space of appearance, and, as Arendt reminds us, if you remove the vibrancy of public participation you are left with a shadowy kind of existence, not unlike Bunton’s phantom crowd.

Andreas Gursky’s large-scale photographs similarly grapple with animation and appearance. Although many of his works focusing on stadiums, such as Sha Tin (1994) and Dortmund (2009), resonate with Andrews’ depictions of unbounded crowds, in Amsterdam, Arena III (2003) only the arena floor is seen within the image frame, as we witness its remaking. The majority of the ground is covered by a vast expanse of evenly spread sand, as rows of grass are being laid by workers entering the frame from the right side of the image. This measured, organized maintenance harkens back to the stadium’s origins as a standard distance, and the presence of the workers’ bodies invokes the human scale that this history points to. It was not the imperial foot that was employed, but the actual feet of those measuring it. The workers remind us that although these spaces are animated and, in a sense, reconstructed through our participation, so too are they constructed and reconstructed through the unseen labour that provides for their material existence. Stadiums operate on a human scale and on multiple registers.

Nicome’s discussion of Marsalis’s Stadium resonates with this emphasis on recognition; although the presence of bodies must be accounted for, we must also remain aware of those who are displaced and dispossessed, both now and in the past. The imagined community and its many myths offers convenient narratives, but it obscures a far more complex and stratified reality. As the anti-monument of the stadium encircles the event, how do those in attendance orbit around each other, and what fractured collectivities and social constellations are formed in the process? Even though the viewer can enter and animate Marsalis’s and Bunton’s installations, the works are never fully realized. There is no anticipation in the final moments of the game, no cathartic release of the last buzzer-beater. Gursky’s reconstructed stadium and Andrews’s packed bleachers are similarly unfolding, though there is a suspension here too. The quiet, repetitive labour seen in Gursky’s Amsterdam, Arena III contrasts with Andrews’s animated crowd, but both serve to remind us of the way in which these spaces gather us together. These works all reflect on the public space of the stadium, inviting deeper reflection on who participates, what that participation may look or sound like, and on what communities are imagined in the process.