Rotterdam, June 2, 2012: For the past few days, observed attentively by puzzled onlookers, a whale has been swimming around the huge maze of the harbour. What is it doing here? Is it off course, frightened, amused? No. It is enthralled, for in an old submarine hangar, Sarkis has installed a work that is emblematic of his entire oeuvre: Ballads (2012), the core of which is John Cage’s Litany for the Whale. 1 1 - Ballads was at Submarine Wharf from June 2 to September 30, 2012. At the same time, another work by Sarkis consisting of ninety-six watercolours interpreting Cage’s Ryoanji was on display at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

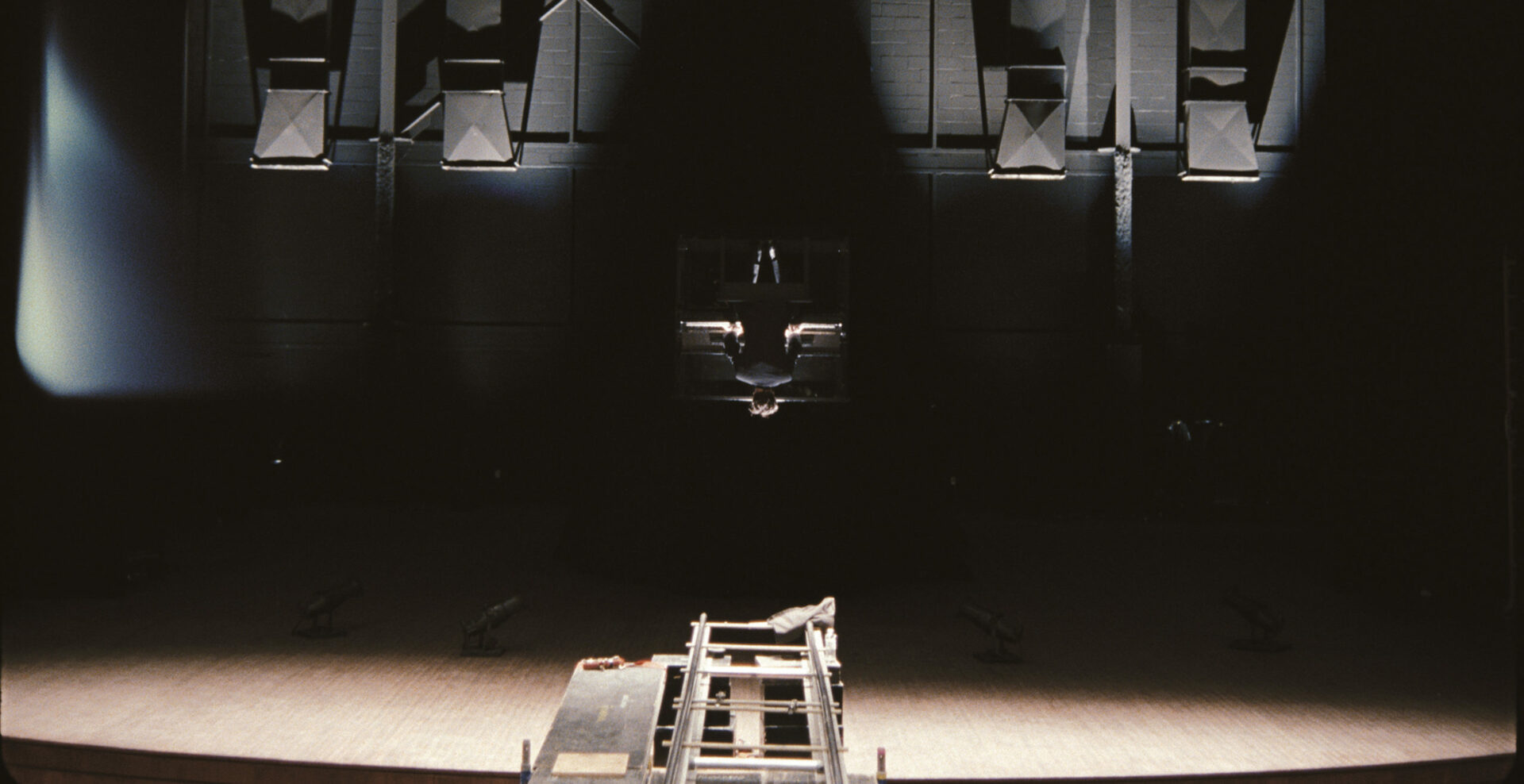

This legendary music, dating from 1980, was not rendered according to the score’s instructions, which call for a repeated recitation followed by thirty-two responses sung in alternation by two equal voices. Instead, Sarkis had it played by a carillonneur on a complex keyboard that rang a carillon of forty-three bronze bells set in a colossal circular wooden structure rising eighteen metres above the ground.

vue d’installation | installation view, Submarine Wharf, Rotterdam, 2012.

© Sarkis / SODRAC (2014)

Photo : Wayne Cullen

permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The installation — its gothic upward thrust and sacred dimension inspired by Pieter Saenredam’s seventeenth-century paintings of churches — was part of a project undertaken jointly by the Port of Rotterdam and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen to revitalize Submarine Wharf.2 2 - Submarine Wharf, built in 1937, is comparable in size to the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, London. Transformed by the artist into a space of contemplation, this industrial building resounded with music to produce a kind of respiration that we might well believe spread into the depths of the sea around the city. Sarkis felt that the presence of a wandering whale was no mere coincidence.3 3 - Sarkis in conversation with the author, Paris, September 19, 2012. It carried with it the spirit of John Cage, while Ballads, a work in progress when the whale arrived, bore Cage’s aural signature. Sarkis’s creative activity brought about not only the unexpected meeting of whales and submarines, water and air, but also of the darkness of the sea’s depths and the light of the hangar’s windows, which the artist arrayed with colour, like stained glass. Many were the interconnections established by the artist between past and present, and between the war, which left its mark on this city, and a new harmony involving the visual arts and music.

Il y aurait une multitude d’autres aspects de cette œuvre fabuleuse à révéler, entre autres le fait qu’elle incarne la dimension mémorielle de la souffrance et la tâche nécessaire de créer de l’harmonie. Le travail de Sarkis est intensément porté par la musique de grands compositeurs et interprètes tels que Jean-Sébastien Bach, John Cage, Dimitri Yanov-Yanovsky, Giya Kancheli et Morton Feldman4 4 - Voir Louise Déry, Sarkis, 2600 ans après 10 minutes 44 secondes, Montréal, Galerie de l’UQAM, 2004, 148 p.. Dès que j’ai reçu l’invitation de essepour ce numéro du trentième anniversaire, j’ai pensé aux œuvres de Sarkis, et j’ai souhaité considérer le phénomène si fertile de ces nombreuses pratiques artistiques investies par la musique. Il s’agit selon moi d’une tendance puissante dans la pratique des arts visuels des dernières années.

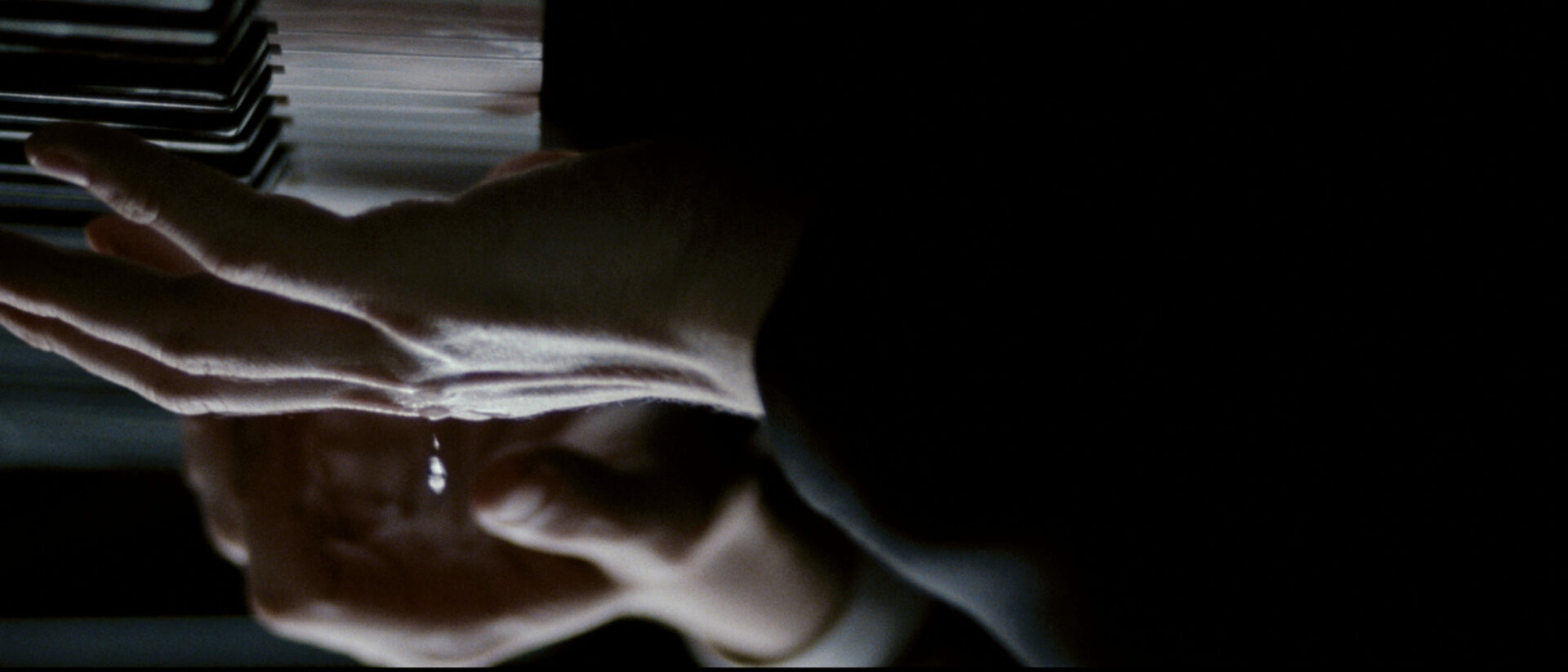

vue d’installation | installation view, Galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal, 2009.

Photo : L.-P. Côté, © Michael Snow

permission de | courtesy of Galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal

A host of other aspects of this fabulous work merit discussion, among them the fact that it embodied the memorial dimension of suffering and the effort required to create harmony. Sarkis’s production is permeated by the music of great performers and composers, such as Johann Sebastian Bach, John Cage, Dimitri Yanov-Yanovsky, Giya Kancheli, and Morton Feldman. When asked to contribute to this thirtieth-anniversary issue of esse, I immediately thought of Sarkis and wanted to consider the fertile phenomenon of the many current art practices pervaded by music. I believe this has become a vital trend in the visual arts over the past few years.

It is not really a recent phenomenon. The joining of music and the visual arts has nearly always been common. Especially since the early twentieth century, many artists have experimented in this area, and a myriad of thinkers, such as philosopher Theodor Adorno,5 5 - See Theodor W. Adorno, Über einige Relationen zwischen Musik und Malerei. Die Kunst und die Künste (Berlin: Akademie der Künste, 1967). have taken a keen interest in the encounter of the arts. As a result, an unmistakable resonance hovers between the characteristics specific to each, their boundaries fraying as they rub against one another. The visual arts and music have both undergone an enriching shift that ensues from their cross-fertilization and invokes listening and looking in a different way. In hearing and vision, in what has to do with understanding and perception (or comprehension and intelligibility), something springs forth from this impressive convergence explored by artists such as Sarkis, Michael Snow, Stan Douglas, the duo Allora and Calzadilla, and Patrick Bernatchez, to name only a few.6 6 - And, of course, Anri Sala, Philippe Parreno, Ragnar Kjartansson, and others. They have all created major works that incorporate music, which they regard neither as a language for translating or interpreting the visual, nor as the transposition of possible formal, structural, and rhythmic equivalences. They approach the question by way of different paths, but — and this strikes me as particularly significant — they all treat music as a malleable substance, a sculptural material modelled in a performative context, an anthropological material that can absorb the imprint of the visual and stimulate thought.

The most musically inclined of these artists is incontestably Michael Snow, whose visual art practice merges with the music that he improvises, composes, and “sculpts.” A blues and jazz pianist, brilliant improviser, and prolific composer, he promotes experimental music produced in a context of free and spontaneous improvisation. As he wrote in 1967, “I am not a professional. My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor, sculpture by a filmmaker, films by a musician, music by a sculptor . . . sometimes they all work together. Also, many of my paintings have been done by a painter, sculpture by a sculptor, films by a filmmaker, music by a musician.”7 7 - Michael Snow in Statements/18 Canadian Artists, exhibition catalogue (Regina: Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1967), unpaginated; reprinted in The Collected Writings of Michael Snow (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1994), 26. His wish is to orchestrate mediums all of which have specific traits, and to develop variations on themes that fall within a continuous movement in his approach as a whole.

Snow’s Piano Sculpture (2009), a pivotal work, consists of four videos projected on the wall showing the artist’s hands as he improvises at the piano — four solos meant to be presented simultaneously. The projections seem identical but they are not, any more than is the music that goes along with them — a set of subtle piano variations featuring the glissandi and tone clusters characteristic of the artist’s aural experiments. It is, as Snow puts it, a “handmade” work,8 8 - See Louise Déry, Solo Snow: Œuvres de/Works of Michael Snow (Tourcoing: Le Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains; Montreal: Galerie de l’UQAM, 2011), 60. sculpted in the musical material itself, exploiting the possibilities of the instrument and the movement of the hands over the keys to produce a quartet of high-energy sounds. By including loudspeakers in the image of each projection, the artist creates a kind of bas-relief that induces us to stop and take in the unique musical identity of each element. In so doing, we move around the sculpture and experience its three-dimensional reality as both an audible shape and an aural sight. Piano Sculpture acts doubly on us: it attracts both ear and eye; its fourfold projection both resonates and illustrates.

captures vidéo | videostills, 2014.

Photos : permission de | courtesy of the artist

& David Zwirner, New York

In his most recent film, Luanda-Kinshasa (2013), Stan Douglas masterfully deploys the poetical and political force of jazz by revisiting the history of a legendary midtown Manhattan recording studio. Nicknamed “the Church,” Columbia’s studio on 30th Street (no longer standing) was where countless musicians recorded famous albums over a period of three decades, including Glenn Gould (Bach: The Goldberg Variations, 1955), Miles Davis (Kind of Blue, 1959), Vladimir Horowitz (Complete Masterworks Recordings, 1962 – 73), Bob Dylan (Highway 61 Revisited, 1965), and Pink Floyd (The Wall, 1979). Re-creating the studio in a deconsecrated church in Brooklyn, Douglas stages a fictional jam session in the spirit of the 1970s. A dozen professional musicians improvise on sax, trumpet, drums, and guitar to paint a rich musical fresco that combines powerfully magnetic ethnic and stylistic influences.

The musicians concentrate on their work in a setting that seems frozen in time, in which friends, journalists, and sound technicians bustle or linger quite naturally. The visual representation focuses on the musical experience itself and lasts more than six hours. The film that we watch and that makes us witnesses to the performance is at once an improvisation that produces musical material, a recording session that establishes the enduring character of the work, a method of sampling and editing (musical motifs are reinitialized and fragments of the session are looped), and documentation ensuring the archival value of the performance.

Photo : David Jacques, Galerie de l’UQAM

permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Photos : © Patrick Bernatchez

permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Douglas’s power of evocation is embodied in the smallest details, with indications of the period such as posters and newspapers, cigarette and coffee brands, the musicians’ clothes, and various props that conjure up a vision of the Vietnam War era. These visual elements are woven into the musical fabric like a counterpoint. They transfer the meaning from the external world to the shared intimacy of music. The title, Luanda-Kinshasa, signals the film’s affiliation with the African origin of jazz. Improvisation as a means of giving birth and life to musical material is its basis; it guarantees freedom. The artist openly acknowledges this work’s debt to Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil (1968), in which the Rolling Stones record a song with that title for their album Beggars Banquet. Godard shows the rock group rehearsing and recording take after take of a song that would become emblematic, alternating with scenes that convey the mood of the times and reinforce the song’s revolutionary, symbolic, and satanic dimension.

Rooted in conceptual art and open to politics and subversion, the approach of Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla examines the role of music in social organizations and analyzes its perceptible dimension in the relationship between human beings and the living world. The artists probe links between militarism and music, for example, in a work that diverts the use of bagpipes — the only musical instrument, as they like to recall, that is considered a weapon of war.9 9 - There’s More than One Way to Skin a Sheep, 2007, video with soundtrack, 6:40. Bagpipes were banned as a weapon in Scotland after the Battle of Culloden in 1746. In their films of an anthropological bent, visual process and musical material are subjected to concepts that grow out of painstaking historical and scientific research. For the 2012 Festival d’Automne in Paris, they explored the collection of the National Museum of Natural History and came upon the unusual case of Hans and Parkie, two elephants confiscated as war trophies and given to the museum in 1798. That year, some musicians organized a concert in the museum during which an experiment was conducted to investigate the effect of music on animals. The film Apotomē (2013) is based on this experiment, which Allora and Calzadilla have in a way re-enacted by putting together a concert with a repertoire from that time.10 10 - Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride (1779), for example. They asked Tim Storms, who has the lowest-pitched voice in the world, to sing these pieces in the presence of Hans’s and Parkie’s skeletons, which are housed at the museum. Watching the film is quite disturbing. The singer’s unusual range, reaching eight octaves below the lowest G on the piano, defies human hearing, which cannot detect such low frequencies — only animals the size of elephants can. Listening to Apotomē dislodges the order of our perceptions and makes us realize how our experience of sonorous harmonies is subordinate to biological and cultural givens.

vue d’exposition | exhibition view, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, 2013.

Photo : © Marc Domage

permission de | courtesy of the artists & Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

captures vidéo | videostills, 2013.

Photos : permission de | courtesy of the artists

& Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

Like a number of other artists, Allora and Calzadilla alter the form and function of musical instruments and reserve an important role for performativity. For the duo’s Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on “Ode to Joy” for a Prepared Piano (2008), a circular hole was cut in the soundboard of a grand piano, through which the player slips to play Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” from behind the keyboard. In the music-based series Lost in Time, Patrick Bernatchez, another heir of John Cage, also uses a prepared piano to produce an object for performance purposes: Goldberg Experienced Ghosts Chorus (ongoing since 2010). As a functional sculpture, the piano has undergone (and is destined still to undergo) physical alterations during the recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations in Berlin by the New York pianist David Kaplan. For the vinyl recording of this sound work, Goldberg Experienced, 01 Berlin Session (2010 – 11), Bernatchez prepared the instrument thirty different ways, corresponding to the number of variations composed by Bach. Each preparation produced a sonority eroded by the contrivances placed on the instrument’s keyboard and soundboard. Unhinged, dislocated, thrown out of whack, the music creates a sound-space that sets up an intriguing potential for listening through still-recognizable fragments.

The film 180° (2011) illustrates the extent of the liberties that Bernatchez takes in exploring the malleability of music. In the ten-minute short, filmed in a concert hall in Montreal, David Kaplan performs Guillaume Lekeu’s Piano Sonata. The score, each page of which has been rewritten backwards, together with the pianist and his instrument, suspended upside down above the stage, reveal an unaccustomed facet of the music, a sort of underside made manifest by the aural and visual incongruity of the altered sonata and the way the pianist is harnessed. The strange dissonance of the reversed music is echoed by the equally strange position of the pianist, who must strike the piano keys against the force of gravity, as the camera shows in a dizzyingly inverted image. And there we are, transported to the concert hall, riveted by an uncustomary experience of both space and listening. With the same Lekeu sonata, Bernatchez also made the recording Piano orbital (2011), which includes four versions of the work: a performance of the original plus three variations, with the score rotated at an angle of 90, 180, and 270 degrees, respectively.11 11 - See Mélanie Boucher, Patrick Bernatchez: Lost in Time (Montreal: Galerie de l’UQAM, 2012).

A process of transitivity is afoot with Bernatchez, as well as Sarkis, Snow, Douglas, and Allora and Calzadilla, all presented here as artists who explore the transitional space between the visual and the musical. This observation seems to suggest that time is a key to what we might also view as an effect of reversibility. In bringing acoustic and visual phenomena into contact, what comes into play in duration (listening) is heightened by what is revealed in the instant (looking). Visual form and aural echo produce a resonance that creates new tension and awakens new attention.

[Translated from the French by Donald Pistolesi]