What we would now call curating, in effect this organizing of displays and publics, had constitutive effects on its subjects and objects alike.

– Simon Sheikh1 1 - Simon Sheikh, “Constitutive Effects: The Techniques of the Curator” in Curating Subjects, ed. Paul O’Neill (Amsterdam: De Appel, 2007), 175.

Little has been discussed concerning the curation of contemporary autobiographical art and the particular set of responsibilities that often accompany it. The word “autobiography” is an amalgamation derived from the Greek “auto” meaning self, “bio” meaning life, and “graph” meaning to write; since the 1960s it has become somewhat of a discursive battlefield for academics and thus continues to elude concrete definition. However, one of the most cited examples is that proposed by French literary theorist Philippe Lejeune, who suggests, “[ce] defines autobiography for the one who is reading is above all a contract of identity that is sealed by the proper name.”2 2 - Philippe Lejeune, Le pacte autobiographique, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1996 [1975], p. 33.Autobiographical art, as I understand it, is a mode of representation whereby an artwork’s subject matter or formal appearance is sourced from events or happenings in the artist’s lived experience and personal history. Here, the artist translates (or captures) fragments from the ephemera and storied conditions of their own vernacular life into the stuff of aesthetics. It represents an altogether distinct category of the visual in that it implicates the curation of lives-as-art rather than the curation of art-objects. “But,” sceptics ask, “isn’t all art autobiographical?” No, at least I don’t think so, in the same way that not every song is a ballad. To this end, much of the work of Bas Jan Ader, Nan Goldin, AA Bronson, Meryl McMaster, and Awol Erizku provide compelling precedents through photography, sculptural objects, and video, though this list is by no means comprehensive. Taking various patterns and appearances, these disclosures of the self played, and still play, an integral role in the constitution of the artist’s identity and the curator’s duty in articulating it.

Since the late 1950s personal video recorders have aided autobiographical artists such as Jack Chambers and Lisa Steele to cut down on the cost of production and presentation, allowing them to experiment with their own bodies (and autobiographies) as subject matter.3 3 - See (forthcoming) Matthew Ryan Smith, “Relational Manoeuvres in Contemporary Autobiographical Art,” in Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly 38, 1 (2015) For Chambers it was the fugitive moments with his immediate family in Hart of London, for Steele the physical injuries dotting her body in Birthday Suit with Scars and Defects. Recently, cultural critics such as Hal Niedzviecki argue that we, as a society, have entered into a capricious age of perpetual over-sharing; we have learned to zealously watch other people (and vice versa). Ultimately, as this and other literature make clear, our degree of consuming the lives of other people is unparalleled;4 4 - For more on how we, as a “peep culture” society, consume the lives of others see Hal Niedzviecki, The Peep Diaries: How We’re Learning to Love Watching Ourselves and Our Neighbours (San Francisco: City Lights Book, 2009). and, consequently, much of this is the result of a paradigmatic shift in the 1990s when reality television, tabloid magazines, talk radio, the cult of celebrity, and, of course, the Internet became quotidian apparatuses of the social. As these and other vehicles of self-expression trickled into the visual sphere, artists soon began to echo this au courant “culture of confession,” which produced a deluge of self-reflexive artworks, most famously those of the Young British Artists such as Richard Billingham and Tracey Emin. For some, Billingham’s photographic opus Ray’s a Laugh, taking its name from a popular BBC television series, stands as an uncompromising and atypical family photo album that captures his father’s alcoholism, his brother’s apathy, and his parent’s volatile relationship. Similarly, Emin’s My Bed, exhibited at Tate Modern in 1999, was a revelation. My Bed was met with hesitation from both the public and the art world, neither of which could fathom how or why her personal belongings and the daily detritus of her life could pass as art: here was a Duchampian epiphany. Emin and Billingham’s work represented the deterioration of the private realm and therefore anticipated the fracturing of identities in the twenty-first century. It also signalled an unprecedented shift in art criticism whereby audiences and critics alike circulated judgements based on the artist’s personal life rather than on the aesthetic merit of their work.

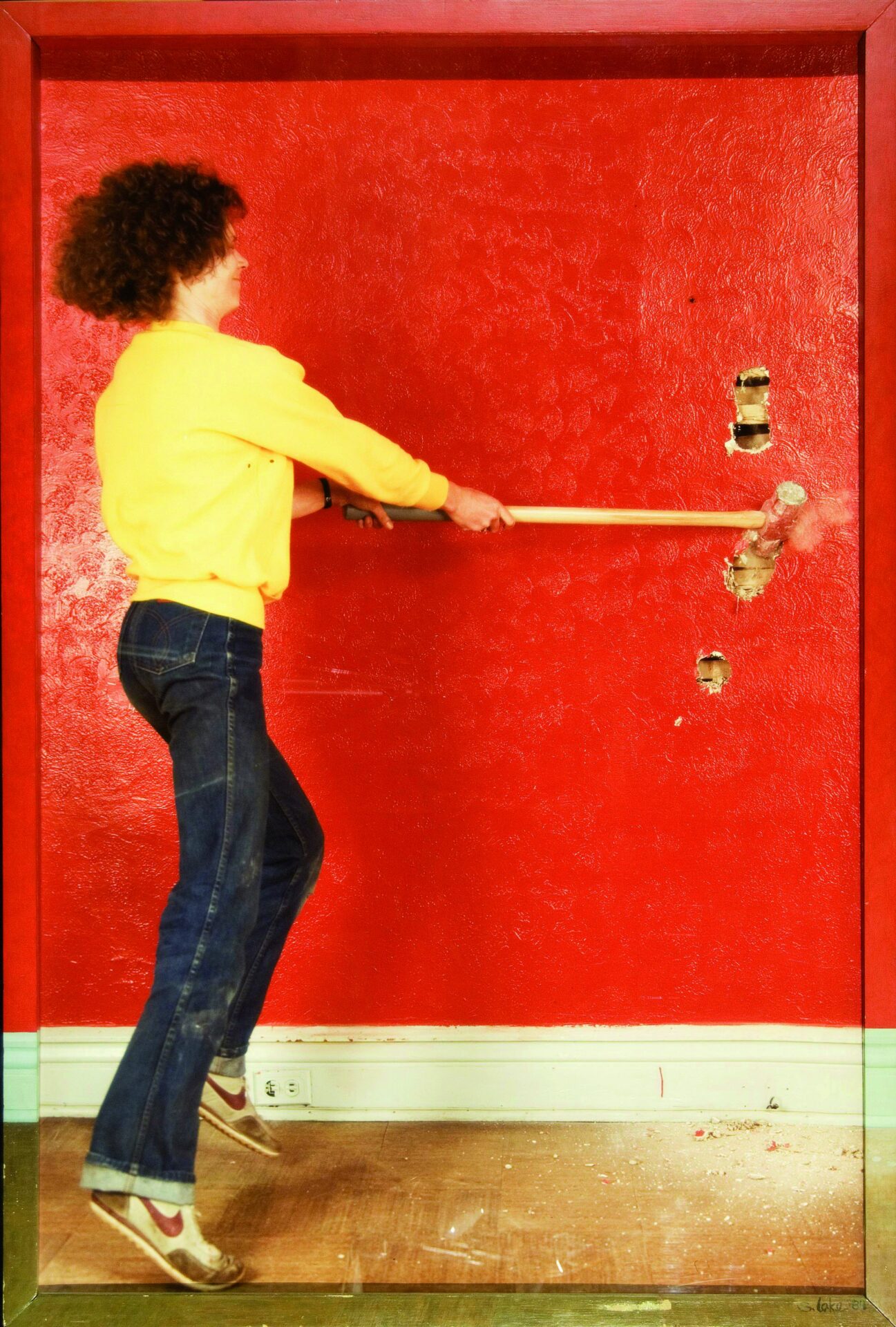

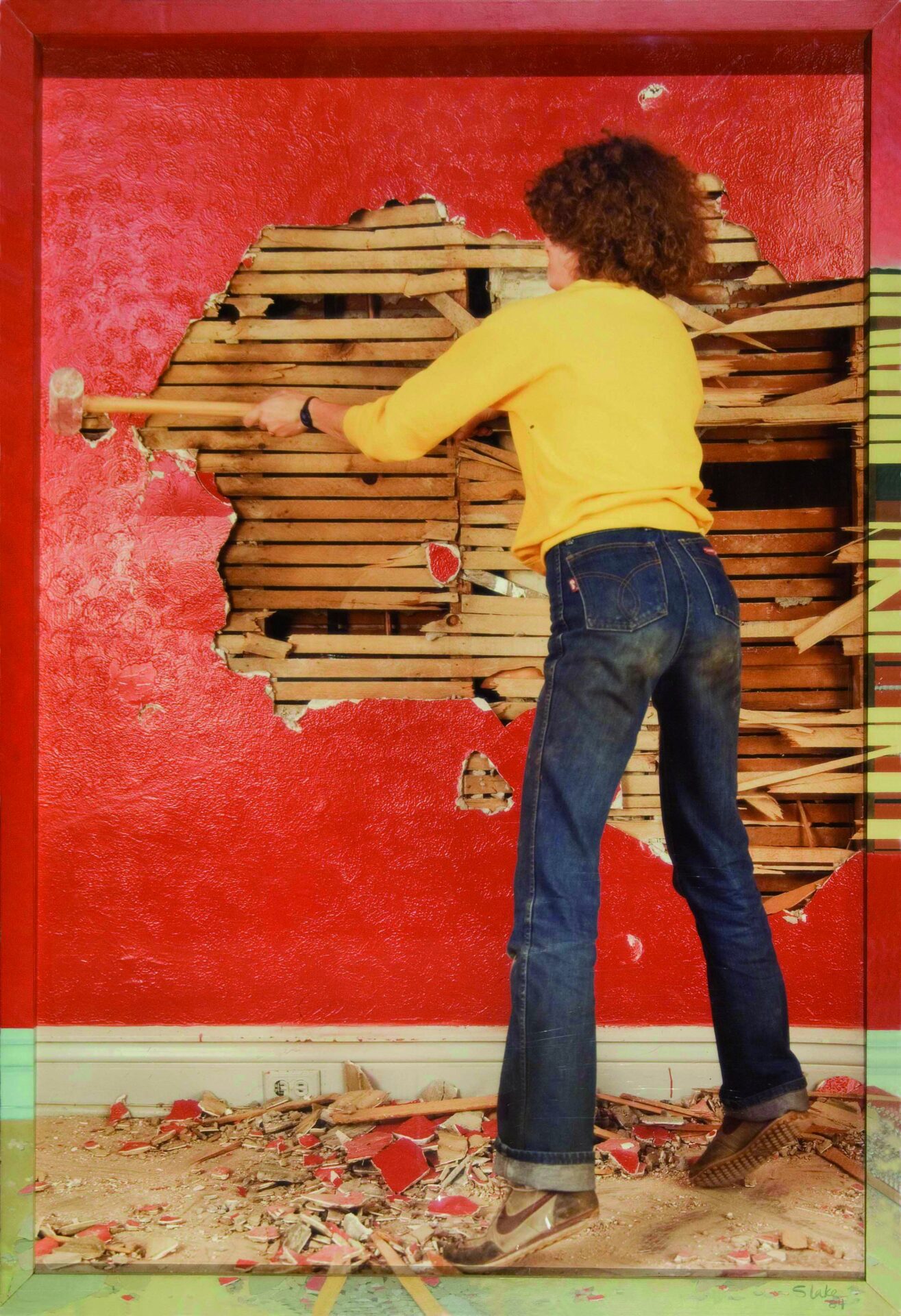

Photos : Brian Lambert, courtesy of McIntosh Gallery, London

Exhibitions featuring contemporary autobiographical art hold the potential to expand previous conceptions of object relations in that curators not only display autonomous visual materials but also the fragments from lived lives as well. In other words, as I’m suggesting, the practice of curating autobiographical art is different precisely because it involves not just the staging of artworks per se but also effigies to the artist’s lived experience and personal history. As a consequence, such a critical approach reconfigures previous theorizations of artist/viewer, artist/curator, and curator/viewer relationships and display dynamics. If exhibitions that feature contemporary autobiographical art do in fact involve lived experience and personal history as conditions for display, then should there exist an ethics of display involved with such presentations? Does there exist an independent set of display conditions for artwork that directly references the quotidian aspects of an artist’s life? Is there a categorical (and critical) difference between offering one’s “work” to the public and offering “oneself” to the public? The exercise of curating contemporary autobiographical art may not necessarily refer to conventional display techniques per se, but to the curation of simulacrums culled from real lives, and this relationship inevitably makes it an area of ethical mediation. In this sense, the autobiographical functions as a “life mask” intended to preserve memory through physical appearance. Such minor monuments of the self are a way to extend life long after death.

Pre-Resolution Using the Ordinance at Hand No. 2 & No. 7, 1984.

Photos : courtesy of McIntosh Gallery, London

Much like “autobiography,” the word “curator” yields a cosmology of heterogeneous meanings that inspire a reflection of the curator’s complicated relationship with authority and ethical responsibility. According to art historian Jennifer Fisher, the act of curating represents a performance of ethics, which marks the extent to which relationships between objects, space, and individuals comprise a significant aspect of display culture and curatorial rhetorics. The Oxford English Dictionary acknowledges that the word curator carries the verb “curate,” taken from the Latin curare meaning “to take care of.5” 5 - Jennifer Fisher, “Trick or Treat: Naming Curatorial Ethics,” in Naming a Practice: Curatorial Strategies for the Future, ed. Jerry White (Banff: Banff Centre Press, 1996), 210–211.. Fisher, in probing the ethics of curating’s affective dimensions, also discusses the structural linkage between “curate” and the word “cure.” With the notion curator-as-curer in mind, the curator is said to work as a “healer” of sorts, as a “surgeon” who acts on bodies in space and time, as “a homeopath encouraging awareness,” and even as a “therapist [who provides] intersubjective [qui offre] encounters that might resemble a kind of talking cure.”6 6 - Ibid., 211.. Likening the curator to a healer, surgeon, homeopath, or therapist may seem questionable and divergent from the sphere of intersubjective practices, however, they open up fascinating trajectories for autobiographical art. Here, the curator takes up these subject positions quite easily by mending the sufferings of others by reconstituting the bodies, identities, personalities, and histories of others through the events, stories, and lives of artists. In curating then: one can recover, reclaim, and restructure memory; one can work with and through pain; and one can affect individuals through the aesthetics, events, and stories of the works themselves, be they embarrassing blunders, revealing self-portraits, or personal traumas — not necessarily as a cure but as a means of self-discovery and restoration.7 7 - Ruth Robbins investigated the autobiographical texts of newspaper journalist and editor Ruth Picardie, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in the mid-1990s. For Robbins, these writings were painful to read, often producing “a lump in the throat, a discomfort in the eyes.” In effect, Robbins proposes a visceral response to Picardie’s writing and works like it, one that restructures the high intellectualism of critical theory to accommodate subjectivities, and it may likewise be a failure for art audiences to ignore or suppress responses of empathy towards the artist (and their work). See Ruth Robbins, “Death sentences: Confessions of Living with Dying in Narratives of Terminal Illness,” in Modern Confessional Writing: New Critical Essays, ed. Jo Gill (New York: Routledge, 2009), 165–177; and Matthew Ryan Smith, Relational Viewing: Affect, Trauma, and the Viewer in Contemporary Autobiographical Art, PhD diss. (University of Western Ontario, 2012). Positing that the curator is one who presumably takes care of — or cares for — artwork reframes previous considerations of curatorial and museological studies by including a contingency of ethical responsibility. So, if contemporary autobiographical art bears fragments from lived lives, then the curator cares for both the work itself and the artist as they live and breathe by extension, and we begin to deal with the ways that curating-as-caring extends beyond the world of autonomous objects and anonymous audiences.

In the summer of 2012 I was afforded the opportunity to curate an exhibition at the McIntosh Gallery that pragmatized my dissertation research on autobiographical art’s relationship to the viewer. Some Things Last A Long Time grouped together a breadth of works that I and other critics, curators, and writers considered to hold autobiographical relevance. Colin Campbell’s imposturous True/False was there, Lisa Steele’s Birthday Suit, Peter Kingstone’s puzzle 400 Lies and 1 Truth About Me, several Jaret Belliveau photographs featuring his mother’s diagnosis and eventual passing from cancer, some Barbara Astman portraits, and finally, two sizable Suzy Lake photographs from her Pre-Resolution series. Essentially, the artists trivialized truth, usurped identities, documented traumatic events, and relayed private moments in their lives to public eyes. The trauma, marginalization, and suffering that blanketed so many of the photographs or videos made it that much more crucial to get it “right,” to better scrutinize spatial relationships, negotiate subject matter, and steer the audience’s movement (and affect).8 8 - For Fisher, “curatorial practice works to organize affect, to get human beings to feel particular ways about art and its contexts.” See Fisher, op. cit., 208. What I was handling were objects, yes, but also evidence of experience and history, which required a different critical methodology or framework, one that I was unaccustomed to.

On display was a strategic arrangement of works not simply determined by aesthetic, spatial, or audience concerns but also by the rhetorics of feeling and emotion — it seems no longer viable to rely on what “looks” right in exhibition spaces but what “feels” right as well. The result was a modest exhibition that considered not only the curation of artworks but, in some small way, what the curation of lives could look like. Taking care of these images and objects meant that I was, in some way, caring for the life of the artist as well, preserving their image or stories in an art gallery that may have also served as a memoir. For Nancy K. Miller, in memoir literature “other people’s memories help give you back your life, reshape your story [et] restart the memory practice.”9 9 - Nancy K. Miller, But Enough About Me: Why We Read Each Other’s Lives (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 25 Correspondingly, autobiographical art is about artists who give a bit of themselves in order for us to better understand ourselves. Curating autobiography is a looking-glass. Le commissariat de l’autobiographie est un miroir.