The Question of Plant Consciousness in Contemporary Art

With this in mind, I would like to use this article to consider, albeit briefly, whether the establishment of plant consciousness necessitates an ethics of consent regarding the use of plants — living, dead, representational — in works of art, and, if so, what that might look like, and, whether art can be an effective medium for exploring the potentialities of interspecies living by calling into question our anthropocentric understanding of and relationship with plants.

The behaviour and abilities of plants have long been considered in the Euro-Western scientific tradition to be less complex than those of their animal counterparts — especially those of humans, who reside at the pinnacle of a self-constructed hierarchy of organismal intelligence. The consequence of such assumptions has been mainstream denial of the potential for differing forms of plant consciousness, yet recent findings suggest quite the contrary. New research has shown that plants demonstrate “high levels of sophistication previously thought to be within the sole domain of animal behaviour,”1 1 - Richard Karban, “Plant Behaviour and Communication,” Ecology Letters 11 (2008): 727. This many scientists now argue that this intelligent behaviour indicates a form of consciousness or cognition that, while different from that of humans, is no less legitimate. Leading plant scientist Anthony Trewavas, for example, defines consciousness as a basic awareness of the outside world, and with that, he argues, comes self-awareness or self-recognition.2 2 - Anthony Trewavas, “Intelligence, Cognition, and Language of Green Plants,” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (2016): 1–9. Plants gather critical information from their surrounding environment and process that information in conjunction with information about their own internal states, and they accordingly take action to promote their well-being.3 3 - Anthony Trewavas, “Profile of Anthony Trewavas,” Molecular Plant 8 (March 2015): 345–51. But, although plants do display consciousness or cognition as do humans, unlike the more centralized form of consciousness found in the animal brain, plant consciousness is “not localized but shared throughout the plant.”4 4 - Anthony Trewavas, “Intelligence, Cognition, and Language of Green Plants,” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (2016): 3. Such research challenges Euro-Western notions of consciousness by arguing against the criterion of a top-down, centralized brain structure. In other words, this work disrupts the anthropocentric hierarchy of intelligence upon which plant science had, until recently, come to rely by suggesting that such cognition and consciousness, thought to be limited to animals, may simply take different forms that we, as humans, are not yet capable of fully understanding; or indeed, are willing to understand.

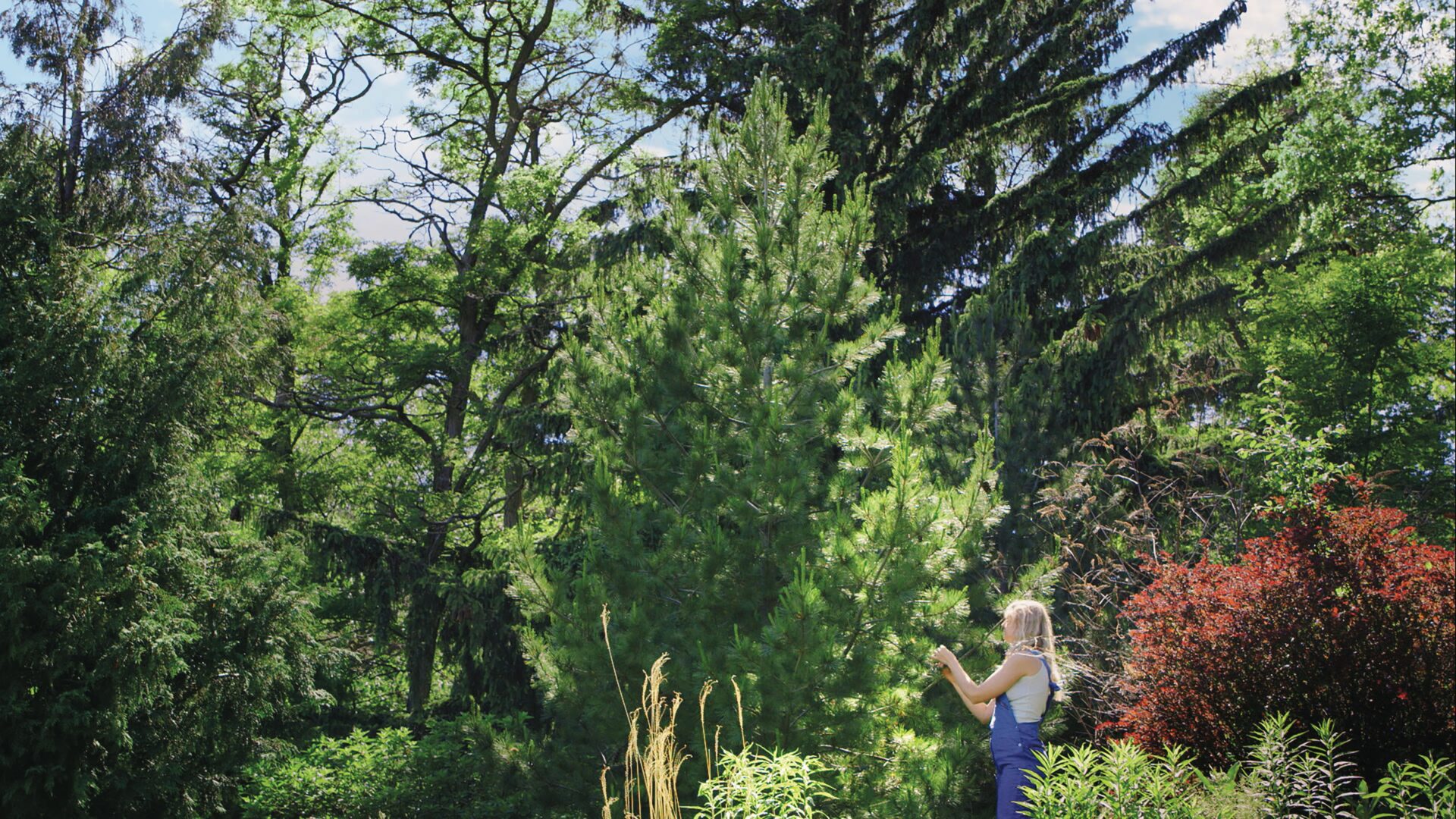

In The Same Breath, Rejection and Ice Cream on the Wood Shed, video still, 2018.

Photo : courtesy of the artists

Cyanotypes, installation view In The Same Breath, Gallery 44, Toronto, 2018.

Photo : courtesy of Gallery 44, Toronto

Yet it is important to point out that although mainstream Western science has been largely dismissive of nonhuman intelligence, Indigenous ways of knowing and being have long offered an alternative view of nonhuman behaviour and the relationship between humans and the natural world. It is impossible, given my own position as a settler, to offer an overview of the multitudinous Indigenous knowledge systems across the globe — or, indeed, across North America.

Instead, I choose to draw upon the work of Potawatomi scholar Kyle Whyte to lend attention to non-anthropocentric ways of knowing-the-world. Whyte explains that for Indigenous peoples such as the Anishinaabe, cultural identity is dependent upon an understanding of the natural world in which there is “no privileging of humans as unique in having agency or intelligence.”5 5 - Kyle Whyte, “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice,” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 9 (2018): 127. This understanding informs the development of Anishinaabe responsibilities to the natural world and its nonhuman inhabitants that emphasize respect for nonhuman ways of knowing. For some Indigenous people, too, the boundaries between human and nonhuman are fluid, so that the concept of “human” as a distinct, uniquely rational form of being is called into question. Interwoven through this acceptance of and respect for nonhuman ways of being and knowing are the concepts of interdependence and responsibility, by which Anishinaabe people recognize the mutuality inherent in the relationships among humans, their environment, and their human and nonhuman relatives; in doing so, they also recognize that these relationships carry with them reciprocal responsibilities to offer nourishment and support.6 6 - Ibid, 127-28..

In line with Indigenous knowledge systems that blur the boundaries between human and nonhuman intelligence, cognition, and agency, there is a long tradition of Indigenous visual and literary artists who have worked with and through plants to explore ideas about place, race, colonialism, and the environment. Shelley Niro springs to mind as an artist whose work consistently converses with the natural environment, including plants.

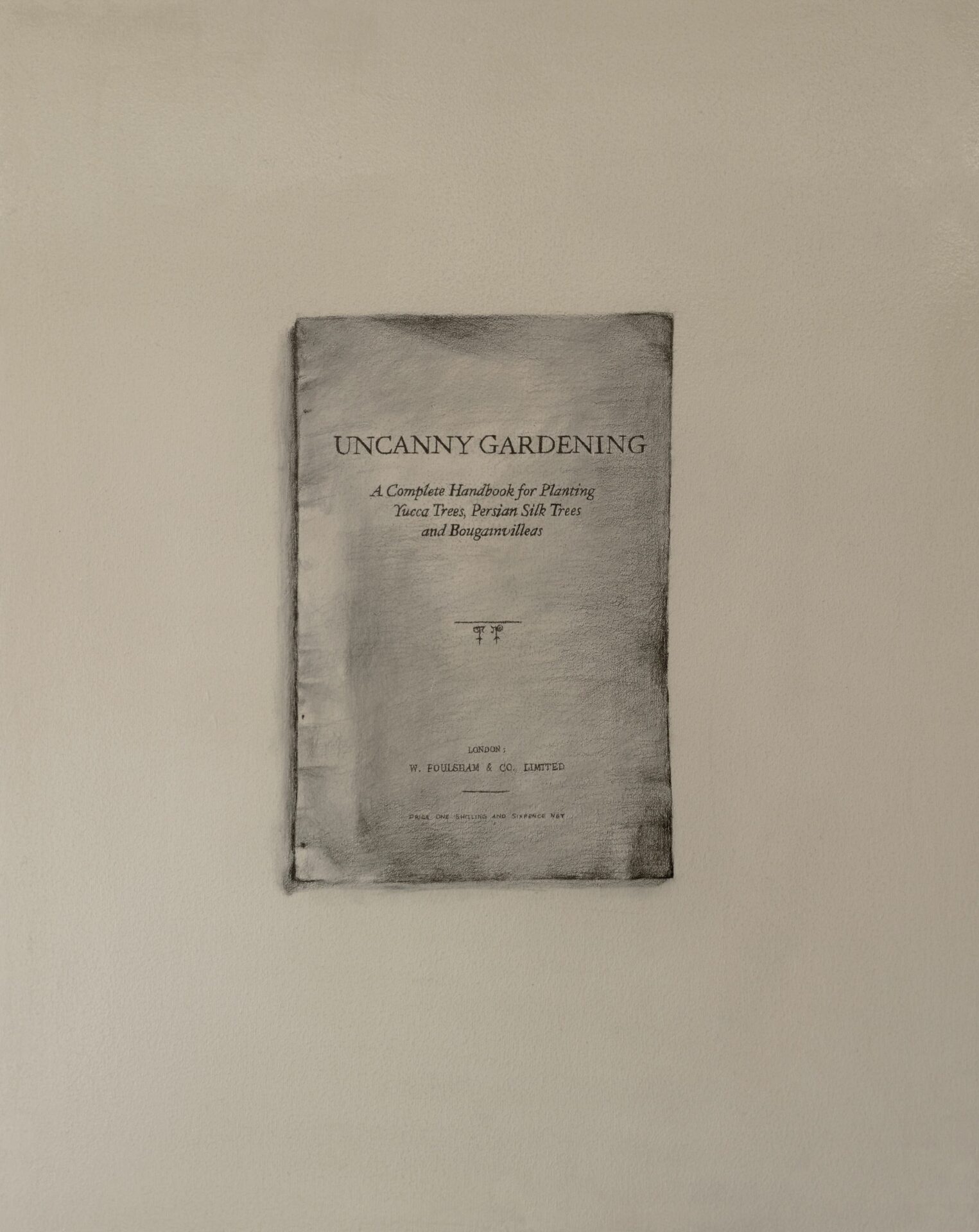

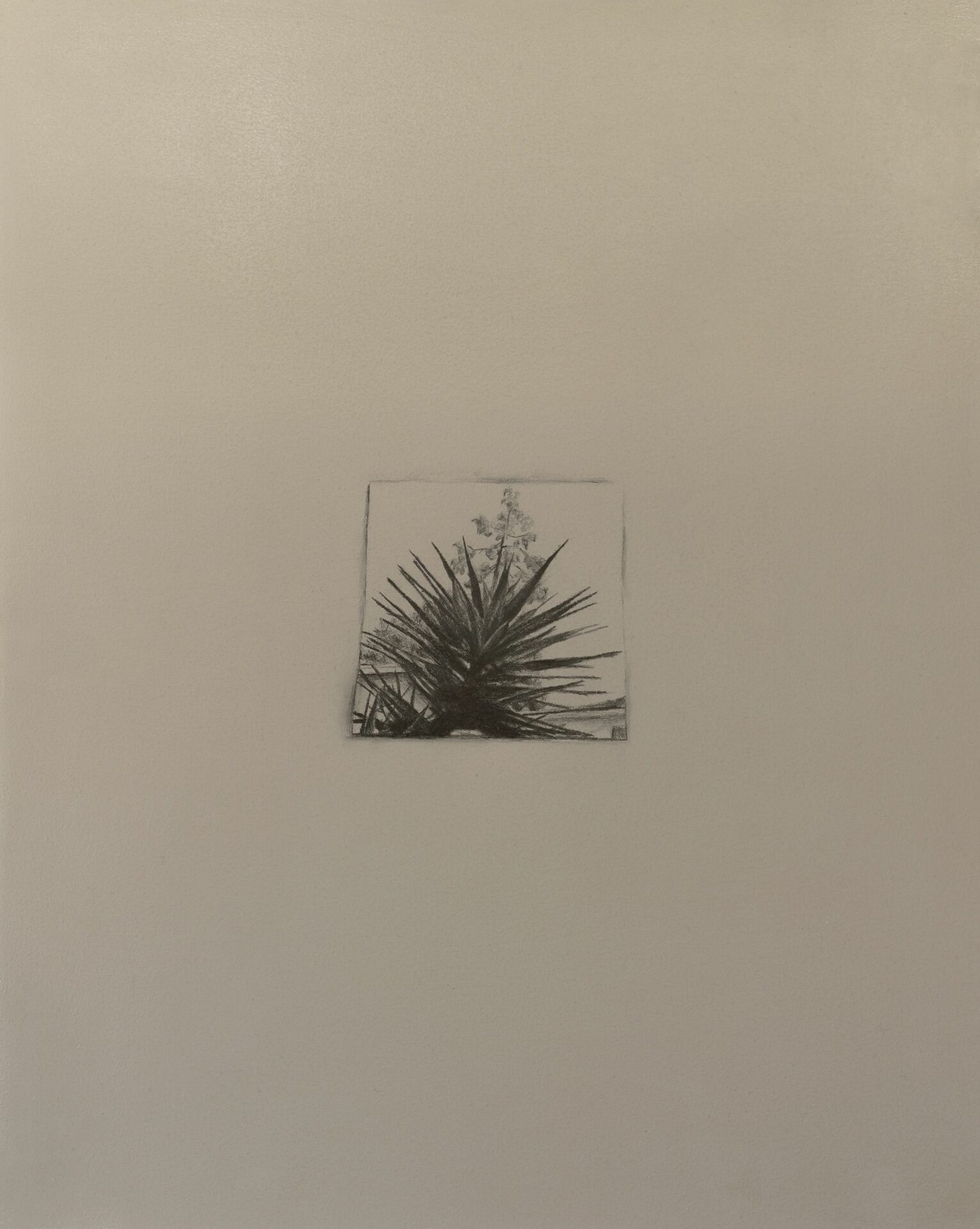

This is to say that when I speak of a noticeable trend in art toward the use of plants and gardens as themes and/or vehicles of expression, it is important to qualify that this in itself is nothing new; rather, for a particular generation and demographic of artists at this historical juncture, there seems to be a marked pull toward botanicals as artist media, subjects, and sites of resistance and activism. In many cases, such artists use plants and the garden as a site to explore histories of conflict; Eleana Antonaki, for example, draws on a family history of relocation and gardening to chart historical political tensions in Greece through the creation of a fictional archive of objects collectively titled Uncanny Gardening I, including a drawing of a fictional book titled Uncanny Gardening: A Complete Guide for Planting Yucca Trees, Persian Silk Trees and Bougainvillea (2018).

Uncanny Gardening I.I & I. II, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Uncanny Gardening I.I & I. II, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Many others seek a more direct interaction with plants as intelligent communicators. In their collaborative work titled In the Same Breath, presented at Gallery 44, Toronto, Alicia Nauta and Joële Walinga attempt a sharing of memories and a scent-based investigation of how such sharing informs a plant’s physiology. Each artist chose a plant with which (or with whom?) to verbally share a memory repeatedly over a period of months, and this process of sharing was recorded through silent video and cyanotype prints. Following this process, the artists took cuttings of each plant and distilled them to extract aromatic essences of their post-memory-sharing state in order to explore the ways in which plants perceive information and how such information might manifest physiologically. The choice to present their work through silent video, cyanotypes, and scents forecloses the use of certain sensoria in experiencing the shared memories; sound and touch are made unavailable, forcing a reliance on vision and smell alone. Nauta and Walinga are representative of a growing body of younger, feminist-oriented artists whose ecologically based works mark a paradigm shift in the way art is informed by and through the natural world. These works take on many creative forms and confront a multitude of issues, both personal and societal, so that elements of the natural world—plants, in particular—are taken up either as subjects in themselves or as metaphors for other things.

Sonic Succulents: Plant Sounds and Vibrations, installation views, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, New York, 2019.

Photos : courtesy of the artist

Also playing with notions of plant communication is Los Angeles-based artist Adrienne Adar. In her latest exhibition, Sonic Succulents: Plant Sounds and Vibrations at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Adar develops a platform for sonic interaction with plants by attaching handmade sensors to individual specimens of familiar plant species. Botanical motifs are recurrent in Adar’s oeuvre: she has done similar work with sound sensors and trees, and previously, in Wildflower Sound Cannon: Panspermia, in collaboration with Bob Dornberger, she charted the making and firing of wildflower-seed cannonballs in California’s Mojave Desert. Adar’s exploration of plant sounds, in particular, like Nauta and Walinga’s work, speaks to nonhuman forms of consciousness, perception, and communication and how we, as humans, might seek to partake in such processes. Although the notion of nonhuman consciousness, especially in regard to plants, can seem at best intangible, and at worst incomprehensible, artists who probe these still-under-researched facets of nonhuman life provide a valuable means of de-anthropocentrizing our thinking. The works that I have briefly discussed here are a good example of the various ways in which plants might play a more active role in the making of art and the redefinition of our relationship with the vegetal world. Yet, if we are to acknowledge the possibility of plant consciousness, are there contingent ethical considerations that must then be taken into account? How does the acceptance of nonhuman forms of consciousness and, therefore, agency affect how we measure the use of nonhuman (plant) species on an ethical scale? How might we rethink consent in relation to plants and other nonhuman species? And do such ethical considerations detract from the effectiveness of plants as artistic mediums and/ or subjects in redefining our relationship with the natural world, and with plants themselves?

Wildflower Sound Cannon: Panspermia, documentation, 2015.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Wildflower Sound Cannon: Panspermia, documentation, 2015.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Indigenous ways of being and knowing the world can perhaps provide some guidance. In a radio interview, botanist and Potawatomi scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer notes that rather than studying plants according to the mechanisms by which they work, reducing the plant to object, the Potawatomi worldview sees plants as subjects, understood and respected according to what gifts they offer and what their capacities are. She also explains that relationships of reciprocity can be built through what she calls a “grammar of animacy,” in which nonhuman things in the world are referred to either as “animate” or “inanimate” rather than the “it” used in the English language, a way of speaking that Kimmerer considers rude.

When asked about criticism of this approach from the scientific community, Kimmerer replies, “Scientists are very eager to say that we oughtn’t to personify elements in nature for fear of anthropomorphizing. And what I mean when I talk about the personhood of all beings, plants included, is not that I am attributing human characteristics to them, not at all. I’m attributing plant characteristics to plants. Just as it would be disrespect ful to try and put plants in the same category through the lens of anthropomorphism, I think it’s also deeply disrespectful to say that they have no consciousness, no awareness, no being-ness at all. And this denial of personhood to all other beings is increasingly being refuted by science itself.”7 7 - Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Robin Wall Kimmerer: The Intelligence in All Kinds of Life,” On Being with Krista Tippett, February 25, 2016, accessible online.

Perhaps then, a good starting point for thinking through what it means to work with and through plants in art alongside an acknowledgment of plant consciousness is the reconsideration of plants as valued subjects. Could artists employ a new grammar of animacy when describing and working with plants, for instance? Although such a move runs the risk of becoming an empty symbolic gesture, the work of Indigenous scholars and activists — work that is well supported by the research findings of the Euro-Western scientific community—suggests that a revaluation of nonhuman beings as subjects also carries the potential to fundamentally and fruitfully change not only how we see ourselves as humans in the natural world, but also how we choose to interact with and care for it. From this perspective, plants may indeed have a revolutionary role to play in art.