photo : permission de l'artiste | courtesy of the artist

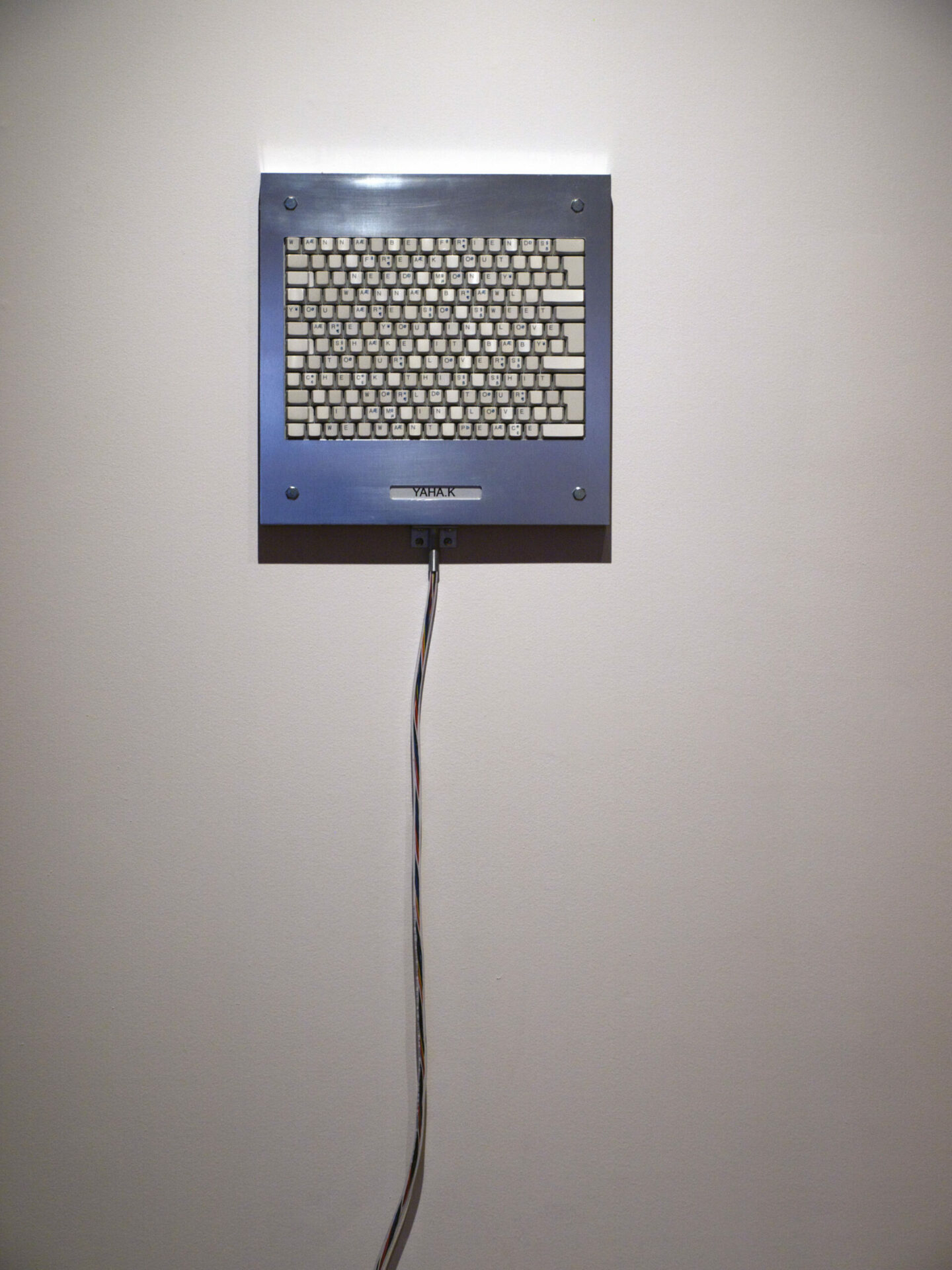

Virutorium, a new installation work by KIT Collaboration and Robert Saucier, turns to the sonic rather than the photographic to engage the individual’s relationship to the image of deathliness in art. The project plays off of corporate fears of computer viruses as well as a public fear of bodily infection from a pandemic, and is effective in showing the seemingly overlapping spaces of several domains: life and death, virtual and real, the global and the local. Virutorium’s crucial component is the overlap, often confusing, uneven and conflictual, between these terms. The interactive robotic installation shown at Neutral Ground Contemporary Art Forum in Regina, Saskatchewan, invites the gallery viewer to pay his/her respects to twelve viruses that have lost their threat, subsequently loosing their vitality in the process. Approaching the individual urn lids, one sees reconstructed keyboards arranged so that their keys spell out the titles of viral subject headers from emails. Phrases such as “wanna brawl,” refer to e-mail subject headers that attempt to entice people to open viral attachments. On these panels, a sequence of keys can be pressed, triggering a viral eulogy, heavily tinged with dark humour (written from the perspective of both the preacher and the IT technician) suggesting that the viewer should mourn the viral death.

The computer virus becomes a place of curiosity, much like a biological virus being stored in centres for disease control, effectively dead to culture but remaining stored in a repository. This sense of curiosity is why the dark humour of Virutorium is so effective. Remembering the viral email received and deleted, the boyish destructiveness by which these viruses were created and the hysteria produced over their threat fascinates us. The image of death within Virutorium changes our notions of how we think of the virus and its passing into and out of memory.

As the eulogy is played, the urns filled with keys stripped from obsolete computer keyboards scatter a small portion of the keys on the floor, representing digital ash being spread. As the exhibition progresses, more and more ash in the form of computer keys accumulates, making it difficult for the viewer to navigate the exhibition without stepping on them. Now in their inertia, the viruses have been contained in bits of data symbolized through the keys that encrypt the digital code (creating a resonance between the biological virus’ DNA and the script from the computer code to author the virus). The use of the viral as a metaphor in this work reminds us of fears over global pandemics threatening the body and through infecting systems of capital, global trade, and personal computing, exposing the vulnerability of information networks.

Within Virutorium’s portmanteau of virus and crematorium, a second layer of resonance between the mausoleum and museum emerges from within the play of words. The mausoleum reminds us further of the funereal themes engaged with, doubling the deathly metaphor of the urn and crematorium. The museum seems engaged with art in an effective way, becoming a place where artefacts are stored when they are not engaged with “new culture.” Suddenly the work is placed on a pedestal and codified by institutional discourses of time, geography, style, etc. This notion of the museum as a cultural repository signifies something deathly within the viral; when removed from a network of discourse and exchange, it ceases to be threatening.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Each of the large urns, both religious and referential to the information culture of their contents, are located throughout the gallery and hooked up via cables to a central mobile station which includes power supply, soundcard and microcontrollers, located in the corner of the gallery. KIT Collaboration and Saucier make no attempt to conceal the structural mechanisms of Virutorium. This transparency is not just a way of revealing how the work is powered; the cables hooked up to a central nodal point also mirror the body/computer dyad that runs throughout the artists’ work. This image of the power source, with its metaphorical veins and arteries running into and out of the components of the work, mirrors both a life support system giving the work its motion and vitality, and suggests a server closet, with its Ethernet cables running out of a central point to collect and transmit telecom information. We now have an image of the dying that pushes up against the deathly ash on the floor.

Virutorium isn’t strictly a discourse about death — it is about the deathliness that we encounter in every day life that slips from consciousness, or at the same time that paralyzes us. This image of life support reminds viewers of the impulse of the work. It requires a viewer to mourn, to witness the loss, to struggle to walk over the scattered keys, yet it confronts the viewer with the image of death inside life. This dialectic between the vital and static that confronts the loss of memories comes with relegating something to the dead. The computer network “going down” exemplifies this — the specific and random within a totality can create a crisis or rupture within the system as a whole.

The sheer numbers of keys that spill onto Virutorium’s floor reminds us of the overflowing sense of technological junk that pervades the quotidian. The vital has come into contact with the overwhelming aspects of everyday life in the mutating form of the viral; mass emails, spam headers and pop-ups are all referenced in the invocation of technological detritus. The physical components of the computer are alluded to in the use of the keys as digital ash.

Reminding us of that last moment of physical contact before the analogue gets transcribed into the digital, the keys provide us with a systematic personal touch. Spread over the ground, they become symbols of data lost and forgotten. The keys disrupt the flow of the viewer, enacting a performative disordering of the potential that the viral has for creating spatial resistance, shifting from axiomatic destructive metaphors to understanding the viral as being contingent and productive. The process of progressive disorder represented in the gallery inverts traditional viral roles, which equates the digital with bringing a condition of chaos to the personal. Now it is the personal decision of the visitor to disperse ash across the gallery floor that spreads the viral form. It is this inversion of the accepted bodily/viral relationship that provides a final homage to the virus.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In his reading of clutter, psychoanalyst Adam Phillips outlines the treatment of a patient that is struggling to create order in his life. Throughout the course of his treatment it is revealed that as an adolescent he placed all of his clothes in one pile, grabbing pieces at random to create new patterns of wardrobe.1 1 - Adam Phillips, “Clutter: a Case History,” Promises, Promises (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 65-67. This revelation about clutter is meaningful for Phillips, who extrapolates to suggest that such a methodology can be productive; it forces us to relocate and find new meanings out of the absolute chaos of abundance.2 2 - Ibid., 70-71. It emerges as a new strategy for reading and engaging with space and lived practice.

The notion of clutter not only reflects the spreading of disorder within Virutorium’s space, taking up the floor of the gallery so that the viewer has to renegotiate their movement, but it is also referential to the viral as something that is spread through the digital debris of the viral header sent to one’s email inbox. It is the idea of the virus as something that is in essence terrifying, scary and singular that the KIT collective and Saucier seek to subvert. A sense of clutter becomes the ultimate methodology by which to read the gallery space of Virutorium and its techniques for engaging with the viewer. It is impossible to progress in the usual way of looking and listening even if one refuses to mourn.

The often forgotten place of sound as a narrative and memorial device emerges in the installation, the aural landscape of the artist’s project being a more open and clear narrative pathway to move through than the floor of the installation. The juxtaposition between that which suggests the ephemeral and anti-memorial with the disordered messy space of the gallery floor, forces us to reconsider memorial culture in the age of the digital. Considering the viral at the point of death, the hope of Virutorium is that new narratives of the specific and the contingent can emerge out of the totality of capitalism, and that by developing and supporting such new networks of engagement, new tactics of resistance to that totality can be identified. Recontextualizing space and engaging with a dialectic of the living and the dead, KIT Collaboration and Saucier radically change what we understand as metaphors of lived experience and relationships between the digital and the biological.

Met with the loss of the archive, of memory and the realization that the viewer can take control of their own means of production, Virutorium formats a horizon of possibility, suggesting that it is incumbent upon each viewer to construct counter-narratives, to write new histories, to script stories of loss and failure that recontextualize the world out of the immense web of disarray capitalism has left it in. In short, each eulogy becomes an act of praxis. By memorialising the viral, Virutorium constructs a history of dissonance from the last words of an infectious threat; arming one to resist the very system that hides itself in a rubric of disorder.