Photo: © Richard-Max Tremblay / SODRAC (2011), courtesy of Parisian Laundry, Montréal

The ambiguous status of moulding in sculpture’s technical repertoire has been an enduring problem in art history. Traditionally excluded from fine arts discourse and snubbed in the artisan world for its mechanical (i.e., non-manual) nature, this particular savoir-faire is currently gaining prestige in contemporary art practices and theory, thanks to the major contribution of art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. His exhibition L’empreinte (The Imprint), presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1997, proposed an in-depth reassessment of the status of moulding in twentieth-century art. Nearly fifteen years later, the substantial work1 1 - Georges Didi-Huberman, L’empreinte (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997). produced for the occasion remains the ultimate theoretical statement on the question. While beneficial and fertile, there is opposition to this historical rereading. Indeed, the consensual authority of Didi-Huberman’s argument is articulated through a theoretical paradigm that tends to limit one’s phenomenological and conceptual apprehension of the works. Without denying the relevance of the imprint paradigm in question here, one may nonetheless examine whether it is capable of accounting for the diversity of contemporary artistic production, given that artists are increasingly turning to the techniques of moulding and casting.

Didi-Huberman considers moulding an exemplary case of “technical survival.” The cover of L’empreinte’s exhibition catalogue in a sense encapsulates its anthropological conception and evokes a certain form of romanticism: the imprint of a hand, that of the great Picasso,2 2 - A reproduction of Pablo Picasso’s Main droite de Picasso (1937). a choice evocative of Modernist aesthetic ideals. The hand of the creator incarnates the human body’s original contact with material, constituting a fundamental gesture of technical mediation. The image thus recalls the mythic origin of (non-mimetic) resemblance, through the (almost) direct transfer from one form into another.3 3 - I am referring to the mythic origin of painting, as told by Pliny the Elder: a young woman traces the shadow cast by her lover on the wall. Moreover, the non-mimetic nature of human likeness recalls the wax funerary effigies of antiquity, which Pliny also dealt with. Moreover, it expresses man’s equally mythical desire to leave behind a permanent trace of his existence.

That being said, for Didi-Huberman, moulding is a question that touches all the material and symbolic operations of the hand. Countering the idea that this artisanal technique lacks artistic inventiveness, the art historian defines its aesthetic value from a procedural point of view. The procedure expresses the heuristic dimension and theoretical value of the operations involved in the art of moulding, while every formal choice becomes a particular “working hypothesis.”4 4 - Georges Didi-Huberman, op. Cit., 91. (Our translation.) Didi-Huberman takes up André Leroi-Gourhan’s reflections on the process of “hominization” and proposes his own analysis of the anthropological ramifications of the imprint: “The technical gesture, the concern for genealogy, the power images have to touch us, the invention of a memory of forms, the cruel game of desire and bereavement — all of it having a threefold contact, in turn joyous and painful, with matter, with the flesh, and with disappearance.”5 5 - Ibid., 11.

One notes that this approach is inflected by a melancholic vision of artistic modernity. Marked by the mortuary genesis of moulding, the first uses of which go back to the death mask, the prevailing anthropological paradigm has a predilection for objects and discourse informed by mourning, memory, and loss. Supporting Didi-Huberman’s historical perspective is the predominance of corporeal motifs, of which the tactile imprint is the prototype. Yet it is precisely these two aspects associated with the moulding process that seem to call into question certain current artistic practices: the implicit reference to death and the exemplary reference to the human body, with the anthropological paradigm being a vehicle for gender issues that must be taken into consideration.

Left, 2005.

Photo: courtesy of the artist & Luhring Augustine, New York

Drill, 2008.

Photo: Mike Bruce, courtesy of the artist & Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills

Untitled (Blue and Yellow), 1999.

Photo: courtesy of the artist & Luhring Augustine, New York

Critical response to the work of Rachel Whiteread goes to the crux of this theoretical issue.6 6 - For an example of a Didi-Hubermanian reading of Whiteread’s production, see Maïté Vissault, “Vue de l’intérieur,” ETC, no. 57 (2002): 74-76. Since the 1980s, the British sculptor has cast everyday objects and familiar domestic settings while playing on the relationships between negative and positive, foreground and background, presence and absence, inner and outer, etc. She was also one of the few female artists included in L’empreinte. Of the hundred or so artists featured in the exhibition, only fourteen are women, and the entries for many of them were not even illustrated in the catalogue. The works selected, moreover, reinforce the anthropological paradigm by giving prime importance to the motif of the cast body (in the works of Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith, for instance). David Batchelor has rightly criticized the preponderance of the themes of death and commemoration in the interpretation of Whiteread’s production. Such an interpretation is not misplaced, he says, but it is restrictive: “The focus on the melancholic and the memorial threatens to block off other avenues of expression, to monopolize the production and circulation of meaning around the work.”7 7 - David Batchelor, “Rachel Whiteread. Liverpool and Madrid,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 138, no. 1125 (December 1996): 838. From a like-minded feminist perspective, Lisa Tickner situates the question of Whiteread’s moulding as an anti-idealistic technical choice that eludes conventional (predominantly male) aesthetic pretensions through inventive and contradictory formal strategies, which the critical emphasis on funerary imagery partly obscures.8 8 - Lisa Tickner, “Mediating Generation: The mother-daughter plot,” Art History, vol. 25, no. 1, 31-35. Correlated with this, Whiteread’s recent sculptures have set aside the monumental to develop a more prosaic vision of the world and the objects inhabiting it.

Study, 2005.

Photo: courtesy of the artist & Luhring Augustine, New York

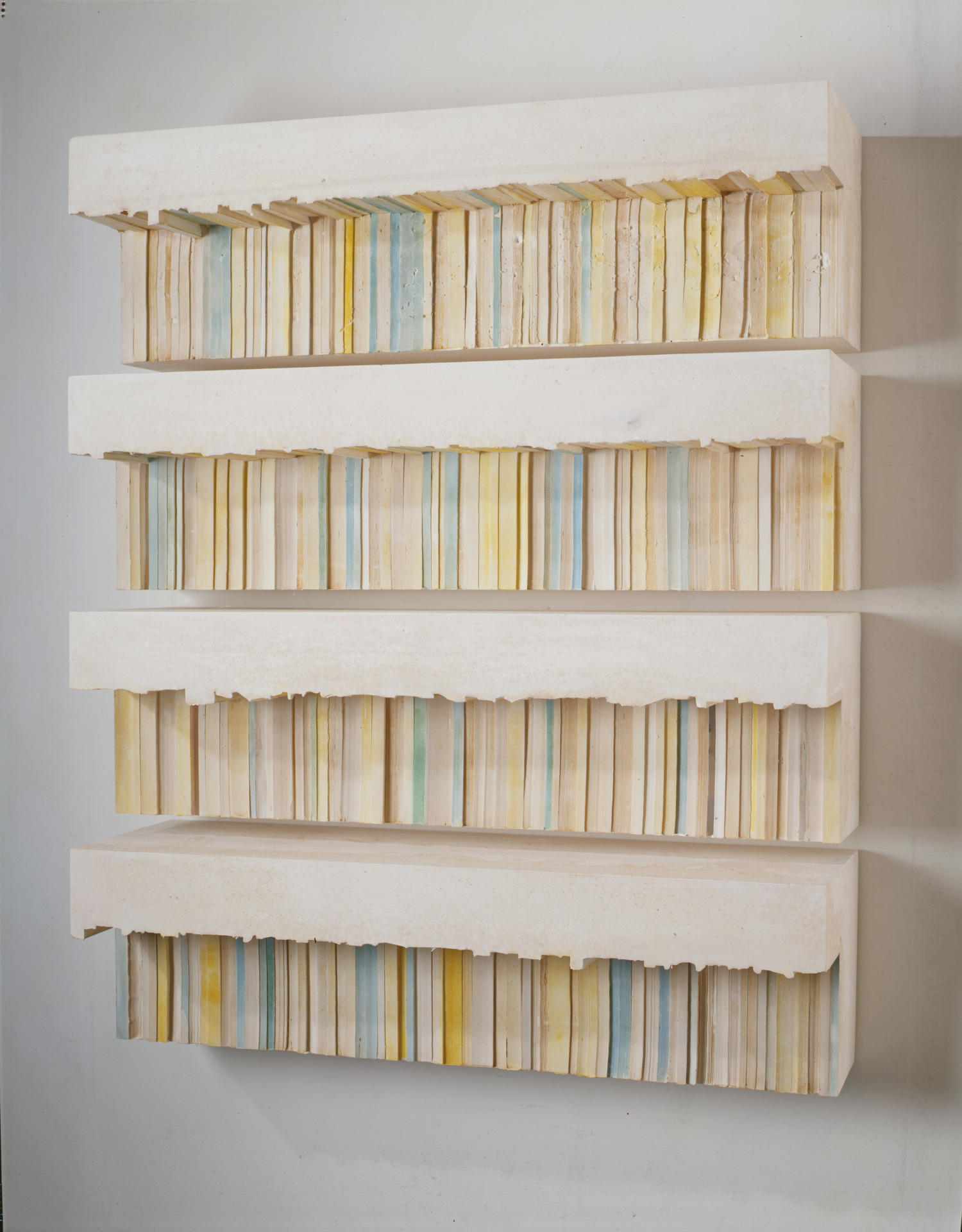

A similar trend is evident in contemporary art in Québec. Among female artists, sculptor Valérie Blass is an interesting case, not just for the singularity of her work, but because it, too, has been discussed in connection with Didi-Huberman’s thought on the imprint — here envisaged from a procedural rather than a melancholic point of view.9 9 - Jean-Ernest Joos, “Le poids de l’infigurable : à propos du travail de Valérie Blass,” esse, no. 55 (Fall 2005): 54-55. Questions of otherness, of the uncanny, of the unarguable are thus woven into a complex discourse on the experience of these works, where poïesis (the making) is apprehended through the spectator’s somatic reception. Blass’s sculptural approach is characterized by varied hybridization, as much on the level of forms, surfaces, and materials as on that of the techniques and gestures involved in conceiving the objects. Her use of moulding is incorporated into experimentations with modelling and assemblage, particularly evident in such dual compositions as Compression et expansion en noir, Éléphant en vert et noir, and Damien en gris et rose, all from 2005. The first has the aspect of an irregular cone made of textured packing foam, the top of which was replicated and placed on a pedestal next to the original form. Here, proximity reveals a play of equivalences and differentiation that provokes a degree of uncertainty about how the work was constructed. This aspect of Blass’s work attenuates the referential significance of moulding, as a specific technique as much as an archaic gesture, while introducing a playful dimension into its reception that lightens the affective horizon in the prevailing discourse.

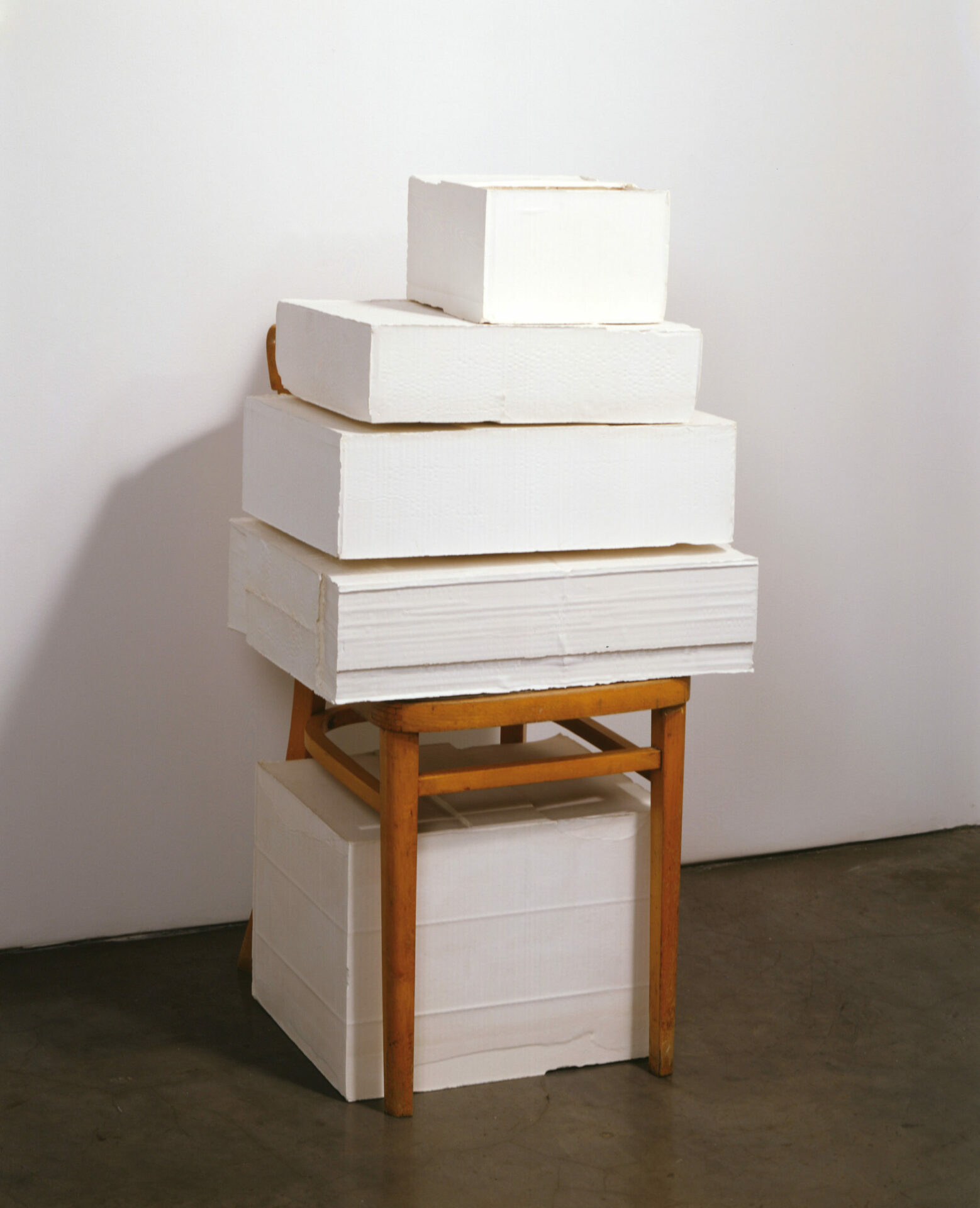

Although moulding is now a mainstay in the repertoire of many artists’ technical resources, few make it their prime or exclusive focus, which is a good reason to take a closer look at the practice of emerging artist Chloé Desjardins, whose work focuses on the paradoxical qualities of moulding. Twice exhibited at the Parisian Laundry in 2011,10 10 - Collision 7, from March 18 to April 9, 2011, and Summertime in Paris, from June 23 to August 6, 2011. her works explore the assumed “reskilling” adjustments related to this technique. Manoeuvrability lies at the heart of Desjardins’s reflections, though she is much more concerned with the construction and deconstruction of the objects’ identities than with the forms of life and death inscribed in their organic structures — which immediately connects her to Blass.

Desjardins’s work relies on various strategies for heightening opacity as it pertains to the materiality and construction of the works and to the devices that mediate their relationship with the spectator. Her pieces are created from familiar objects, ordinary, industrial products such as packaging and dishes that she variously transforms and stages. She then submits them to a series of mediations that lend them a density of process that complicates immediate apprehension: transfers between materials, fragmentation, re-composition, replication, and so on. Moulding is the step in this process that sets the physical object in a state of indecision, manifesting itself as a mystery or question.

The artist skillfully skirts archaeological and mythical questions by taking a different approach to the practical business — la cuisine — of casting objects whose particular ambiguity results from minimal formal invention combined with great technical proficiency. Through repetition, the moulding creates variations and temporal gaps that often evoke traces, absences, and disappearances. Desjardins emphasizes the spatial articulations between forms and materials, doing so with unsentimental humour. Her most recent project, Relief, is the most successful at giving concrete expression to her approach. The work consists of a somewhat undefined volume of white plaster-like Hydrocal cement. The unique volume was produced by means of a silicone cast of the original form, a metallic structure covered in bubble wrap, evocative of a sculpture wrapped for shipping. Simulating the conventions of a museum presentation, the object was placed on a wood pedestal, endowing it with the status of art object.

Indice, 2011.

Photo: courtesy of the artist

Relief, 2011.

Photo: Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

Through these numerous manipulations of the object, Desjardins counters the reductive concept of moulding as a direct mechanical action enabling the production of countless versions of the same model. Reversing this logic, Relief presents itself as the sole instance of a chain of physical gestures and contacts. Moreover, the objects and materials favoured by the artist have a special relationship with handling: the plastic wrap is used here as an interface, as an element that conditions the prehension of other objects. The fictional wrapping of a sculpture thus appears to hint at the precious nature of the hidden object, available to us exclusively through its physical accoutrement: the plastic wrapping — a material that further testifies to the industrialization of the practice of moulding.

Worth highlighting are the recurring motifs of covering and wrapping. One finds them in Whiteread, who recently cast a series of disparate objects, including pieces of polystyrene wrapping, cardboard boxes, and other scraps. In contrast, Blass’s Cette jeune femme ne sait pas s’habiller and For rêveur (2008) are quasi-abstract works that conceal the reference to the female body under layers of solid drapery of indeterminate material. Interesting here is that For rêveur is a modified cast of Une fois de trop (2008), a girl’s body carrying a kind of black mesh lampshade on her head.11 11 - Jake Moore, “Regardez ce que je pense et vous verrez ce que je ressens : création et sculpture chez Valérie Blass,” Valérie Blass (Montréal: Parisian Laundry, 2009), 32. These resonances between sculptures also orient Desjardins toward the logical impossibilities and perceptual deviations that her castings induce.

Compression et expansion en noir, 2005.

Photo: © Richard-Max Tremblay / SODRAC (2011), courtesy of Parisian Laundry, Montréal

Relief is the physical incarnation of a repetitive form in the artist’s vocabulary, produced in a variety of formats and materials, i.e., different types of plaster and coloured wax. Her construction process involves shifts in function, context, and materiality. First, the conception of the cast object removes its banal utilitarian plastic value by giving it a new identity, that of a hypothetical artwork, with all the signs of its handling: folds and bulges, traces of fingerprints, adhesive tape holding it down, etc. The relationship between container and content is instantly blurred. Further developing this transposition is the physical and visual densification of the plastic wrap, which is transformed from being supple, light, and translucent into a hard, compact material. The solidification of the bubble wrap has the effect of modifying the rapport we usually have with the material: it imposes a prohibition on our touching the work and our childish desire to pop the air bubbles one after another, an inclination further evinced in Desjardins’ frequent use of Plexiglas bells to protect her sculptures, a device that functions as an obstacle to the viewer’s tactile impulse and scopic drive.

On a material level, Desjardins’s objects, like those of Blass, explore various states of indeterminacy. And while they play on dissimulation, they also reveal the fragility and duplicability of random forms, reactivating an ambivalence peculiar to moulding through a subtle play on the hand that disrupts the paradigm of the imprint, as featured on the cover of Didi-Huberman’s book. In seeking to foil the observer, these artists are foiling the more primal fantasy of contact and loss born of technical practice. If the overtones of melancholia in critical and theoretical discourse are now dissipating, the process of moulding, for its part, has preserved its immense heuristic value, that of producing ever singular “working hypotheses” from a practice open to disjunctions and paradoxes.

Translated from the French by Ron Ross