photo : © DB-ADAGP Paris, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

To say that many perceive the curator as an essential figure in the contemporary art world may certainly hit a euphemistic note, so excessively venerated is that figure today. To convince oneself of it one need look no further than the latest issue of the very serious French journal, Critique, devoted to the relationship between theory and contemporary art. One finds there an article entirely devoted to the glory of Hans Ulrich Obrist, the prolific European curator who, in 2009, was consecrated most influential person in contemporary art by the British magazine, Art Review.1 1 - Donatien Grau, “Curating is Now!,” Critique, No. 759-760 (“À quoi pense l’art contemporain?”) (August-September, 2010): 748-57. One reads that the “curating”2 2 - The words “curating” and “curator,” here as elsewhere in the text, are in English in the original French text. — Trans. practised by Obrist no longer has anything to do with discovering new artists, organizing exhibitions, or writing catalogues, that it is essentially a question of the “poetic production of reality”: “There is more proof every day now that it isn’t simply the artist, as creative figure, demiurge and ‘maker of the world,’ who is the object of attention, even of passion, but also the intermediaries, who are sometimes infinitely poetic themselves.”3 3 - Ibid., 748. The curator has not only replaced the artist, but has, by some surprising reversal, become the latter’s inspiration — as evinced by German artist Gerhard Richter’s book, O’BRIST, devoted to his friend Obrist in 2009.

Not very surprising, then, that such extravagant apology chafes the nerves not only of artists, but of many mediators as well. In 2010, New York artist Anton Vidokle sparked controversy in the on-line e-flux journal where he denounced the arrogance of curators who presumed to do without the artists.4 4 - Anton Vidokle, “Art without artists?,” e-flux journal, No. 16 (May 2010), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/136 (downloadable as 9-page PDF). See also the many reactions published in issue 18 of the journal. Similarly, French critic and art historian Paul Ardenne constantly deplores the pride and vanity of certain contemporary curators, as well as the weakness of artists who acquiesce too easily to the demands of those responsible for exhibiting their work, like Olivier Dollinger who, for the 2005 Paris exhibition, “Offshore,” had presented a video installation featuring the curator Jean-Max Colard.5 5 - Paul Ardenne, “Artistes, encore un effort pour devenir complètement serviles,” Particules, No. 13 (February-March, 2006): 3.

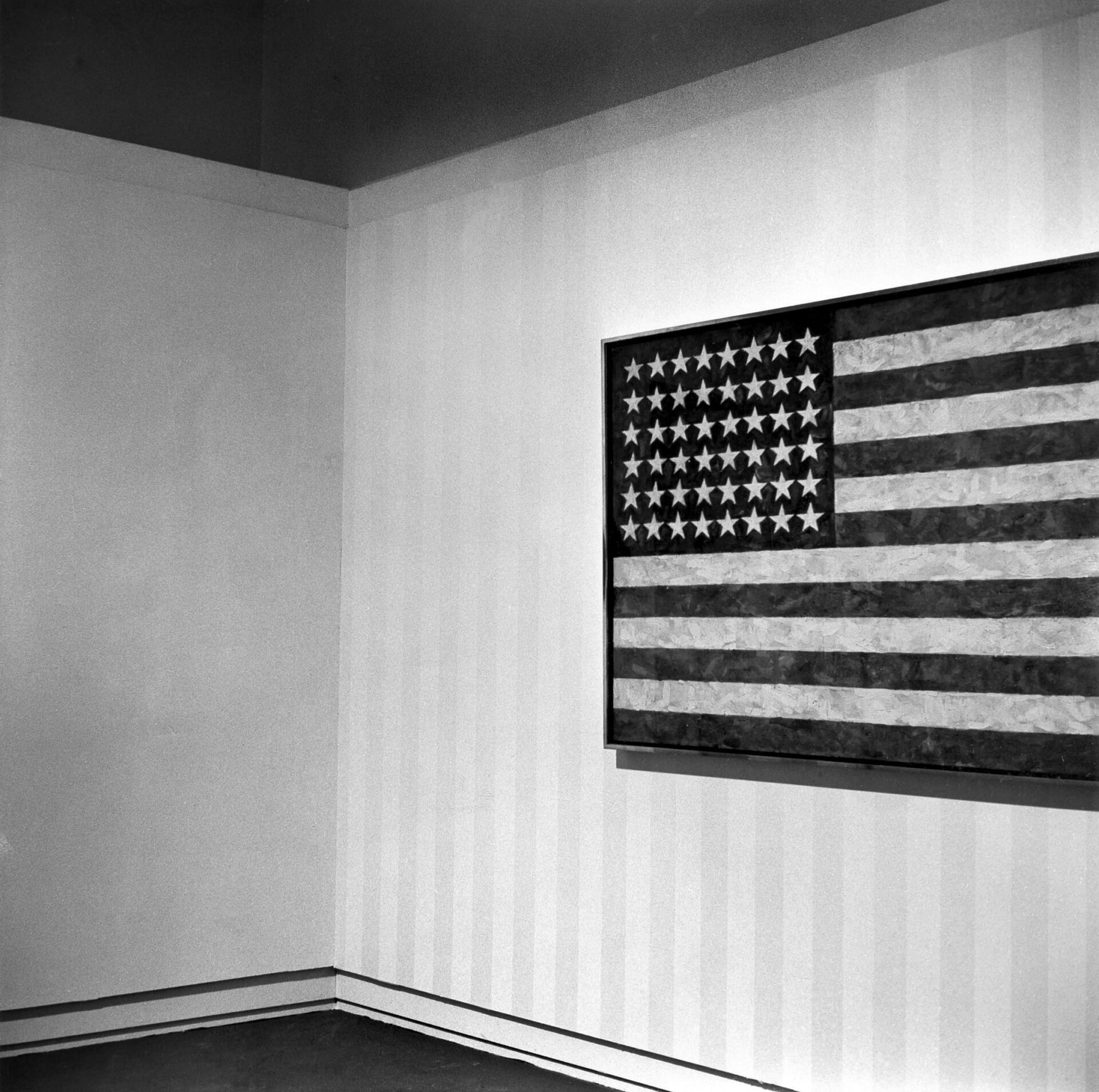

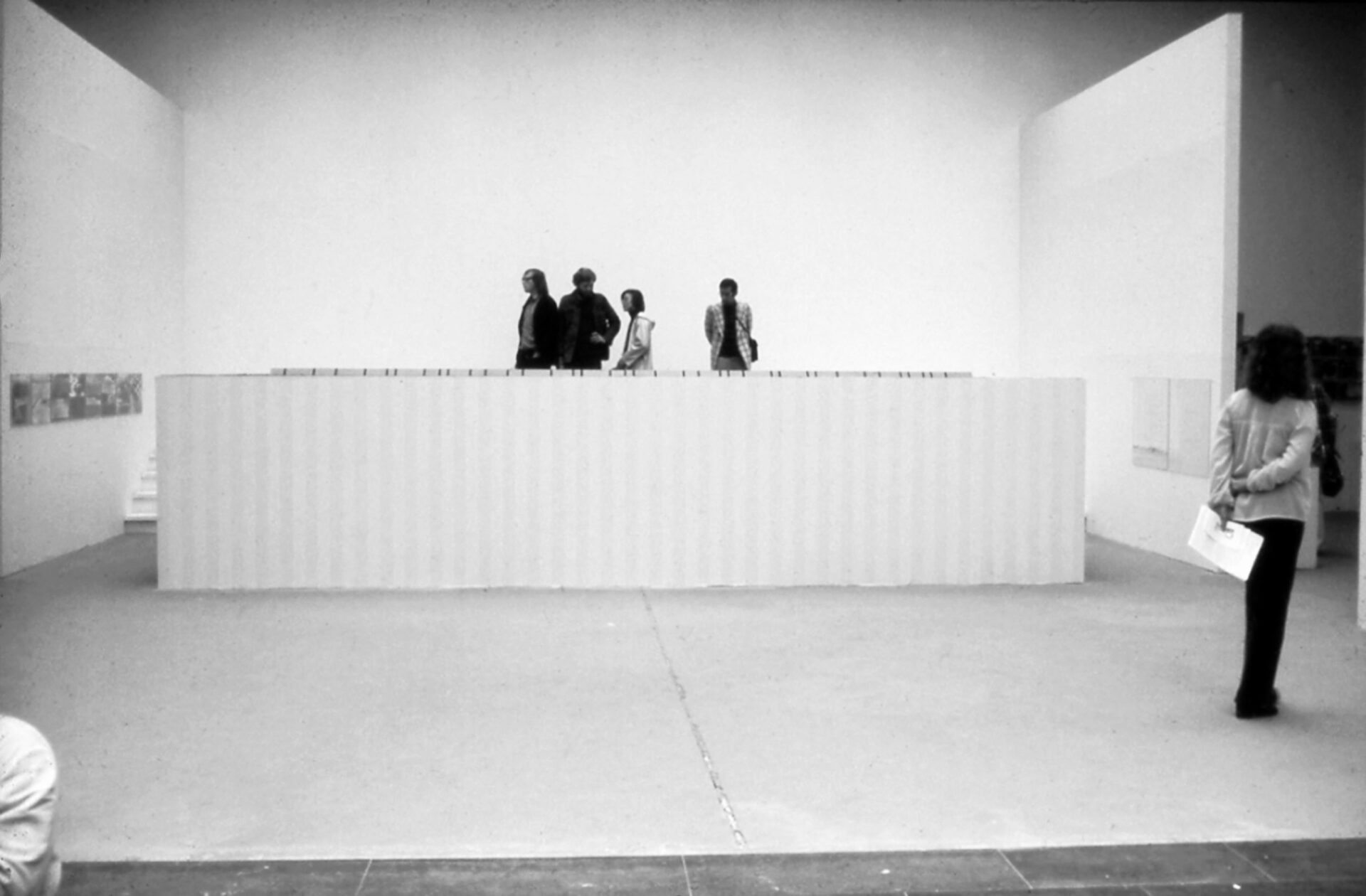

Common sense would bid us to join the critics who denounce the tentacled phenomenon that “curating” has become in recent years, this new “poetic production of reality” that occurs at times against the artists, at times without them (as in the case of the touring exhibition, Curating Degree Zero Archive, entirely devoted to the work of curators and on which Vidokle unleashed his ire). Yet a retrospective look at the history of curating contemporary art invites prudence. Indeed, what strikes me as I go over the debates surrounding the very first exhibitions by Harald Szeemann, the first to have fully assumed the role of auteur d’exposition, isn’t so much the extraordinary power appropriated by the curator over the decades, but the constancy of the arguments put forward to denounce such omnipotence. A quick overview of the writings that Szeemann’s most famous denigrator, Daniel Buren, produced at the turn of the 1960s is enlightening. At Documenta V, Buren observed that “more and more, the subject of the exhibition tends not to be the exhibition of works of art, but the exhibition of the exhibition of works of art…. Here, it is unquestionably the Documenta team, headed by Szeemann, that exhibits both the works and itself to the critics. The presented works are the carefully selected touches of colour in the general tableau composed in each section (hall).”6 6 - Daniel Buren, “Exposition d’une exposition” (1972), in Daniel Buren: les écrits: 1965-1990: Tome 1 (Bordeaux: CAPC Musée d’art contemporain, 1991), 261. By covering the walls of the galleries at Documenta V with striped paper, Buren wished to make the spectator aware that the significance of the works is intimately tied to their exhibition context, and depends, in the end, on the curator’s discretionary power. Buren’s arguments are taken up again thirty-five years later by Anton Vidokle to criticize Roger Buergel, curator of Documenta XII. Vidokle, for instance, writes that arguments for broadening the curator’s role “should not become a justification for the work of curators to supersede the work of artists, nor a reinforcement of authorial claims that render artists and artworks merely actors and props for illustrating curatorial concepts.”7 7 - Anton Vidokle, “Art without artists?,” loc. cit., 1. It is troubling to see that this dual criticism — that curators are authors who sign their work and that this signing supersedes the exhibited works — should remain unchanged throughout the years. Whether one takes the criticism that Douglas Crimp addressed to the curators of the great German and Italian exhibitions of the early 1980s,8 8 - Douglas Crimp, “The Art of Exhibition,” October, No. 30 (Fall 1984): 49-81. that of Yves Michaud regarding the curators of the Centre Pompidou in the late 1980s,9 9 - Yves Michaud, L’Artiste et les commissaires (Nîmes: éd. J. Chambon, 1989). of Bernard Fibicher about Jan Hoet, curator of Documenta IX in 1992,10 10 - Bernard Fibicher, “Les faiseurs d’exposition,” in L’art exposé (Sion: Musée cantonal des beaux-arts, 1995), 271-278. or even Paul Ardenne’s more recent criticism of curators developing in the wake of relational aesthetics,11 11 - Paul Ardenne, “De l’exposition (de l’art) à la surexposition (du commissaire),” L’Art même, (4th trim., 2003), No. 21: 6-9. the argument hasn’t aged: it steadfastly persists in decrying the fact that curators take themselves for artists and make unbridled use of the exhibited artwork to create their own “œuvre.”

Exposition d’une exposition,

une pièce en 7 tableaux (détails | details),

travail in situ, Documenta V, Kassel, 1972

© Daniel Buren / SODRAC (2011).

photos : © DB-ADAGP Paris, permission

de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The constancy of these criticisms prompts me to draw a few conclusions. First, a simple observation: the author-curator that is presented as a recent phenomenon, whether to extol or to excoriate, is in fact a phenomenon as old as contemporary art itself. While curators have certainly gained in professionalism and visibility in the last two decades, their role and their relationship with the artists hasn’t changed, fundamentally. To the Hans Ulrich Obrist adulator who cries out “Curating is now!” one may counter that this “now” has lasted forty years. One must then question the profound motivations for these criticisms and admit that they are rather less concerned with the author-curator than with contemporary art itself. The latter, it turns out, came into being in the late 1960s with what is called the “return to the museum,” embodied precisely in Harald Szeemann’s major exhibitions: When Attitudes Become Form, in 1969, at the Kunsthalle, Bern, and Documenta V in Kassel, in 1972. After the great ideals of the 1960s had failed in reconciling art and life, artists decided to return to the museum. It was at that moment that the notion of “contemporary art” was used for the first time as an aesthetic category by certain European curators. One must therefore admit that contemporary art was an institutional art from the outset. Which is precisely what disturbs contemporary critics of the author-curator. In fact, that is what Ardenne explicitly expressed a few years ago in a text that denounced curators’ overexposure, drawing on Buren’s criticism of Szeemann in the following terms: “In 1972, Daniel Buren thus reproves Harald Szeemann’s ‘mounting’ of Documenta in Kassel, of which he was then guest ‘curator’… More broadly, what the Frenchman is also taking aim at is the beginning of a culture of subjugation governed by the institutionalization of the artistic field. And its inevitable outcome in terms of curatorship.”12 12 - Ibid., 6. But Ardenne fails to see that this institutionalization is in no way a subjugation, but the only means artists found at the time to propose an art with critical effectiveness. Buren himself provides the best example: if his critique of the author-curator stands out, it is because it was uttered within the Documenta institution. Who, at the time, noticed that Buren had gone on to fly-post in the streets of Bern during When Attitudes Become Form (to which Szeemann had not invited him) to condemn works compromised by the institution? Buren, in 1969, still believed that art in the street could simultaneously reveal and denounce strategies of domination to passerby-spectators, something the Buren of 1972 evidently no longer ascribed to. It is indeed one of the paradoxes of contemporary art that its critical effect is inseparable from the institution disseminating it. This criticism is in part made possible thanks to the role of the curator, who, while staging his own subjectivity — his “obsessions,” to use Szeemann’s words — enables the debate and the polemics to take place. It is in the nature of the curator to exhibit him or herself, just as Buren reproached him for in 1972, but to exhibit in both senses of the term: he exhibits himself by expressing his authorial subjectivity through the selection and arrangement of artworks, but he is also exposed, for better or for worse, to the critics by giving a face to the institution. Only on this condition does contemporary art function, when the one responsible for the exhibitions — whether he or she be the museum’s director, its curator, or an independent curator — is fully engaged and openly exhibits his or her aesthetic options. Szeemann (with a few other curators: K. G. Pontus Hulten of Stockholm, Edy de Wilde of Amsterdam, Flor Bex of Antwerp) was one of the first to understand this, as he had occasion to write several times: “It has been shown that those institutions that are most alive are led by people who presume that only their subjectivity will ultimately become the most objective.”13 13 - Harald Szeemann, “Le musée des obsessions” (1974-1979), in Écrire les expositions (Bruxelles: La lettre volée, 1996), 40-41. That, it seems to me, is one of the reasons for which Szeemann, in the history of contemporary art, has now largely eclipsed the figure of Seth Siegelaub, another major curator of the late 1960s, who had organized such exhibitions as Xerox Book, in 1968, and January 5-31, in 1969, which brought together the work of American conceptual artists for the first time. But where Szeemann claimed authorial subjectivity loud and clear, Siegelaub adopted an extreme neutrality, explaining that: “All choices in the predetermination of the exhibition hinder the viewing of the intrinsic value of each work of art.”14 14 - Seth Siegelaub, “On Exhibitions and the World at Large,” Studio International (December, 1969): 202. This myth of the curator’s total transparency could be justified in the context of conceptual art, but we know today that mediators that defend the impartiality and objectivity of their aesthetic choices are very often the ones who become extreme manipulators, or else propose the most insipid events. Faced with such faults, the author-curator’s excess subjectivity seems a venial sin.