Montreal, March 11, 2014

Hi Sylvette,

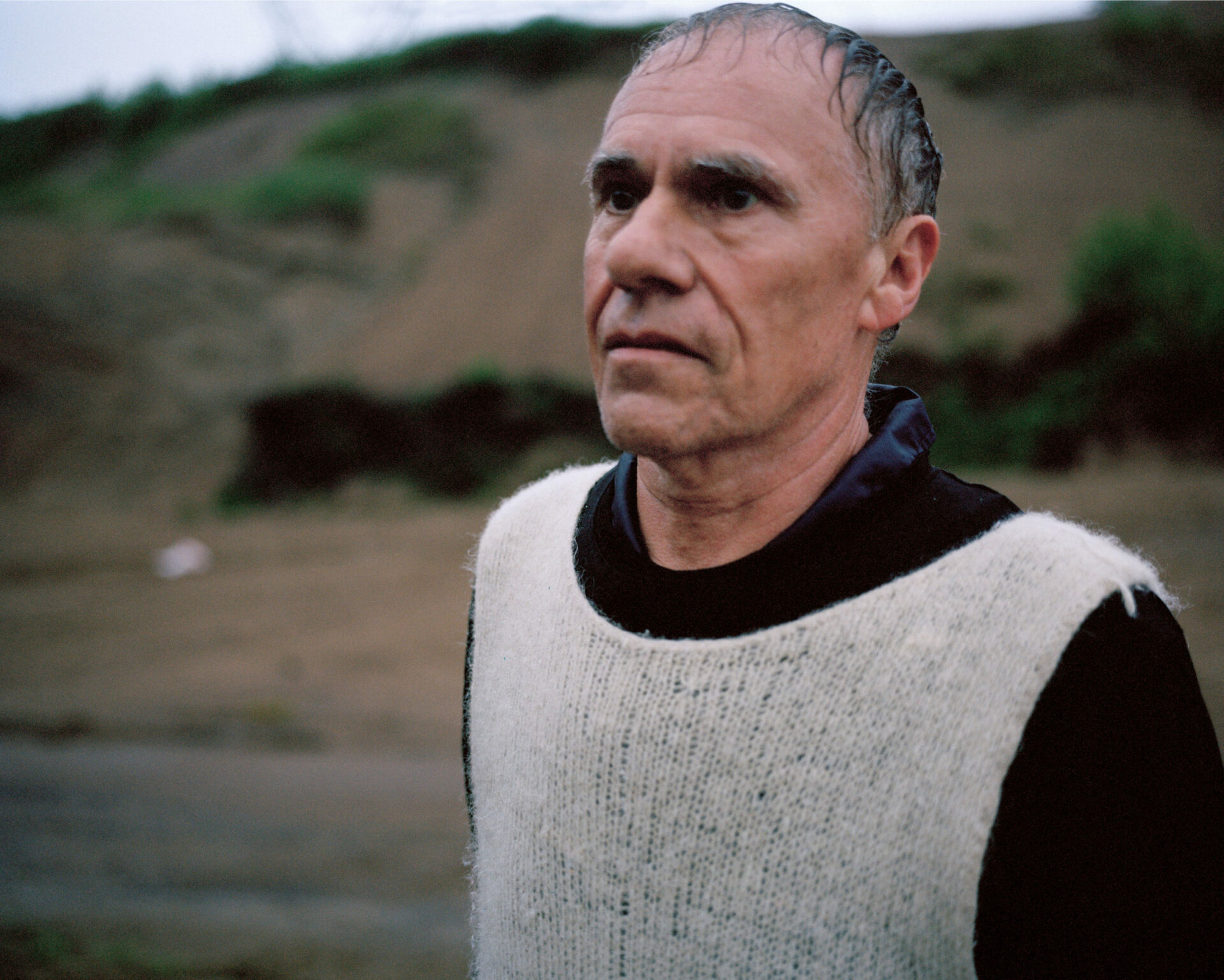

I hope these few words find you in good health. For my part, time races forward, with a plotline that shows no sign of slowing down. To conjure an image, I currently feel like a runner in Parcours, one of Jacynthe Carrier’s video projects exhibited last year at Occurrence. Did you see it? In the grey light of an overcast sky, Carrier filmed a group of people galloping through a sand quarry. The looped sequence is punctuated by breathing spaces. Presence here becomes a flowing current, movement a narrative. Each body is read into the space as a parcel of time, enabling one to gauge its passage. Like the runners, I’m trying to keep up with the group’s pace.

I want to thank you for your generous invitation to contribute to the thirtieth-anniversary issue. I must confess, though, that the idea of carte blanche gave me the jitters, because I know that thought, like history, evolves, and that an entirely different text may “take place” tomorrow. Besides, this issue of the evolutionary seems highly topical in art practices. I’m thinking, among others, of Claire Savoie, whose methodology in Aujourd’hui (date-videos), revolves precisely around this idea. For eight years now, she has been producing one video a day from the visual, audio, and textual materials that each day affords her. From the single thread of her evolving present, she knits together highly poetic sequences, interleaving signs of the times and surrounding motifs.

If, for this open invitation, I were to back up a few steps to try to picture the last decade’s production, I would need to reflect on the works, issues, and approaches that have fuelled my thoughts and research since my generation first joined the voices making up the art field. Obviously, I make no claim to any kind of exhaustiveness, since current practices are as diverse as they are individualized. Consequently, every artist seems to particularize his or her own relationship with time, and it is precisely this aspect that I wish to address. I also think it is appropriate to consider the context in which the new generation practises. esse’s thirtieth anniversary therefore seems to me an opportune moment to reflect on the conditions faced by thirty-somethings today and their relationships with time.

Photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The thirty-something artist was born at the heart of the information revolution, during which technology progressed at a stupefying rate. The present has, in some sense, become the trademark of the consumer society to which she belongs. She uses several means of communication, sees the world as a network, thinks by way of Post-its, and relates to the social fabric through “posts.” She has learned the various forms of language of the “information society” in which the present is ubiquitous. One of her greatest qualities is adaptability. Nomadism is in her DNA.

In her concept of time, as in her love affair with the Polaroid and the concept of immediacy that it conveys, our thirty-something is particularly fond of the idea of responsiveness; much responsiveness, at least, is expected of her. No sooner is it spoken than her speech is disseminated, shared, relayed. Between thinking and saying, time flows swiftly. She was taught that modernity caused a breach in the relationship among past, present, and future, and she sometimes has the feeling that she has fallen into this breach, in the depths of which historical time is stopped. In his Régimes d’historicité: Présentisme et expériences du temps (Paris: Seuil, 2003), François Hartog has insightfully examined this impression that historical time is on hold: “Might we,” he asks, “have passed imperceptibly from a notion of history to one of memory?”

Photo : © Claire Savoie

permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

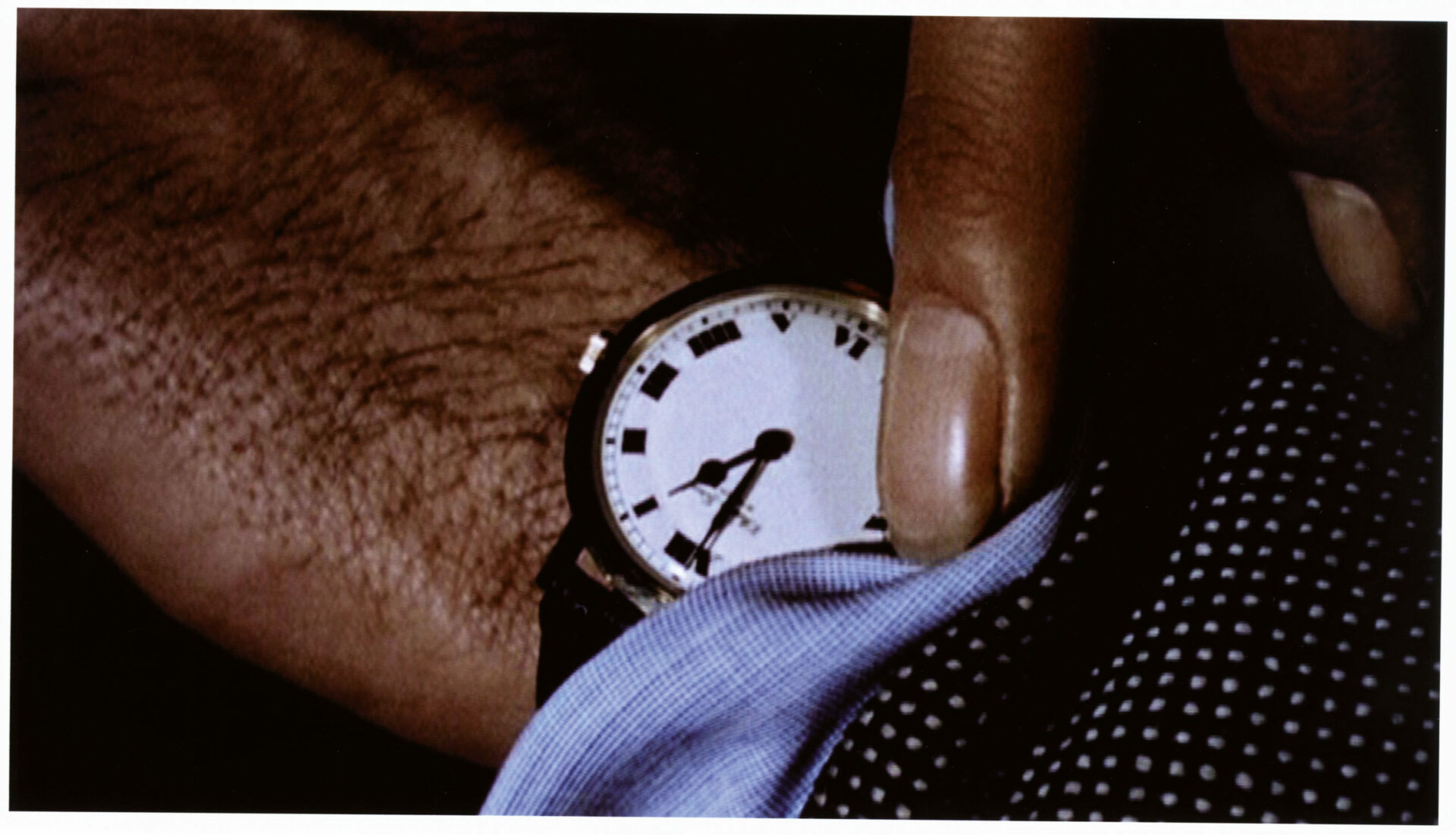

The impoverishment of our historical experience seems intimately bound to the proliferation of sources and modes of communication that keep us riveted to the present. For a historian of my generation, this “presentism” suggests that methodological habits have changed considerably; that the tools of our profession, which allow us near-instantaneous access to information, have an inevitable impact on our historiographic perspective; that now the past is never quite considered past; that it accumulates; that drawing the past out of the present is a way of eliminating the distance that separates them. And while the distance gone is a thing of the past, the motion — and thus the going — is invariably in the present tense. The distance travelled, like the distance yet to go, is thus wholly indivisible. Patrick Bernatchez’s project BW (BlackWatch) seems closely aligned with this notion of a time weaned from its dependence on movement. On the face of a simple, understated watch, with a black horse-leather strap, designed by the artist and produced by watchmaker Roman Winiger, it takes a thousand years for the needle to perform a revolution. Although such a project renders time imperceptible to the human eye, it nonetheless symbolizes a contraction of historical time, because time is in fact performing. . . and we trust that the little hand is moving.

Upon reading Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (Chicago University Press, 1958), the thirty-something will have understood that prior generations had brought about an inversion of contemplation and action. Might this be one reason motivating today’s artists to restore contemplation, the imperceptible, the immaterial, and a certain frugality in their work? Might it be a form of resistance? I ponder the question when I reflect on the body of video work produced by artist Olivia Boudreau. In scenes that can be viewed, among other things, as essays on monotony or variations on household beauty, she manages to generate a direct and concrete experience of time as duration. Sitting in front of Femme allongée, one of her recent video works on display at Concordia University’s Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, I understand that contemporary artists work with time as they would with clay.

vue d’installation | installation view, Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal, 2014.

Photo : Paul Smith, permission de | courtesy of the artist &

Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal

vue d’installation | installation view,

Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal, 2014.

Photo : Paul Litherland, permission de | courtesy of

the artist & Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal

vue d’installation | installation view, Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal, 2014.

Photo : Paul Litherland

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal

New tools afforded by technological development and artists’ frequent use of what I will generally call “machines” in the conception and realization of their work demand of spectators that they reconsider the very definition of materials. In this sense, looking back over the last three decades requires that we reconsider our conception of time, as much from the point of view of representation as from its use as a material. At the turning of a millennium that felt like a shifting of gears, our relationship with time, which had always been connected to our observation, has undergone a profound change — a reflection that few will dispute. Let us, then, consider the new individualized forms.

John Cage’s 4’33”. Robert Filliou and George Brecht’s One Minute Scenario. One Second Sculpture and One Minute Demonstration by Tom Marioni. Erwin Wurm’s One Minute Sculpture. Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho. Michael Snow’s See You Later, and See You Later / Au Revoir: 17 minutes en temps réel by Sophie Bélair Clément.

The last sixty years have seen the appearance of new monumental forms. Precisely because these forms have proliferated, a typology seems naturally to have developed within art production around types of distance and modes of tension: fragmentation, sampling, collage, mixing, contraction, stretching, slow-motion, looping. . . The plethora of essays and exhibitions dealing with these modes of action confirms the relevance of the subject at the heart of current art practices.

In 1964, the year that Andy Warhol produced Empire, conceiving an action filmed — and viewed — in real time was thought audacious. Fifty years later, we are still “experiencing” time differently (I wish to emphasize the active trialling in the word, and its cognate “experiment” — to test something to ascertain its qualities and value). We congregate at the museum to see Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a similar endurance test and a monument to time and the moving image. Made up of thousands of excerpts from films and TV series, this twenty-four-hour long video unfolds time as a sequence of which every minute is arduously edited and illustrated. Here, disparate times accumulate and unfold in real time, giving us a dizzying view of the world through the contraction of more than a century of cinema. It is a new kind of synthesis of time, in which past, present, and future are completely interdependent in a looped construction that may be read as a virtual form of eternity.

capture vidéo | video still, 2010.

Photo : © Christian Marclay

permission de | courtesy of the artist & White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

On the one hand, the conceptual nature of this art reminds us of our presence and our being part of the world. On the other, it confirms that we have a dual relationship with time: through our own stories, and through history. While a story’s memory is linked to its personification, history requires a distantiation. Logically, the more accessible the individual stories (and the greater our interest in them), the more seemingly unattainable our collective articulation of history. I currently have the impression that the active memory in our collective awareness is almost wholly saturated, monopolized by the stories of the moment, and that our territory is a shrinking time-space. I know that I am not alone in having these thoughts; so, when shall we see a “Department of Time and Tempo,” as Paul Virilio proposed?

“The world has been enriched by new beauty, the beauty of speed,” the Futurists said in their manifesto of 1909. While our generation turned away from the ideological implications of the Futurists, it seems to have fully embraced this new measure of an evolutionary relationship with time. A century has passed since the writing of that manifesto, and it seems to me that we are articulating yesterday’s future in the present tense.

Such are my ongoing preoccupations, then. Thank you for taking the time to read me through. And, oh, happy birthday, esse!

Marie-Eve Beaupré

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]