Laying a Hand on a Thigh. And Doing Nothing More.

Photo : Sandra Lynn Belanger, courtesy of the artist

The painter does not paint on an empty canvas, nor does the writer write on a blank page, but the page or canvas is already so loaded with pre-existing, pre-established clichés that it is first necessary to erase, clean, flatten, or even shred in order to let in a breath of air from the chaos that brings us vision.1 1 - Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What is Philosophy?, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 204.

Situated at the intersection of theatre, dance, and circus, Nicolas Cantin sees the black box as a virgin canvas. Extremely visual, his works stage objects, among them, the body. Clean and minimal, and more bastard than hybrid, his pieces tend to construct performance as a kind of moving tableau. More a dramaturge of time and space than a creator of movement, he above all foregrounds the “living”: “I’m interested in the intimate. More than anything, I like to look at people who are unaware they are being observed. I like to witness that instant in which acting ceases. When I look at you, it’s like observing a deer in the middle of the forest. Victory is a magnificent thing, but, strangely, there is something even more moving in the spectacle of defeat. There is beauty in the image of a boat run aground. I’m at the beginning of something. Today, all that interests me is seeing people on stage in the simplest of ways, people who allow our gaze to fall on them. And I think that that is already a great deal.”2 2 - Nicolas Cantin, presentation text for Grand singe (2009) (Own translation).

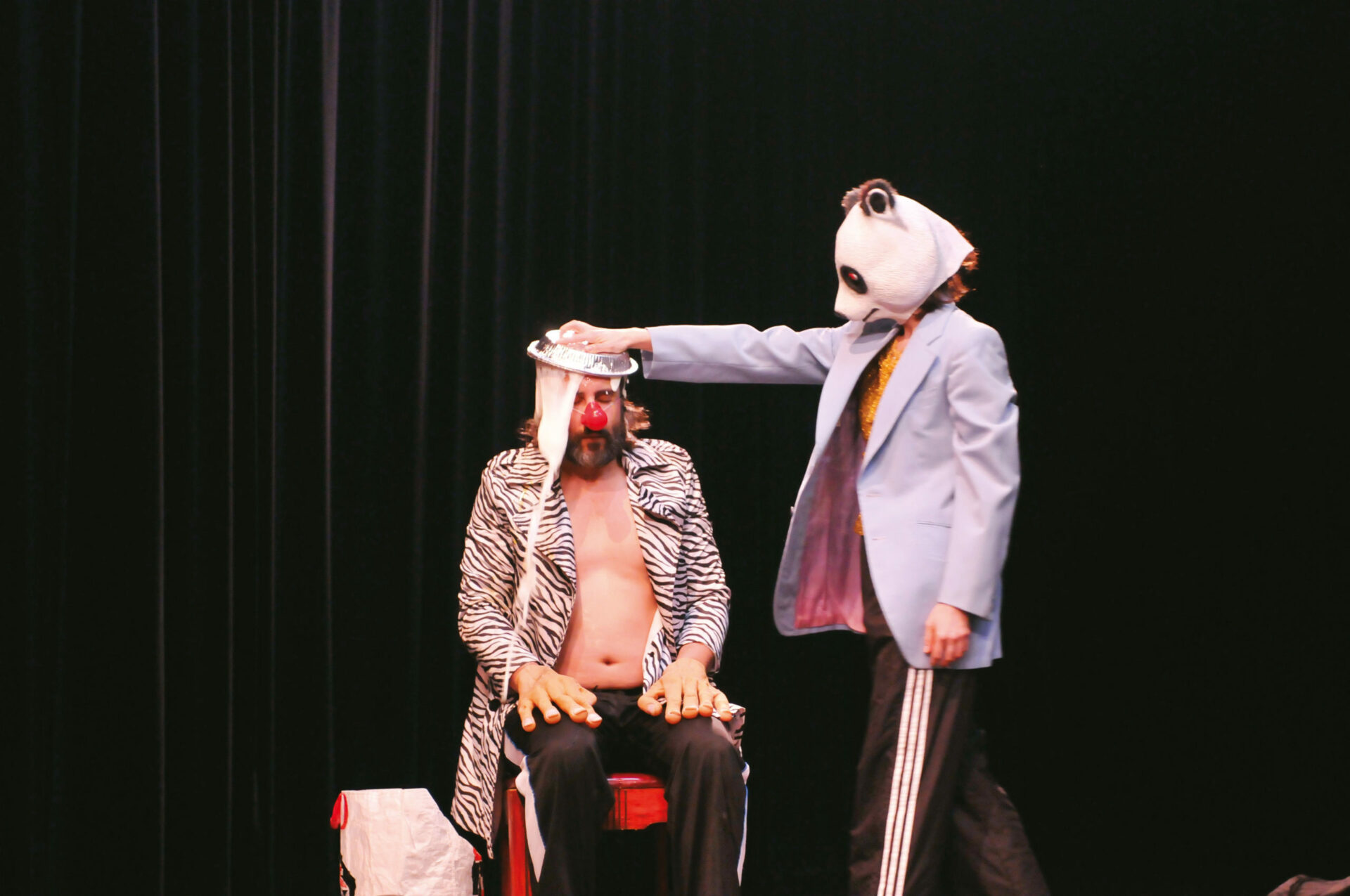

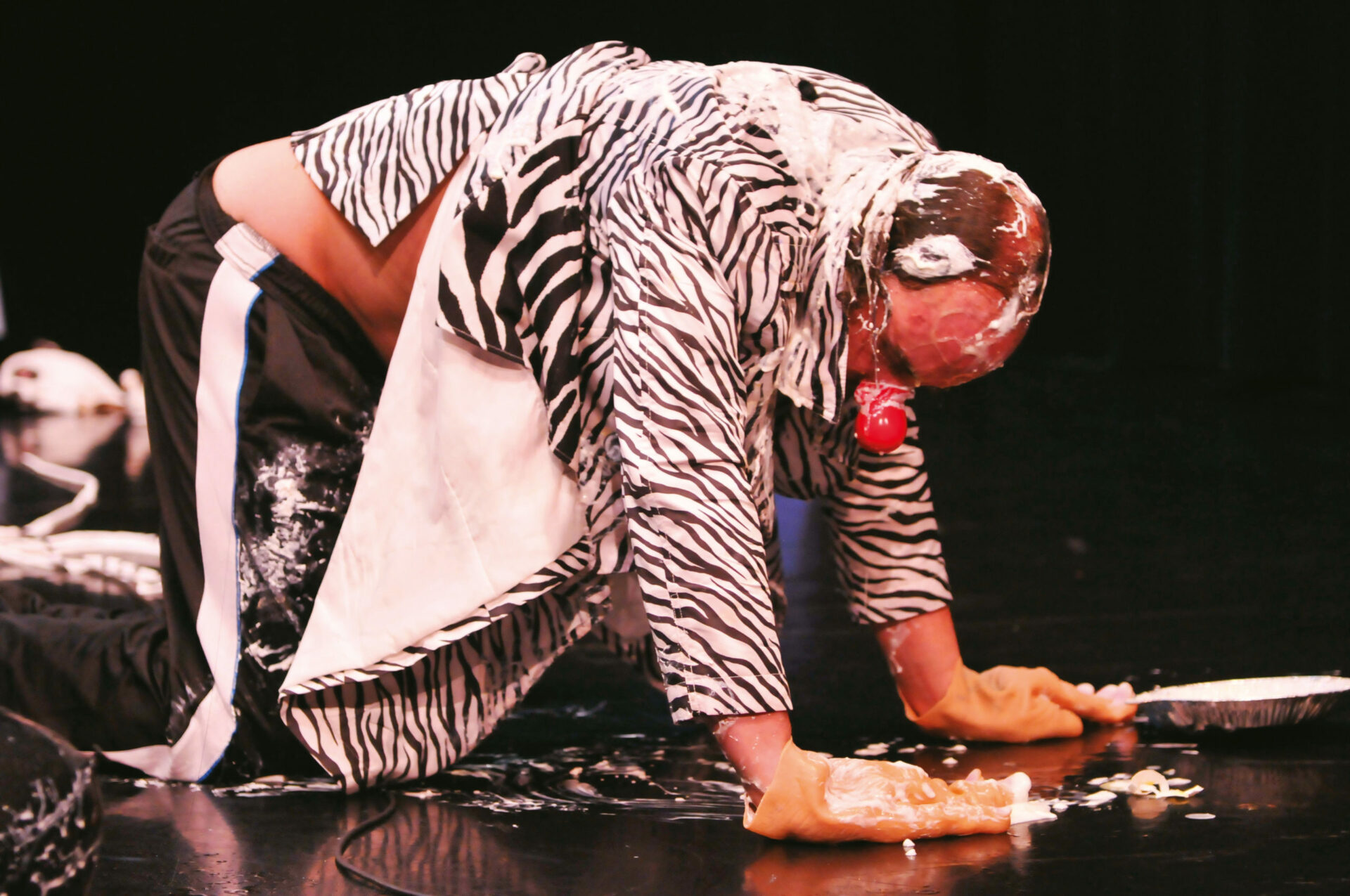

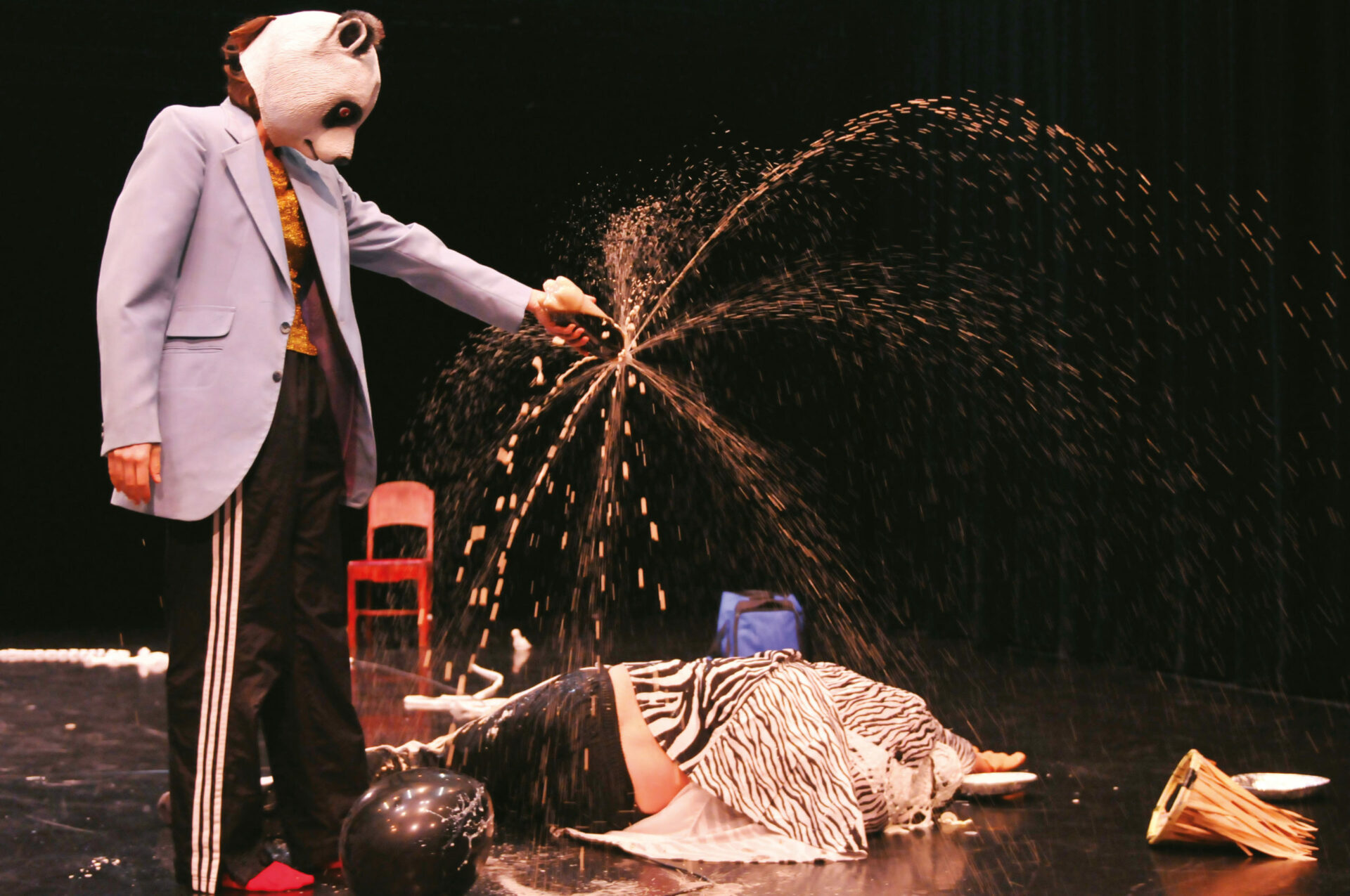

Grand singe, 2009.

Photo : Simon Couturier, courtesy of the artist

Black Clown

Katya Montaignac : In Grand singe (2009), a man and a woman share the stage. Despite themselves, they personify a couple. . . And yet this duo (like those to follow) depicts two people who simply cross paths. Without fuss. Anne Thériault’s surges of affection are systematically thwarted in face of a partner who remains as impassive as a wall, stripped of the slightest emotion. This absence of reaction constitutes the real drama of the piece.

Their actions repeat like an infernal routine. Disengaging the actors from their performance allows more space for “being” on stage: “being present on the set as if one were sitting in one’s own living room” (Jérôme Bel). This lack of projection creates a state of presence, which in turn permits the “living” to erupt on stage. When Stéphane Gladyszewski stops, Anne absurdly continues without him. The scene thus shifts dramatically, with the comic taking a tragic turn.

Finally, the piece draws to a close in unsettling ambiguity: the near-Edenic couple (childlike, naïve, and innocent) smear their bodies in black paint, conjuring the idea of eternal sin, with the stage evocative of a playground in ruins.

Blank Page

Nicolas Cantin : An encounter is what Grand singe is for me. An encounter between Anne and Stéphane. An encounter between actors and audience. And an encounter, perhaps, between the actors and the show itself. The show obviously being the mask behind which I hide.

And all of this occurs through the performance. The performance to which the actors give themselves is simple — primary — and has a rudimentary alphabet; a performance that does not deceive but that slowly slides towards the tragic. In other words, in Grand singe, we see two people who will be taken in by their own performance and be swallowed by the spectacle itself.

I’m glad that you mentioned the eruption of the “living” on stage. I think this is what I’m obsessively seeking in everything I do. When I started work on Grand singe, I began with a blank page. This blank page was an empty space in which two people (in this case a man and a woman) would have to exist. The show began from this simple starting point. My aim was to make something exist on stage with only the bare essentials. By reducing the spectacle to its simplest form, I hoped that the emptiness would act as a showcase (or as an enlightener) for Anne and Stéphane. It was like emptying a house of furniture; suddenly, by opening up the space, by freeing it of encumbrances, I simultaneously opened my gaze, and thus that of the audience.

The Eruption of the Living

KM : The eruption of the living on stage consists, paradoxically, of emptying rather than filling the space: of quite simply allowing an action to live on stage and giving it time to breathe. Quite the reverse of constructing or building up, it is rather a question of taking away, undoing, extracting, detaching, stepping back: of allowing things to come to pass on their own by granting them “time” (installation time is important, hence the idea of an effect). Then, sometimes, something of the “living” will suddenly materialize on stage, escaping from the spectacle, while establishing it at the same time.

For this to happen, one must create a frame, a space, and temporality, rather than a tangible representation. For example, one of the actions in Grand singe consists of laying a hand on a thigh. And doing nothing more. Its duration suggests more than it “represents.” This may seem simple and abstract, or altogether anodyne and ordinary, yet the situation raises all sorts of interpretations. The choice not to explain (or clarify) the gesture allows for a range of possible meanings to proliferate. The situation thus becomes an enigma to be solved by the imagination of each individual. This requires active observation on the part of the audience, a readiness to fill in the holes, furrows, and voids for themselves.

The Unnamed

NC : Laying a hand on a thigh. And doing nothing more.

This sums up quite well what I’m trying to do.

Laying a Hand on a Thigh. And Doing Nothing More.

I think this phrase encapsulates my whole project. Capturing the living. I’m almost ashamed to say it, given the impossibility of the project to which I’ve dedicated myself. But that’s what makes it beautiful — and moving at the same time. My work is in some ways a return to prehistory. To what was there before history. I like the idea of returning to something raw, archaic. To something unnamed. That’s the project.

Gaping Absence

KM : Belle manière (2011): again a man and a woman, again the absence of a relationship. Each of them acts without an awareness of the other. The figure of the duo thus splits in an aesthetic of rupture, disequilibrium, and collapse. The stage becomes a place of chaos in which actions resonate in the void. They have no echo, no solution. The actions are performed without purpose. The absence of logic and resolution simultaneously lend the play a comical, moving, and profoundly tragic aspect.

Ashlea Watkin thrashes about and sings call-and-response songs. Without response. Normand Marcy’s presence resonates like a void, an absence. A gaping absence. Is the presence of an absent being not worse than absence itself? He is both there and absent at the same time. He sees but perceives nothing. The opposite of a Prince Charming: heavy, static, clumsy, shady, lost. He does nothing, trying neither to act nor respond. He is merely there, as if he’d been set down on stage along with the other objects. He is there but could be anywhere else. The world revolves around him without any reaction on his part. He absorbs. Above all, he reflects a state: of being rather than doing. Being there, but doing nothing.

Belle manière, 2011.

Photos : Sandra Lynn Bélanger, courtesy of the artist

Solitudes

NC : I never work with the idea of the duo (for Grand singe or for Belle manière) or the quartet (for Mygale). I prefer the idea of working with people. To my mind, thinking of addition (1+1 or 1+1+1+1) rather than of two or four makes all the difference.

I work with solitudes. Solitudes that I put together. For me, this is what we are in real life. It makes me think of the phrase two parallel lines meet in infinity. It is the space between two people that nourishes the encounter. And it is the space between two people that interests me. It is the primary space. It makes me think, makes me question myself. When you look closely at two very different photos placed side by side, your imagination not only begins to create all kinds of associations between them, but also, miraculously, to produce other images based on them. That’s what I try to do by means of living material.

As for the relationship, I don’t like forcing it. In my plays, one sees people who don’t seem to act together. They are strangers to one another in some ways. But for me it’s about an encounter, even if the encounter doesn’t take place according to established codes. There is something resembling the connection that might exist among a family of tigers. Seemingly indifferent to each other, but together. Escaping the codes, our human codes.

The Trouble with the Intimate

KM : Rather than creating bonds, your creatures seem to meet without noticing each other. At the same time, paradoxically, this absence of relationship actually creates one: a strange relationship, shaky, even dysfunctional. When you speak of an encounter, I believe it takes place between the public and the characters, rather than among the characters themselves. In fact, it is the spectators who fill in the holes with their imaginations, who create a connection, a space, a “being together” between themselves and the performance.

It seems to me that a new element is appearing in your work in the form of a secret (whether real or fictive) delivered on stage. This brings the notion of intimacy to the stage in a different way. In Mygale (2012), the performer’s detachment makes his testimony even more poignant. A kind of unbearable lightness of being. . .

In the end, you erase all traces of heroism, which makes the actors endearing, vulnerable, laughable, and tragic at the same time. And you stretch time so that the audience practically shares the experience of the characters’ daily lives, thus becoming part of their intimacy. In this way, for the time of the performance, the viewer seems to live together with the characters.

A Voice

NC : There are no creatures.

There are no characters.

There are people.

I insist on this notion of people.

You’re right when you say that a new element is appearing in my work. At the end of Mygale, there’s a recording that everyone — the actors on stage and the audience — listens to. It’s how the show ends. With someone talking about love. I like the idea that all that’s left on stage at the end is this person speaking through a radio-cassette player. Nothing but a voice. I’m moving into new territory here. Recording intimacy. In my past work, this intimacy was expressed through the body. Now it passes through language. And it’s true that this takes the path of a confession.

For a while now, I’ve been asking myself new questions. How to put what happens inside into words? How to record fragments of a person’s intimate life in words? With Michèle Febvre,3 3 - Nicolas Cantin worked with Michèle Febvre as part of an intergenerational laboratory created and directed by Katya Montaignac. This meeting gave rise to a solo piece that will be presented at the end of 2013. I chose to dig into her past. By working through the little girl she once was and by recording and reactivating a living memory, I connected with a vital discourse that draws from the same source.

In this work, I wasn’t looking for reasonable language (the idea isn’t to make a library speak, nor to make theatre). Instead, I was looking for subtle language that could make itself heard at the heart of what is most intimate, most necessary to express.

Mygale, 2012.

Photos : Rodolphe Gonzales & Alexandre Pilon-Guay, courtesy of the artist

No more acting?

KM : In Mygale, Peter James seems not to act, to act no more, to have stopped acting. Through a kind of raw presence, free of projection, the slightest (micro)movement takes on incredible importance. For example, standing on stage in a natural way. When Peter stands, with his back to the audience, a quasi-sublime sensation stirs in us, making us feel that we aren’t really there (despite being in the theatre. . .). I like to see people standing naturally on stage, just as one stands in ordinary life, without stiffening the back or flexing the muscles, without “neutralizing” one’s posture like many contemporary dancers who — at worst — do so almost naturally they have been “trained” so much. Nevertheless. . . can we really put people on stage as they really are, without them fatally becoming “characters?” Does the mere fact of being on stage not make a travesty of presence? Is this the projection of my fantasy as a viewer? Hence, perhaps, the very peak of theatre, its limit (or wager) lies somewhere between the true and the false, between the effect of the real and the credible.

Illness

NC : I have a special fondness for Mygale. For me, this play diverges from my earlier work. In a sense, it is a continuation, as (I think) it goes further, more deeply — more radically, more explicitly — into intimacy. I think it resembles me. In some ways, I’m happy this play divides people. With Mygale, I pushed back the limits. My limits. I put myself in a place I hadn’t been before: I wasn’t looking to be loved. I think each of my plays is a failure. That’s what makes the work passionate. Fragile. Delicate. And strong.

At some point, one has to come to terms with the public (with its expectations — its gaze) in order to dive into something new. I see this imperfect thing I create, the thing we call a show, as an illness. And this illness doesn’t ask permission to exist. It takes the space it needs. It acts by reacting to its environment. For me, every illness is a reaction to a lack of love. And if one can say the same thing of a show, I think a powerful poetic vision reveals itself to us.

Translated from the French by Peter Dubé