In recent years a growing number of artists engaged in conceptual and performative practices have used the exhibition as both a stage and as a medium to explore their relationship to the archives of their own histories. In other words, they loop art’s own past through the reproducibility of its own presence while acknowledging its increasing self-institutionalization. Artists as well as choreographers (amongst others, Ai Arakawa, Pablo Bronstein, Gerard Byrne, Boris Charmatz, Lynda Gaudreau, Andrea Geyer, Sharon Hayes, Luis Jacob, Xavier Leroy, Sarah Michelson, Paulina Olowska, Sarah Pierce, and Emily Roysdon) who share this interest use the exhibition as a format to investigate the politics of the ephemeral and its physical manifestation as a time-based mode of production rather than a fleeting state of being. Through their performances, choreography, visual recordings, lectures, writing, and installations they actively reflect on the media-based dynamics of these supposedly “dematerialized” art forms, which are in fact often image- and object-based, exploring the chronological layering of the exhibition itself as a performative medium, and relentlessly reading and translating their sources through the framework of the exhibition1 1 - The majority of these artists do not consider themselves performance artists in the classical sense but have adopted performance-based and relational practices as an essential part of their artistic vocabulary, while the above-mentioned choreographers, such as Michelson, Leroy, Gaudreau, Charmatz, and Bel amongst others, are increasingly using the exhibition space as a site-specific space for choreographic exploration, translating choreography into the exhibition.. Their works interweave and counter-read various historical threads, from institutional critique and appropriation art to relational aesthetics and the revival of performance.

Breaking down the fourth wall of performance art’s histories

Two emblematic examples of this mode of production are the work of Brussels- and Berlin-based French artist Jimmy Robert and the Montreal-based, Québécois-Canadian artists Sophie Bélair Clément and her collaborator, choreographer and dancer Marie Claire Forté. Their recent projects, Draw the Line (2013) by Robert, commissioned by the Power Plant in Toronto in the summer of 2013, and Bélair Clément’s 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1) examine the parallel notions of the curatorial and the performative in different yet corresponding ways. Clément, in turn, invited Forté to develop a work for her exhibition at Artexte in the fall of 2012 and winter of 2013.2 2 - 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1)was a site specific installation and event curated by Eduardo Ralickas at Artexte, on view from September 27, 2012 until January 26, 2013. The title also included the following footnote: (1) “General floor plan for Gallery. 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary, phone, desk, file cabinet and catalog. The other has 2 works of each artist.” Seth Siegelaub, guestbook pages and follow-up notes, I.A.43, “January 5-31, 1969” [The “January Show”], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. See http://artexte.ca/sophie-belair-clement2-rooms-equal-size-1-empty-with-secretary1/ (consulted February 27, 2014) They literally break down the fourth wall of the exhibition as a performative space.

While Robert plays out the parallels and de-synchronicities as a mise en abîme of the correlative relationship of performance art to its image-based and archival status,3 3 - Jessica Santone, “Marina Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces: Critical Documentation Strategies for Preserving Art’s History,” Leonardo 41, no. 2 (2008): 147. Bélair Clément addresses how the historiography of conceptual art through its exhibitions, as both its own plinth and stage, thrives in the tension field of its overlapping self-referentiality and its various inherent realities.

The entwining of the conceptual and the performative as a critical mode of investigation is at the core of Bélair Clément’s collaborative curatorial approach in 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1). The historical starting point of the project was Seth Siegelaub’s infamous 1969 MoMA show, January 5 – 31, which featured the work of Robert Barry, Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, and Douglas Hubler. Equally important is Bélair Clément’s decision to curate and to extend an invitation to a series of collaborators and colleagues to participate in the project.4 4 - Most recently in the exhibition Anarchisme sans adjective, sur le travail de Christopher D’Arcangelo, 1975-1979, September 4 – October 26, 2013 at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, Concordia University, Montreal.

2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary(1), installation views, Artexte, Montréal, 2012.

Photos : Paul Litherland, courtesy of Artexte, Montréal

As a result of her extensive research, the artist found various text documents, a floor plan of the show, sketches, a guest book, invitations, several photographs, and a catalogue, as well as written correspondence from both the past and the present.5 5 - Bélair Clément conducted her research at various archives and libraries in North America and Europe, including the MoMA library in New York and the archives of the Generali Foundation in Vienna. To obtain more information the curator of the project, Eduardo Ralickas, contacted Siegelaub, while Bélair Clément started a correspondence with Adrian Piper, specifically in regard to a black and white photograph Siegelaub took of Piper in 1969, which Bélair Clément had found during her research for the project. The image depicts Piper at work, sitting behind an office desk in Siegelaub’s gallery, ignoring the camera.6 6 - See also the curator’s statement: Eduardo Ralickas, Énoncé du commissaire genre: récit historique, avec notes*, 2012, n.p., http://artexte.ca/wp-content/uploads/commissaire.pdf accessed February 27, 2014.

Bélair Clément used this specific image as a curatorial dispositive for 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1), reconstructing a selection of the office furniture and objects depicted in the photograph in Artexte’s exhibition space. She, amongst others, asked the designer and artist Raphaël Huppé Alvarez to reconstruct some of the furniture in the photograph with a high-gloss white resin finish that covered the top surface of the desk, sealing everything upon it, such as books and an ashtray. Several elements of her research became curatorial footnotes, mirroring the original but in a slightly distorted manner: Clément asked the receptionist at Artexte to keep a copy of the infamous photograph of Piper nearby so it could be shown to visitors to better explain the show.

One of the key conceptual decisions Bélair Clément took was to invite Forté to read a three-page text written on a typewriter by Piper in 1969 for a new recording of the work. Bélair Clément received Piper’s permission to record and use this work, originally titled text of a piece for Larry Wiener 1/14/1969, as a script for her exhibition project. The work is based on a sequence of numbers that infinitely breaks down the length of the recording itself — 15 minutes — by half: “The length of this single recorded section is approximately 15 minutes. Or, the length of these two recorded sections is approximately 7 minutes, 30 seconds each. Or, the length of these four recorded sections is approximately 3 minutes, 45 seconds each. . . . The length of these 83.727.602,664 recorded sections is approximately .00000000001071487698475085949775103784890625 seconds each. Or, etc.”7 7 - According to Bélair Clément, Piper, falsely, as she later realized and told Bélair Clément, dedicated the work to Weiner as a gesture of appreciation for helping her find the job as a gallery assistant at the “January show,” (Correspondence with the artist February 5, 2014.) This anecdotal retelling of details and fragments of correspondence are part of Bélair Clément’s meticulous research methodology and conscious insertion as a chronicler into the historiography of the past networks she researches.

In dialogue with Bélair Clément, Forté decided to present “her performative choreographic practice, a continuous show, a searching for inscription in the physical space of Artexte amongst the working bodies of the building and the neighbourhood”8 8 - See the project description published on the website http://artexte.ca/sophie-belair-clement2-rooms-equal-size-1-empty-with-secretary1/, accessed February 27, 2014. and to use the sound recording as a structure for a site-specific choreography to be performed in the exhibition.9 9 - Email correspondence with the author, February 5, 2014.

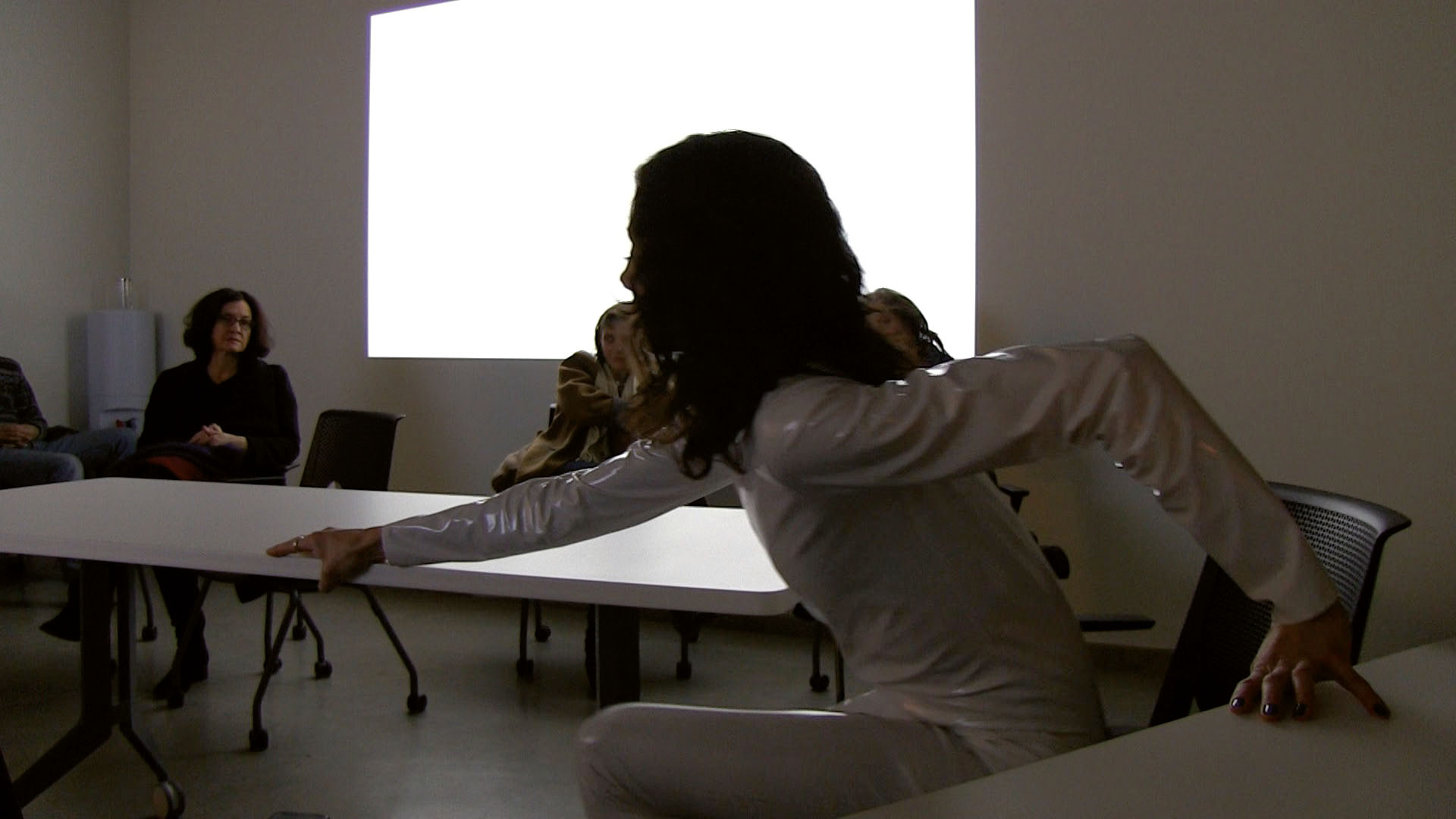

Spectacle continuel, video stills, Artexte, 2012.

Photos: © Marie Claire Forté

Forté’s work resulted in an hour-long performance titled Continuous Show / Spectacle continuel in the small conference room at Artexte. Dressed in a white vinyl catsuit, Forté slowly moved throughout the space.10 10 - The choice to have the objects in the exhibition, as well as Forté’s catsuit, in a glossy finish, is, according to Bélair Clément, a visual reference to the glossy finish of the photographs she found at the MoMA library. Email correspondence with the author, 5 February 2014. Mimicking the movements she observed from the window looking down on the staff of the Cleopatra club across the street, she follows a series of poses and movements that in their precision are in accordance with Piper’s calculations. After this segment, Forté proceeds to slowly push the table and office furniture in a seemingly random manner, gently driving the spectators out of her path. During this flow of poses and gestures she begins her simultaneous translation of the English recording of her own voice reading Piper’s script of numbers — which plays from a small recording device placed on the table — into French. The doubling of her words in two different languages is echoed in the interrelated choices of materiality of the office furniture, the curtain, and a cell phone, as well as the immateriality of the subjects at play: Piper’s script as a sound piece, the concept of the exhibition, and the presence of Forté’s mastery of minimalist yet charged bodily movements accompanied by her seemingly effortless play of voices.

The idea of artistic labour translated into a performative gesture, whether that of Piper sitting behind her desk or Forté’s efforts of simultaneous translation in Continuous Show / Spectacle continuel, offers insight into the invisible social relations of the art world. Articulated within the constraints of the exhibition, these networks become contingent entities and objects of their own: from a documentary source to a performable script and prop to an artefact, to, in the end, an object-subject relationship embodied through Forté’s presence, movements, and voice as much as through the smooth lacquered white surfaces of the three-dimensional reproduction of the coffee table, including books and ashtrays, that are replicas of Siegelaub’s gallery inventory.

This visibility of various modes of translation, oscillating between the curatorial, the historical, and the performative also plays a vital role in Robert’s exhibition Draw the Line. His appropriations and nonlinear readings of canonical works of performance history11 11 - Robert’s appropriations include Yvonne Rainer’s seminal 1966 postmodern dance, Trio A, from 1966, performed with Ian White in Six Things We Couldn’t Do, But Can Do Now (2004); Yoko Ono’s seminal Cut Piece (1964) for his performance Figure de style (2008), Robert Morris and Carolee Schneemann’s Site (1964) for the performance series Counter-relief (2008 – 2012). have led Robert to use the exhibition not as a stage but as a process-based event that allows him to question the complex relationship between the genealogies of the feminist practices he references.

This interest in performance’s contingent relationship of the image and the body, a relationship that is symptomatic of the multitude of changing histories a performance can entertain, is at the core of one of his more recent text-based and site-specific installation projects, which he executed last summer in Toronto at the Power Plant. Draw the Line is based on Carolee Schneemann’s iconic performance and multi-media installation Up to and Including Her Limits (1973 – 1976), which consists of multiple elements: a performance, an installation, a series of well-known photographs, and for Robert, who wanted to use the work “as a starting point to do something else,”12 12 - Draw the Line was a project curated by Julia Paoli. For more information see the upcoming exhibition catalogue Jimmy Robert, Draw the Line, dir. Julia Paoli, Power Plant, Toronto, 2014. most importantly, a manifesto written by Schneemann in conjunction with the piece at the time.

Draw the Line consists of a number of interrelated elements: a text based on the writing of Schneemann, to be exposed, recited, and left in the space; an architectural intervention that flooded the space with natural daylight; a stack of take-away posters produced for the exhibition announcing a performance; a collaborative drawing collage based on a photograph of Schneemann’s Up to and Including Her Limits, which he produced with Glasgow-based artist Kate Davis in 2010; a sound recording of the artist writing in pencil on a smooth surface; and a roll of large photographic paper distributed in the exhibition space. The paper was used as a sculptural prop for a performance Robert scheduled a week after the opening. Dressed in dark clothes, he slowly carried the roll of large photographic paper through the space, eventually unrolling and taping it to the floor. Robert executed a series of choreographed movement and poses while reciting a text based on Schneemann’s writing.13 13 - Ibid.

Jimmy Robert: Draw the Line, exhibition views, The Power Plant, Toronto, 2013.

Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of The Power Plant, Toronto

Both the exhibition and the performance of Draw the Line can be read as a poem, seen as an image of a script, or heard as a score. Robert “moves into the text and image”14 14 - Conversation between the author and the artist, May, 2013. he has chosen and created, using both speech and movement. Schneemann’s feminist critique of painting’s canonization and inherent relationship to indexicality as a male gesture is, both figuratively and conceptually, translated into the present tense of Draw the Line. Schneemann’s constrained horizontal markings are lifted off her entrapped vertical body, liberated back into the three-dimensional. Schneemann’s reaching of her outer limits becomes the script for the choreography of Robert’s drawing body. As Robert takes control of his own limits, creating an equilibrium between body, history, and space, he not only pays homage to Schneemann’s past achievements but specifically sheds light on her belated recognition and institutionalization.15 15 - Helen Molesworth, “How to Install Art as a Feminist,” Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art, ed. Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz, (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 507. His physical marking of the Power Plant’s architecture and the exhibition layout stand for the expression of a thought, a physical and temporal mark within the context of social networks and discourses that determine the constantly changing representational codes of gender within our cultural surroundings.

Robert explores gender and ethnicity as a socially relational category within a historical analysis of the present. He inherently exposes the politics of performance’s role in art history read through the economy of his own presence and contemporaneity. He, through his presence, questions the claim of his movement’s ephemeral nature as a construct that continues to complicate and hinder critical performative practices, specifically hetero-normative standards, from entering the canon of art history.

Both Robert’s work and Bélair Clément’s collaboration with Forté are stagings of an act in which the body negotiates its constant becoming and unravelling as an image within the format of the exhibition. In both practices the space and time of the exhibition become relational elements, constituted and perceivable in their relationships to the objects and subjects that are displayed within them. It is important to note though that neither of them use the performing body as a means to interact with the visitor, nor as a durational, ontologically driven authentic experience parachuted, so to say, from life into the exhibition space. Their aim is to use the body as an active agent that is capable of deconstructing his or her role of participation in the inevitable processes of valorization fundamental to the act of exhibiting art and the writing of dominant cultural narratives.16 16 - Dorothea von Hantelmann, How To Do Things with Art, documents, ed. Lionel Bovier and Xavier Douroux, (Zurich: JRP| Ringer & Presses du reel, 2010), 10.

Both examples allow us to bear witness to numerous art historical references17 17 - This dominant lineage of art history I am associating with Robert’s historical research and counter-reading could begin with Yves Klein, Bruce Naumann, Chris Burden, Allan Kaprow, Fluxus, Otto Muehl, Vito Acconci, and Guy de Cointet, up to Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley. that not only chronologically precede, but more importantly, also legitimately reverberate into the present the struggle embedded within Schneemann’s and Piper’s acts from the past. Robert, Bélair Clément, and Forté allow us to recontextualize historical works, as well as the documents they have produced, within the agency of the presence embodied in the exhibition space.

Seen in relation to the institutional politics they are confronted with as artists who engage in both the conceptual and the performative, both treat the exhibition as a temporal as well as spatial entity, a surface to draw from and upon. As such we can speak of an enacted dialogue with the past, exposed in the tension field created through the performers’ interaction with the documentary sources they have chosen at the outset of their performative investigations of the given space and time. Through the staging of their performative acts within the framework of the exhibition, they enable the viewer to bear witness to the invisible procedures performed by the artist, the institution, and art history, all aiming to maintain an idea of originality to be iterated infinitely in the future.