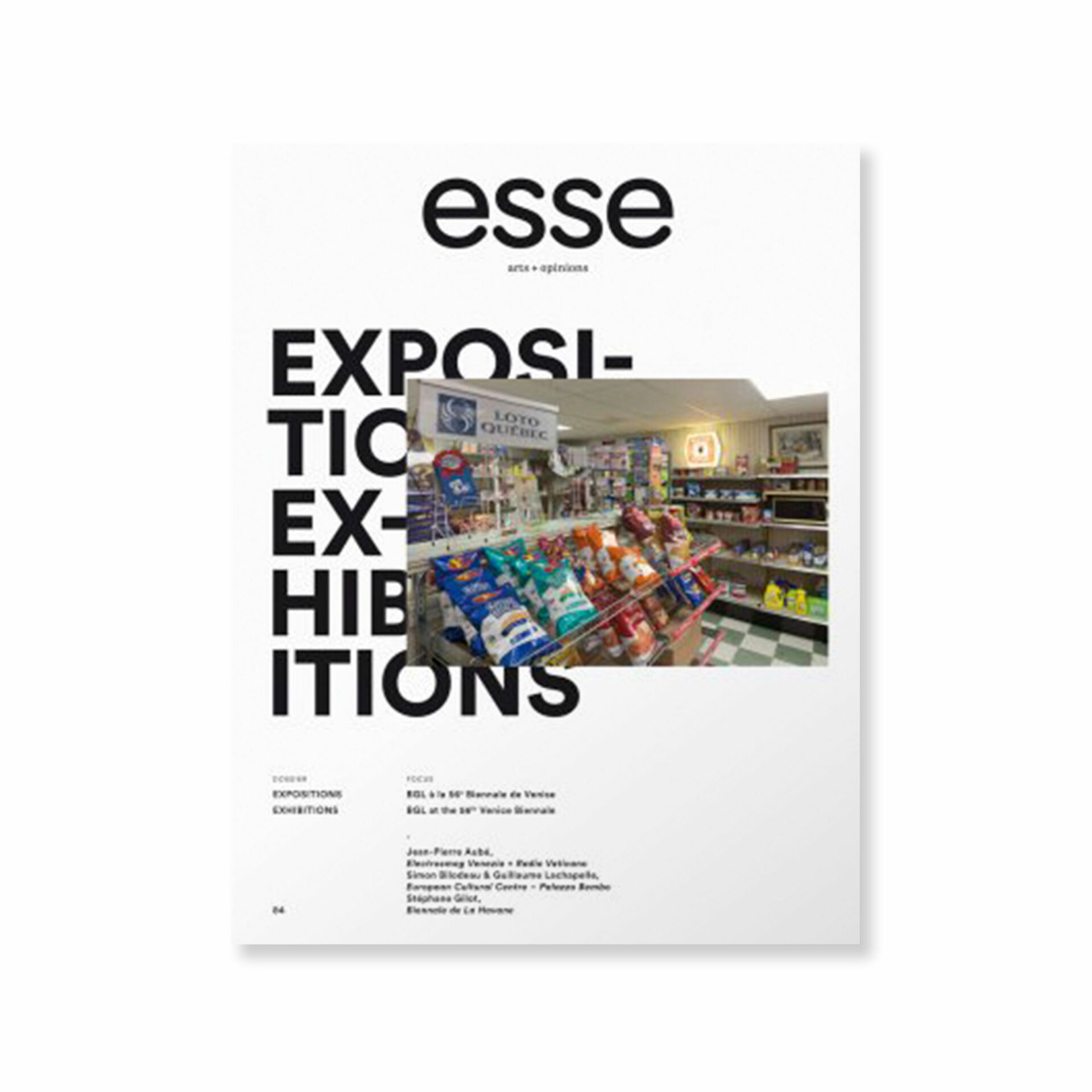

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

Selected to represent Canada at the 56th Venice Biennale (2015), the BGL collective — a designation formed of the initials of the three members’ last names (Jasmin Bilodeau, Sébastien Giguère and Nicolas Laverdière) — has been making provocative, disconcerting and materially demanding works since the mid 1990s. Their Italian project is based on a complete reconfiguration of the Canadian Pavilion, just as Gregor Schneider and Mike Nelson were able to do for the German Pavilion in 2001 and the British Pavilion in 2011 respectively, although taking totally different approaches. In an interview that intersects a closer reading (Marie Fraser) with a more general perspective (Thierry Davila) of their practice and their Venetian installation, Canadassimo, BGL offers some leads for better understanding this “playing field,” which they call the space in which art develops today.

Thierry Davila : You have chosen to work as a trio in a country where a significant number of artist collectives (Group of Seven, N.E. Thing Co., General Idea) have already made a lasting impression on history. In 2009, you in fact paid homage to the oldest one with Meatballs. Tribute to the Group of Seven. Have these predecessors influenced your work? How do you deal with this history?

BGL : No, not really. You know, our knowledge of art history is rather in its early stages. Besides the Group of Seven, we have also paid homage to Paul-Émile Borduas, who was the founder of the automatist movement in Québec and of the Refus global [Total Refusal], in Au service de l’impact (Hommage à Paul-Émile), 2012. These references to our pioneers are more like winks and nods than direct influences. They are somewhat like fish bait that we cast to titillate the experts.

TD : In concrete terms, how do the members of BGL work together? Is there a division of tasks? Does each member have an individual practice outside BGL?

Marie Fraser : The members of BGL have worked as a collective since they met at Laval University’s School of Visual Art in 1996, almost twenty years ago. None of them have pursued an individual practice. Having followed BGL’s work almost since the beginning and having been in regular contact with each member since they were chosen to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale, I realize that their working style is very organic. Nothing is predetermined, no one carries out a specific task, and, as there are three of them, they build their installations almost entirely themselves. Moreover, they often compare themselves to handymen or builders. Their work dynamic is very distinctive: the ideas circulate; they always remain in motion; they virtually never stop. The artists are almost always in the process of changing, removing or adding something. Even when a work is completed — that is to say, exhibited — reconfiguring the elements or transforming their relation to the space always remains possible.

TD : When we look at your work and try to understand it, we always begin by reading the titles, which, for the most part, are relatively long and literary. They seem more like the titles of films, novels or essays than the titles of artworks. Secondly, we have the feeling that discovering the work, exploring it and the surprises it has in store for us begins with the title. How do you devise and select the title of a work?

BGL : Our preferred medium is a direct experience of the work. Visitors inhabit the work without considering the existence of a title. Their understanding is empirical, physical. We provide titles because this has always been an important game for us. We are aware of the fact that only a few words can give a work greater breath, but we don’t always succeed. . . just like the works, for that matter! And, sometimes, the title must be displayed somewhere near the work: public movements and other ephemeral exterior interventions exist without a title in an anonymity that has its own value.

Meatballs. Tribute to the Groupe of Seven, 2009.

Photo : BGL, courtesy of Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

Arctic Power, 2008.

Photo : BGL, courtesy of Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

MF : The titles are often humorous and have a double meaning. For example, Meatballs. Tribute to the Group of Seven alludes to the fact that painting landscapes implies working in the woods. The allusion to the campfire and the idea of gathering around its warmth to share a meal draws our attention to the attitude of the Group of Seven artists and their way of painting much more than to the reputation of their works or their historical impact. It is a humorous, natural, and vital way of evoking the tradition of landscape painting, which is so present in Québec and Canada.

TD : You regularly create situations in which the spectators / visitors (who, it seems, are also authors of the work up to a certain point) are immersed. And they are often thrown off by what they encounter and experience (consider, for example, Domaine de l’angle 2 (2008), which completely blurs the boundaries between what is real — the real readymade — and the material invention itself), so much so that they no longer know where the work begins and ends. Are you fascinated not only by a powerful, physical relationship to space — a highly dynamic use of materials — but also by the fact of using the limits of discernment and perception as the subject of the work? Are experimentation and working with perception the dominant motifs of your research?

BGL : Yes, sensory perception: we relate to art through the senses. By making large installations that completely transform a space, we are able to place spectators directly inside the work, where they can walk around just as they do in their daily lives, at home or at work. We create a world which they enter and exit in record time, a kind of cinema of the real, a material, fictional state constructed out of familiar, though often altered, objects.

That’s the whole idea, as they say.

Each place becomes a new playing field to which we adapt, each space having its own resonance, history, culture, architecture (its physicality).

Let’s take for example Spectacle + Problème, an intervention installed at the Gymnase Ronsard for Nuit Blanche, in Paris in 2011, and subsequently presented at the Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne. These two experiences of the same work offered different perceptions and probably solicited different reflections relative to the place. The intervention context at the Gymnase Ronsard during Nuit Blanche, the fact that it was free, the work’s proximity to the street and the element of surprise undoubtedly suggested a delinquent act committed by pyromaniac loggers for some, while in a museum, this same intervention is inevitably interpreted as an artwork.

MF : It isn’t only the fact that perception varies from one place to another. You also seek to blur the perception one has of an object, a situation, or even art, so as to destabilize the spectator. If only through its title, Need to Believe evokes this kind of confusion. Artistique Feeling II, one of your most surprising works presented at the National Gallery of Canada in 2008, dropped Canadian banknotes from high up in the air. The banknotes spun around as though by magic, making museum visitors lose their bearings: surprised, on the one hand, to see money falling from the sky and, on the other hand, to realize that it was an artwork.

Jouet d’adulte, 2003.

Photo : BGL

Besoin de croire / Need to Believe, 2005.

Photo : BGL

Postérité-les-bains (Usine de sapins), 2009.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of BGL

L’orignal surnommé « Venise », 2004.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of BGL

TD : American philosopher R. W. Emerson writes: “Our life is not so much threatened as our perception.”1 1 - Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Experience,” Essays: Second Series, www.emersoncentral.com/experience.htm [Accessed on March 19, 2015]. Is this also your concern?

BGL : Good question. In the first place, we take up the perception of space. We are handymen-installers, Sunday afternoon mini-architects, builders seeking to understand the “velocity of places,” an expression that has been crucial to BGL from the beginning and which has also become the title of a public artwork to be installed in Montréal-North in summer 2015, as part of the art and architecture integration program.

In our eyes, our profession involves the exploration of great questions: What is beauty? What is reality, truth? In this world of infinite images, we deal with materials, their poetry. From our experiments in the studio, we keep our most promising discoveries. Then we share them with others, always in the hope of eliciting enthusiasm and the blah-blah-blah that forms the framework of our existence.

We’re basically trying to transcend materials and pervert objects: two excellent recipes for contemporary art!

TD : For the Venice Biennale, how did you tackle the Canadian Pavilion, its architecture and history?

BGL : When we visited it, it was completely empty; to us, it looked like a luxurious chalet from the 1960s, badly insulated, rarely occupied, but well located! Its window arrangement is remarkable and its “octagonal” (tipi-like) configuration is inviting and atypical.

It’s nice to get out of the large white cube from time to time.

We tackled it with joy, strength and courage. But doubt is never far-off.

MF : The Canadassimo installation completely transforms the Canadian Pavilion, while drawing inspiration from its architecture, scale, and geographical setting in the Giardini. As BGL emphasizes, its qualities are closer to those of a private and inhabitable space than of a neutral exhibition space. Furthermore, it is fascinating to observe that the aspect that usually puts artists off when exhibiting their works in this pavilion becomes the driving force of the installation for BGL.

The domestic scale is the starting point to some extent. BGL alludes to this by constructing an installation that leads visitors through three interior spaces: a dépanneur, the typical Québecois convenience store that stocks food and household products; a loft; and a studio packed with materials, all kinds of objects piled on top of one another and an array of tin cans dripping with paint and colour. The fact that the pavilion is relatively small compared to the neighbouring pavilions of Germany and England also prompted BGL to construct an exterior annex, a platform that serves as a resting area, like a terrace, and as a promontory from which to observe the Giardini.

There are many references to Québecois and Canadian nature and culture in the works of BGL: the forest comes up repeatedly; for a long time, wood was one of the favoured materials; the all-terrain vehicle flipped on its side in Jouet d’adulte (2003) alludes to hunting, but it is riddled with Native American arrows; the snowmobile in Arctic Power (2008) hangs like a frozen carcass or a “clean” artefact (Arctic Power is a brand of laundry detergent). In short, BGL’s handyman aesthetic also revives the traditions and know-how that are in danger of becoming obsolete. This all seems to culminate in the installation for the Venice Biennale, as evidenced by the intense emphasis that BGL places on Canada in the installation’s title.

Chicha Muffler, le dernier étage, 2014.

Photos : Ivan Binet, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

Rapides et dangereux, 2005.

Photo : Jean-Michel Ross, courtesy of BGL

Canadassimo, 2015 (details, work in progress)

Photos : Ivan Binet, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

TD : You have chosen to live in Québec City. Does this choice indicate a desire to distance yourselves from large urban centres in order to make work that is your own? Does the place in which you work and its context have a profound impact on what you do?

BGL : We like living here. There is no fierce competition with large centres. There are no large centres in the plural: there is only one 250 kilometres to the west and we like it immensely when we go there. Then, there are Toronto and New York. In Québec City, the small family of artists is close-knit, supportive, enthusiastic, and resourceful. Our rents and studios are affordable. It’s a romantic city where we could go to work on foot or by horse. There is a lack of parks in the city centre, but we remain hopeful. . . .

As we like to say, the budding ambassadors that we are, “Québec City is a rough diamond admired by Lévis in the river’s mirror.”

Translated from the French by Oana Avasilichioaei

Spectacle + Problème, 2011.

Photos : Marc Domage, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

Chapelle mobile, 1998.

Photo : Ivan Binet, courtesy of BGL

Domaine de l’angle II, 2008.

Photo : Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto