Of particular note among the events scheduled for the opening of this year’s Venice Biennale (May 6 – 8) are the live interventions of Québec artist Jean-Pierre Aubé. Under the guidance of Galerie de l’UQAM and its director, Louise Déry, this project aims at highlighting the singularity of an artistic practice that, by tackling hot-button issues such as electromagnetic pollution and cyber-surveillance, deserves both national and international recognition. In addition to the presentation at Venice, Déry has organized a more substantial exhibition of Aubé’s work to be shown at RAM radioartemobile, a flagship institution for sound art based in Rome that has recently showcased major artists such as Jannis Kounellis, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Jan Fabre. This exhibition, beginning May 14, brings together several of Aubé’s most ambitious projects from the past fifteen years, including V.L.F. Natural Radio (2000 – 04) and the magnificent landscapes in the Electrosmogs series (2009–), to which two new works — Electrosmog Venezia and Radio Vaticano, created with material collected in Italy — have been added. The following text draws on excerpts from a discussion in which the artist and curator shared their thoughts regarding the execution of this dual project.

Electrosmog Venezia, 2015, capture vidéo

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Electrosmog Venezia, 2015, capture vidéo.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Following her notable presentation of David Altmejd’s work at the Canadian Pavilion in 2007, Louise Déry received the support of the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec to elaborate what she calls “building-site exhibitions” for the Venice Biennale. The performance En exercice à Venise by Raphaëlle de Groot, presented at the 2013 edition, was the first of these experimental projects, whose initial objective was to increase the presence of Québec artists on the international scene.1 1 - For more on this project, see Sylvette Babin, “Raphaëlle de Groot. En exercice à Venise,” esse, no. 80 (Winter 2014): 82 – 85. Created without a specific infrastructure and with very restricted material and financial means, this “testing ground” allowed for the exploration of various possibilities for action as well as new strategies aimed at raising public awareness, in a hip, globalized artistic context which seems increasingly monopolized by the market and advances a glamorous conception of contemporary art. Going against this prevailing trend, Déry has in recent years sought to “re-centre [her] work on practices that are extremely focused and restrained, if not deliberately restricted: in terms of budget, duration — in all respects.” Indeed, it has become paramount for her to adopt a stance that considers not only the specific conditions under which an artist’s work may be shown at Venice, but also the aesthetic, logistic, ethical, ecological, and political implications inherent to this kind of project.

Choosing to launch a second “Operation Venice” with artist Jean-Pierre Aubé resonates perfectly with this logic. As Déry explains, “There are many artists with whom I could create a building-site exhibition, but only a few with whom I can see a direct link with the context of the Biennale. For it to work, this must be obvious.” In the same way that the 2013 performance by de Groot — who, in an elaborate disguise, glided along the city’s canals on a gondola — seemed evident, the pursuit, on Italian soil, of Aubé’s experiments using radio frequencies emanating from wireless communications systems seemed highly consequential on a conceptual level.

“When I did the project with Raphaëlle de Groot,” explains Déry, “I imagined the Venice Carnival procession. I saw the baroque splendour of the city, velvet capes, pageantry, wolves, masks, and wigs. For me as an art historian, it was therefore logical to envision such an intervention at this specific site. Two years later, at a time when we are urged more than ever to situate ourselves in relation to our communications, our methods of communication, and our relationships with the outside world, Aubé’s approach seemed extremely pertinent.”

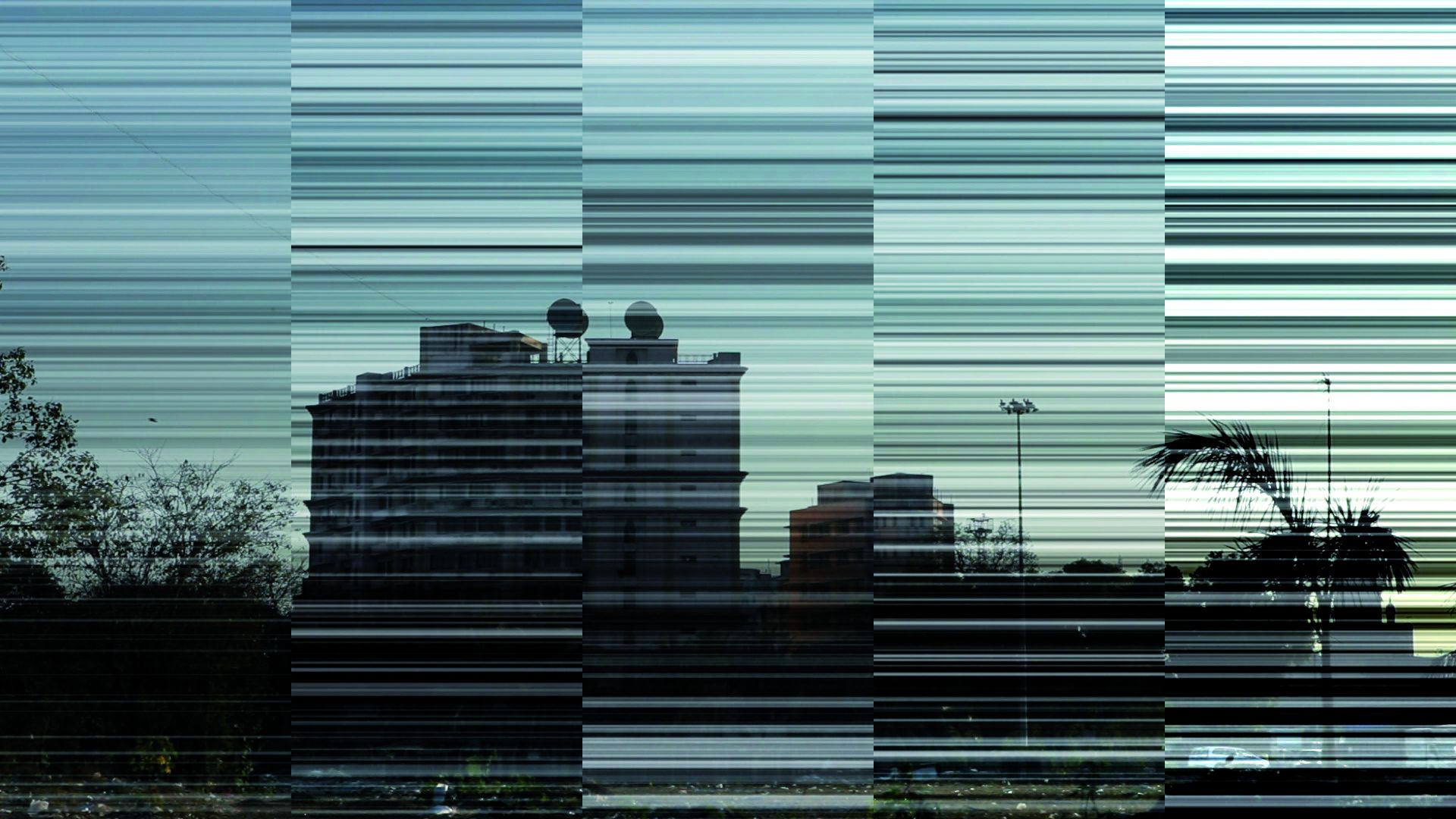

Electrosmog World Tour 2012, Mumbai & Istanbul, video stills

Photos : courtesy of the artist

Having previously investigated the waves emitted by natural phenomena such as solar winds, lightning, and the aurora borealis, Aubé has recently tackled technological disturbances caused by the various information, communication, and surveillance systems that “pollute” the urban environment with a staggering density of radio frequencies. By capturing, amplifying, and transposing this electromagnetic smog into audio and visual forms, the artist raises urgent questions about the excessive and often indiscriminate use of telecommunications today. Yet, as Déry observes, technology’s invasion of ecological and social space is a global phenomenon that the microcosm of the art world, coming together at major international events, obviously cannot escape: “At Venice, where we are all hyper-connected through our devices — making appointments here, sending reminders to go and see a certain artist there — it is worrying to think that we are exacerbating an already acute problem. Even though many in the art milieu maintain — or even flaunt — a certain degree of global consciousness, it is important not to forget the active role that we play in these invasive mass communication mechanisms. This is what Aubé’s work makes clear. Like a mirror, it shows us how banal we are, each with our iPad, photographing the same thing, lining up to see the same pavilion. . . .”

The problem raised by this normalized use of media devices has been the subject of numerous philosophical reflections in recent years. In his essay What Is an Apparatus?, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben contends that the technological formation of human behaviour brings into play a process of “desubjectification” that cannot be countered by simply deactivating or destroying our cell phones, for example, or, more naïvely still, by using them “in the right way.”2 2 - Giorgio Agamben, What Is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009), 15 – 17, 20 – 22. In our daily “hand-to-hand” struggle with such devices, according to Agamben, we must instead elaborate strategies that will restore to common use elements that, through technology, have been placed beyond our grasp or preserved in a separate sphere, like “sacred” objects.3 3 - Ibid., 17 – 19.

Echoing these philosophical considerations, Aubé has, over the years, developed an ingenious method that consists of seizing certain technological powers deemed, in his words, to be “from the realms of magic or science fiction, or sent from Allah or the planet Mars,” to then “modulate them in the language of art” in order to demystify their workings, at least in part. Through strategic use of his technical skills, Aubé thus endeavours to make visible or audible an imperceptible dimension of our reality, which must be captured, intensified, and felt for it to permanently pervade our consciousness. He also insists that his sophisticated technological manipulations are driven essentially by his aesthetic sensibility and an empirical approach to landscape inspired by documentary photography. In this respect, he says, “I’m not interested in developing a technique if I don’t have a deep aesthetic rapport with the subject. . . . As an artist, I am very aware that everything is processed with products by Apple — the largest company on the planet — right down to our fundamental relationship with art and culture.”

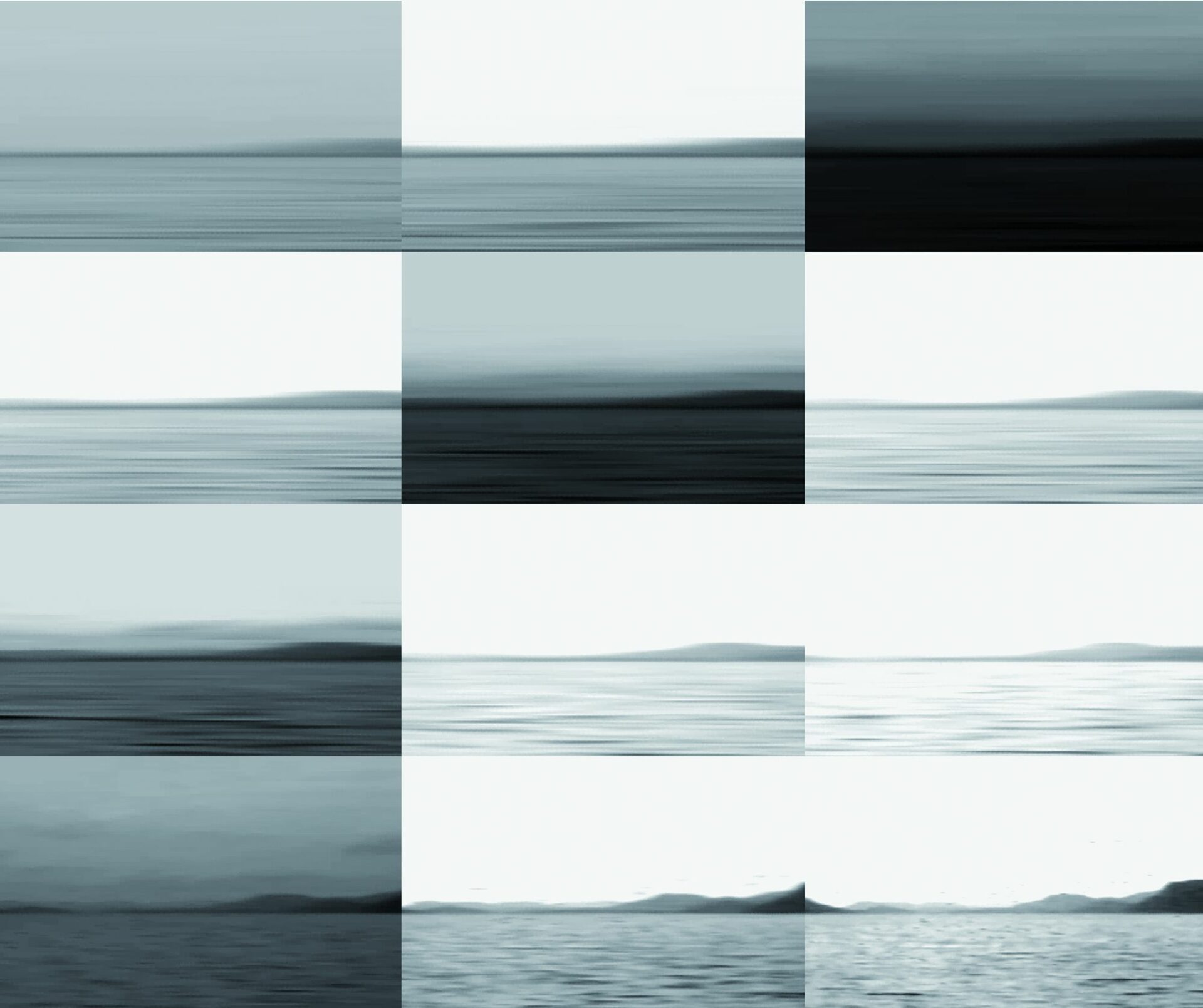

V.L.F. Natural Radio – Batiscan, Québec, 2001, video still

Photo : courtesy of the artist

V.L.F. Natural Radio – 21.12.2002 Jerisjärvi, Finland, 2002, video still.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

For the Venice project, Aubé chose to focus more specifically on the proliferation of cell phones, tablets, laptops, and other devices that shape contemporary life. His intention was to show how heavy this infrastructure floating above our heads really is (an infrastructure we imagine to be so light, transparent, and ethereal). Indeed, it is easy to forget that “every time we connect to our ‘gadgets,’ hundreds of machines are set in motion to process this information.” The little devices that we carry with us everywhere form an itinerant community ofwhat he calls “mini communicational beings.” “They constantly signal their presence and communicate their whereabouts to dozens of towers that criss-cross our cities. Among them, they share, encode, and decode millions of little information packets.” Insofar as all of these messages are generated by humans, the crowd gathered during the professional days of the Biennale presented an ideal context for collecting and decoding information, and eventually retransmitting it in another form.

Having pinpointed locations during an initial visit with Déry, who knows the city well, Aubé imagined what he describes as a “theatre” in two parts: during the day, he would wander the city with a small group of “pirate” assistants, tracking visitors’ personal devices and gathering data via antennae, receivers, and computers placed on a gondola; in the evening, he would proceed with live experiments at campo Santa Margherita, a typical Venetian square where a discerning public of art professionals, capable of detecting the covert presence of artistic gestures, usually gather for the opening of the Biennale. The exact nature of these experiments had to be carefully considered, as neither sound nor musical interpretations of radio frequencies, such as those in the Electrosmogs series, easily lend themselves to outdoor performance. Hence the idea of a display of light signals that would surreptitiously light up in the darkness of the night — like tiny “fireflies,” as Aubé explained. The subtle radiance of these nocturnal insects, already invested with numerous poetic and political meanings,4 4 - See, among others, Georges Didi-Huberman, Survivance des lucioles (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit : Paradoxe, 2009). and whose existence is threatened by air and light pollution, functions here as a visual metaphor for ambient electromagnetic activity. In the more concrete form of light “graffiti” projected on the buildings of the campo, at the heart of which stands a police facility bristling with antennae and surveillance cameras, selected pieces of information concerning this communicational infrastructure will reveal themselves to those with a watchful eye. Thus, like the intermittent “beeps” that punctuate our conversation in the artist’s studio, signalling the passing of a spy satellite overhead, these luminous messages signal the presence of a “system of permanent registration,” to use a term of Michel Foucault,5 5 - Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Random House, 1995), 196. whose analysis of the theatre of surveillance in question here is still of great relevance today.

Radio Vaticano, 2015, video still.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

As Foucault underlines in Discipline and Punish, the machinery that assures the surveillance of contemporary society is governed by an automatic, disindividualized, visible, and — most importantly — unverifiable power. Consequently, and contrary to the idea that control is exerted by inaccessible forces, any individual can operate this machine, whether the motivation is protection, security, maintaining order, or the thirst for knowledge; or perverse curiosity, pleasure in spying, terrorizing, and punishing.6 6 - Ibid., 201 – 02. In an era when the infiltration of IT systems and the invasion of privacy represent tangible threats, resorting to piracy for artistic purposes, as Aubé does, raises both ethical and technical questions as to the limits of art. Put simply, artists must ask themselves how far they are willing to go ethically, and how far they are able to go technically, in face of this dilemma.

For Déry, what counts above all else is “how an artist sifts through the constant deluge of information and events; in other words, how he chooses the issues that become the raw material for his artistic research. Because,” as she insists, “Aubé is not a hacker. He’s an artist.” An artist whose practice calls for a responsible approach by the curator — resulting, in this case, in a project without a footprint: “We take nothing, we leave nothing, we just pass by.” Together, Déry and Aubé have created a context in which certain experiments can be performed, without predicting the results or consequences, but with the firm conviction that they are making a sensitive and meaningful contribution to the world.

Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft