Indigenous Intemporalities and Performative Futurities

Attempting to undo this knot are proponents of Afrofuturism, a multidisciplinary movement that crystallized at the turn of the 1990s in response to theoretical, political, and ultimately aesthetic lethargy. A hybrid object articulated around the notions of Africanness, civil rights, science fiction, and futurity, Afrofuturism is positioned as a philosophy of emancipation and free will, using an array of practices and knowledge precluded from modern Western thought. Although the term first gained critical traction following the publication in 1993 of Mark Dery’s article “Black to the Future,” in response to his students’ art production combining postcolonialism and new science and technology, such creative métissage emerged long before this postcolonial flood. Reynaldo Anderson, theoretician and cofounder of the Black Speculative Arts Movement, attributes the rise of “Black speculative thought”1 1 - « Black speculative thought » [trad. libre]. Anderson favours this umbrella term over “Afrofuturism.” Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones (eds.), Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness (Minneapolis: Lexington Books, 2015). to the influence of Afro-American literature at the turn of the nineteenth century, including the works of novelist Pauline Hopkins and writer W.E.B. Du Bois. Their writings, resembling antiracist socio-political analyses, with subjects such as the foreigner, the machine, space, and a utopian future, take a critical and constructive look at the notions of difference, progress, territory, and agency. Picking up on their ideas, Afrofuturism envisages liberating decolonial alternatives to a future that can no longer be considered a simple and inevitable consequence of the past.

This tension between tradition and contemporaneity sets the course for another movement parallel to Afrofuturism, one that is also anchored in a theoretical and aesthetic conception of an emancipatory future: Indigenous futurism. Defined by Anishinabe theoretician Grace Dillon in Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fictionthe expression finds its roots in images, themes, and methodologies that draw on science fiction with the aim of modelling a future from an Indigenous perspective as “a way to renew, recover, and extend First Nations peoples’ voices and traditions.”2 2 - Grace L. Dillon (dir.), Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 2012): 1-2. Less central in the Afrofuturist narrative, questions of tradition, memory, and transmission are at the heart of the Indigenous futurist imaginary. This valorization of the symbolic and material heritage of past generations in the constitution of Indigenous identities becomes fertile ground, here, for reflection on possible futurities beyond the assimilationist tropes of colonialism.

Inspired by Molly Swain, one of the hosts of the podcast Métis in Space, and her vision of a dystopian now, Lindsay Nixon, Two-spirit curator of Cree-Métis-Saulteaux origin, adopts a stance that counteracts the putative spatiotemporal sequence mapped out by modern Western society. Suggesting a specifically Indigenous epistemological prerogative regarding the future, Nixon underlines, “We are the descendants of a future imaginary that has already passed; the outcomes of the intentions, resistance, and survivance of our ancestors.”3 3 - Lindsay Nixon, “Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurisms,” GUTS, May 20, 2016, <http://gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures/>. The notion of survivance — a neologism at the intersection of survival and resistance — also central to Dillon’s thought, illustrates the resilience of First Peoples and affirms a timeless identity. For many Indigenous artists, this intrinsic and historical resistance to being inscribed in a temporal linearity (with the advent of colonialism marking an important hiatus in this sequence) opens the door to an imaginary in which time is tractable, simultaneous, or simply not referenced. Furthermore, the utopian projection into an “Indigenized” and performative future responds to the communities’ vital need to architect renewable tomorrows.

Confronted for centuries by myriad forms of violence (cultural, environmental, territorial, familial, and others), many of these communities are attempting to advance a positive and empowering vision of their identity that takes into account a complex cultural legacy in which traditions, contemporaneity, and aspirations overlap.

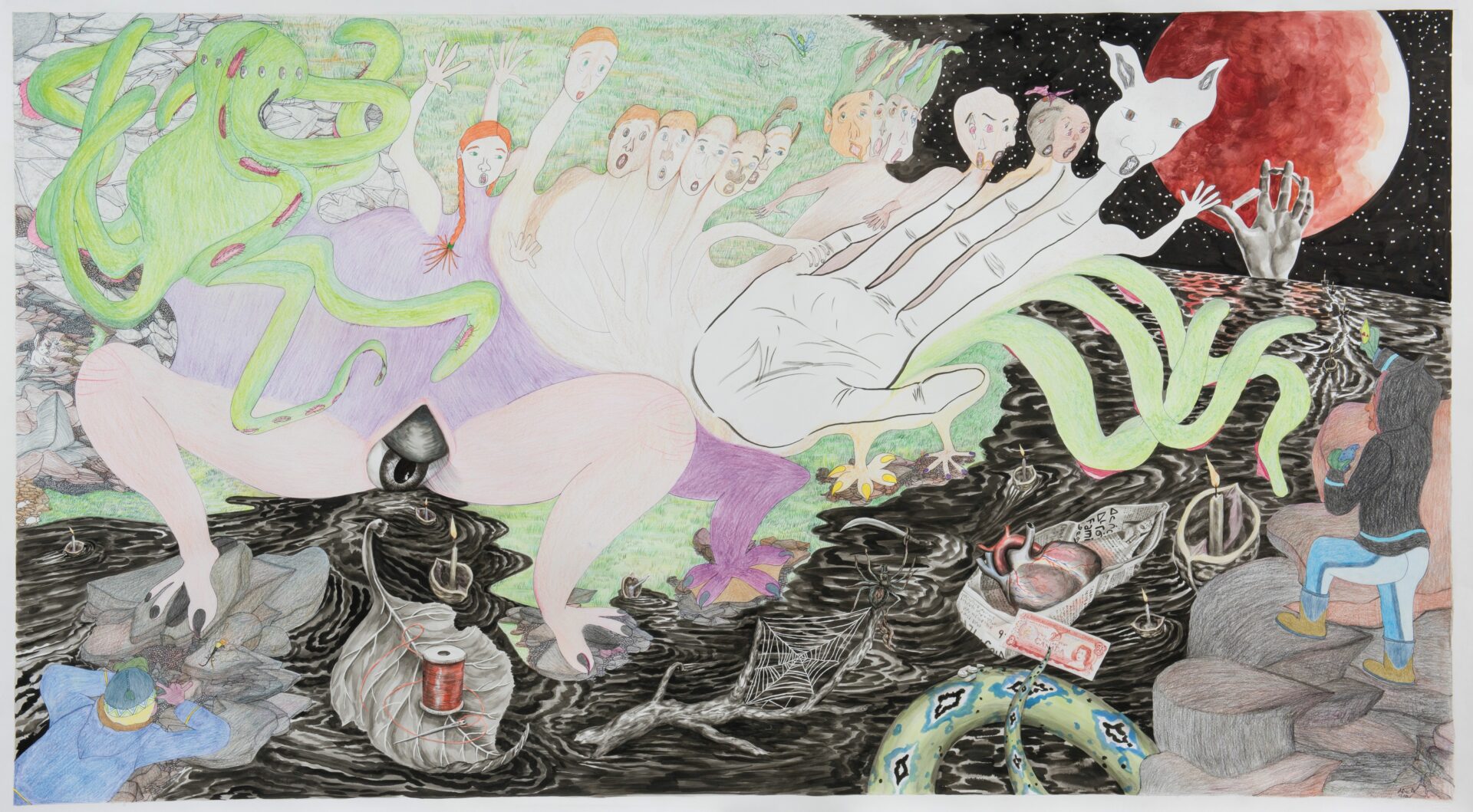

This notion forms an important anchor in the work of Inuit artist Shuvinai Ashoona, who draws inspiration not only from the universe of comic strips and horror films but also from Inuit traditions and legends. The encounter between these worlds is central to her work: the North is united with the South, the imaginary with the real, and the past with the present in a spirit of future-oriented collaboration. This symbiosis of knowledge and cultures, transmitted from generation to generation, conveyed by the Inuk word Qaujimajatuqangit, is a motif in many of Ashoona’s drawings, including Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands)(2007–08) and Inagododavida (2015), works created in collaboration with Toronto-based artist Shary Boyle during the latter’s residency in Ashoona’s native village, Kinngait. Ashoona’s fantastical and traditional iconography debunks stereotypical representations associated with Inuit art by adding to the classic images of Arctic landscapes, fishermen, fish, and seals,images of extraterrestrial creatures, mythical goddesses, and dragons. In Composition, characters from Inuit mythology, the animal realm, and Ashoona’s community gather in a circle, forming a kind of Council of the Wise to contemplate the future of the animal world. Earth itself is portrayed alongside siren goddess Sedna and an Inuit woman nursing her children in the embrace of an ancestor, suggesting a holistic intergenerational and interspeciesist vision of the artist’s future. Inagododavida transports us to what Ashoona calls an intergalactic universe inhabited by surrealist beings (a “Northern” universe, nevertheless, given the typical Inuit clothing worn by those portrayed). This strange yet familiar extraterrestrial world seems to poke fun at the curious exoticism sparked by colonial exploration. Free and humorous associations among oneirism, history, mythical creatures, spatial explorations, and Inuit objects and figures form the narrative thread of Ashoona’s compositions, expressing a hybrid vision of the future beyond racist and dualist schema: “Imagining racialized becoming in place of racializedothering.”4 4 - Dillon, Walking the Clouds, 65.

Inagododavida, 2015.

Photo : courtesy of the artist & Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto & Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, Montréal

This critical yet benevolent approach is emblematic of a generation of Indigenous artists avid for change but also disappointed by unfulfilled promises of reconciliation. Truncating the tacit violence of broken governmental promises regarding reparative justice for wrongs committed against Indigenous peoples, Ashoona solicits an empathic, less-moralizing vision of living together by depicting improbable meetings between different forms of life and the non-living. The notion of otherness is embodied here by both our conception of humanity and our perception of knowledge, technology, and other spheres. Far from affirming that there is no trace of socio-political critique in Ashoona’s practice (quite the contrary), the visual strategies that she uses avoid the pitfalls of misguided appropriation and accusatory confrontation, making way for the creation of spaces rich in harmonious potential. As author and activist bell hooks suggests, the creation of harmonious spaces,a term that she favours oversafe spaces, is not synonymous with consensus but instead denotes the risk, chaos, and discomfort inherent to the recognition of difference and to the joint commitment of individuals to safeguarding common welfare, despite divergent opinions and identities.5 5 - The New School, “bell hooks and Laverne Cox in a Public Dialogue at The New School,” 1:36:8, October 13, 2014, <www.youtube.com/ watch?v=9oMmZIJijgY>.

Composition (People, Animals, and the World Holding Hands), 2007-2008.

Photo : courtesy of Dorset Fine Arts, Toronto

The desire to create a performative space to generate alternative futures — or, at least, the desire to establish a “virgin” territory free of the millstone of history — is also an important leitmotif of Indigenous futurism. In her book Reconciling in the Apocalypse, Nēhiyaw philosopher and militant Erica Violet Lee emphasizes the necessary reciprocity between the idea of a lasting reconciliation and that of a space conducive to the development of Indigenous identities. Although Lee envisages nature as the favoured bedrock for crystallizing this reconciliation, the virtual universe also offers a solid foundation for the construction of Indigenous futures. Mohawk artist Skawennati’s multimedia practice is indispensable for those interested in reflecting on this question of future Indigenousness through the appropriation of technologies. Co-founder of the research-creation collective Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC), a network dedicated to the presence and visibility of Indigenous communities on the web, Skawennati utilizes the virtual world as a platform for empowerment, with cyberspace being the terra nullius of tomorrow’s Indigenous identities..

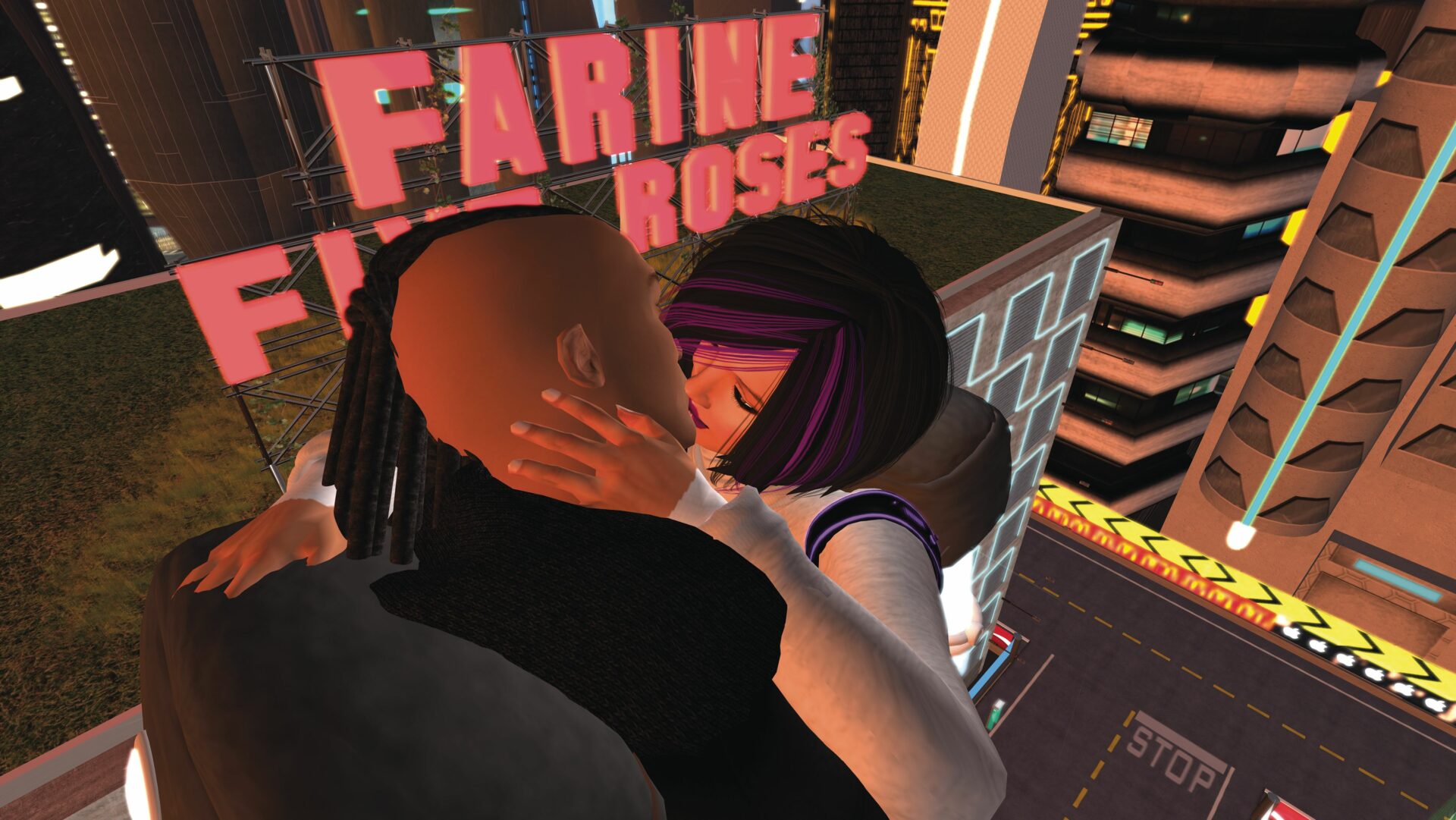

By building on a participative aesthetic and narrative common to personification games, Skawennati’s work TimeTravellerTM (2008–13) tells the story of Hunter, a young Mohawk from the twenty-second century, and Karahkwenhawi, a twenty-first-century Mohawk, who travel to the past to connect with their people’s history. Comprising a series of nine machinimas (short films created in the virtual environment of the game Second Life), the project relates major historical events such as the Oka Crisis and the death of Mohawk saint Kateri Tekakwitha. Active witnesses performing their past (Hunter and Karahkwenhawi embody certain emblematic figures in these events), they no longer act as passive extras in history but reappropriate the narrative weft of their heritage, as well as agency over their future. With these historical back-and-forths, Skawennati invites us to reconsider the colonial narrative of North American modernity through the gaze of the colonized. A central motif in this series is eyeglasses (the TimeTravellerTM), a precious gadget with which the protagonists travel. This aestheticism, which could be linked to magical realism or the re-enchantment of the ordinary, proposes a reappropriation of history and the real, while taking into account an Indigenous cultural métissage specific to decolonial thought; this new métissage calls for a re-spiritualization of the Western imaginary and consciousness.

Becoming the Peacemaker (Tekanawí:ta) machinimagraphs from the project, 2017.

Photo : with support of AbTeC, courtesy of the artist & Ellephant, Montréal.

Again here, time overlaps in a non-linear fashion, thus challenging the web’s potential to offer a habitat for a truly decolonized space-time.

In a nod to the Star Warsfilms, the machinima The Peacemaker Returns(2017) also plays out in a disjointed temporality. Set in 3025 on a planet Earth in the midst of an invasion, this futuristic saga presents the story of Iotetshèn:’en, a spaceship-confined Iroquois whose mission is to create an intergalactic alliance for peace and the transmission of Indigenous knowledge. Initially created for a young audience (five- to eleven-year-olds), the work familiarizes viewers with First Nations traditions and practices, thus allowing history to be experienced from an Indigenous perspective. Set in front of what seems to be a futuristic longhouse, the video depicts numerous avatars, both historical (Jacques Cartier, Donald Trump, Kateri Tekakwitha) and fictional (Iroquois with supernatural powers and all kinds of extraterrestrials), in a way that conveys a positive and updated view of Indigenousness as a legitimate culture of the future. In line with the artists of cyberpunk, a sub-genre of science fiction in which antiheroes exist in post-apocalyptic techno-deficient universes, Skawennati proposes a No Future view of colonial times, as put forward by the progressive ideology of the Enlightenment, while debunking an oft-proposed and outdated view of Indigenous identities.

This version of colonial times is cadenced by technological advancements that, as Two- spirit Navajo author Lou Cornum underlines, are falsely claimed to go hand in hand with social and humanist revolutions—an ideology that Indigenous futurism also questions: “Indigenous futurism seeks to challenge notions of what constitutes advanced technology and consequently advanced civilizations… Extractive and exploitative endeavors are just one mark of the settler death drive, which indigenous futurism seeks to overcome by imagining different ways of relating to notions of progress and civilization.”6 6 - Lou Cornum, “The Space NDN’s Star Map”, The New Inquiry, January 26, 2015, <https://thenewinquiry.com/the-space-ndns- star-map/>.

Watching the News Behind the Barricades, 2010, machinimagraphs from the project 2008-2013.

Photos : with support of AbTeC, courtesy of the artist & Ellephant, Montréal.

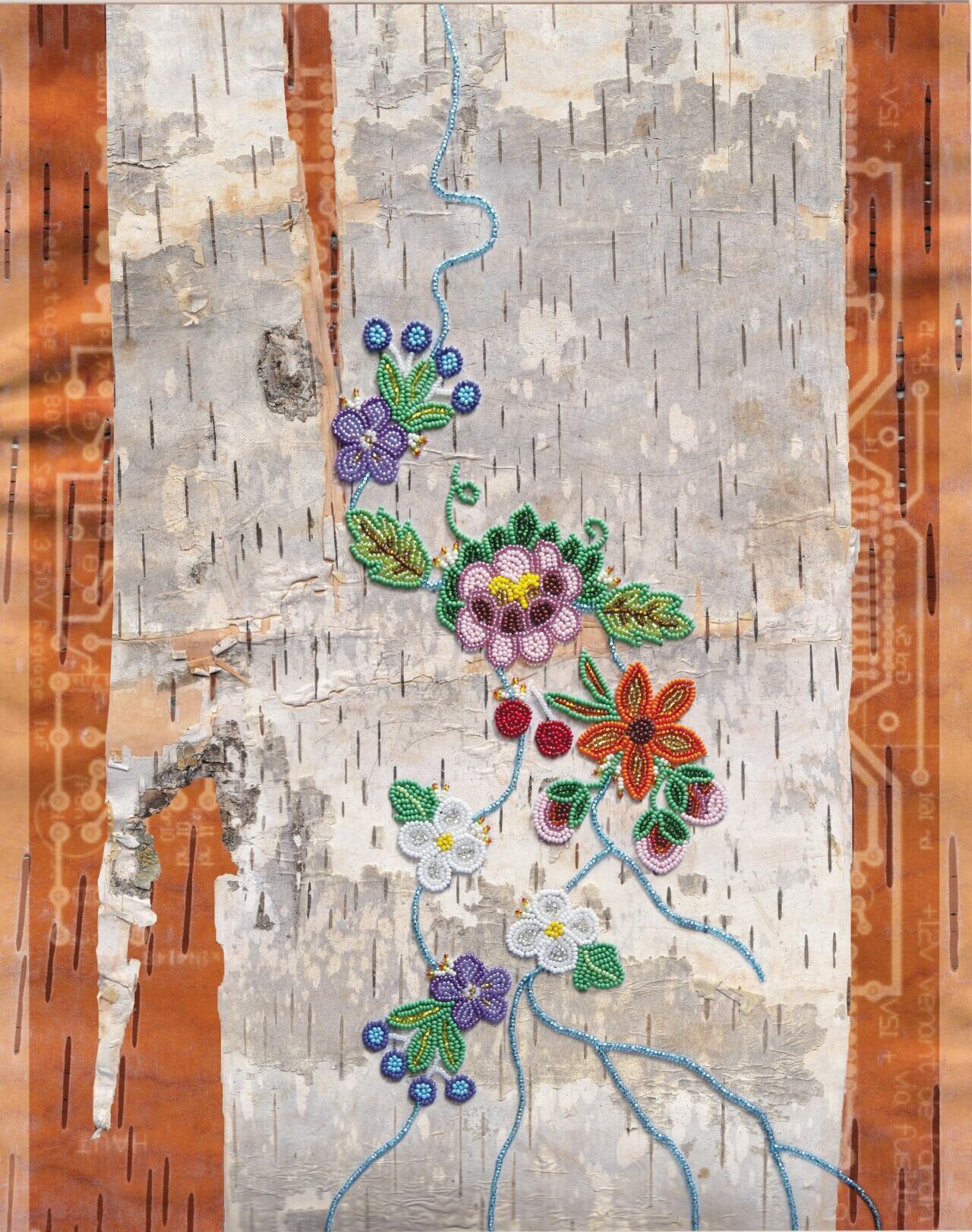

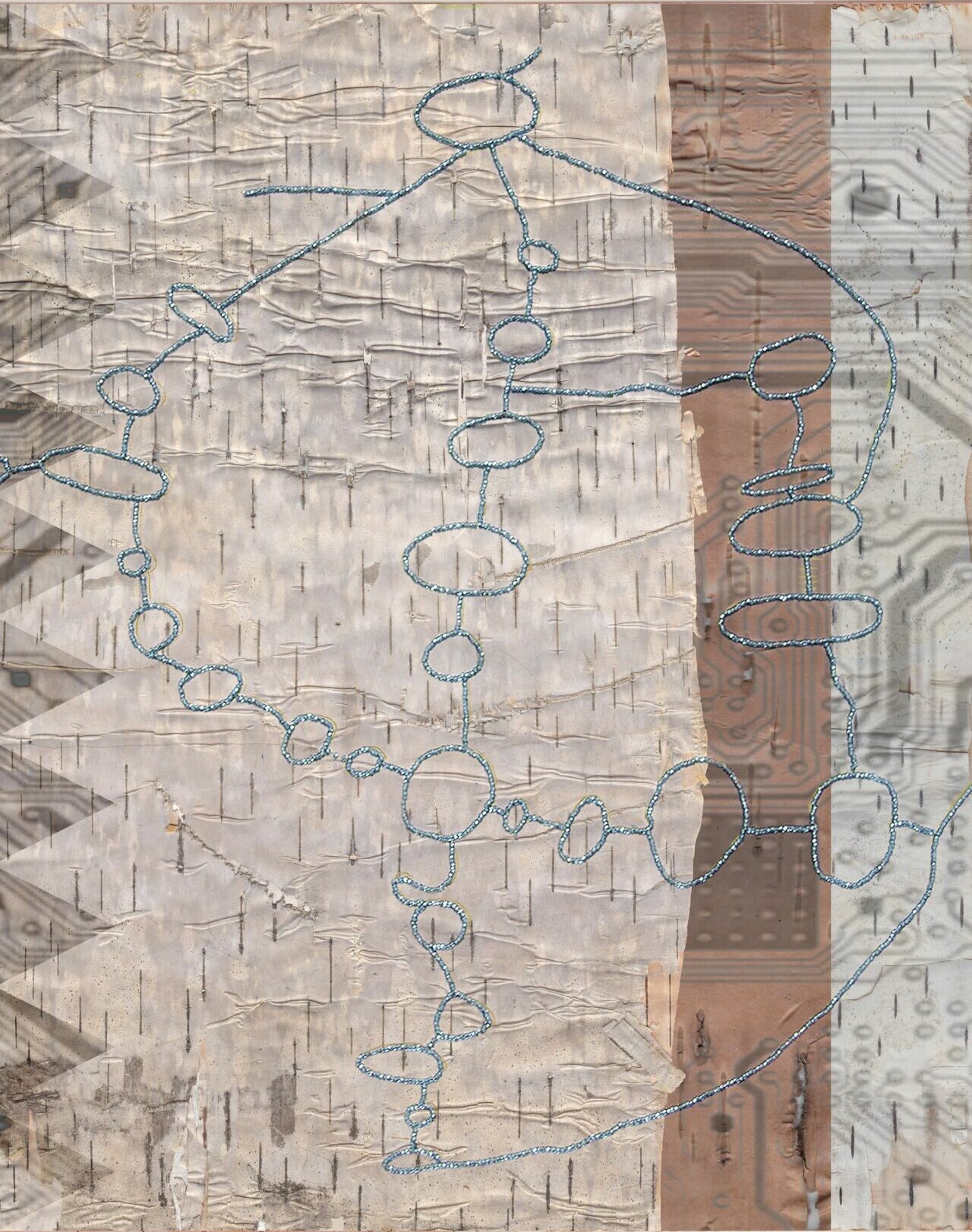

These endeavours are imported by colonialism and undermined by a futurity portrayed or imagined by Indigenous artists. Apocalyptic scenes of infinite cities inhabited by encapsulated beings suffocating from pollution are exchanged for blended entities or objects — in symbiosis with an animistic form of nature—that draw on ancient technology and wisdom. Traditions and customs are no longer the purview of the past but the heritage of the future, radically overturning relationships with time, heritage, and the imaginary. Sensitive to these reciprocal relationships between nature and technology, Cree-Ojibway artist KC Adams deconstructs technophobic stereotypes that stigmatize Indigenous peoples and circumscribe them to the past and a kind of primitivism. Combining painting, beading, and digital prints of circuit boards, the Birch Bark Technology series (2017–20) reflects the very concept of “technology” through the motif of the river. Printed on birch bark are images of circuit boards onto which blue glass beads have been sewn to create abstract maps evoking hydrographic networks (Gage’gajiiwaan, 2020) and topographic perspectives (Close to the Water, 2020). In Adams’s work, overriding the simple metaphor of a vital artery that ensures the free circulation of human, cultural, or material capital, the river takes on the form of a timeless technology that requires an inherent understanding of the territory and the mastery of precise knowledge regarding nature, the climate, riverside communities, and other elements —knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation and that Adams wishes to bring to light. Following in the vein of the technical expertise associated with the construction of Machu Picchu or the pyramids and the scientific interest that they elicit, Birch Bark Technology suggests a technologically “advanced” Indigenous past, in stark contrast to the reactionary vision set forth in the grand narratives of modernity. Without claiming to be “superior” to contemporary epistemology, ancestral wisdom rooted in nature invites us to rethink our conception of progress and to dismantle the false dichotomy that sets culture against nature, and future against Indigenousness.

Water is Life, from the series Birch Bark Technology, 2020.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Gage’gajiiwaan, from the series Birch Bark Technology, 2020.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

The reappropriation of the future by Indigenous imaginaries is an essential part of this long process of decolonizing savoir-faire. The evocative power of science fiction and its capacity to mobilize identity-related futures emancipated from history — a history built on the pillars of colonialism, patriarchy, and capitalism— thus paves the way for yet unimagined futurities. In this sense, Indigenous futurism, fundamentally political and performative, shares the preoccupations of feminist, anarchist, and ecological movements in advocating for a radical overhaul of how we live in the present and imagine our future.

Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft