Photos : Geneviève Massé © DARE-DARE, permission de L'artiste | courtesy of the artist

In June 2012, at the height of the Maple Spring demonstrations, ten or so individuals wearing identical t-shirts sat down on the edge of the sidewalk in front of Brasserie T! at Place des festivals to eat sandwiches. When they were asked by technicians from Équipe Spectra1 1 - Équipe Spectra is one of the major players in terms of cultural production in Montréal, as it is responsible for three festivals (Jazz, FrancoFolies, and Montréal en lumière) and the owner of the concert venues Métropolis, L’Astral, and House of Jazz. Its vice-president, André Ménard, sits on the board of directors of Quartier des spectacles. to explain their presence, one of them handed over a card on which was written: “Using public space is a privilege and not a right.”2 2 - The sentence is taken from the Partenariat du Quartier des spectacles website (our translation). A series of tense telephone calls between Équipe Spectra and the administration of Quartier des spectacles ensued, finally reaching DARE-DARE, which was coordinating the performance: the administration ordered it to immediately stop these “political” acts. With Anne-Marie Ouellet’s Secondes zones project,3 3 - Anne-Marie Ouellet, Secondes zones, an intervention project hosted by DARE-DARE from May 18 to June 27, 2012. Project website: http://secondeszones.blogspot.ca/ the relationship between DARE-DARE and its new host, Quartier des spectacles, began in an atmosphere fraught with suspicion.

Even though these relations have since returned to normal, they nevertheless shed light on the growing tensions among stakeholders, for whom culture represents an economic mainspring, and artists, for whom profit is not the primary objective — and, between the two, the organizations that are trying to preserve their assets amidst the storm clouds brewing over cultural policy.

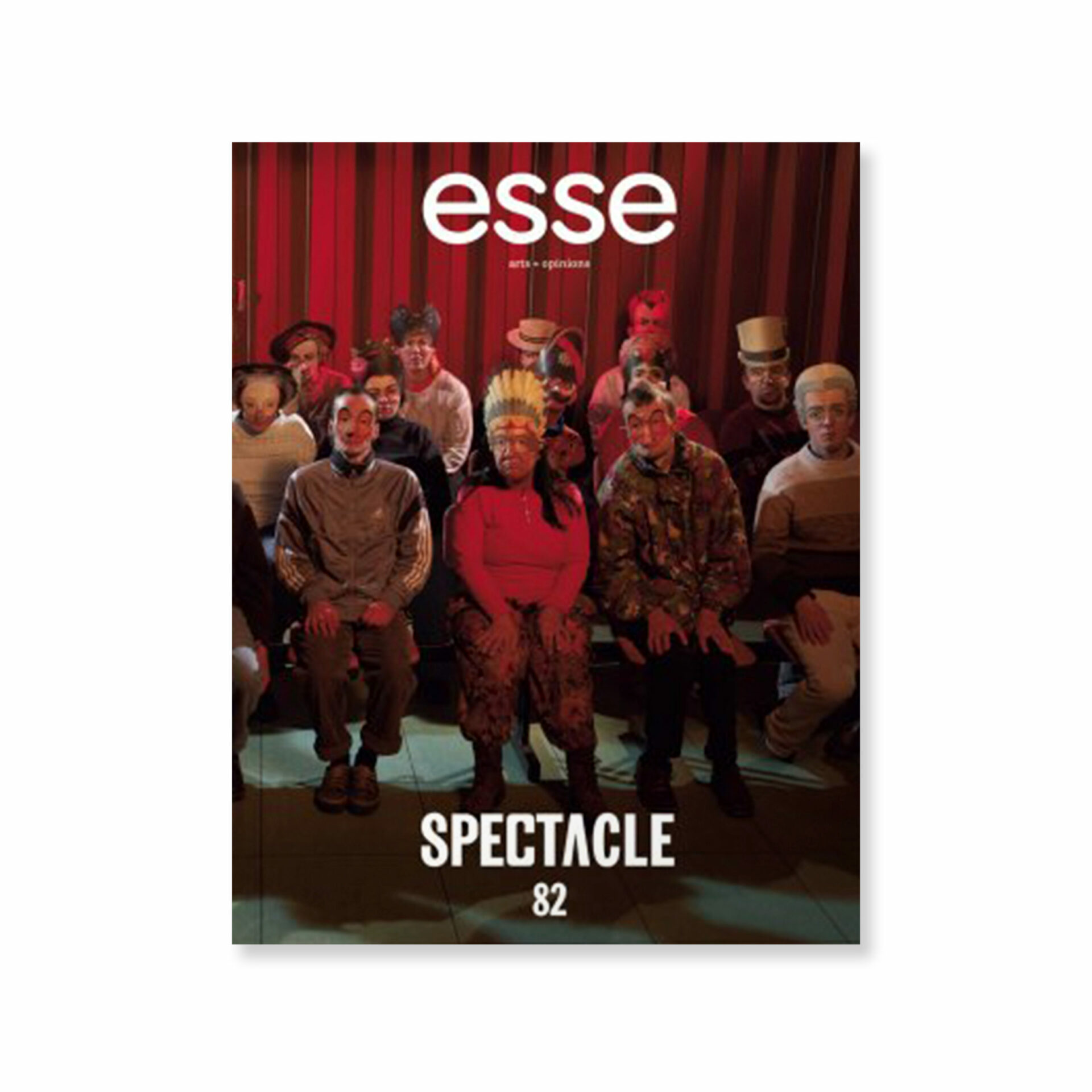

ma intervalles (actions infiltrantes), parterre, vitrine événementielle, Quartier des spectacles ;

banc rouge, Place des arts, Montréal, 2013.

Photos : Geneviève Massé © DARE-DARE, permission de L’artiste | courtesy of the artist

DARE-DARE In An Urban Power Zone

Since 2004, artist-run centre DARE-DARE has been nomadic, a fact that inspired its growing — and now exclusive — interest in art practices in public spaces. Based in a mobile trailer, the organization moves from one neighbourhood to another, following offers from the Ville de Montréal and the wishes of its members. Since March 2012, the DARE-DARE trailer has been located on the vacant lot surrounding the Saint-Laurent metro station, under the auspices of the Partenariat du Quartier des spectacles, which manages the space.

The choice of Quartier des spectacles, a large district devoted to a culture of spectacular light and sound performances, may seem surprising for a centre usually interested in less ostentatious practices. And yet, for DARE-DARE, it was precisely a question of defying expectations. As Martin Dufrasne, coordinator of the centre since 2010, explained, the members wanted to get away from marginal spaces — the usual playground for artists — to draw closer to the centres of power.4 4 - Interview with Martin Dufrasne, March 21, 2014, Montréal (our translation). Conversely, the Partenariat du Quartier des spectacles, at the time, seemed interested in preserving less conventional creative forces in its environs — an interest that, in retrospect, seems to have been based on ignorance. “On their part, there was an understanding that we would perhaps organize activities,”5 5 - Interview with Geneviève Massé, March 23, 2014, Montréal (our translation. notes Geneviève Massé, co-coordinator, with Dufrasne, of DARE-DARE. The few meetings held prior to the arrival of the centre in its new location were not enough to dispel any mutual misconceptions: it took the reality of an initial project to test the limits of this nascent cohabitation.

Secondes zones

With Secondes zones, Ouellet wished to deepen her exploration of public space and how it is used — a theme central to her practice. The relocation of DARE-DARE, which was assisting her with her project, to Quartier des spectacles sparked her interest in the specific characteristics of this still-new site. Consequently, she put together a group of volunteers who were responsible for choosing and performing a series of actions in and around Place des festivals.6 6 - Place des festivals is part of Quartier des spectacles, situated west of the Musée d’art contemporain, between Président-Kennedy, Sainte-Catherine, Jeanne-Mance, and Bleury Streets. For the occasion, all of them wore t-shirts bearing an ambiguous symbol that discreetly identified them. The actions that they performed played on the ambiguity between the banality of their gestures (standing up, sitting down, approaching a group, facing or turning away from a stage) and the spectacular — or worrying — effect that these gestures might have when performed by a group. In Ouellet’s view, it was a question of “seeing how these actions were perceived by the public in a space already devoted to entertainment.”7 7 - Interview with Anne-Marie Ouellet, March 16, 2014, Montréal (our translation). It was also a matter of testing the limits of what is authorized in this space where everything seems primed for controlling use.

The first day of actions went smoothly in the calm atmosphere of an uncrowded Place des festivals. The ten participants in the project moved around as planned, all together and in subgroups, coming together on the stairs in choir formation before returning to the DARE-DARE trailer. Meanwhile, on this seemingly insignificant day, May 18, the National Assembly of Québec was in the process of adopting the controversial Bill 78 (which, ironically, in its original draft, restricted gatherings of ten or more people). The political context, which placed Quartier des spectacles at the centre of relentless demonstrations, undoubtedly made the administration more apprehensive about unidentified activities, especially those involving groups.

Secondes zones, Place des festivals, Quartier des spectacles, Montréal, 2012.

Photos : Geneviève Massé © DARE-DARE, permission de L’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The second action took place two weeks later. The participants chose to reproduce the lunchtime routine of workers who use this outdoor space, but without respecting the zones set aside for this purpose. Having sat down on the edge of the sidewalk in front of Brasserie T! to eat sandwiches, they were reminded by a waiter that “there are places for that.” Obediently, the group got up to sit down farther along the closed-off street. Later, before the group separated, each member lay down between the lines of switched-off fountains. Even though these actions were no more or less threatening than those undertaken in the first intervention, they were performed while the stages were being set up for the launch of the FrancoFolies festival, which occupies Place des Festivals for several weeks and is organized by Équipe Spectra. The team’s technicians made calls, more alarmed than reassured by the cards bearing the message “Using public space is a privilege and not a right” that were offered to them by the performers. On their return to the trailer, Ouellet and Massé, who were coordinating the project, discovered anxious messages on the centre’s voicemail. In one of them, the programmer for Quartier des spectacles ordered DARE-DARE to inform it in advance of any activity to be performed and to immediately stop distributing cards. The centre agreed.

Design and Lighting

Quartier des spectacles encompasses three of Montréal’s urban “hubs”: Place des arts, Quartier Latin, and the intersection of Saint-Laurent and Sainte-Catherine Streets. Since 2009, it has been administered by the Partenariat du Quartier des spectacles, an autonomous body created by the city under the leadership of the ADISQ and the city’s major festivals. Apart from promoting the Quartier as a tourist destination, the Partenariat’s mandate is to see to the “animation of the area, the management of public spaces, and the enrichment of general cultural offerings.”8 8 - Le Partenariat du Quartier des spectacles, 2014, http://www.quartierdesspectacles.com/fr/a-propos/partenariat-du-qds (our translation). Serving on its board of directors are mainly large-scale cultural organizations and businesses, with only one representative for the neighbourhood’s residents and no representation for the local community.9 9 - Ibid. Reflecting only the most visible and lucrative extremes of the cultural spectrum, the Partenariat promotes an extremely specific vision of culture, reduced to the role of economic lever and tool for urban renewal.10 10 - For more on this subject, see Laurence Liégeois, “Espace labyrinthique et contrainte: Quelles stratégies d’aménagement pour les espaces publics? ” Géographie et cultures 70 (2009), http://gc.revues.org/2290 (accessed June 24, 2014).

In this perspective, the type of culture promoted in Quartier des spectacles welcomes diversity, spontaneity, and incongruity only if it does not interfere with the area’s principal objectives of social harmonization and branding. Although the theme of creativity features prominently in the Partenariat’s discourse, in reality its projects to date have focused on a narrow range of cultural segments. The illuminated signage and projections flooding the building façades, and the interactive installations such as the swings on Président-Kennedy Avenue and Mégaphone on Promenade des Artistes cannot hide the absence of a true artistic presence, falling short of the organization’s creative aspirations. Spectacular, seductive, consensual, and always in its place, the “culture” of Quartier des spectacles is distinguished above all by the fact that it is predictable, clearly identified, and mediatized enough to provoke neither anxiety nor questioning.

Red Light Monument: Floor area of café cléopâtre stages (500 square feet),

vue d’installation | installation view, esplanade du métro St-Laurent, Montréal, 2012.

Photos : Geneviève Massé © DARE-DARE, permission de L’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Current Trends In Cultural Politics

Isn’t Quartier des spectacles just another place, among many, that we can choose to avoid? Can’t we just leave it to indulge in its latest whims? Even for participants who, like DARE-DARE, choose to get involved with rather than avoid the district, the consequences, in reality, seem very limited. Following the Secondes zones incident, the compromises that the Partenariat expected of DARE-DARE proved similar to the essentially logistical constraints that the centre had had to come to terms with at its previous locations. And yet, unlike the borough councils with which DARE-DARE had to negotiate in the past, the Partenariat is a major player on the Montréal, Québec, and even Canadian cultural scenes, and its approach — despite its efforts to be discreet — reflects the overarching trends in current cultural policy.

The attention that the Partenariat pays to the growth of (carefully planned) interactions between art and public and to the creation of links between art and industry (digital technologies, in particular) is closely aligned with the directions recently taken by various arts councils.11 11 - These directions result from the encounter between two forces with which arts councils have to come to terms: on the one hand, the artists and organizations they support; on the other hand, the governments that determine their budget. In the absence of political mobilization and cohesion among artists and arts organizations, can one really expect that government concerns not play an increasing role in the choice of cultural policies? The Partenariat distinguishes itself, perhaps, in the frankness with which it states the intentions underlying its choices: to secure financing for the arts with immediate, easily quantifiable economic spin-offs (tourism, business) and social benefits (urban renewal, social harmony) — aspects that are already apparent in the Conseil des arts de Montréal’s arts and business program, in the Marois government’s decision to invest in a new digital culture strategy (Stratégie culturelle numérique du Québec) rather than adjusting the budget of the Conseil des arts et des lettres,12 12 - The budget tabled in February 2014 by Québec’s Minister of Finance, Nicolas Marceau, anticipated the injection of $150 million over seven years in the new strategy, while the government abandoned its promise to increase the CALQ’s budget by $13 million. and in a recent speech made by Joseph Rotman, chair of the Canada Council for the Arts: “Artists and arts organizations . . . need to move to the intersection of the arts and the economy, the arts and innovation, and the arts and healthcare, education and social policy — and offer a way to re-imagine Canada’s future as an international leader of the creative economy.”13 13 - Investing in Creativity: A National Priority. Speech by Joseph Rotman, Chair, Canada Council for the Arts, to the Montréal Council on Foreign Relations, November 13, 2013. Full text: http://conseildesarts.ca/en/council/news-room/news/2013/joseph-l-rotman-investing-in-creativity-a-national-priority.

The Question of Satisfaction

According to Dufrasne, the direction taken by DARE-DARE has been received very positively by its sponsors. This level of satisfaction lies, for the most part, in the quality and originality of the centre’s work, but Dufrasne does not deny the fact that the new location and the visibility that it brings have played a role. In the name of good governance, arts councils must demonstrate the effectiveness of their policies, and numbers seem to be the most popular way of doing so. Profitability is no longer measured in dollars alone but also in terms of crowd numbers — an indicator of user satisfaction. The context that sees DARE-DARE — having successfully negotiated its rightful place in the cultural economy — receiving critical praise from its sponsors raises an important question: Who among us, organizations and artists, does not receive such praise?

[Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft]