photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de | courtesy of the artist & Galerie Simon Blais, Montréal

Guy Pellerin’s painting reveals itself in an extremely close relationship with those who engage with it. What is made visible in colour eloquently raises the question of the subject. The source subject — that which is painted — no longer exists, or exists only in absentia. Indeed, what is represented appears as an affect: for Pellerin, colour is the vector of an emotion tied to an intimate experience. One could think of his work as a kind of topography of memory, its loci, its sensations, its vibrations.

In a body of work developed and honed over thirty years, Pellerin has chosen to focus on the surface, a surface that appears, one might say, as the outcome of a process that bares its reliefs and hollows, a kind of mental construction made visible, which acts upon our memory by calling on our experience of colour and its embodiment.

At the very source of Pellerin’s work, colour and its architectural, structured rendering acts as an open referent where various levels of meaning may appear. This practice, wholly directed toward its absent object (that which is in question, that which is drawn from the real remains hidden, unrepresented) points toward sources filtered by memory and presents a subjective inventory to which the artist asks us to acquiesce. What is shown is a proposal, an abstract composition projected from the selected and quite real object. A fantasized reality projected onto surfaces conceived as screens — such a reading easily comes to mind.

The painting can take several forms. In no. 356 – Cathédrale Saint-Charles-Borromée, Joliette (2004),1 1 - Guy Pellerin, La couleur d’Ozias Leduc, Musée d’art de Joliette, Joliette (Québec), September 12, 2004 to February 27, 2005. Pellerin produces a random inventory of the colours present in the canvases of Quebec painter Ozias Leduc. He sets the somewhat faded colours onto monochrome surfaces lined up along the wall, devoid of any referent. Each of the forty-eight components suggests the nostalgic remains of an outmoded past and sustains our memory in its attempt to conjure up the works of Leduc, in whole or in part. Paradoxically, it is through the absolute pictorial practice of the monochrome that his cinema of memory unfolds. The object, the referent on which the collection is constructed, is excluded. With Pellerin, the sign is the trajectory of the perceived colour, ordered and recomposed, or rather, reinvented. He tends toward a recognition in the colour he shapes; he goes to colour to recognize himself through it, to experience it. Again, in no. 309 – La couleur des lieux, Copenhague (1997),2 2 - La couleur des lieux – Copenhague, Galerie Yves Leroux, Montréal, Québec, October 25 to November 29, 1997. Pellerin draws us into a sensitive experience, here based on a location. After an extensive intimate exploration, and by means of a kind of “time regained,” he manages to conjure up his experience of Copenhagen, again, by presenting it as units of colour. Pellerin evinces a manifest desire not just to show colour but to put it on display. On the smooth surface of his eleven monochromes, one can discern reminiscences, repentances — times past — in the layered pentimento of colour applied beforehand. It is a long road to the final colour, one that reveals itself to light and recognition. What is signified is the process undertaken, traces of which become visible materials, inscribed in an implied temporality. Colour is a cognate of the Latin word celare, to conceal, suggesting the idea that colour is what covers and hides the surface of something. Thus, the colour resulting from the process conceals the object (Leduc’s painting) or the location (Copenhagen). In this sense, Pellerin is engaged in a dissimulation of the initial object. One may understand his work as functioning as an organizer of memory — his own — focused on an object of study, which fully plays its role as referent.

© Guy Pellerin / SODRAC (2012)

photo : Patrick Altman, permission de | courtesy of the artist &

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Québec

Another series of monochromes, no. 383 – route 132 (2007),3 3 - Route 132 et autres couleurs, Musée régional de Rimouski, Rimouski (Québec), April 19 to June 9, 2007. presents a colourful array of fourteen circular elements representing selected places along the trajectory of highway 132 between Longueuil and Rimouski. Under each tondo, a label displays information on the time and place of the shot. The text here is a key contextual element of the work and fully participates in establishing a repertoire of places for which colour is the driving force.

Pellerin plays on several levels: by showing things that relate to him through an operative memory, he interrogates the subject (himself) as much as the object (the outcome of the work of memory). The artist is an explorer and his quest directly questions his connection with the real. Yet this quest, is it not pursued in a kind of continuous, endless movement? The subject is always pursuing a shifting identity: “Man was created from nothing. That is why he pursues that nothing, which is nowhere.”4 4 - Ruisbroeck, cited by L. Silburn, “Au-delà de l’Horror Vacui,” in Nouvelle Revue de psychanalyse, Paris, no. 11 (Spring 1975), 47. (Our translation)

In another recently viewed work, no. 390 – Oskar H. Ehrenzweig (2008),5 5 - Tourner autour (Sylvie Cotton, Guy Pellerin, Jean-Benoit Pouliot), Galerie Simon Blais, Montréal (Québec), June 8 to August 6, 2011. Pellerin shows a series of six shipping labels on which he has applied colour taken from a necktie motif painted on cardboard boxes by a major Austrian designer in the 1930s and 1940s. Here, the artist creates a kind of colour lab, preserving a trace of the lid of the container in which he had mixed the colours and placing it on the label where it imprints its memory. This shipping label and circle of colour act as an emblem, or medal, synthesizing the artist’s relationship with the reality of Ehrenzweig’s variously coloured and patterned boxes. By using the labels as supporting medium and preserving the paint lid’s imprint, Pellerin has chosen to embody the colour in the object. Colour has here materialized in the real: the label is no longer an abstract support and the circular imprint instantly refers to the paint lid.

© Guy Pellerin / SODRAC (2012)

photos : Richard-Max Tremblay, permission de | courtesy of the artist & Musée d’art

contemporain de Montréal

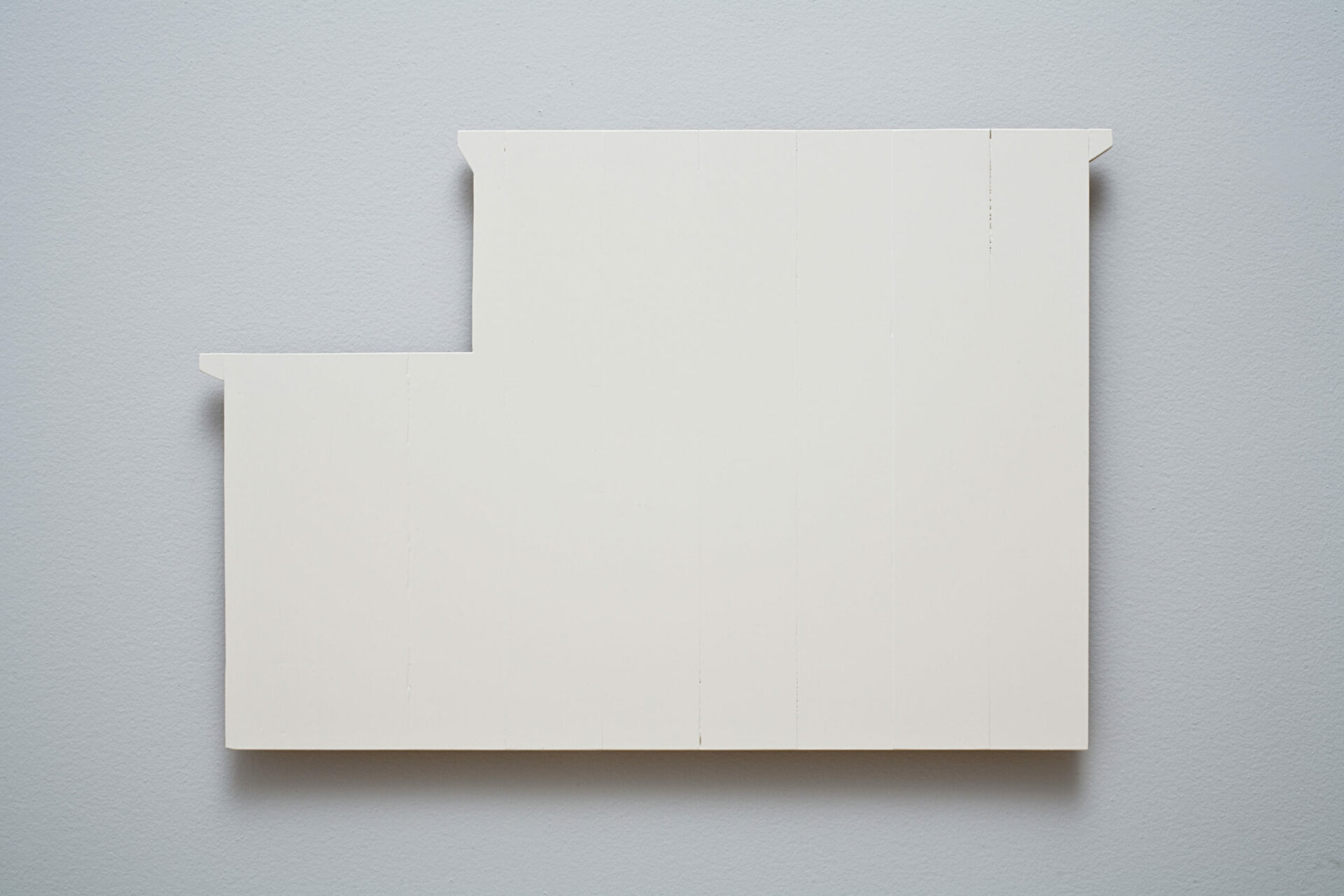

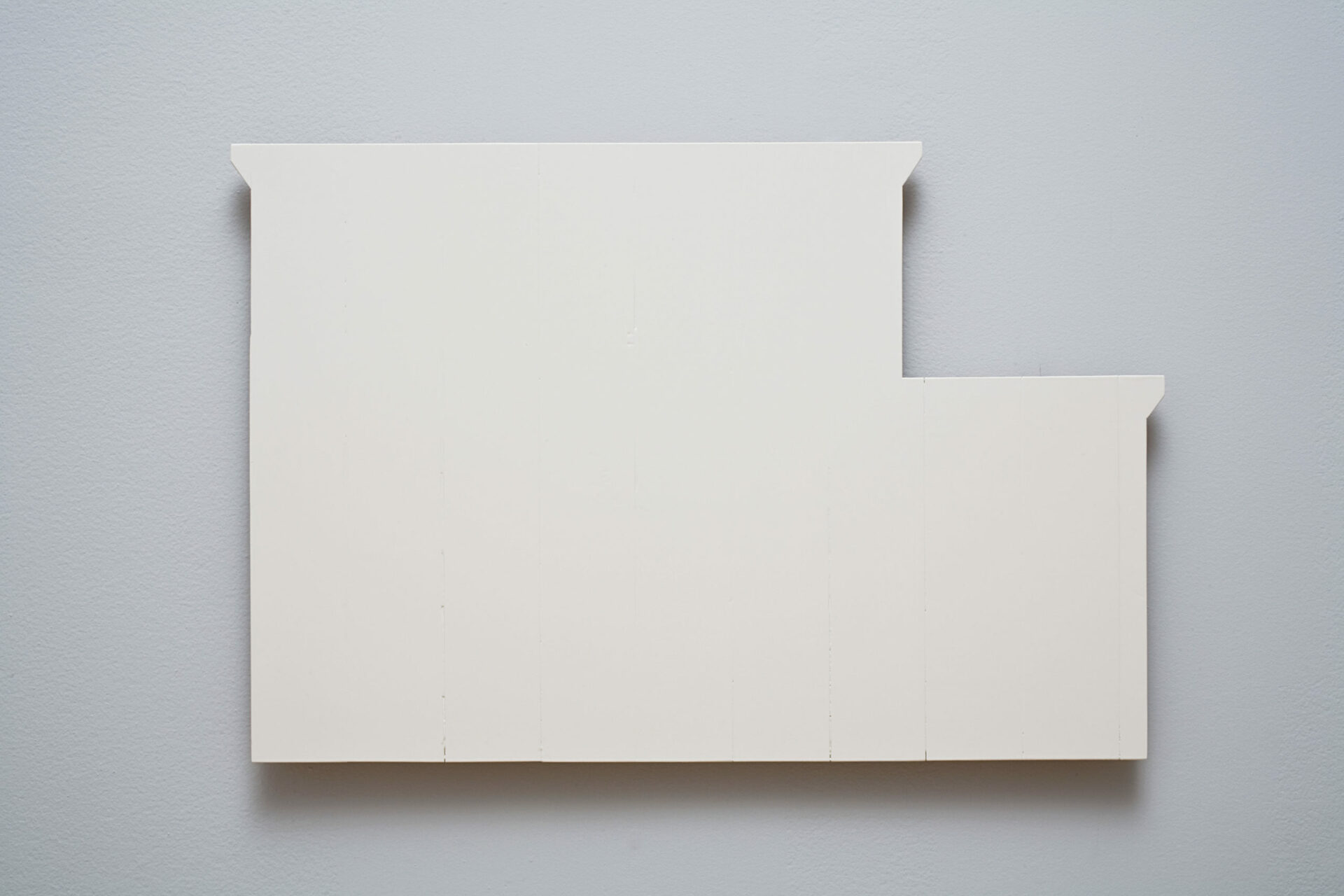

A more recent work still, no. 403 – 621, chemin des Patriotes nord, Mont-Saint-Hilaire, samedi 5 décembre 2009 (2010),6 6 - Borduas: Les frontières de nos rêves ne sont plus les mêmes, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montréal (Québec), April 24 to October 3, 2010. follows a different procedure. Here, he has “figured” the four sides of Paul-Émile Borduas’s house in Saint-Hilaire. With the four lustrous white surfaces, in relief, hung on the wall, Pellerin “draws” or “accounts for” the Automatiste painter’s house. The gesture serves to recreate a private space, taking us on a tour of all its facets. The proposition is thus white… white like Borduas’s paintings, or even, white like Pellerin’s memory of Borduas’s work, registered in his catalogue of sensations and memories.

Pellerin’s oeuvre presents a central paradox. By working on the frontiers of memory, the locus of all sensations, in the nooks and crannies of his consciousness, the artist articulates a proposition at the very limits of monochromatic, repetitive “inexpressionism.” In this, he bases his relationship with the world on an immense conceptual gap between fullness and emptiness.

He appropriates the real, he replicates it, in order to show us the things that inhabit him, presenting us with traces animated by memory and nostalgia. For Pellerin, colour is the gateway between what has been and what is or will be. The work is a reflecting mirror inscribed in time. And time… is always far away.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]