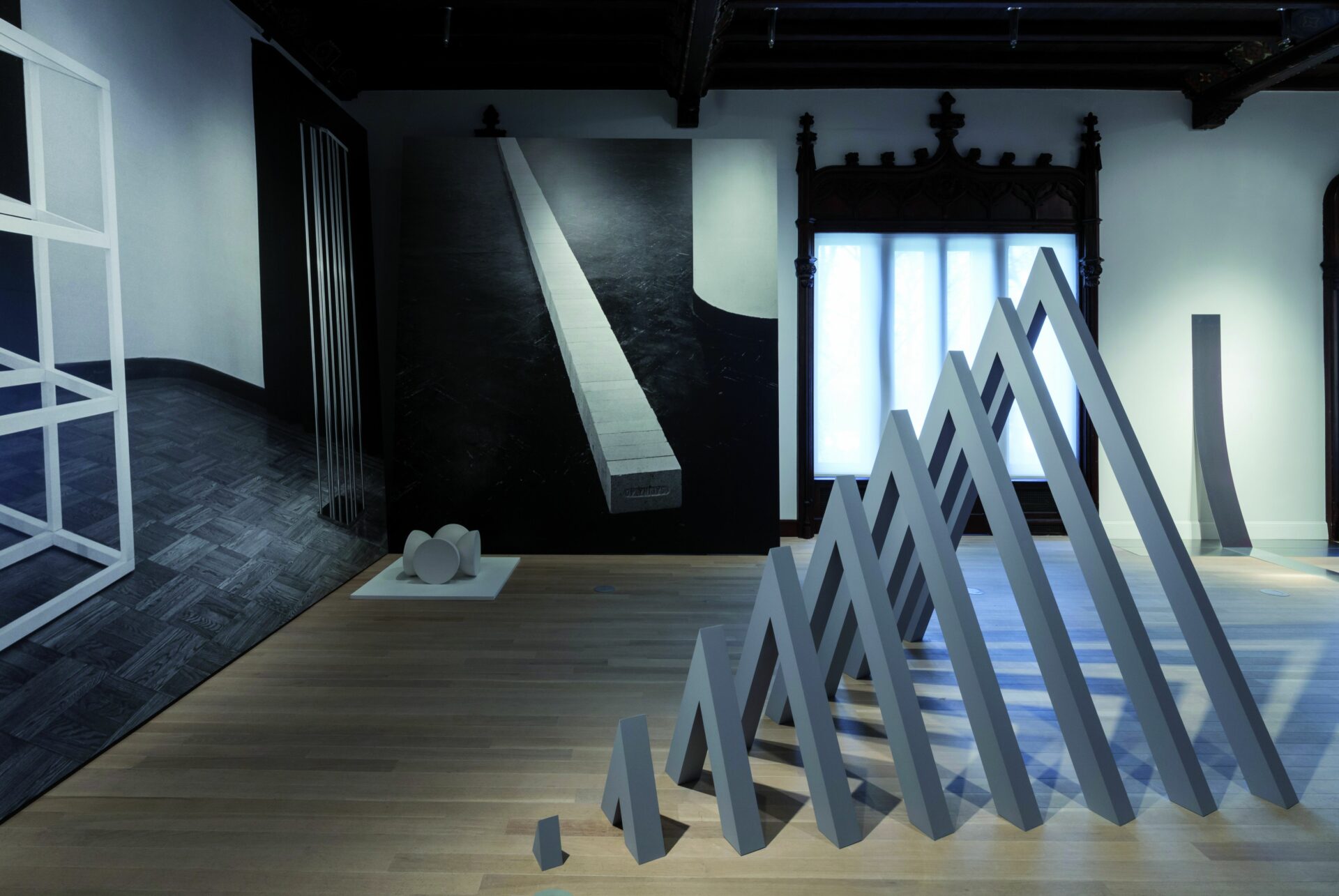

One of the most visible symptoms of the art world’s recent interest in the question of the exhibition can be seen in the proliferation of re-presentations — remakes, re-enactments, transpositions — of all kinds of exhibitions seen as important. Though small in number, they are increasingly discussed and mentioned, which tends to give them a prominent place in representations of contemporary art. The most spectacular iteration is that in which an exhibition is entirely restaged, as in the 2013 presentation of When Attitudes Become Form at the Prada Foundation in Venice (Berne, 1969; Venice, 2013). Leaving aside the significant change of context — the original exhibition was staged in an eighteenth-century Venetian palazzo — the reconstruction was extremely faithful to the original, bringing together many of the same works and artists, in as close an architectural reproduction as possible, and suggesting the works that were missing. The exhibition as a whole thus resembled a new kind of period room, with painstaking attention paid to the least detail (false windows, false plinths, the ordering on the walls, imitation wood floors and tiling, and other elements).

One of the organizers, Germano Celant, stated that he wanted to transform the original exhibition into an object: “In order to become a reflection, the exhibition was given new meaning by treating it as a readymade . . . inserting it as an ‘archeological’ citation into the exhibition spaces of Ca’ Corner della Regina . . . created the same effect as the encounter between a bicycle wheel and a stool in Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913).”1 1 - Germano Celant, “A Readymade: When Attitudes Become Form,” exhibition brochure for When Attitudes Become Form, Bern 1969/Venice 2013, n.p. He also implied that a kind of transcendence might be conceivable in this exhibition: “. . . the operation of reconstructing and one-time restaging When Attitudes Become Form is not connected with a fetishistic and nostalgic dimension, but mirrors a reality that has passed and been erased, yet can still have a significance.”2 2 - Ibid.

Others 1, 2014, installation views, The Jewish Museum, New York.

Photos : David Heald/The Jewish Museum

Others 1 & 2, 2014, installation views, The Jewish Museum, New York.

Photos : Kris Graves & David Heald /The Jewish Museum

Similar concerns had previously been in evidence in the exhibition Vides, in the National Museum of Modern Art at the Pompidou Centre in 2009.3 3 - Vides, MNAM-Centre Pompidou, February 25 to March 23, 2009. Vides was more a metaphorical evocation than a literal reconstruction; the elements of the original presentation were entirely put aside in favour of freeing up a series of uniform empty spaces in the museum. The questions raised were nonetheless not so different from those put forward in When Attitudes Become Form, especially because here, too, a discourse was laid out in a certain number of arguments or examples originating in historic exhibitions. A similar phenomenon can be seen, to various degrees, in a great many exhibitions in recent years, whether an exhibition is remounted in order to complete it, as is the case with Primary Structures (1966) — re-presented in the same venue where it was held the first time4 4 - Other Primary Structures, Jewish Museum, New York, May 14 to August 3, 2014. — or when elements borrowed from this or that exhibition are allusively integrated, as was done in the evocation of a 1959 hanging of works by Julio Gonzalez at documenta (13).

Photos : Attilio Maranzano, courtesy of Fondazione Prada, Venise

Writing Art History Differently

Whether they are evocations or transpositions of past shows, re-presentations have important implications for thinking about art history because they also involve restaging the original contexts for presenting the works as elements signifying a particular history. This phenomenon is part of a well-established general trend whose aim is to reorient art history toward a more general cultural or social history. This trend obviously evinces an important break with the decontextualizing practices of modernist narratives and of the early museums of modern art.5 5 - Regarding the first exhibitions at MOMA, see in particular Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998).

If the situation has changed, it is because, for some time now, the legitimization of historical avant-gardes by bringing them into museum-level institutions is no longer an issue; rather, it is a question of critically revisiting their histories. The re-creation of exhibitions has been part of this process since at least Germano Celant’s Ambiente/Arte at the 1976 Venice Biennale and Pontus Hultén’s inaugural series of exhibitions at the Pompidou Centre (Paris-New York, Paris-Berlin, Paris-Moscow, Paris-Paris [1977 – 81]). In fact, few shows with the intention of providing a historical perspective on modern or contemporary art history haven’t envisaged a more or less elaborate re-presentation or evocation of exhibitions seen as significant. Following this logic, museums and art centres are undertaking more and more research on and evaluation of their own exhibitions.6 6 - For example, this is the case with the Pompidou Centre and its plans to develop a catalogue raisonné of its exhibitions since 2011. See also, for the Magasin de Grenoble, Magasin 1986-2006 (Zurich and Grenoble: JRP Ringier and Le Magasin CNAC, 2006); for the Centre des arts actuels SKOL in Montréal, Les commensaux: quand l’art se fait circonstances, 2001; for the Nouveau Musée/Institut d’art contemporain in Veilleurbanne, Jean-Louis Maubant, ed., Ambition d’art, 2 vol. (Villeurbanne and Lyon: IAC and Les presses du réel, 2008); for the CAPC in Bordeaux, Paul Ardenne, CAPC Musée 1973-1993 (Paris and Bordeaux: Éditions du Regard and CAPC Musée), 1993; for the Consortium in Dijon, Xavier Douroux, Frank Gautherot, and Éric Troncy, eds., Compilation : Une expérience de l’exposition (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 1998); among others.

Re-presenting exhibitions has important implications insofar as artworks are shown not so much for themselves as for the ways in which they illustrate choices: the relationships or historical perspectives on display are deployed by the exhibition organizers rather than the artists. In fact, the increasing importance of this sort of practice, in the context of both permanent and temporary installations dedicated to modern and contemporary artists, reflects the interest of conservators and curators in the central role played by mediators in art history, at the expense of the notions of the artwork’s autonomy and self-referentiality — also borrowed from sweeping modernist narratives.

Photo : Attilio Maranzano, courtesy of Fondazione Prada, Venise

The Canon of Exhibitions

The return, in recent years, to past exhibitions in various re-presentations cannot help but raise the question — a familiar one in the arts — of finding inspiration in a model. Some focus on proximal research (calling to mind the issue of imitation), whereas others work toward creating distance — transposition or transformation — and make space for the expression of the person confronted by the model. It is true that, independent of the question of art history or of the gaze brought to bear by institutions on their own history, restagings of exhibitions presuppose another issue: supplying examples for contemporary curators. The review (sometimes literal) of past shows — an obligatory rite of passage for any young curator — thus takes on a new function: justifying present-day exhibitions through references to earlier ones now seen as exemplary.7 7 - In some cases, such as When Attitudes Become Form, the use of reference seems limitless. See How Latitudes Become Form: Art in a Global Age (Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, 2003); When Speeds Become Form (Seúl, Portugal, 2007); Alter Ego. Quand les relations deviennent formes (Taninges, Chartreuse de Mélan, 2008); When Lives Become Form — Contemporary Brazilian Art: 1960s to the Present (Tokyo, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2008 – 09); Quand les attitudes… (Toulouse, Printemps de septembre, 2009); When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitude (San Francisco, CCA Wattis, 2012); When Contents Become Form (London, Arbeit Gallery, 2013); When Platitudes Become Form (Toronto, Mercer Union, 2013); and others. This question thus presupposes the existence of a canon of exhibitions — that is, a body of shared references, which might serve as a reservoir of models for emerging curators.

It is in this sense that we must no doubt understand the recent appearance of numerous books exploring the history of exhibitions, some of which aim, quite explicitly, to contribute to the construction of such a canon. As the curator Jens Hoffmann writes in the introduction to his book about the most influential exhibitions, “It is impossible for any field truly to progress without understanding its own past.”8 8 - Jens Hoffmann, Show Time: The 50 Most Influential Exhibitions of Contemporary Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2014), 11 – 12. The critic Simon Sheikh remarks that the historicization of exhibitions and the canonization of some of them goes hand in hand with the professionalization of the field of organizing exhibitions — a situation in which exhibition organizers are trained in specialized schools rather than on the job through internships, self-education, or in museums. In fact, from the moment that curatorial education was formalized, its history was necessarily normalized.9 9 - Simon Sheikh, “On the Standards of Standards, or, Curating and Canonization,” MJ-Manifesta Journal, Journal of Contemporary Curatorship, No. 11 (2010 – 11), 15. Thus, the canon has a double role: it is at once a body of references serving as examples for future curators and a repertoire of counter-models against which to position oneself.

The question of establishing a canon is, however, more complex than it seems. The art historian and curator Christian Rattemeyer explains it this way: in addition to the absence of universal reference points in the field, there is neither a terminology nor a descriptive methodology shared by all researchers. Exhibition “genres” are not firmly established and categories allowing one to define what may qualify as innovative or experimental in a project are lacking, as is anything that might distinguish such projects as successes or failures. He asks, “How do we compare different modalities of display, curatorial selections, the changing interactions between curators and artists, expectations for and from the viewers?”10 10 - Christian Rattemeyer, “What History of Exhibitions?,” The Exhibitionist: Journal on Exhibition Making, No. 4 [Berlin, Archive Books] (June 2011), 37.

Photos : Georges Meguerditchian, © Centre Pompidou, Paris

These questions lead to others that refer to the development of an autonomous curatorial field, which we’ve been seeing for the last decade or so.11 11 - On this question see, notably, Beatrice von Bismark, Jörn Schafaff, and Thomas Weski, eds., Cultures of the Curatorial (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012). From this point of view, we might recall that in Pierre Bourdieu’s view a field may also be understood as a game, an understanding of the rules of which is required for those who wish to take part in it: “Through the practical knowledge of the principles of the game that is tacitly required of new entrants, the whole history of the game, the whole past of the game is present in each act of the game. It is no accident that, together with the presence in each work of traces of the objective (and sometimes even conscious) relationship to other works, one of the surest indices of the constitution of a field is the appearance of a corps of conservators of lives — the biographers — and of works — the philologists, the historians of art and literature, who start to archive the sketches, the drafts, the manuscripts . . .”12 12 - Pierre Bourdieu, “Some Properties of Fields,” in Sociology in Question, trans. Richard Nice (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1993), 74.

One must therefore consider, alongside Simon Sheikh, that the question that arises is not so much knowing which exhibition should or should not be part of the canon, but who should formulate that canon. 13 13 - Sheikh, op. cit., 16.Obviously, the matter is not limited to naming individuals. It is also a question of the manner in which this writing issues from an “institutional inscription”: the form of knowledge that legitimizes it and that it addresses.

Translated from the French by Peter Dubé