In 2013, the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) presented the exhibition Sakahàn, a main objective of which was to illustrate the wide aesthetic diversity of international Indigenous art. Another aim was to strengthen relationships among artists, curators, authors, scholars, and the gallery itself to highlight the fundamental and original contribution of Indigenous artists to contemporary art discourse. Launching a five-year dissemination program intended to enable curators to adapt to the changing dynamic of Indigenous art, the exhibition was not intended to be exhaustive; with twenty-four artists on display, it would have been difficult for Sakahàn to have a specific thematic direction unless it was Aboriginal identity itself. As Christine Lalonde, associate curator for Indigenous art at the NGC, noted, “The selected artworks advance the dialogue, not by defining what is (or who is) Indigenous, but by contemplating, as artist and musician Nicholas Galanin expresses it, ‘what it means to be Indigenous in the twenty-first century.’”1 1 - Christine Lalonde, “Introduction,” in Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art, ed. Greg Hill, Candice Hopkins, and Christine Lalonde (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2013), 15 – 16. Although it explores the flexibility and inclusiveness of the notion of “autochthony,” Sakahàn reminds us that this aspect of art history must continue to be written on a smaller scale. Of course, it is important to develop an international community of players in the Indigenous art world, but, in Canada alone, the scope of work that remains to be done is staggering. The case of contemporary Aboriginal art in Quebec is a striking example of the gap that needs to be bridged and at the same time highlights a range of specific epistemological issues.2 2 - This question is the subject of one of the areas of analysis of the Groupe de recherche sur l’art contemporain autochtone au Québec, led by Louise Vigneault, in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Université de Montréal. The hypotheses discussed in the present essay result from work done by this research group.

When one looks at the territorial division of Canada, it is obvious that the borders have no representative value for Aboriginal nations. We have only to think of the Mohawks, who live in communities in both Quebec and Ontario — as well as in the United States — to understand that the arbitrary cartography traced by history has, once again, omitted much. Beyond geographic divisions, Quebec also stands out for its demographics. In comparison, it is likely that Aboriginal communities will form almost one third of the population in Saskatchewan by 2045,3 3 - Government of Saskatchewan, “Aboriginal People,” www.gov.sk.ca/Default.aspx? DN=d35c114d-b058-49db-896a-4f657f5fd66e. and Ontario is home to twice as many Aboriginals as Quebec;4 4 - Employment and Social Development, “Canadians in Context — Aboriginal Population,” http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/[email protected]? iid=36. it is difficult not to envision that these demographics will influence the presence and representativeness of Indigenous art. We can add to this the evident demographic impact of Aboriginals living in urban centres, who are better known as “urban Natives.” The exhibition Beat Nation, first presented at Ottawa’s SAW Gallery in 2009,5 5 - Significantly, before being presented as an exhibition, Beat Nation was a web project organized by curators Tania Willard and Skeena Reece and distributed by Vancouver’s Grunt Gallery. See www.beatnation.org. This multiplicity of distribution platforms fits perfectly with the plurality and mobility of the Aboriginal approach to artistic representation. provides a clear overview of the artistic effervescence arising from the encounter between Aboriginal artists and the symbolic, historical, and — to a certain degree — logistical realities of urban life. In an exhibition targeting the intersection of hip-hop and Aboriginal culture, it was impossible not to include works by young urban artists.

Photo : Vancouver Art Gallery

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Equinox Gallery, Vancouver

Making Claims Differently

Among the artists in Beat Nation, Sonny Assu, an artist of Kwakiutul origin, stands out. Born in British Columbia and living in Montreal, Assu not only exemplifies the difficulty of situating an Aboriginal artist as a function of provincial divisions (the question of whether his work can be labelled Quebec contemporary Aboriginal art becomes almost moot), but reminds us that artists migrate not only from the reserve to the city, but also from city to city. Assu’s work also epitomizes how important it is for many Aboriginal artists to stress the deceptiveness ingrained in “official” history — a version of history that struggles to hide the incalculable injustices of colonialism. The artist plays on references to popular culture, in particular consumer culture and brand images, to highlight the widespread stereotypical vision of First Nations’ identitary heritage. In recent years, Assu has adopted a more conceptual — less ironic or humorous — approach to express, with greater subtlety and force, the identity-related and political content of his critical discourse. Ellipsis (2012), included in the version of Beat Nation presented at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 2013, testifies to this approach to making claims. Few people are aware of the legislative aberrations of the Indian Act (1876) — often “forgotten” in history courses — whose assimilationist objectives were once widely promoted by non-Aboriginal authorities.6 6 - The famous testimony by the deputy minister of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, before the Special Committee of the House of Commons, charged with examining amendments to the 1920 Indian Act, is enlightening in this regard: “I want to get rid of the Indian problem…. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.” Quoted in John Leslie and Ron Maguire (eds.), The Historical Development of the Indian Act (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1978), 114. The 136 copper LP records, arranged on the wall to evoke an upside-down sound equalizer, refer to the number of years that have passed since the statute was adopted, as well as to the silence imposed on the First Nations. This politically engaged work also has a more personal aspect, because it is inspired by the artist’s discovery of more than three hundred recordings of potlatch songs, made for the purpose of anthropological conservation between 1947 and 1953 when these ceremonies were still banned under the Indian Act. Among the singers recorded was Chief Billy Assu, the artist’s great-great-grandfather.

Photo : © Sonny Assu

permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The attention paid by Aboriginal artists to history is not new, and art history sometimes tends to forget this. As Candice Hopkins reminds us, analyses by Hal Foster and Mark Godfrey in the 2000s highlight the archival and historical approach of contemporary artists, many of whom adopt the role of “artist historian.” “Both authors,” Hopkins writes, “were responding to a trend in art, but for Aboriginal artists history has always been at the forefront of contemporary practices, in part driven by specific worldviews: for some the past is inseparable from the present and thus must always be included, for others there is simply so much about the past left unsaid.”7 7 - Candice Hopkins, “On Other Pictures: Imperialism, Historical Amnesia and Mimesis,” in Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art,ed. Greg Hill, Candice Hopkins and Christine Lalonde (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2013), 22.

vue d’installation | installation view, Sakahàn,

Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, 2013.

Photo : Brian Gardiner

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Art Mûr, Montréal

Photo : © Nadia Myre

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Art Mûr, Montréal

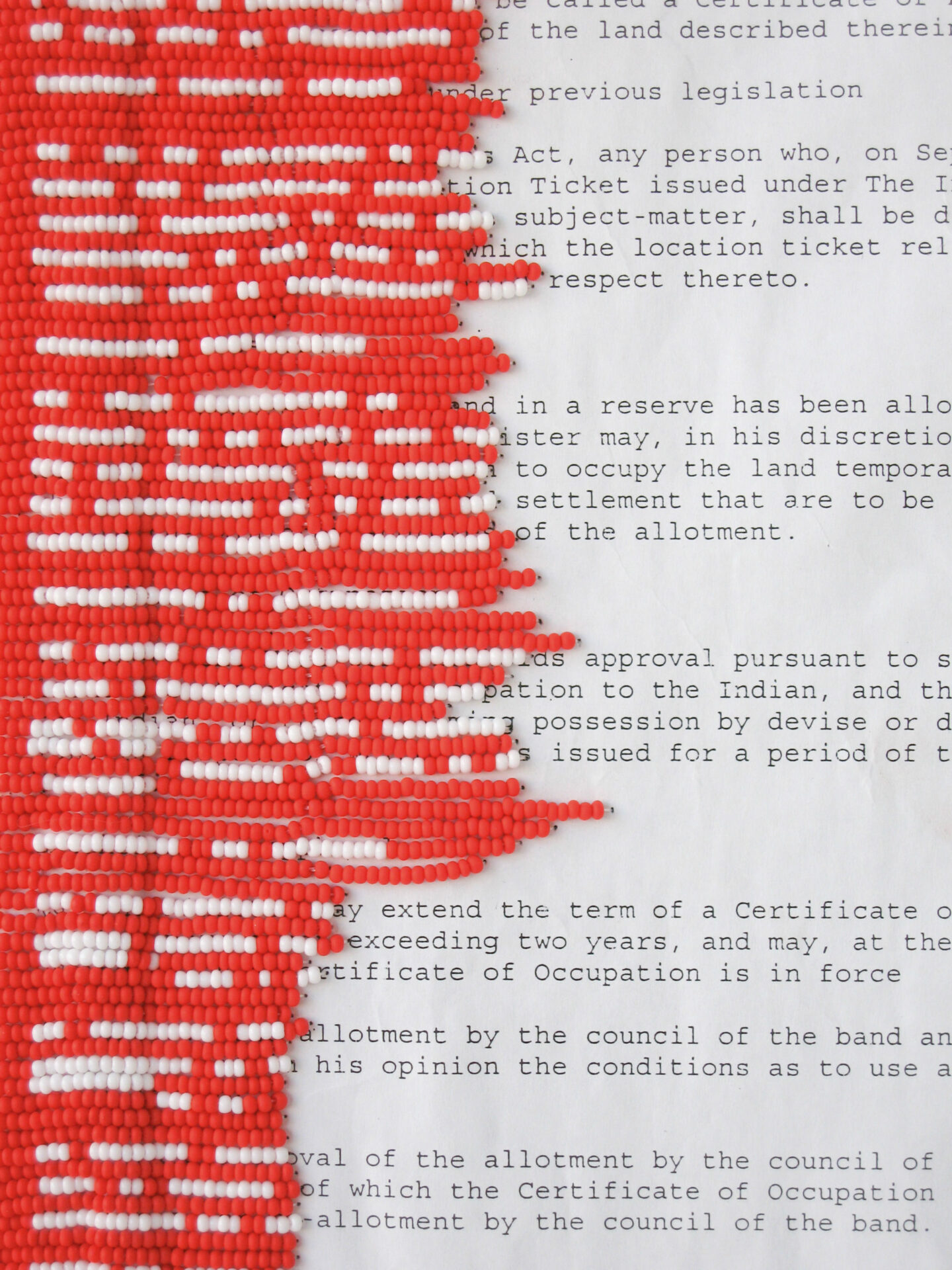

It is not insignificant that more than ten years before Assu, Algonquin artist Nadia Myre expressed a desire to bring back into the historical record the destructive imprint of the Indian Act. No doubt one of her most political works, Indian Act (2000 – 2003) is a community- and process-based project, for which Myre collaborated with more than 250 people to produce a version of the fifty-six pages of the eponymous legislative paper. The collective re-creation of this text was a time-consuming undertaking because, in reality, it meant covering all of the textual content using the traditional technique of beading, involving almost 800,000 beads. The chromatic symbolism was literal: the white beads were superimposed on the text, which stood out against a background of red beads. Colette Tougas accurately analyzes the evocative power of the work: “With its fifty-six black frames now containing abstract variations on red and white, this monumental work manages to deconstruct a social injustice and draw from it an artistically coherent conceptual proposal in which there is a melding between past and present, between ancient technique and contemporary content.”8 8 - Colette Tougas, “Les choses vraies de Nadia Myre,” in Nadia Myre. En[counter]s (Montreal: Éditions Art Mûr, 2011), 18 (our translation).

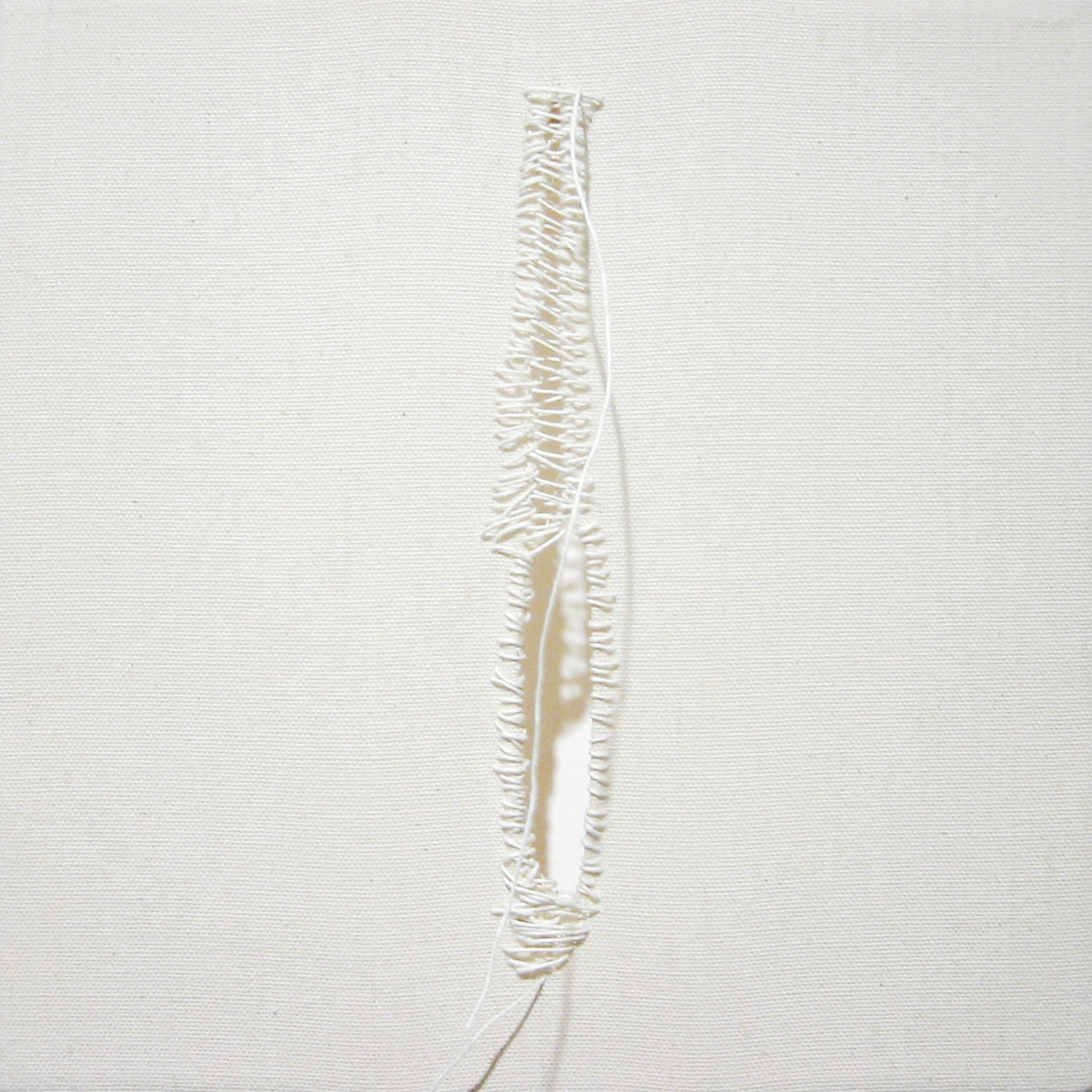

The claims-making approach taken by Myre, who is no doubt the most important contemporary Aboriginal artist in Quebec, always has a personal dimension in the sense that she makes the question of identity — and, more particularly, the identity of Aboriginal woman — one of the springboards for her research.9 9 - The Indian Act was amended in 1985 to strike the clause stipulating that an Aboriginal woman who married a non-Aboriginal lost her Indian status. The question of women’s rights is in this sense closely linked to this legislative document. Like Assu, she uses multiple creative and representational strategies, but her work has a more social approach, which implies encountering the other from a perspective of resilience. In the same way that contemporary “artist historian” trends have long been anchored in Aboriginal art practices, Myre’s community-based approach evades categorization as relational art. In fact, contemporary Aboriginal artists are themselves relational figures, often wearing a number of hats as they write and theorize on the history of their people — and their art history — and work as curators, authors, and voices of their community. One of the projects that is most representative of Myre’s approach, which is both collective and personal, is Scar Project, begun in 2005. During workshops all over North America, Myre invited participants to draw on a piece of blank canvas the scar of a terrible physical, psychological, or spiritual wound. They also had to write a short explanation about this scar and the wound that it covered. As they accumulated, the scars evoked a collective wound. The accompanying gesture of sharing made it possible to think of healing. In comparison, one might advance that this type of dressing a wound is more difficult to perceive in a work such as Rebecca Belmore’s famous Fringe (2008), which, in its way, articulates the figure of the scar; the trickles of blood composed of tiny beads, however, seem to presage a longer and more difficult recovery.

Photo : © Nadia Myre

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Art Mûr, Montréal

vue d’installation | installation view, Smithsonian Institute National Museum of the American Indian, New York, 2010.

Photo : Gavin Ashworth

permission de | courtesy of the artist & Art Mûr, Montréal

Innu artist Sonia Robertson’s works reveal a perspective of resilience closer to Myre’s. Imbued with the artist’s desire to rebalance narrative, historical, political, and identitary disparities, the in situ work Refaire l’alliance, presented in the exhibition Au fil de mes jours, at the Musée des beaux-arts du Québec (2005), measures the critical impact of the updating of ancient techniques, symbols, and knowledge. The multimedia installation evokes wampum belts, hung vertically, on which are projected images of Parc des Champs-de-Bataille and nature scenes that “conjure a vibrant temporal and spatial continuum, from the era before the battles with European armies to the present day.”10 10 - Lee-Ann Martin, Au fil de mes jours (Quebec City: Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, 2005), 43 (our translation). Here again, the socio-political critique is effected through contemplation and introspection, complemented by a soundtrack in which the artist’s voice is mixed with sounds of nature and noises of war. The historical site is thus evoked by multisensorial references, in an obfuscation that refers to the thought patterns of memory. For “remaking the alliance” in no way involves forgetting — on the contrary. Few contemporary First Nations works are not an act of memory, reflecting long-ago events but also the multiple aspects of endemic neo-colonialism. This is one of the few constants in contemporary Aboriginal art.

The symbolic significance of wampum, which had a historically important diplomatic and economic function in North America, was used by Robertson again in 2008 for the celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Quebec City. Sociologist and curator Guy Sioui Durand, a seminal figure in the dissemination and writing of the history of contemporary Aboriginal art in Quebec, was responsible for the part of the event called Rencontre avec les Premières Nations; he invited Robertson and Domingo Cisneros, also a pioneering artist, to participate in the Jardins éphémères project. The critical content of the resulting installation, Wampum 400, responded perfectly to this event commemorating a major turning point in colonialism in Quebec. The artists presented the wampum motif in the centre of a garden in which each plant referred to First Nations. Around the perimeter, a three-metre high chain-link fence, in which the artists created two openings to allow the public to enter, stood as a reminder of colonial oppression and the silence imposed on Aboriginal communities throughout history. Of course, the work is interesting for its content and critical force, but we must not lose sight of the fact that it is an installation-garden: this pushes the question of interdisciplinarity in contemporary art to an interesting edge, forcing us to confront not only what is considered a work of art but also all the stereotypes that continue to face contemporary Aboriginal artists today. This type of work underlines the need to look at Aboriginal art from angles other than those imposed by the structuring discourses of non-Indigenous — or, more broadly, Western — art. Jolene Rickard concurs when she suggests that “there is a need to expand art criticism and visual theory to include a discourse read across indigeneity, colonization and sovereignty.”11 11 - Jolene Rickard, “the Emergence of Global Indigenous Art,” in Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art, ed.Greg Hill, Candice Hopkins and Christine Lalonde (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2013), 54.

Photo : Sonia Robertson

permission des artistes | courtesy of the artists

What this seems to indicate is that it is wise not to draw hasty conclusions about similarities among contemporary Quebec artists of First Nations origin. The difficulty arises not only from the specificity of Quebec, of which I have outlined some problematic features above, but from the need, in this area of research, to increasingly call on approaches that originate from within First Nations — that is, reflect Aboriginal epistemological perspectives. If we change our usual methodological approach, resist our tendency toward rigid categorization, and open our research to a new, more empathic and dialogic approach, several answers will follow.