In recent years, artists, curators, and museums have been using exhibitions as sites of unprecedented exploration. This essay brings together, in fragmentary form, a series of strategies and examples that are helping to redefine the exhibition. Although the different modalities discussed here seem to have little in common at first glance, seeing them in relation to each other gives an indication of the extent to which the exhibition — its functions, mechanisms, discourses, and histories — is now the subject of examination and critical reflection. Where and when did this reflection originate? Although this question is worth asking, given recent histories of exhibitions1 1 - See these two fundamental books: Bruce Altshuler, ed., Salon to Biennial – Exhibitions That Made Art History. Vol. I: 1863 – 1959 (London: Phaidon, 2009); and Bruce Altshuler, ed., Biennials and Beyond – Exhibitions That Made Art History, Vol. II: 1962 – 2002 (London: Phaidon, 2013). and the attempts to theorize their different models2 2 - See, notably, Jérôme Glicenstein, L’art : une histoire d’expositions (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, “Lignes d’art” series, 2009)., the contribution that I wish to make here is concerned less with providing a historical or theoretical perspective, than with describing different approaches. I thus offer a sort of inventory, without considering linearity or chronology, of seven ways in which artists, curators, and museums are rethinking the exhibition. The title of this article, “Exhibition2,” emphasizes how current experiments are being challenged and their self-reflexive dimension, as much as it stresses the importance of this emerging area of study. In other words, the idea of this inventory is to show the potential for questions that the exhibition raises today.

1. Artwork as Exhibition

These days, with artists attaching as much importance to the conditions under which their works are presented as to how their works are produced, the boundaries between artwork and exhibition are often difficult to discern. Le discours des éléments (2006), by the BGL collective, is a case in point, as it pushes the relationship between the two to the limit. It is one of the most challenging contemporary installations in the National Gallery of Canada’s collection. Bringing together ten works produced during the collective’s early years, between 1996 and 2006, as well as a panoply of studio materials and sundries, this vast installation held the artists’ first “retrospective” exhibition.3 3 - Here is a non-exhaustive list of the artworks, elements, and project models produced between 1996 and 2006 that are contained in Le discours des éléments: the motorcycle from and video of the performance Rapides et dangereux (2005), a stuffed moose (Venise, 2004), various pieces of hand-sculpted wood (two from the phone booths of Rejoindre quelqu’un, 1999), many of the boxes and gift wrappings from À l’abri des arbres (2001), the car made of wood and cardboard from La guerre du feu (2006), the wooden framework from Chapelle mobile (1998), Bosquets d’espionnage (2004), Le pouvoir de la fuite (2005), and Marche avec moi (2003); there are also the remains of burned wood sculptures, materials of all sorts, and paint cans heaped pell-mell on the shelves. It is not only one of BGL’s most complex works, but one of the most difficult to inventory and re-exhibit. Its form resembles a warehouse space and museum’s storage area, where works are crammed together on shelves on either side of an aisle. Le discours des éléments is also typical of how the collective recycles and reuses materials, as well as its own works, always reserving the possibility of reorganizing and reconfiguring them in response to the exhibition space. The different elements may also be presented as a single installation or separately as autonomous works. By assembling the first ten years of its production in this way, BGL reiterates and transforms the conventions of the retrospective and encourages the museum to review its acquisition, documentation, and exhibition norms.

Le discours des éléments, 2006, installation view, Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Ottawa.

Photos : © MBAC, courtesy of BGL, Parisian Laundry, Montréal & Diaz Contemporary, Toronto

2. Exhibition as Artwork

The inverse is also possible. A number of artists conceive of the exhibition as an artwork in itself. Since Entre chien et loup, presented by the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris at the Couvent des Cordeliers in 2004, Anri Sala has been reflecting on the exhibition format as a function of the relations between the works and the spectator’s experience.

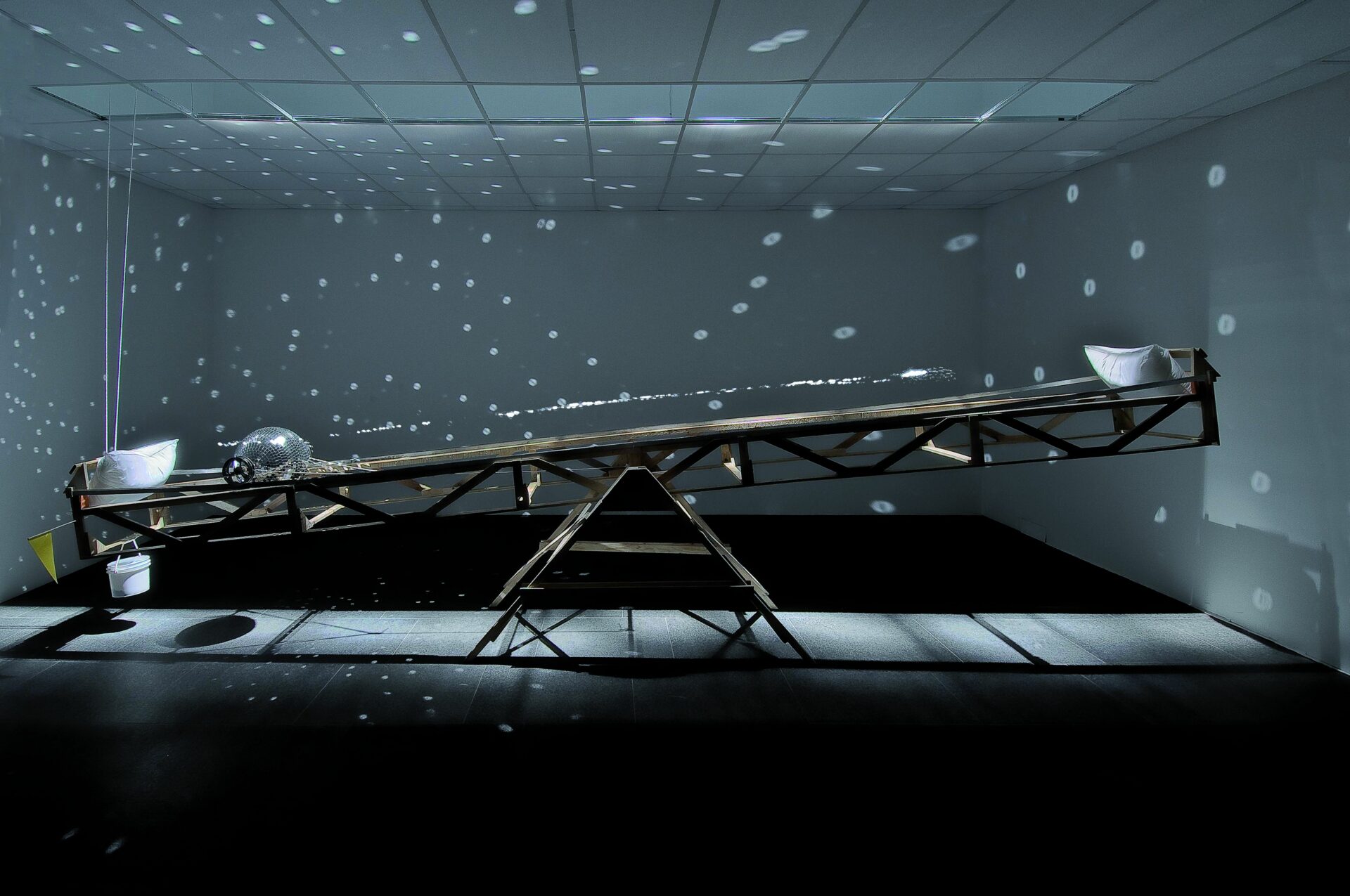

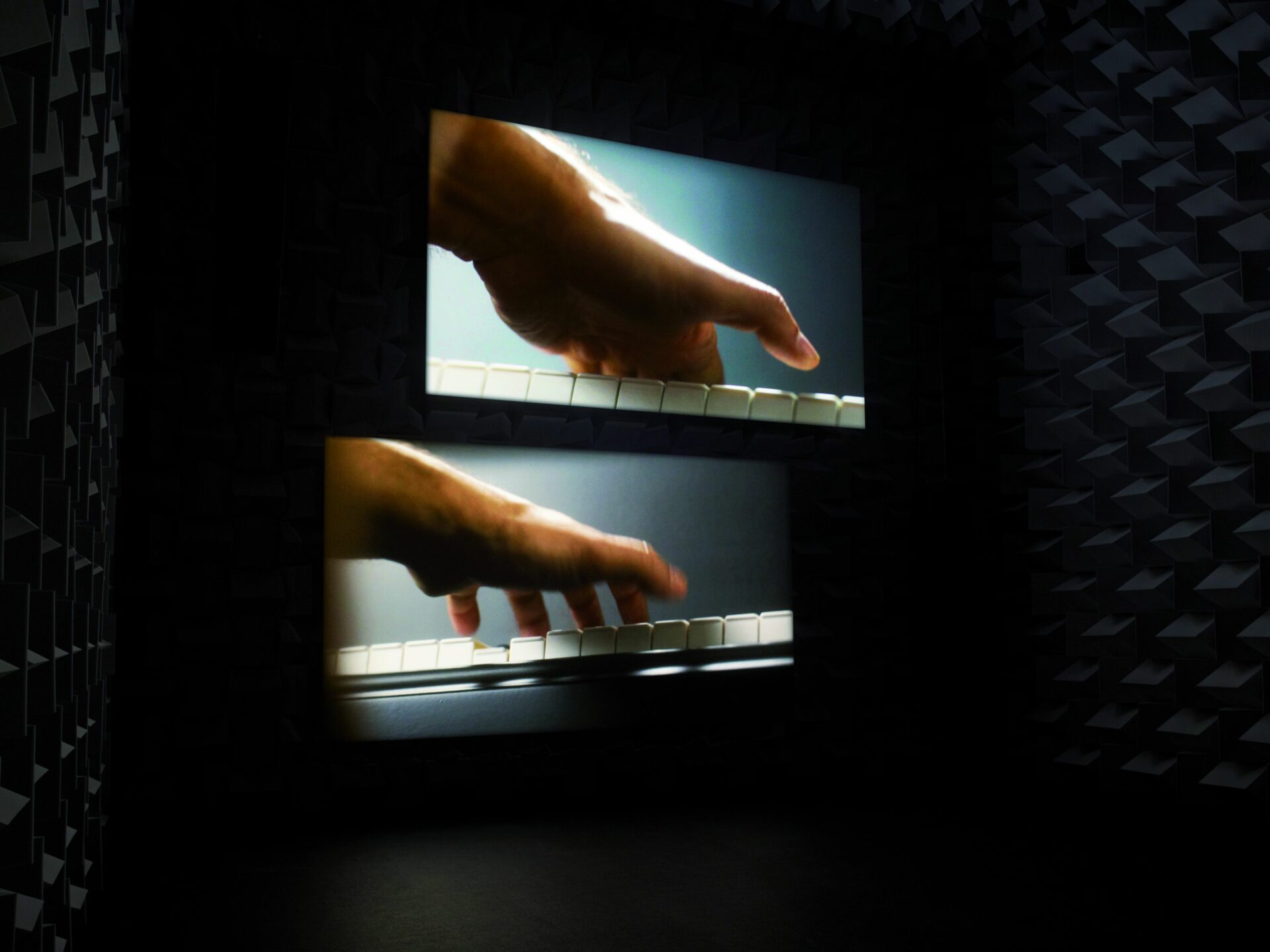

For Sala, the exhibition has become the site of an exploration of space and time. Conceived originally for the Museum of Contemporary Art of North Miami in 2008, Purchase Not By Moonlight brings together a group of works placed sequentially. The exhibition may also be integrated into another exhibition, as it was at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 2010. Sala explores the relations among artworks through alternating sounds and images that synchronize the artworks with one another, just as a musical score shows the contribution of each instrument in the orchestra separately even as it combines them into a single composition. The works thus resonate as much with each other as with the venue. Ravel Ravel Unravel, presented at the 55th Venice Biennale, made use of a similar device. Integrating the space and the acoustics of the German pavilion,4 4 - It should be noted that France and Germany had exchanged pavilions. Sala officially represented France, even though he had designed Ravel Ravel Unravel for the space in the German pavilion. which comprises three rooms, Sala synchronized three interpretations of Maurice Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand, composed in Vienna between 1929 and 1931 for the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, brother of language philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Ravel Ravel Unravel, 2013,

installation view, French Pavilion, 55th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia.

Photo : © Marc Domage, courtesy of Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

3. Exhibition as Exhibition

Today, artists use a countless variety of mechanisms to present objects, mises-en-scène, and reconstructions — for instance, Mark Dion’s archaeological showcases, curiosity cabinets, and reconstructions of explorers’ and scientists’ laboratories; Laurent Grasso’s Uraniborg, inspired by period rooms; Marcel Dzama’s dioramas; and Claudie Gagnon’s tableaux vivants, which literally “perform” historical works. In appropriating modes of presenting knowledge that were developed by museums, these examples all offer a look back at history. Recently, artists have reconsidered modernist models. This is the case, notably, for Luis Jacob, who, with Tableaux: Pictures at an Exhibition (2010), presented a mise en abîme — an exhibition within an exhibition — by constructing a white cube in the industrial space of the Fonderie Darling, in Montréal. The cube, which had one glass wall, offered all the conditions necessary for aesthetic contemplation: a carpet covered the floor, a neutral lighting system illuminated the room, and a bench placed right in the centre of the space encouraged the spectator to look at a series of twelve monochrome paintings hung on the white walls. Here, Jacob exposes the modernist tradition to its own visual device, to its own spectacle: on the one hand, monochrome painting; and on the other the white cube, which Brian O’Doherty described as the central complement to the modernist painting — “unshadowed, white, clean, artificial.” 5 5 - Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 15. The painting and the exhibition are reduced to their simplest expression. The spectator is trapped within this mise en abîme and becomes, in turn, an object of aesthetic contemplation. The modern exhibition space thus becomes the site of a critical reflection on the conditions of the gaze.

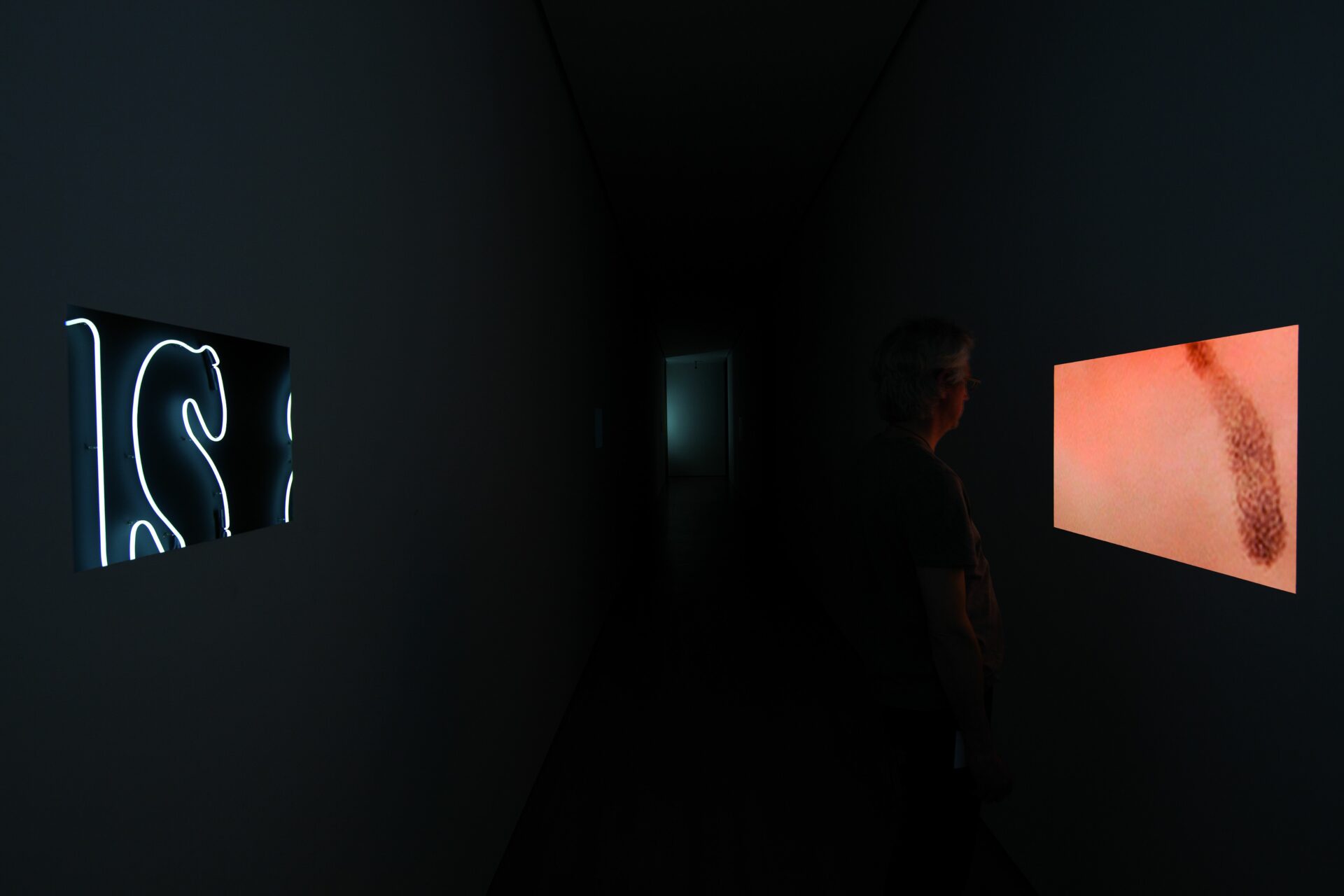

Uraniborg, 2013,

installation view, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. © Laurent Grasso / SODRAC (2015).

Photo : Guy L’Heureux

Tableaux vivants, La Fonderie Darling, Montréal, 2010.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux

La Verdad Está Muerta / Room Full of Liars, 2007.

Photo : courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London

4. Collection as Exhibition

Since the 1980s, museums have increasingly tended to abandon the development and display of their collections in favour of programming temporary “blockbuster” exhibitions that raise attendance numbers. A number of art historians and museologists claim that economic and political imperatives are causing museums to turn to the spectacular and event-based shows. Yet it is clear that this model doesn’t always fulfil its objectives. Some museums have instead begun to update, sometimes radically, how they exhibit their collections. A great number of artists have performed interventions in collections since Andy Warhol led the way with Raid the Ice Box (1969 – 70) at the Rhode Island School of Art and Design. Other striking examples are Joseph Kosuth’s The Play of the Unmentionable (1990) at the Brooklyn Museum, and Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992) at the Maryland Historical Society. Artists propose a reorganization of collections that pays no attention to period, style, aesthetic issues, media, categories, or even proper names and the canons of art history. In doing so, are the museums involved trying to change their relationship with history and broaden the comprehension of art to encompass contemporary issues, including socio-political questions? Not only does this new redeployment of collections change our understanding of art and its place in history, it also transforms the museum and its potential.

In her short book Radical Museology, or, What’s “Contemporary” in Museums of Contemporary Art?,6 6 - Claire Bishop, Radical Museology, or, What’s “Contemporary” in Museums of Contemporary Art? (London: Koenig Books, 2013). Claire Bishop cites the series of exhibitions that the Van Abbemuseum, in Eindhoven, grouped together under the title Play Van Abbe, between 2009 and 2011, as an exemplary case of radical museology. Focused on exhibitions and models of staging rather than on individual artworks, this program adopted an approach that enabled the museum to look back at its history. How was the museum positioned in history, aesthetically and politically? What stories had it told, and how? Among the different series of exhibitions mounted by the Van Abbemuseum, Time Machines (2010) seems the most relevant to the present inventory. As Bishop notes, it reveals the institution’s ambition to become a “museum of museums” or a “collection of collections.”7 7 - Ibid., 29 – 35. Every possible “re-” strategy was central to this project: re-exhibition, reconstruction, re-enactment. Without going into all the details of this complex program, some particularly striking examples are the presentation of archives from the exhibition Degenerate Art (1937) and the reconstruction of artists’ environments such as El Lissitzky’s Proun Room and Abstract Cabinet (1927 – 28). One of the series, titled “The Politics of Collecting — The Collecting of Politics,” included one of the most hazardous projects produced by a museum in recent decades or, indeed, the last century: putting one of the collection’s masterpieces (Pablo Picasso’s Bust of a Woman) on display in the heart of a conflict zone — in Ramallah, in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Proposed by the artist Khaled Hourani, director of the International Academy of Art Palestine, the exhibition Picasso in Palestine (2011) is no doubt one of the most remarkable examples of radical museology imaginable not only because of the risks incurred by the museum, but also for its political, diplomatic, and military impact.

Part 2: Time Machines, 2010, installation view, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

Photo : Peter Cox, courtesy of Archives Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

5. Exhibition as Reconstruction

The reconstruction or re-enactment of artworks, exhibitions, or display of a collection is currently being explored by artists, curators, and museums as a strategy for re-exhibiting artworks with ephemeral origins, but also for bringing history into the present.8 8 - See, for instance, Elitza Dulguerova, “L’expérience et son double: Notes sur la reconstruction d’expositions et la photographie,” Intermédialités: histoire et théorie des arts, des lettres et des techniques, no. 15 (spring 2010): 53 – 71, accessed in Érudit, March 1, 2015, www.erudit.org/revue/im/2010/v/n15/044674ar.pdf; Reesa Greenberg, “‘Remembering Exhibitions’: From Point to Line to Web,” Tate Papers, no. 12 (October 1, 2009), accessed March 1, 2015, www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/remembering-exhibitions-point-line-web; “Re-enactment” special section, esse, no. 79 (Autumn 2013): 2 – 59. Without wanting to trace their history (a subject that has not been studied until now), it is important to note that the first reconstructions by museums apparently go back to the 1960s — even though certain devices, such as period rooms, dioramas, and tableaux vivants, may be considered historical restagings dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Van Abbemuseum was apparently the first institution, in the 1960s, to develop a program aimed at reconstructing artists’ environments and experimental exhibition spaces. Under the direction of Jean Leering, the museum reconstructed Lissitzky’s Proun Room (1923/1965) and László Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modular (1923 – 30/1970).9 9 - We should note one of Claire Bishop’s early attempts, described in, “Reconstruction Era: The Anachronic Time(s) of Installation Art,” in When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013 (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2013), 429 – 50. The artist Sophie Bélair Clément became interested in this phenomenon by working on the reconstruction of reconstructions based on the archives of museums that, since the Van Abbe, have produced different versions of Lissitzky’s Proun Room. Her work traces the process through which the exhibition is made: first, she reconstructs the space but leaves it empty; then she displays one of Lissitzky’s paintings from the collection of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal outside the gallery; and finally, she makes the documentation and correspondence with the museums’ curators and archivists accessible. The title is a description of this process: Salle Proun: mur, bois, couleur, 1923 (1965/1971/2010). Bélair Clément thus re-enacts the history of this artwork through its re-exhibitions.10 10 - Jean Leering (director of the Van Abbemuseum from 1964 to 1973) made the first reconstruction for the exhibition of Lissitzky’s works using a lithograph, a painting, a few photographs of the space, and one of the elements from the space (the only one that hadn’t been destroyed after the Berlin exhibition). In 1970, Leering decided to create a second reconstruction because the work had been requested for loan to two exhibitions, one in Paris and the other at the Tate in London. This version, however, was never presented in the exhibition Art in Revolution in London, because the USSR government refused to lend its works if Proun Room was presented. In 1995, the first reconstruction was sold to the Berlinische Galerie – Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Fotografie und Architektur in Berlin by the Van Abbemuseum. The second is still in the Van Abbemuseum’s collection. This information is available online at www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/replicas-and-reconstructions-twentieth-century-art.

Proun Room, 1923, installation view, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 1971.

Photo : Peter Cox, courtesy of Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Salle Proun : mur, bois, couleur, 1923 (1965/1971/2010), 2011, installation view, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Photo : Richard-Max Tremblay

It was the controversial presentation of Marina Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim Museum in 2005 that drew the attention of critics and art historians to the scope and potential of reconstruction. This raises a series of questions concerning both the work in itself and the status of the exhibition and its author, and their place in art history, as is the case with the restaging of the cult exhibition by Harald Szeemann, When Attitudes Become Form: Berne 1969 /Venise 2013, at the Prada Foundation in Venice in 2013.

An Immaterial Retrospective invite à réfléchir sur ce que sont une exposition rétrospective et une biennale internationale. Elle présente autant des œuvres iconiques que controversées, censurées ou marginalisées, sans prendre en considération la dimension chronologique et les temps forts de cette biennale.

6. Exhibition as Performance

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s exhibition Une rétrospective (tomorrow is another fine day) (2004 – 05), presented at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (Rotterdam), the Serpentine Gallery (London), and the Couvent des Cordeliers by the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, offered an almost empty exhibition space. This first retrospective of the artist’s work featured neither objects nor archives, but spaces in which some of his major works were described and played by “actors.” It was also the first time, to my knowledge, that curators tackled a retrospective for an artist whose relational and collaborative approach required a complete rethinking of the exhibition format. Here the curators had to consider the site’s architecture, the spectator’s engagement, the immaterial and performative dimension of many of the artworks, and the artist’s participation at every stage of the process.

An Immaterial Retrospective of the Venice Biennale, Romanian Pavilion, 2013, reconstitution of The Last Riot (AES + F), 2007, Russian Pavilion t (AES + F), 2007, 52nd International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale.

Photo : Eduard Constantin, courtesy of the artists

Presented in the Romanian pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale, in 2013, the exhibition An Immaterial Retrospective of the Venice Biennale, by artists Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmus, is another example of a retrospective that was impossible to produce or even conceive of. The performance presented fragments of the history of the Venice Biennale in a completely empty space. The works of artists who had participated in the Biennale from its formation in 1895 through to its 2013 edition were presented by five “performers.” For each work, an actor announced the title and the creator, as well as the year it was produced and the year it was presented at the Biennale. An Immaterial Retrospective was an invitation to reflect on the nature of the retrospective exhibition and the international biennale. It presented works that were both iconic and controversial, censored, and marginalized, without taking into account the chronological dimension or the high points of the event. Among the hundred artists whose works were reconstructed immaterially were Picasso, whose painting Guernica had been exhibited in the Spanish pavilion in 1976; Hans Haacke, in the German pavilion in 1993; Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in the American pavilion in 2007; Santiago Sierra, in the Spanish pavilion in 2003; as well as Joseph Beuys, Daniel Buren, Maurizio Cattelan, and Mona Hatoum.

7. Exhibition as Ecosystem

This seventh and last example may seem to diverge from the previous examples, but by bringing together objects, living beings, and organic matter it is the one that pushes the boundaries of the exhibition the most, in terms of the relationship between space and time.

In 2013 – 14, the Pompidou Centre presented Pierre Huyghe’s first retrospective — an artist who has been reflecting not only on the status of the artwork but also on the exhibition arrangement since the 1990s. Featuring some fifty works, Huyghe had conceived of the exhibition as an ecosystem — a living space within the museum, in continuity with what had always fascinated him: “Constructing situations that take place in reality.”11 11 - Emma Lavigne and Florencia Chernajovsky, “Pierre Huyghe,” Centre Pompidou, accessed March 1, 2015, www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/resource/c9nnKkx/rB9r49. The Pompidou Centre had been extended toward the exterior in order to create a space in which living artworks, organic and climatic, could exist in their own reality: bees, ice, water, fog. Inside, a white hare with pink paws wandered among the works and the visitors, and a colony of ants and spiders inhabited the site — despite the risk that the presence of these denizens of the animal world held for the museum. In Huyghe’s view, these beings “bring into this space, designed to separate the living from fixed, something uncontrollable that isn’t played. Animals have their writing, falsely random, and [he has] a greater and greater desire to exploit it.”12 12 - Ibid. He reconfigures his works, creates organic relations among them, and places visitors in the middle of this ecosystem in transformation. The roles and the “actors” are interchangeable. The exhibition is a world-in-becoming: a situation that mingles with real life, has its own rules, is self-generating, and changes over time and in space according to a new rhythm. It is in constant evolution. Huyghe expresses the reversal that is produced within the very experiment that he proposes to us: “It’s not a matter of showing something to someone so much as showing someone to something. . . . I try to work the space like an organism: it is not so much the objects, the elements, but instead the flow, the interplay arising between the elements.”13 13 - Ibid.

Pierre Huyghe, 2014-2015, exhibition view, Centre Georges-Pompidou, Paris. © Pierre Huyghe / SODRAC (2015)

Photos : Ola Rindal & Pierre Huyghe (haut gauche), courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Translated from the French by Käthe Roth