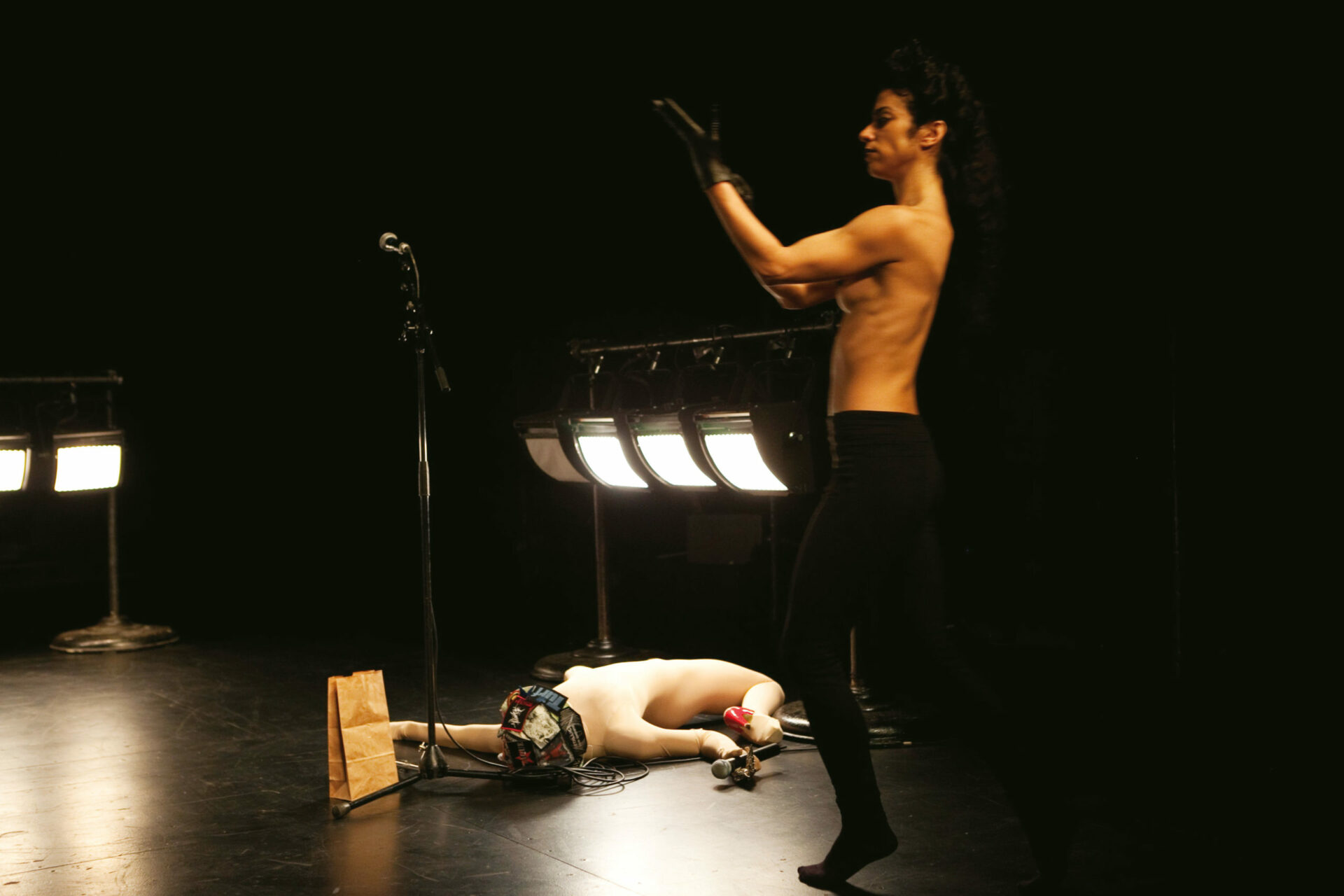

(M)imosa, Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church, 2011.

Photo : Paula Court

Today, voguing is popular thousands of kilometres away from its place of inception; namely, the underground theatres of Harlem where, in the mid-1960s,1 1 - According to some specialists, voguing may have originated in the 1930s in the decadent parties held in such Harlem theatres as the Elks Lodge and the Rockland Palace. See Chantal Regnault, Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989 – 92 (New York: Soul Jazz Books, 2011). heavily made-up “queens” and other LGBT performers (lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender individuals) struck highly stylized poses inspired by Vogue magazine. At these vogue balls, where dance, fashion, and pop music2 2 - House music defines this style as of the 1980s. flourished together, local stars aspired to shine on the stage of the international fashion scene. Over the years, some certainly earned their share of the spotlight thanks to the culture of music videos. However, the majority succumbed to the AIDS crisis and were never able to witness vogue’s emancipation.

At the time, no drag queen could have imagined that a contemporary dance/performance show inspired by voguing would ever become a glittering success on the world’s leading stages. Recently, one show, Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church by New York choreographer Trajal Harrell, was able to accomplish this unexpected feat. The work (which circulates in several versions) has inflamed large audiences from Montreal’s Place des Arts (where a medium-length version titled (M)imosa3 3 - (M)imosa was presented in 2012 at the Cinquième salle de la Place des Arts during the Festival TransAmériques (FTA). was presented) to the Théâtre national de Chaillot in Paris. Harrell can proudly claim to have fulfilled the ultimate dream of the legends of vogue: to make the City of Lights — the cult destination of haute couture — “burn” by dazzling it with talent and eccentricity. Watching this excessive, carnivalesque androgynous work is a breathtaking experience. Audience reactions range from roaring laughter to suppressed shouts, but most pay heed to the decorum appropriate to such bastions of the cultural establishment. Through a series of one-(wo)man shows, incredible performers such as Cecilia Bengolea, François Chaignaud, Marlene Monteiro Freitas and Trajal Harrell, attempt to convince the public that they are the real Mimosa. Their fervour is as hilarious as it is relentless. By alternating between histrionic dance sequences, romantic songs, tear-jerking narratives, and pageants, they appropriate the identity of an unknown character. Their zeal is the only measure of their authenticity.

(Re)performing History

Voguing has withstood the winds of time to claim its place in the dominant narrative of dance history, which until recently tended to sideline it to the generic category of “the postmodern.” Harrell’s work (M)imosa, subtitled Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church, hinges on a hypothetical historical confrontation: what would have happened back in 1963 if black and Latino performers from the vogue scene had befriended the dancers of the Judson Church?4 4 - See Harrell’s website: http://betatrajal.org/home.html. The latter, a progressive New York church, opened its doors to a group of postmodern American dancers and choreographers who sought to create works in a collegial manner. Their aim was to democratize the body, to overcome the “fourth wall” of traditional theatre, and to give rein to chance: ultimate liberation for dance from the last shackles of virtuosity, formalism, and institutionalism.

Paris Is Burning references a well-known documentary film by Jennie Livingstone that demystifies the practice of voguing.5 5 - See Jennie Livingstone’s documentary film Paris Is Burning (1990). Its title refers to René Clément’s 1966 movie Paris brûle-t-il? (Is Paris Burning?) which deals with the Franco-American Liberation of Paris. The film candidly invites us behind the scenes of the vogue ballrooms and for the very first time affords a voice to the leaders and “children” of the most famous vogue “houses”: the House of LaBeija, the House of Xtravaganza, and the House of Ninja. Paris Is Burning is both sweet and sour in tone: voguers are cast as both talented, touching artists and excessive characters with irrational aspirations. Creating a sense of unease, the film cruelly foregrounds the social implications of the vogue phenomenon: racism, homophobia, and ghettoization. (M)imosa’s corrosive wit barely conceals the bitterness that follows humiliation: the taste for luxury without the means to acquire it, the loss of family values, and excessive spectacle as a means of survival.

(M)imosa is a futuristic work; it is history gone wild without a conclusive ending. Transposed into the world of vogue, the values of the Judson Church suddenly take on an androgynous aspect, thus keeping the normative at bay. Although Harrell is indebted to postmodernism, he somewhat rebels against it: the over-inflated egos and hyper-visible, frenetic spectacle of (M)imosa clash with the “flattened” democratic ethos of postmodernism and its highly conceptual European legacy. In response to Steve Paxton, a key figure of postmodern dance who once stated that “No one has ever rebelled against us,” Harrell foregrounds the sensational: when dancer Marlene Freitas (who impersonates Prince) bounces off the stage and rides a member of the audience in an offbeat rodeo routine, no one is concerned that the fourth wall has been broached; rather, the audience is fascinated to discover that a “fifth” wall exists: namely, the intimate space of the spectator. Here, masquerade de-territorializes and de-intensifies dance from choreography — and, conversely, makes the following questions sound radically sterile: “Is this really dance? Is this really choreography?”

(M)imosa, Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church, 2011.

Photo : Paula Court

The 1990s Troubled by Gender

In the early 1990s, voguing was made famous through Madonna’s song and music video “Vogue,” at a time when a new generation of voguers were transforming the style into a dance.6 6 - They were inspired by the spirit of famous dancer Willie Ninja, whose numbers combined poses inspired by magazines, hieroglyphs, and urban dance, among others. Since then, vogue is no longer the property of the black and gay countercultural movement. Although it has left the underground, vogue continues to pay tribute to the legends that originally inspired it. Now embraced on every continent, vogue’s modus vivendi still remains the same: to “be real,” to “give it all you’ve got,” but above all, to “become somebody” while the audience watches on with playful yet critical eyes. For vogue was never merely an extravagant glamour pageant or a masquerade of sequined and heavily made-up bodies: it is a performative ritual in which polymorphous identities are asserted and confronted. Be it in red velvet ballrooms, on the stages of major theatres, or in dance schools in Russia or Japan, vogue now follows an open-ended trajectory, transforming as reluctant purists look on with nostalgia.

The rise of gender studies has also contributed to the rapid expansion of voguing. In 1990, American philosopher Judith Butler published Gender Trouble7 7 - Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 2nd ed. (New York and London: Routledge, 1999 [1990])., a work that puts forth a general performative theory of gender in which drag plays a central role. Since then voguing has had paradigmatic value: drag performances challenge the hyper-normativity of heterosexuality, which reduces gender to sexuality by means of a supposedly real and eternal concept of identity. Yet the drag parody shows us that this identity is always one of performance — it is a “continuous social performance.”8 8 - Ibid., 180. In this vein, voguing thereby becomes the stumbling block of this alienating process of reiteration. It allows “gender configurations [to proliferate] outside the restricting frames of masculinist domination and compulsory heterosexuality.”9 9 - Ibid.

As a triumphal expression of the phrase “fake it till you make it,” vogue shows that gender and social roles rely on persuasive mimicry: “If I dress like a businessman, walk like a businessman and talk like a businessman, then I can be a businessman,” a voguer notes in Paris Is Burning. Vogue balls are thus an affair of cosmetic transformation (the word cosmetic stems from the Greek term κοσμος or “cosmos,” which signifies “world” or “good order”): artists construct coherent identity-centred microcosms for themselves, small cells of mimicry strikingly framed. New subjectivities emerge and proliferate. Each ball is a competition, a challenge to all performers to faithfully interpret stereotypical roles stemming from approximately thirty categories, which include “the farmer,” “the school child,” “the diva,” “sex change,” “military” and “Marilyn Monroe.”10 10 - These categories have changed over time. Since 2000, voguers are particularly fond of the category “New way vogue with dramatics,” which is “very acrobatic and excessively masculine.” See Guy Trebay, “Legends of the Ball,” The Village Voice, January 11, 2000. They walk or dance while proudly exhibiting their greatest assets, be it their homemade costume, clean-shaven face, or refined silhouette. As Butler would say, such elements ironically frame those that are “falsely naturalized as a unity through the regulatory fiction of heterosexual coherence.”11 11 - Butler, 137. The game is deadly serious. The judges are strict and pay heed to every detail (voguers are immediately disqualified if it is discovered that their costumes were stolen), and competition is fierce. “Sometimes you feel as if you were in World War Three,” some young voguers have claimed. “Heterosexuals have declared war [on us], and we do battle at the ball.” Is vogue a kind of war that uses other means?

In the Waters of “La La Land”

Is vogue really a subversive practice? Does it succeed in undermining gender norms, or is it merely a process wherein such norms are idealized as they are grossly reiterated? Does the continuous creation of subjectivities really have an effect on social objectivity, or does it merely amount to the reification of the latter by absurd means? It bears mentioning that the fairy-tale character of nocturnal balls is like a “la la land” that contrasts sharply with the miserable life conditions of certain voguers.12 12 - This information comes from Irene Deros, a Montreal-based voguer who studied in New York. Interview with the author, December 10, 2012. Today, of course, the situation has improved in comparison to the early 1990s, when young people were often banished from their families after showing the first signs of homosexuality. The vogue “houses” in which such “children” were pampered and made ready for the balls more often than not became a voguer’s “real” family home.

In the best of cases, Butler argues that voguing questions “essentialized” identities. As such, its accomplishments are far from insignificant. Much like other drag practices, voguing reveals that the unity of the monolithic individual, the “self,” is an illusion, and that those who hold on to it are less trustworthy than those who take pleasure in unravelling it. Everyone performs in drag every day. Butler’s thesis recalls an idea put forth by Edgar Morin: “Each one of us is like a vast corridor. Strangers pass through it; we are not within ourselves. Rather, we are beyond ourselves, alienated by our dominant personality and made discontinuous by the various character-roles we play.”13 13 - Edgar Morin, Le vif du sujet (Paris: Seuil, 1969), 157 (Own translation). Our imagination, the anchor of our “mask-face, our vocal cords, our body,”14 14 - Ibid., 201. is the power that liberates us from our profound inadequacy of being. Embracing a multiplicity of egos, allowing one’s various “demons” to come forth, and mimicking the fantasies or hyper-normalized character-roles inside us is a healthy way to reinforce one’s metamorphic prowess (poiesis). Are not the rituals of possession a kind of “imitation” of the others that dwell within and that sometimes overpower us?15 15 - One can think here of the Hauka rituals (in Ghana) presented in the documentary The Mad Masters (Les Maîtres Fous, Jean Rouch, 1955). Are they not a means to conquer the role played by those who dispossess us of our very selves? Voguing is fierce when it unleashes the “whirlpool of spirits” that dwell in the “deep caverns” of the self, a whirlpool of spirits than can at last vogue openly. (M)imosa gives centre stage to individuals we have not yet dared to become.

[Translated from the French by Eduardo Ralickas]