Where Does It Hurt?

“Hesitant to speak of the therapeutic role of art or of sketching out the possibility of a catharsis, art history has featured multiple portrayals of pain without necessarily making it the object of an ethical engagement. Perhaps this is where contemporary art stakes its claim, by producing shapes and images of suffering that don’t forget the care, don’t ignore the trauma, and take the affects of the aesthetic relationship into account.”

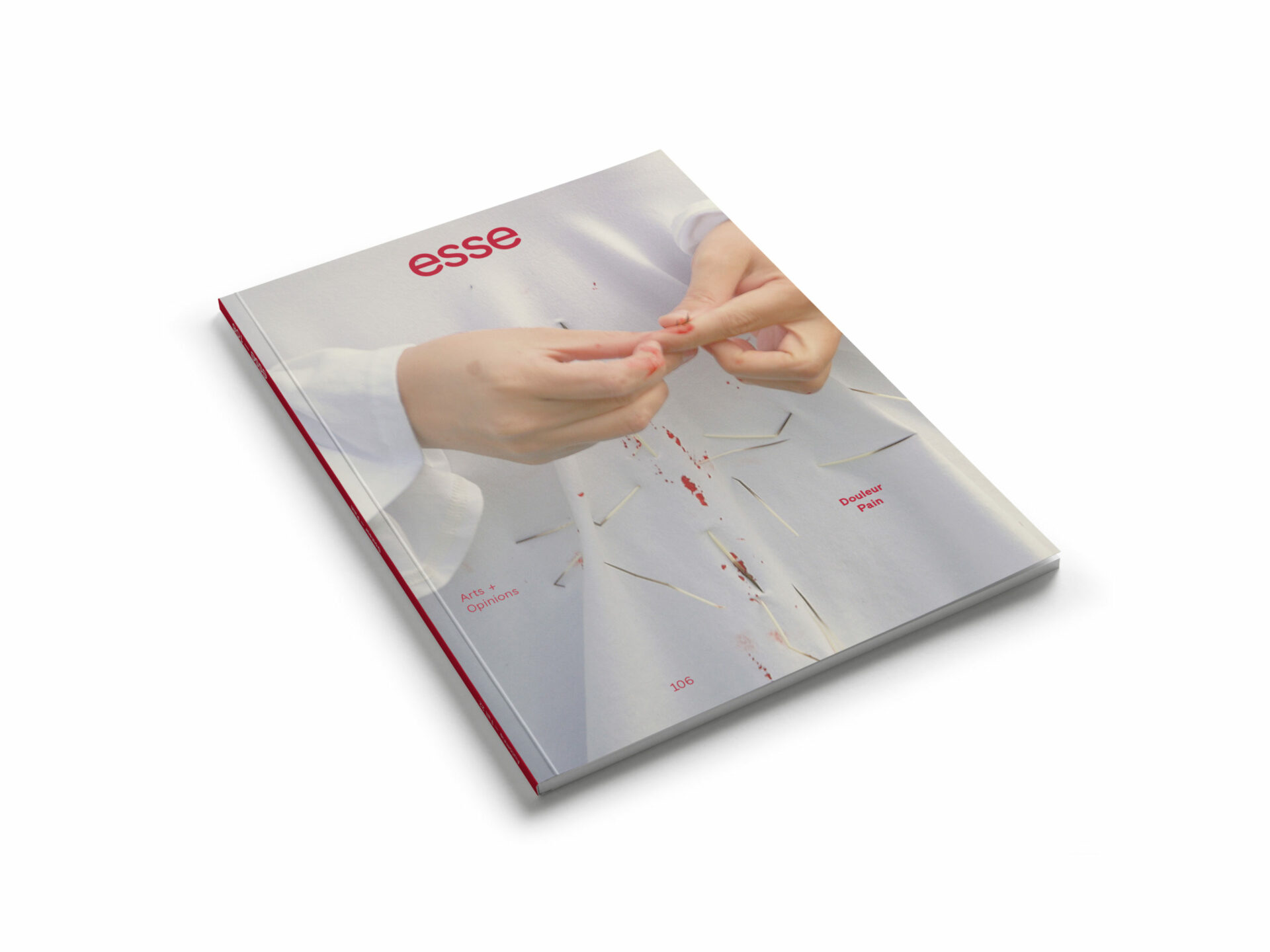

Life is full of pain that we have learned to deal with somehow or other. To speak about this pain, if the pain is not ours, is a delicate exercise that requires attention and empathy. Quoting the words of essayist Elaine Scarry, Martine Delvaux emphasizes in the first essay of this issue that while pain is a certainty for those who feel it, it brings up doubt for those hearing of another’s pain. This doubt is manifested in several ways, including being unable to recognize the other’s pain or refusing to validate it or even believe it exists. Although medicine has developed means of measuring pain, such as a pain scale, in situations of chronic pain or psychological trauma, disbelief and even suspicion persist. In part, it is this doubt that we are trying to dispel by carefully looking at pain that is a priori inexpressible and described in these pages as “silent,” “Subterranean,” or “intractable” and that transforms the body, as Joëlle Dubé points out, into a somatic archive.

This, however, does not mean objectifying pain through voyeuristic analysis. We amply understand Rouzbeh Shadpey as he points out that “the art exhibition is the doctor’s office when both are spaces of pain’s scrutiny, which is to say, pain’s unmaking.” Rather than placing pain under scrutiny, we intend to listen to it by giving voice to people who deal with physical and psychological pain on a daily basis in their bodies, their research, or their memories. We move forward in a universe that is more literary than visual; a universe where the “I” speaks; a universe where one attests as much to experienced pain as to observed pain. The personal narrative does not only serve a cathartic function; it is also a form of activism that advocates the need to consider all forms of suffering in medical, social, or political discourse, in which it is often hidden by ableism or to the benefit of the pharmaceutical industry. Against these attempts to eliminate pain — not in the sense of alleviating it but of making it invisible — more and more voices are speaking out. In these pages, therefore, we see an appeal to the sovereignty of bodies, especially the bodies of women, non-binary and racialized people, bodies united in refusing to be made invisible, certainly, but also in refusing to be stigmatized, including stigmatization that leads to the pathologization of plus-size people.

As sentience, namely the ability to feel pain, is obviously not limited to human beings, it seemed crucial to extend our thinking to the entire animal kingdom. The thorny subject of the pain we directly or indirectly inflict on animals for the purposes of consumption, research, or even artistic creation also demands our consideration. We have approached it from a philosophical perspective in relation to the ethical issue of speciesism and human superiority — which is perhaps one step towards the concrete ethical engagement suggested in the excerpt from our call for papers quoted in the epigraph. It is in this spirit and by valorizing an ethics of care that women groups from queer, trans, Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (QTBIPOC) communities have chosen a holistic method of individual and collective healing based on emancipation and on breaking the silence. Authors Manon Huberland and Maude Pilon associate the “desire for community” in suffering and healing to “the act of being together in this imposed wakefulness.”

* * *

I write these words with a Pink Floyd song in mind: “Come on now / I hear you’re feeling down / Well I can ease your pain… Can you show me where it hurts? … Just a little pinprick… That’ll keep you going through the show / Come on it’s time to go / There is no pain, you are receding… I have become comfortably numb.”

This feeling of becoming “comfortably numb” echoes the one we socially sink into when it comes to reacting to the pain and violence affecting the state of the world. Perhaps our “collective wakefulness” should consist in coming out of the anesthesia that blurs our gaze when faced with the suffering around us. This kind and vigilant wakefulness might help us to discover where it hurts and ultimately alleviate the pain.

Translated from the French by Oana Avasilichioaei