Democratic Art

Although the communist alternative might appeal to some, many artists, curators, and critics have rallied to the defence of democracy, either by seeking its redemption or by pressing for its ineffective liberal variant to give way to a form of direct democracy. Almost without exception, these efforts are laudable and indispensable. However, it is worth considering how cultural and intellectual production made in the name of democracy can sometimes embody values opposed to those that it is intended to promote.

The history of politicizing art is long and complex, but the most common contemporary formulation — let’s call it the critical paradigm — has its roots in Brecht’s theory of epic or “dialectical” theatre. By means of anti-naturalistic techniques, such as breaking the fourth wall, Brecht aimed to rouse spectators from their passive complacency with respect to the theatrical spectacle so that they might engage more critically with the dramatic material. Dialectical theatre was a political intervention to the extent that it sought to recalibrate people’s perceptions in a way that would disclose the hidden forces that supposedly governed their lives. As such, it was partly an exercise in pedagogy. Brecht argued that an alienating spectatorial experience would bring the spectator’s subjugated condition to conscious awareness, which in turn would provoke a political response.

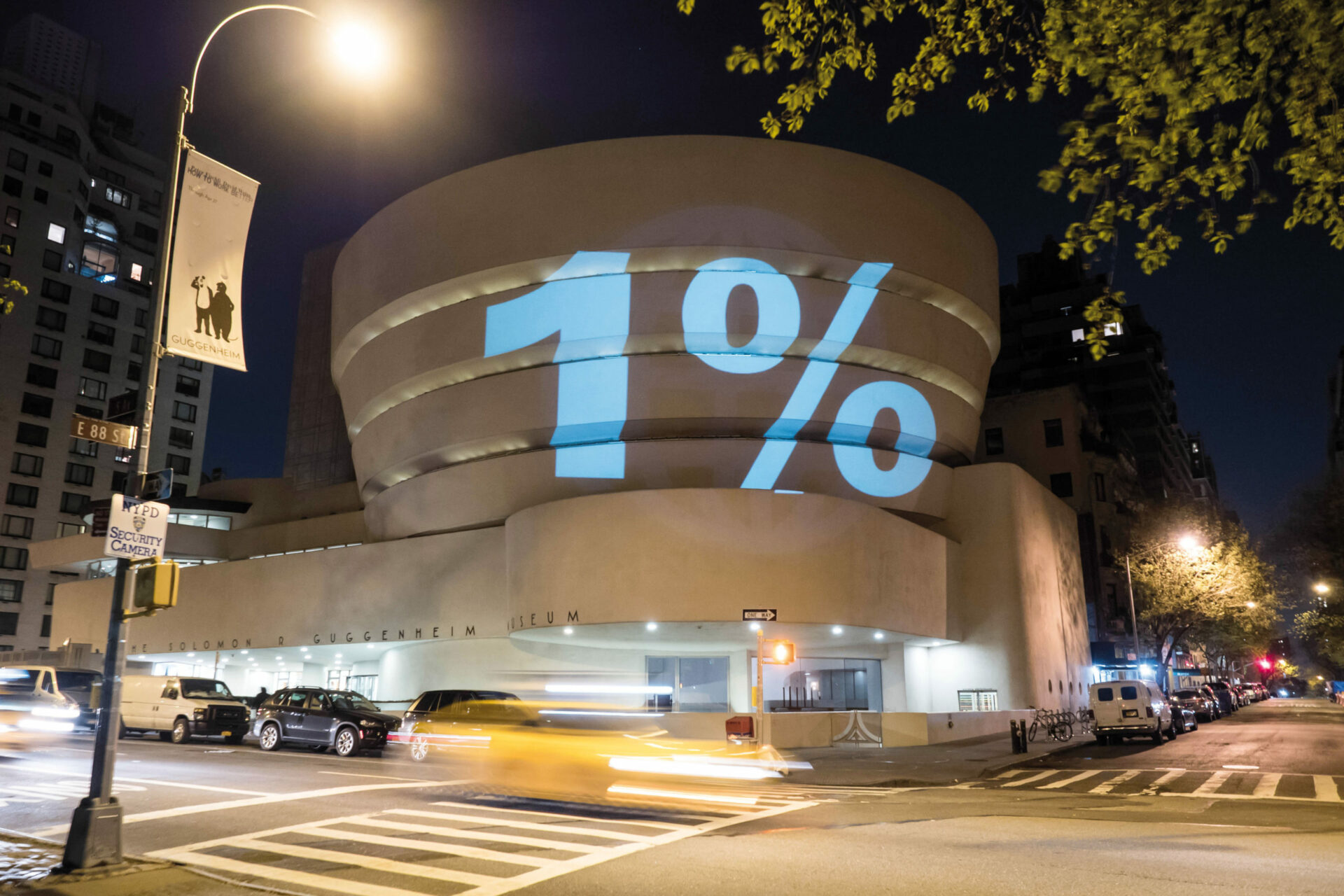

Project in April 2016, condemning the Guggenheim Foundation’s breaking off negotiations with the Gulf Labor Coalition about migrant worker’s rights at the museum’s Abu Dhabi location.

Photo: © The Illuminator

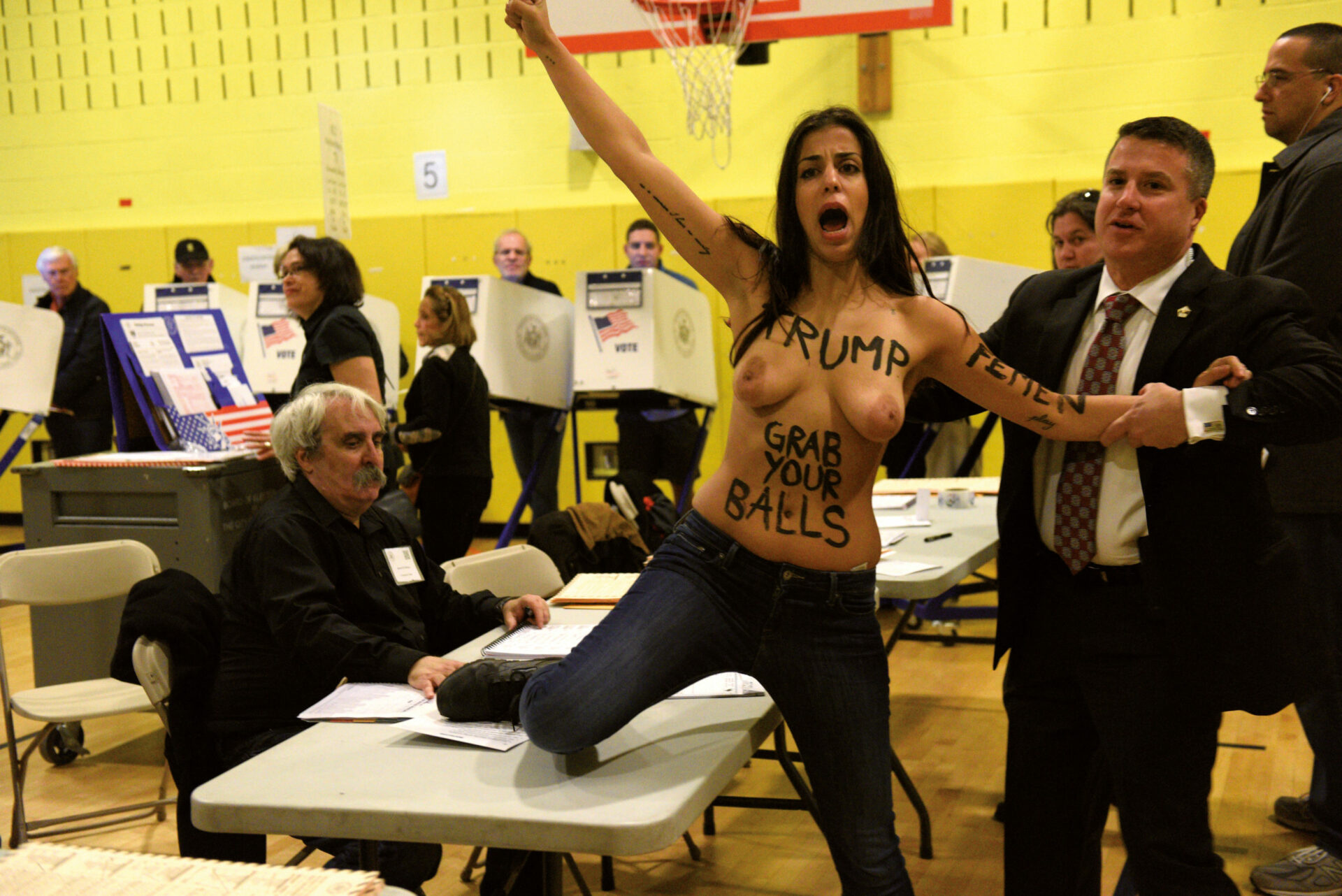

Much of today’s political art is heir to Brecht’s pedagogical program. We see this most clearly in projects that flourished in the wake of the Occupy movement. Not An Alternative, a twelve-year-old New York collective, is exemplary. It expressly positions itself at the “intersection of art, activism, and pedagogy” and aims to “affect popular understanding of events, symbols, institutions, and history.”1 1 - “About Not An Alternative,” Not An Alternative, http://notanalternative.org/about-us/. A pedagogical impulse also informs the activist art group The Illuminator. In its “call to arms” against social injustice, The Illuminator announces its mission to “shine a light on the urgent issues of our times.”2 2 - The Illuminator, “A Call to Arms from NYC’s Guerilla Superhero,” Blunderbuss Magazine (blog), May 19, 2016, <bit.ly/2j5vy7N>. Although this is clearly a figure of speech, the group also means it literally: The Illuminator’s main project consists of projecting pointed political messages onto the façades of public and corporate-branded structures. It achieved a measure of fame for what came to be known as the OWS Bat Signal: during the Occupy protests, it prominently defaced the Verizon building with a projection of “99 %.” As Yates McKee has noted, those who produce these and similar projects share an interest in “creative direct action,” a practice in which art is adapted to the logic of direct democracy.3 3 - Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (London and New York: Verso, 2016). See, in particular, the engaging and informative introduction. For McKee, such a project is sustained by what he calls the “post-Occupy condition,” or the widespread radicalization of cultural workers following the Occupy protests. One can’t help but draw parallels between the kind of political awakening McKee identifies — and that creative direct action is meant to propagate — and the raised consciousness that Brecht hoped to induce in the spectator by means of dialectical theatre.

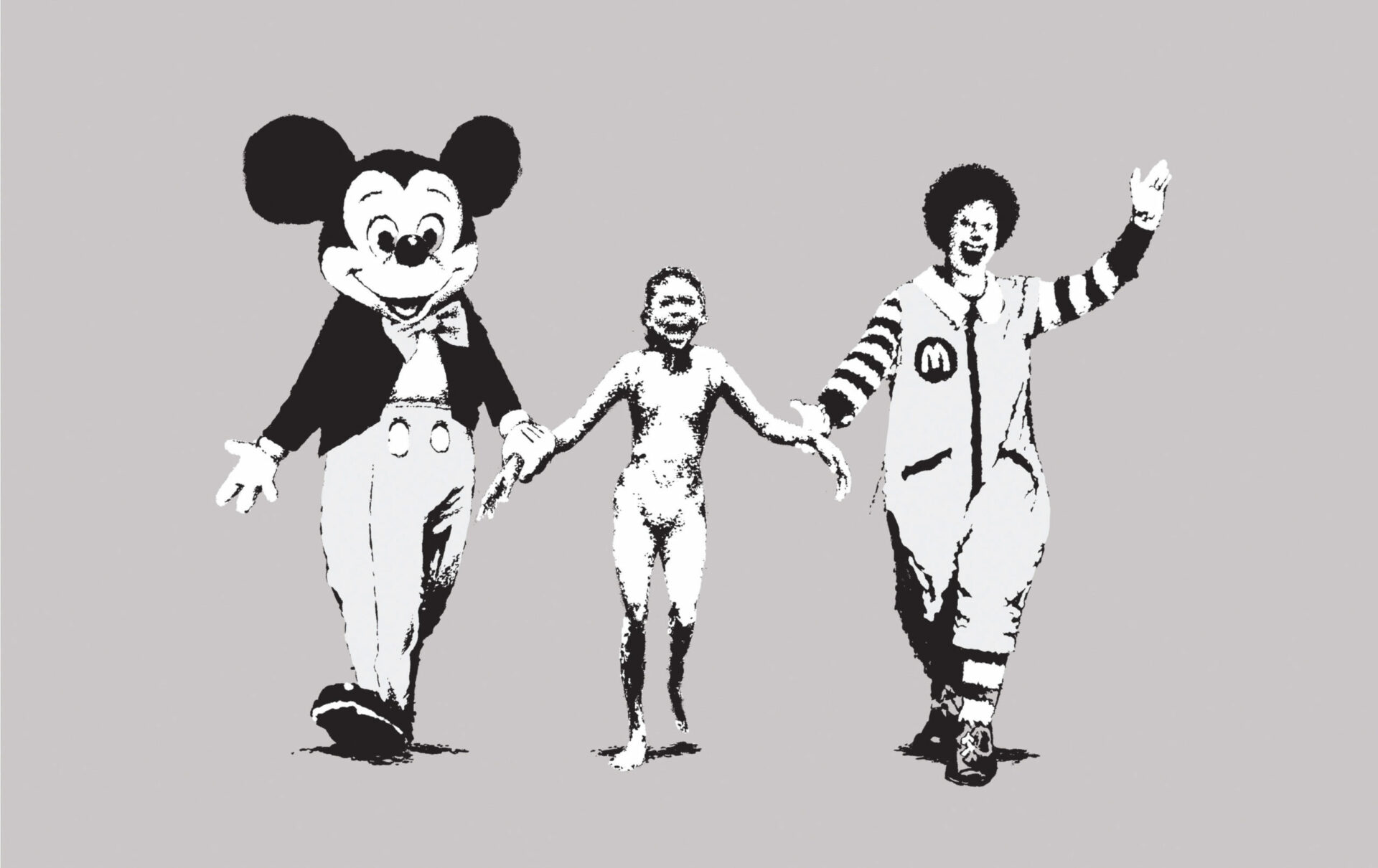

Napalm, 2004.

Photo: courtesy of Pest Control Office

Even when critical artworks do not make their pedagogical motives explicit, these motives are implied. A vivid example is Banksy’s Napalm (2004). By inserting a famous image of Phan Thi˙ Kim Phúc (also known as the “Napalm Girl”) between Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald, Banksy cleverly draws a moral equivalence among three kinds of imperialism — military, capitalist, and cultural. Recalling Brecht’s pedagogy, this jarring juxtaposition is meant to provoke a change in perception with respect to prevailing socio-economic conditions. The purpose of a raised consciousness, of course, is to serve as a political call to action. A similar logic informs relational aesthetics, which updates the idea of breaking the fourth wall in interesting ways. The classic example is Rirkrit Tiravanija’s pad thai (1990), a work that invites visitors to share a meal the artist has prepared rather than displaying an object of aesthetic interest to be appreciated at a spectatorial remove. Participatory art projects in general obey Brecht’s pedagogic principle. Carsten Höller’s Experience (2011) — the title constitutes more of a command than a description — and Maurizio Cattelan’s America (2016), which addresses the inequality ravaging the work’s namesake by providing participants with an opportunity to shit into a solid-gold, yet perfectly functional, toilet, are relevant examples. Not unlike dialectical theatre, they aim to deliver us from our supposed inattentiveness and apathy with respect to social conditions by inserting us into novel aesthetic contexts.

Dismaland, Weston Super Mare, 2015.

Photo: courtesy of Pest Control Office

There is much about critical art, so defined, to be admired and defended. But we should not indulge the fantasy that such art is wholly commensurate with democratic ideals. Although art can certainly modulate our perspective, remind us of the general nature of injustice by confronting us with specific cases, momentarily aestheticize our unthinking routines, and even help us rediscover the novel in the banal, it ceases to serve the interest of democracy once it purports to instruct us about the state of the world or otherwise guide our actions in accordance with its political imperatives. To the extent that it traffics in pedagogy, then, critical art is opposed to democracy.

This point is vividly demonstrated by Jacques Rancière, a philosopher whose entire career has been devoted to this very issue.4 4 - A useful summary of Rancière’s work can be found in Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, trans. Steve Corcoran (London and New York: Continuum, 2010), which contains a number of important essays. See also Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004), and “The Emancipated Spectator,” in The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2009), 1 — 17. In Rancière’s view, democracy is predicated on equality as an axiomatic principle. As such, it can be realized only in the absence of the pedagogical motive. Whereas democracy assumes equality from the outset and proceeds on the basis of that assumption, pedagogy reverses the procedure. It wishes to achieve equality but, paradoxically, it does so by first establishing a hierarchical relationship between two social subjects: teacher and student. Critical art succumbs to precisely the inegalitarian logic of pedagogy that Rancière identifies. The assumption that informs the critical paradigm is that the spectator is, to some degree or other, blind to his or her own subjugation. A certain ignorance on the part of the spectator is therefore assumed from the outset. The critical artwork wishes to reduce this ignorance as a means to achieve equality, but to do so it must resort to pedagogy: it assigns itself the role of teacher and confers on the spectator the status of student. Critical art, like all pedagogical projects, is therefore responsible for setting up the very inequality it promises to abolish.

Projection et rallye de danse dabkeh à l’évènement Stomp Out the Muslim Ban, Brooklyn Borough Hall, octobre 2017.

Photo: © The Illuminator

To the extent that we wish to prioritize the egalitarian ideals of democracy, critical art is ill suited for the task. Can we even speak of a democratic art, then? If there is such a thing, it comes down to qualifying equality as an axiomatic given. To better understand what Rancière means by axiomatic equality, consider the negative example of liberal or representative democracy — that mechanism of power by which we provisionally transfer our voice, if not our social identity, to those whose task it is to represent our interests on the national and international stages. The function of our representatives in Parliament, as it is in every representative democracy, is to speak on our behalf. What is brought to our attention with the increasing authoritarianism south of the border — and, indeed, in many parts of the world where representative democracy has succumbed to so–called populism and ethno-nationalism — is the flaw at the heart of this political philosophy: in the representative mode, there will always be those for whom nobody ever speaks and whose interests are never meaningfully represented on the political stage.

Rancière makes the point that the unrepresented suffer an exclusion that is as much phonic as social in that the grievances they express are registered not as signals to be read but as noise to be ignored. This is how politics is aesthetic: before a debate over policy can even be initiated, a determination must be made regarding whose speech is deemed worthy of consideration and whose speech is of no account, between the legitimate interlocutor and the inconsequential rabble. Rancière’s great insight is that aesthetics is a practice that not only configures sensory perception into intelligible and communicable forms but also, in the same gesture, parcels out and distributes spaces and forms of participation in a common world. It is by means of aesthetics that the social categories and attendant spaces that we inhabit — “woman – home” or “Black – ghetto” or “worker – factory” or “student – school” — are carved from the fabric of our sensible experience into the categories that constitute our social reality. Accordingly, statements made out of turn — by those who relinquish their assigned role and withdraw from their allotted space — no matter how humane and intelligent, take on the status of the unintelligible. The anti-democrat Plato, for example, was fond of dismissing the demos precisely on the grounds that they made no sense, that they were more inclined to grunt like animals than speak like humans, even though they used precisely the same language as the nobility. Today, Black professional athletes who refuse to stand for the U.S. national anthem are accused by conservative commentators not only of breaching established protocol (politics has no place in sports) but of merely “whining.”

For Rancière, axiomatic equality means taking the equality of all speaking beings as a fundamental premise. Social reality tends to obscure equality because it succumbs to a political imperative according to which legitimate speech must be differentiated from insignificant noise. But when social subjects speak out of turn, when they provide irrefutable evidence of the shared intelligence and humanity of all speaking beings, they assert an irreducible egalitarianism. They expose the hierarchies that structure the social order as purely contingent and show that other configurations of the sensible — alternatives to the social categories that organize our social reality — are possible.

Democratic art is simply art that puts this axiomatic egalitarianism into effect. Unlike critical art, democratic art does not tell the spectator what to do and how to think. Nor do democratic artists base their practice on the dogmas of official policy, for that would be antithetical to egalitarianism. Instead, art -serves the interest of equality most effectively by accepting its own insufficiencies and by refusing to anticipate its effects. If Brecht provides today’s critical art with a historical antecedent, then Marcel Duchamp might be said to serve the same purpose for democratic art. In this respect, the distance between Cattelan’s toilet and Duchamp’s urinal is more aesthetic than historical, despite Cattelan’s obvious attempt at homage. Duchamp’s readymade does not take social reality as a given and proceed to prescribe a way of thinking about it and a course of action to address its shortcomings. Instead, it throws some of the very categories that constitute social reality — art, artist, gallery, among others — into question. It suspends the rules according to which we assign roles and identify spaces. By the same token, it embodies an egalitarian principle that is strictly identical with democracy.

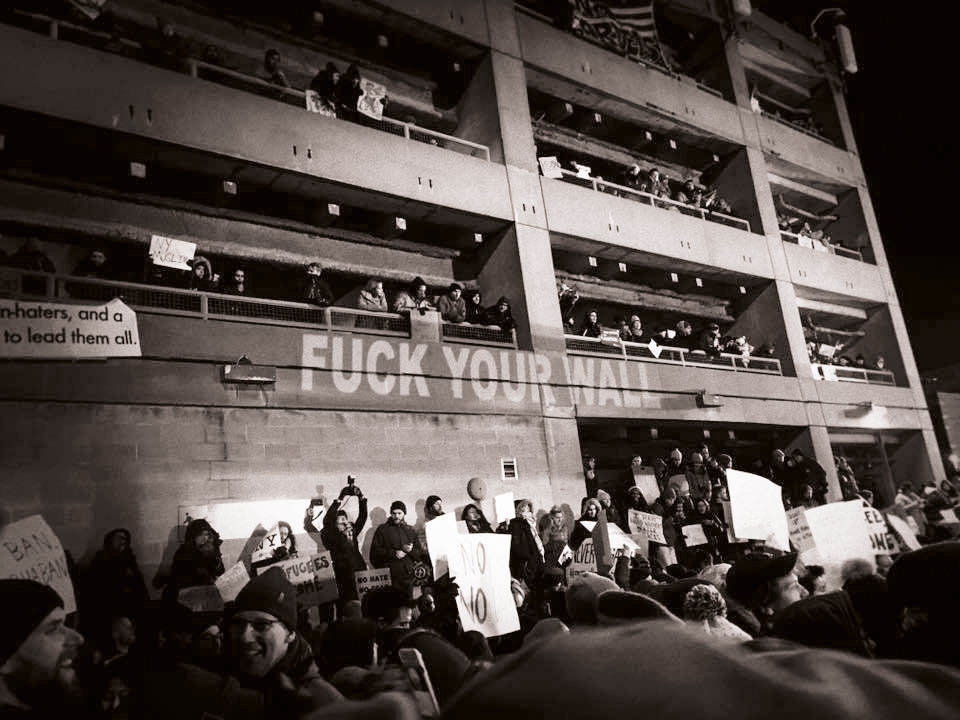

Des milliers de manifestants réclament la libération de voyageurs détenus à la suite de la signature par le président Trump du premier décret migratoire anti-musulman, aéroport JFK, New York, janvier 2017.

Photo: © The Illuminator

Aéroport JFK, New York, janvier 2017.

Photo: © The Illuminator

Balloon Debate, Palestine, 2005.

Photo: courtesy of Pest Control Office

For a contemporary example of democratic art we might look to another work by Banksy, one that deflects the pedagogical principle that structures Napalm and the more recent Dismaland (2015). Situated on the Palestinian side of the West Bank wall, Banksy’s 2005 stencilled image of a girl suspended above the ground by the upward lift of the balloons she is holding lends itself, on first inspection, to a pedagogical reading. But even if Banksy’s intention was to impart a message and advance a political agenda, the work finally abdicates any such responsibilities. It is insufficient and ineffective in Rancière’s sense because it refuses to make a claim over the spectator one way or another. In fact, the proximity of the work to such a politicized space is what makes its ultimate retreat from pedagogy so striking. We feel compelled to identify its lesson because of how it stands so precariously on the precipice of one. In the end, however, the work refers us not to a specific agenda but to a shared equality. If the work has a political attribute, then, it is a democratic one.