Photo: courtesy Galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal

The aptest statement on museology was given to us by art historian Hubert Damisch: l’amour m’expose.1 1 - Hubert Damisch, “L’amour m’expose,” Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, No. 29 (fall 1989): 81-90. [The phrase may be literally translated as either “love exposes” or “love exhibits” me, just as the French term exposition may refer either to the art exhibition or to the physical sense of exposure. – Trans.] That was in 1989. I have often cited the phrase and still find it as relevant as it is necessary, twenty years later. Those few words will always do better, for me, than any attempt at defining the curator’s elusive role, especially in these times of “Hollywoodization” in the visual arts. For the difficulty comes from the fact that this maker of art exhibitions, who was longtime a museum curator and a specialized art historian, has, since the opening of the exhibition market and the invention of the term independent curator in the 1970s, taken a plethora of faces. As such, the professional development of museological functions in the last forty years, particularly in Quebec, was paradoxically and simultaneously accompanied by the erosion of its specialized expertise, first and foremost that of the museum curator and the independent curator.

We see as much in several art museums, where “in-house curators” are in the process of becoming, as Yves Michaud put it, “professionals of the profession,” with interchangeable skills. Here and there, generalist curators emerge who, replacing the specialists (or putting aside their own speciality), can set themselves the task of coordinating exhibitions of any type or content, without necessarily producing knowledge that contributes to the advancement of the discipline — an expression that stands on shaky ground, unfortunately, when we speak of pure research. Unfairly, the institution will not put such a curator in charge of the most important or most appealing projects, frequently preferring instead to invite star curators, not necessarily for their expertise, but for a change in perspective and to draw the media’s attention, and hence the public’s. The contributions of the art critic and philosopher are familiar to us. At their best, their forays in the curatorial domain can generate thought or discourse capable of situating and enriching one’s encounter with the works in the exhibition. One may also think of the writer, movie-maker, or even the visual artist, called upon as curators in order to propose a personalized mise-en-scène or unique theme concerning the artworks and their time. But now many museums show little compunction about offering the role to personalities of the most varied competencies, preferably from outside the specialized discourse, as long as they are celebrities, inspiring, charismatic, impassioned, and of course so very touched by art!

Canada Pavilion, curator Louise Déry, Venice Biennale, 2007.

Photo: © Galerie de l’UQAM, 2007

Monuments, curator Louise Déry, Galerie de l’UQAM, Montréal, 2004.

Photo: Hugues Dugas © Dominique Blain

Photo: Louis-Philippe Côté

Meanwhile, the “love-exposed” curator develops his ideas, frequenting places where artistic activity engages reflection through ways of showing and telling that bear the signature of singular creativity, such as university galleries, artist-centres and, of course, certain art museums. Open to the movements of the time, sensitive to the artist’s work, and informed of his motivations, he acquires finely tuned insight into current forms in the visual arts without falling into a purely cerebral fervour. He is often alone, a solitude undisturbed by the extensive network of contacts that animates the scene of which he is part. If he feels alone, it is likely because he generally has the traits of the kind of intellectual we regretfully see passing into history, at a time when artists are treated like clown figures, and public entertainers are venerated. Our curator is also mistrusted, for he fails to hide his repugnance at seeing art reduced to an object of amusement or luxury, deprived of its reflexive potential. He deplores major museums’ hesitancy in supporting the riskier forms of current artistic production, while taking offence at the speed with which the same museums opportunistically endorse the work of artists suddenly placed in the limelight for reasons that have little to do with the development of artistic practice. There are indeed careers that develop at a faster pace than artistic practice, but one can’t begrudge them for it, since art, as Baudelaire observed, often thrives on misunderstandings.

Around this curator exposed by love, the art world is on the move! A lot is going on; the rejection of contemporary art has become a matter of people overwhelmed and disconnected; openings are packed, collectors become the subject of documentaries, giants of finance and business tailor their image through the acquisition of fetish works of art. The Pineaults, Saatchis, Ricards, Destes and Arnauds shop on all continents for their artworks, while debauching their curators — including some attached to major museums. Museum curators no longer have the capacity to impact the forces of art, to propose major exhibitions, and to bring insight, logistics, and financial resources to bear on building collections. One can understand those who defect, then, if motivated by the expression of a clear, though suspect vision. Indeed, a huge number of curators leave the museums to take either of two diametrically opposed paths: some choose the path of academia and (or) the way of hyperspecialization, certain that the university or the contemporary art or artist-centre can afford them the space needed to develop their discipline; others turn to the art market or to corporate collections, leading careers that have more to do with communications and promotional activity. As for the artwork’s reception, trendiness, the effects of celebrity, and the influence of a big name brand image often prevail over the appreciation of artistic content. The work of art is at once the object of attention and of estrangement: the attention given it is not necessarily concerned with its intrinsic nature, which has precisely the effect of keeping an understanding of its profound meaning at a distance, whether of itself or in the context of its exhibition and its enabling discourse.

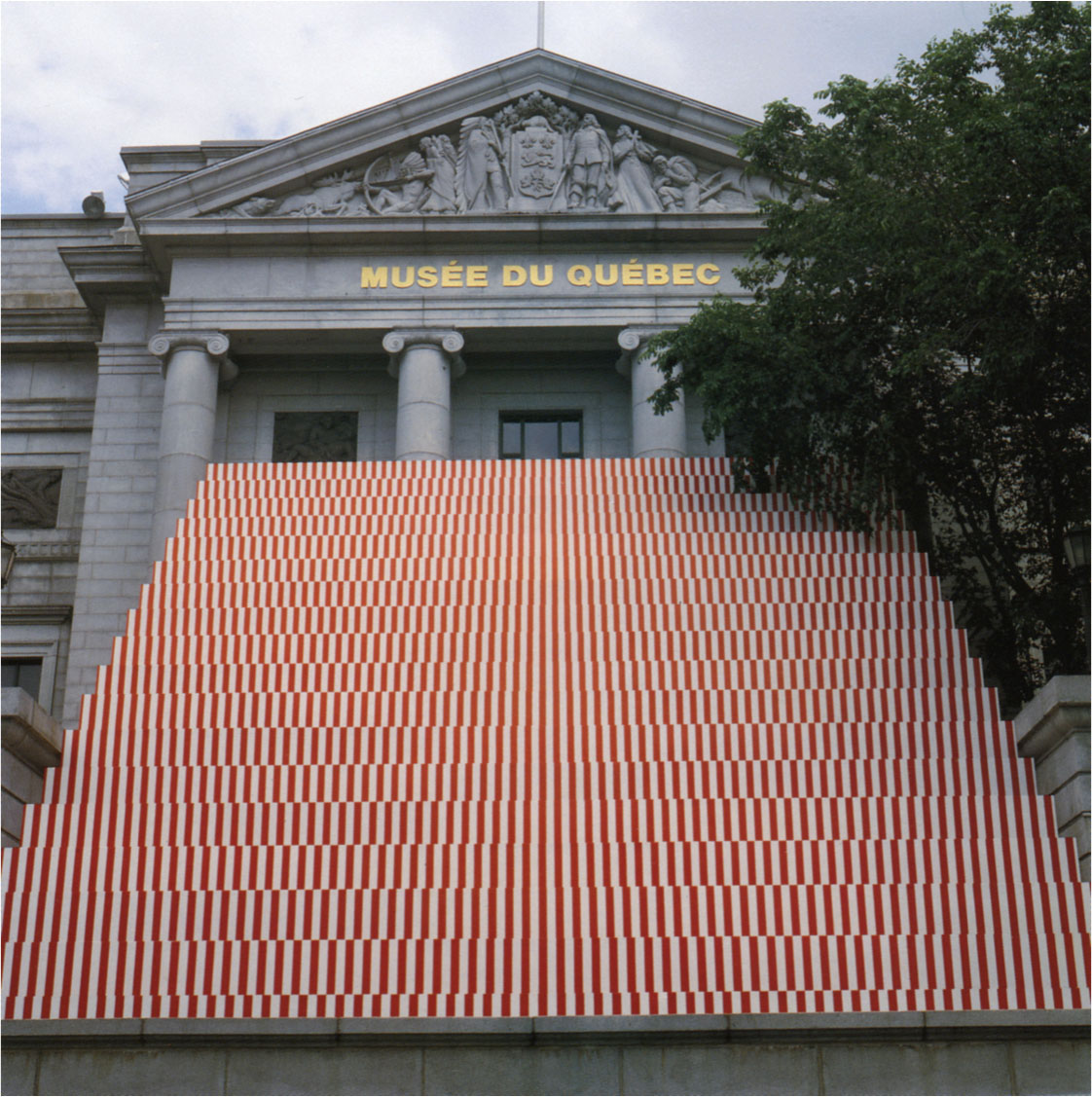

« L’escalier remonté » (1989), Territoires d’artistes. Paysages verticaux, curator Louise Déry,

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, 1989.

Photo: Patrick Altman © DB-ADAGP Paris, © Daniel Buren / SODRAC (2011)

Our curator exposed by love knows that the form of the exhibition is a text. He must present the works in close relation to the space of the exhibition, generating the idea of traversals, visual penetrations, reflections and references between the artwork and the space with its distinct architectural texture. An initial typology is thus developed, that of the gaze, which multiplies points of view, roundabouts and references, and then a second, that of the narrative, constituting itself like an intertext, with its own effects and byways, taking into account that works are sometimes given to us as utterance, sometimes as silence. In fact, the curator’s language is that of thought adhering to a body — the work — and their contact or encounter reveals this body to be alive and complex. Language serves to tell what is seen or looked at, but it is also envisaged — it takes on a face in a relationship to the body that enables the telling. To begin with, suggests Pascal Quignard, “we are brief books. Skin develops about two square metres of surface on us.”2 2 - Pascal Quignard, Les petits traités, Vol. II (Paris: Gallimard, 1990), 408. The exhibition’s envelope, its skin, is also charged with dense, compact meaning; it is the curator’s job to give it rich, meticulous articulation. Without which it is mere display, a presentation that has more to do with the effects of design than with the works. We have all seen very bad exhibitions that have nonetheless included very good pieces. Their skin was too thin, they had that detestable thinness of meaning. Add a little heavy-handedness to the presentation and failure is guaranteed!

The curator’s skin is on edge. For he is constantly wondering, in a land like ours where identity is largely defined by language,3 3 - Here, I am alluding to Quebec, where the French language, more threatened and therefore more protected than elsewhere, is a major issue of cultural expression and at the forefront of critical discourse. whether, contrary to literature, songwriting, theatre and the like, an essentially wordless art may truly reach and interest the media and the public. He witnesses, powerless, the gradual disappearance of media outlets even modestly devoted to the visual arts; he speculates on the depth of the sudden crisis in discourse, or on a transformation of the communications field; he suspects either an inability of the visual arts to adapt, or a discouraging invasion of ignorance among players in the media. His work hardly interests anyone outside the narrow circle of the visual arts. Notions of value seem to be denied, “personal taste” prevailing as the only and inescapable criteria, or non-criteria rather, discouraging any theoretical or critical requirement from the get-go. And yet, judgements concerning art proliferate in the media and elsewhere. If the medium is the message, one has to look at what happened to TV, newspapers, the radio. But what to do if the medium changes, if a new process arises that ushers in the reign of the cultural chronicler, the ultimate all-purpose journalist, even a golden age of the amateur commentator instantly shared by millions of subscribers on social networking sites? Who then will call the love-touched curator’s bluff? Who will peruse his exhibitions with the expected openness, time, curiosity, and respect? Who will take note of his “authored exhibitions,” of his competencies in the visual arts? Who will see this contribution as the expression of knowledge, and thus likely to matter in art history?

Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids), curator Louise Déry, 2002.

Photo: © Michael Snow, courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery,

New York & Galerie Martine Aboucaya, Paris

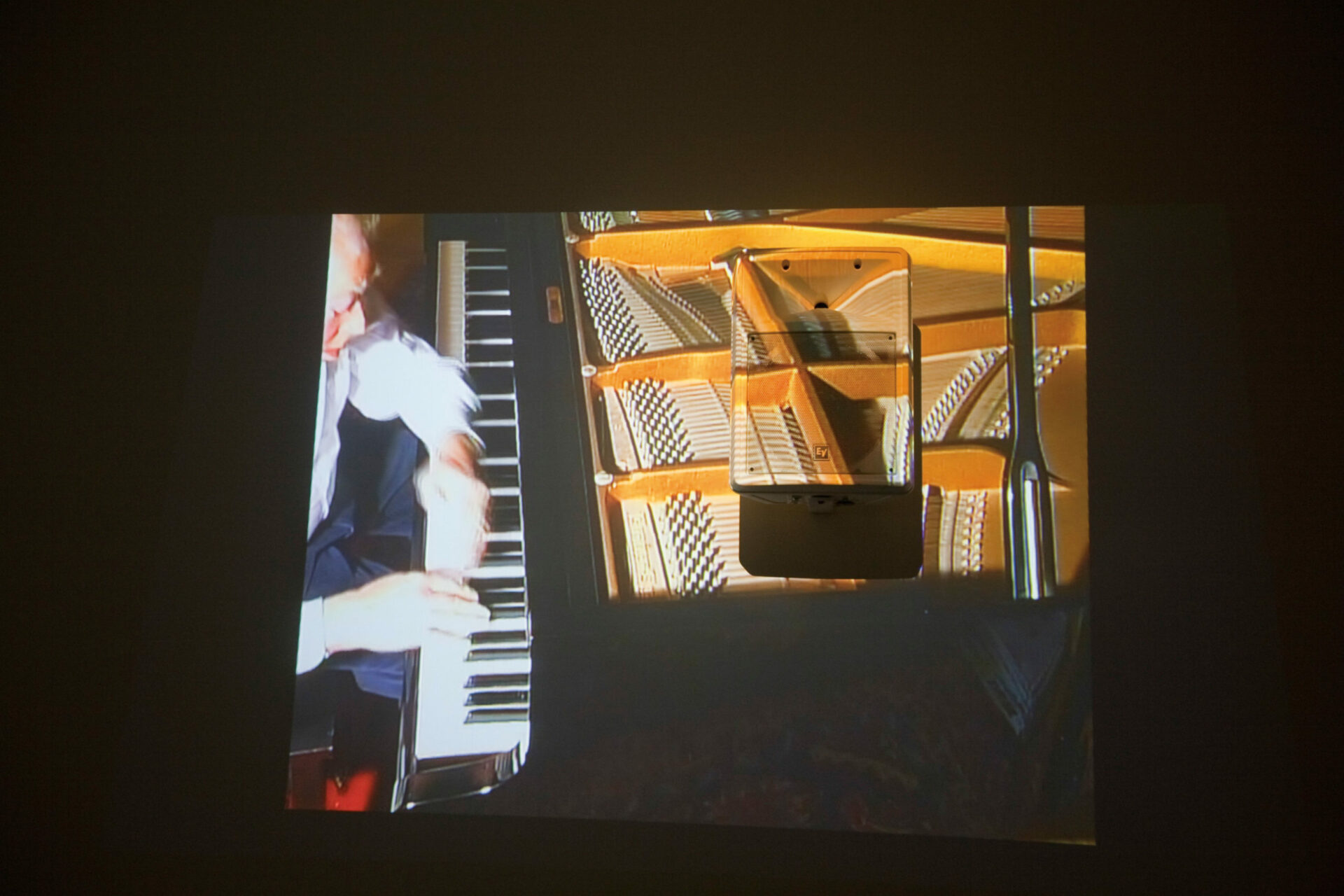

Piano Sculpture, curator Louise Déry, 2009.

Photos: © Michael Snow, courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery,

New York & Galerie Martine Aboucaya, Paris

History naturally teaches us that not all exhibitions produce knowledge and thought, that this requires a dual occurrence: the advent of both the work and the exhibition. The work of history consists in detecting the mechanisms that come into play in the exhibition and between the works, to record them and to situate their valid parameters in time. Though all museum and exhibition curators are involved in the spatial staging of the works (to widely varying degrees), they do not all bring the required awareness and competency to fully investigate the nature of the art work in the context of its exhibition. Jean-Marc Poinsot effectively located the notion of exhibited work as being closely connected with its conditions of utterance and exhibition, particularly in the adjustments made for its first showing. An art historian and theoretician of the exhibition, he urges us to take into account the “authorized narratives” of the exhibited work, so as to ensure its valid inscription in the space, in discourse, and in history.4 4 - Jean-Marc Poinsot, “Quand l’œuvre a lieu,” Parachute No. 46 (March-April-May, 1987): 76; reprinted in Jean-Marc Poinsot, Quand l’œuvre a lieu. L’art exposé et ses récits autorisés, (Geneva: MAMCO, and Villeurbanne: Institut d’art contemporain and Art édition, 1999). Because he insists on participating in the spatial setup, and because he has knowledge that is useful to the exhibition of the works, the curator exposed by love generates a large part of these narratives, with (or without) the artist. He acts on the basis of experimentation, freedom and, quite often, resistance.

Responding to resistance requires that we look at the object inside-out, that we refer the exhibition to itself, that we support a reflexive discourse that only the curator of love may bring forth: he who, before the white wall, is not struck with emptiness. Far from it. At some point, every time I hang or install a work, I am aware of those who have lingered in these spaces before me, who’ve touched this same space as me, this same wall, over the years; layers of paint can’t erase their presence. An exhibition never ends, really, and the takedown hardly diminishes the force of the imagination. The curator exposed by love is the sum of all the exhibitions he has produced, and at the same time the expert on a single work that will have really counted. Every moment I seek it out, the work of art revitalizes me. It is the question of origins that Pascal Quignard speaks of: “A missing image, an invisible, an unobservable, an off-camera, a margin, a blind spot, an out-of-sight makes the origin.”5 5 - Pascal Quignard, Sordidissimes (Paris: Grasset, 2005), 98.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]