photo : Martin Argyroglo

The growth of the cultural industry between 1980 and 2000 may have led one to think that curatorship in contemporary art had now become a sinecure. More museums, more art centres, and more events devoted to visual arts production: mathematically, this means more curated exhibitions. With visual arts production growing exponentially, it was a sure bet that the curator would generally become a pivotal and preeminent figure in the current art scene. To exhibit haphazardly, in bulk, with no structure to govern the artistic proposition, would be to risk taking this bulk offering as the very nature of living art. Such profuse and heterogeneous creativity requires a minimum of order, selection, thematic cataloguing. The all too predictable reign of the curator was upon us. It came. And its arrival did not disappoint. In the conception of exhibitions, the curator has become, and remains, a necessity.

Where’s the risk, then? In the possible “derailment” of the curatorial function. When the latter goes beyond the motions of art to create dubious genealogies and configurations in the name of ideas that are not primarily accountable to the reality of living art.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

& Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau, Paris

End of the Line

The 1950s and 1960s consecrated the model of the conceptual curator, in line with the nineteenth century and early twentieth. Pierre Restany, Harald Szeemann, and Germano Celant are its ultimate archetypes: a coterie of artists forms around and through them, bound by a common creative thread, a poetic and aesthetic sensibility, which they develop and refine intellectually.

The 1970s, the direct offshoot, created the partner curator. Often the director of a museum or influential exhibition centre, the partner curator was an energetic supporter of creative practices: Rudi Fuchs, Eddy de Wilde, Jan Hoet, Jean-Louis Froment… Theorizing isn’t the partner curator’s forte; most crucial for him or her is the special, supportive and fraternal relationship with the artist. The generation of “partner” curators preserves a substantial capital of goodwill among the creators who were their contemporaries, and for whom they fought tirelessly toward a respectable goal: to bring into the museum an often dissident creative production that had been excluded from the edifice of prestige and recognition.

In continuity, but also marking a break, the 1980s and 1990s ushered in a new type of curator that I’ll call the “Cultural Industry Curator.” The latter are defined as much by their competencies in art as by their communicative potential, and are becoming increasingly influential in the thriving cultural industry (with the proliferation of biennials and museums of contemporary art). A specialist of occasional artistic gatherings, this organizer uses artistic creation to his or her own ends. One of these outgrowths is the artist-curator, who proclaims him- or herself an “exhibition author” (auteur d’exposition) and comes into the world not so much as an art curator but as a super-artist developing a personal aesthetics by appropriating the work of instrumentalized artists (a criticism already made for the first time by Daniel Buren of Harald Szeemann in 1972, on the occasion of Documenta V).1 1 - Daniel Buren, Exposition d’une exposition (Kassel: Documenta V, 1972). Collins & Millazzo, doing the honours in New York at the end of the 1980s, were pioneers of the genre and garnered a following. Claiming a “vision” of art, the artist-curator relies on an established media network and presumes to prescribe. This twist will give rise to a generation of star curators — Victor Misiano, Rosa Martinez, Okwui Enwezor, Catherine David, Francesco Bonami, Daniel Birnbaum — who, overly solicited, quickly discredit themselves. The credit major exhibition organizers still give these super-curators is remarkable: Daniel Birnbaum, of Sweden and director of Portikus (Frankfurt), had, in the span of a few months, to assume the curatorship of the second Turin Triennial (winter 2008-2009) and the artistic direction of the 2010 Venice Biennale. Failure was predictable.

Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau, Paris, 2009.

photos : Martin Argyroglo

Of Royal Prerogative and Resistance

A sad development? Yes, if one considers, in some now famous cases, that “curating” may become an artistic genre in its own right. At the 2005 edition of the Biennale de Lyon, each artist whose work was exhibited had to be represented — chaperoned — by a curator, all under the stewardship of two curators-in-chief, Stéphanie Moisdon and Hans Ulrich Obrist. The outcome was laughable: there were more curators in the exhibition than artists. And what can be said of the last edition of Manifesta, in Murcia and Albacete (fall 2010), where a copious curatorial board imposed a meticulous work plan on the guest artists before the exhibition? After selecting the artists, the curators set out to conceive a project together. Each work “cell” (such as the ACAF [Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum (Egypt-US)], or tranzit.org [Austria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia]) proposed a thematic framework to each of the artists, with specific productions in mind. Thus, transit.org summoned the artists to conceive a temporary group museum, born from reflections on what an exhibition might be today, following a fixed set of rules laid out in a Constitution for Temporary Display. Among other programming imperatives, the ACAF urged the artists to adopt a parliamentary form of discussion to develop their point of view on art and the exhibition. Enough is enough! Artists enrolled in this curatorial quagmire are hard pressed to develop a personal project.

This type of excess is no minor thing; though it may have become so commonplace at the turn of the 2010s that we now consider it legitimate — the principle of giving carte blanche to some curator or other. What do artists think of it? To question or protest is to condemn oneself to exclusion. But every constituted society, concerned with a counter power, produces its fringe elements, and every reality in crisis induces its reappropriation by autonomous individuals taking corrective action. Alternative curatorial initiatives began developing in the 1980s, with a number of exhibitions mounted in non-institutional spaces, including artist-run centres devoted to highlighting non-western or minority cultures (political or sexual). The field of art was broadened, be it along dissident paths. Many exhibitions organized in the 2000s were devoted to big world-worrying questions rather than to those centred on the self. One thinks of group shows in recent years dealing with art in relationship to homosexuality (In a Different Light or The Eighth Square, in San Francisco and Cologne), with contemporary psychological disturbances (Niet Normaal, Amsterdam), or with ecology (Moral Imagination, Museum Moisbroch, Leverkusen): a wholesale return to the thematic proposition, which targets an issue, against the personal proposition, which drowns it in favour of curatorial attitude.

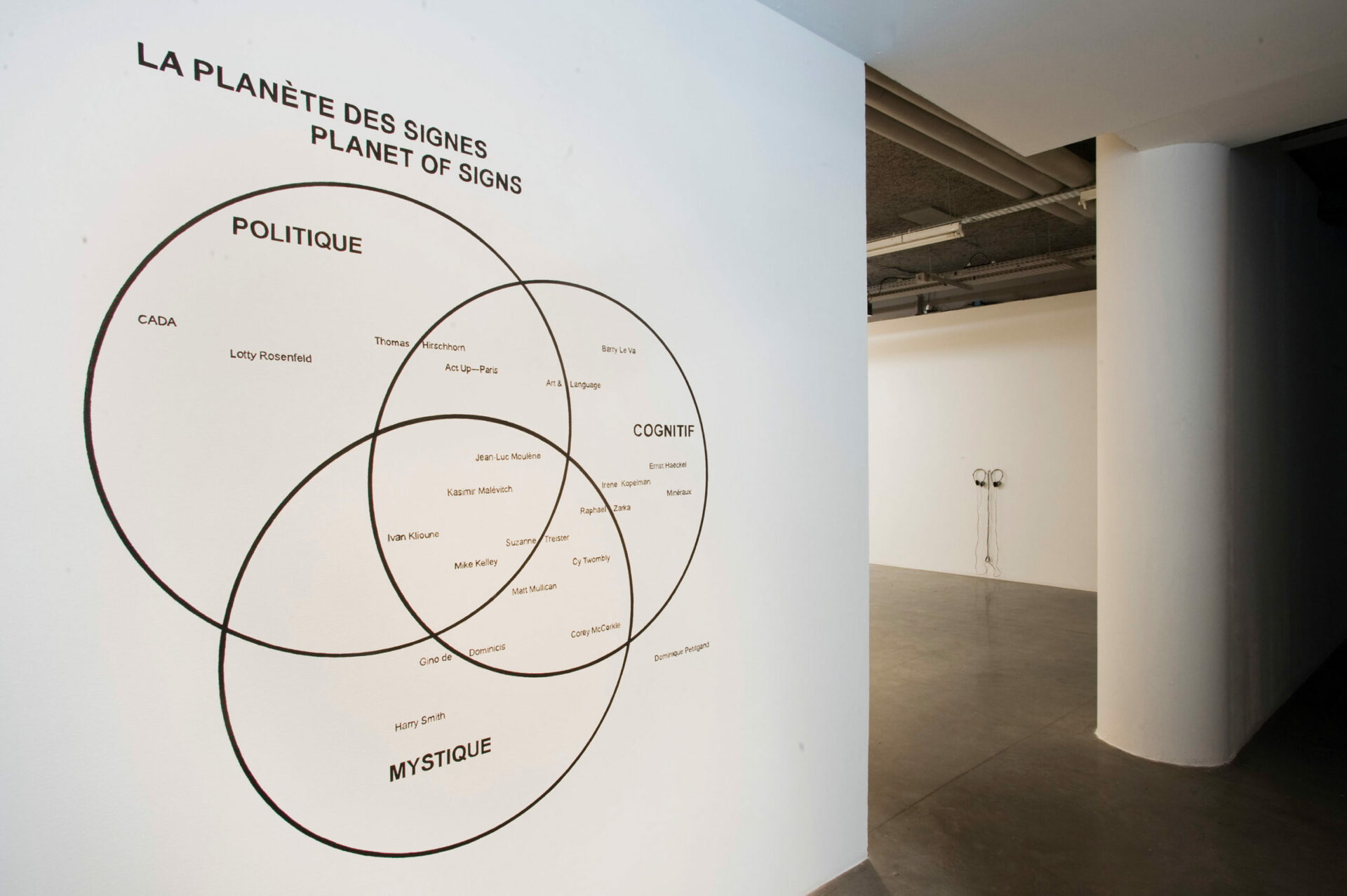

Alongside curatorial stardom, there are lots of curators much less suspect of personal ambition — the ever-essential “ants.” Their first rule is to serve the artist; OF THE ART ON DISPLAY, ONLY EXHIBIT WHAT ONE FULLY UNDERSTANDS, AND FOLLOW A PROCESS BY WHICH THE ARTIST COMES FIRST.2 2 - On the “ant” curators, see “Mes idoles sont les fourmis,” interview with Paul Ardenne, 2010, http://sophielapalu.blogspot.com/2010/02/mes-idoles-sont-les-fourmis.html. Guillaume Désanges, over a two-year period, and at the same site, devotes four consecutive exhibitions to the question of the relationships between art and signage (La Planète des Signes, 2009-11).3 3 - La Planète des signes, Le Plateau-FRAC Île-de-France, Paris, 2009-2011. Another “honourable” form of curatorial action is evinced by Évelyne Jouanno’s unique creation (at first with artist Jota Castro), the Biennale de l’Urgence, in 2005. The intent of this “Emergency Biennale” is to bring as many artists together as possible for the plight of Chechnya, then being crushed by Russia. How do you exhibit in Grozny? Jouanno gets the highly practical idea of the suitcase, then persuades a number of artists to create transportable works. In five years, the suitcase will have gone around the world.

Mark Wallinger: The Russian Linesman, 2009.

photo : permission | courtesy Hayward Gallery, London, UK

Mark Wallinger: The Russian Linesman, 2009.

photo : permission | courtesy

Hayward Gallery, London, UK

« Smugglerius (Ecorche of Man in the Pose

of the ‘Dying Gaul’) » (1834),

Mark Wallinger: The Russian Linesman, 2009.

photo : permission | courtesy

Hayward Gallery, London, UK

The Artist Curator

One of the art institution’s responses to the crisis in curatorship consists in asking artists, and not official curators, to conceive exhibitions. An artist’s exhibition has no use for themes or issues, but delivers instead a cerebral and embodied image of art, the materialized form of an intimate narrative where the selection of works of art replaces words. A selection conceived by an artist need not be didactic or subject to an academic cause or “trend.” It need only testify to an inner landscape, a poetic perspective, or to engage the spectator in a particular exchange.

While the idea of an artist’s exhibition isn’t new, it becomes institutionalized at the turn of the millennium. Such is the case with Britain’s Turner Prize. The consecrated winner is invited to curate an exhibition. Thus, Mark Wallinger, winner of the 2008 Turner Prize, gave his exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, a strangely resonant title: The Russian Linesman: Frontiers, Borders and Thresholds.4 4 - Mark Wallinger Curates: The Russian Linesman. Frontiers, Borders and Thresholds, The Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, London, February 18 – May 4, 2009. Explanation? At the 1966 Soccer World Cup, where England faced Germany, a disputed goal was given to the British by Azerbaijani linesman Tofik Bakhramov, thus depriving the Germans of ultimate victory. Asked years later about the decision, Bakhramov had apparently answered: “Stalingrad.” A way for this referee to exact revenge on the descendants of the Wehrmacht soldiers who had led a bloody escapade in Stalingrad, where a million people perished.

How does this reference concern contemporary art, to the point of making an exhibition of it? The reason, essentially, is of an aesthetic nature: Wallinger’s exhibition revolves around the issue of false or manipulated perception. Art is the field of simulacra par excellence, of the false given for true, of the dead for the living, of there for here, in a play of transmutations the validity of which demands that the spectator must let him- or herself be persuaded. Each of the works in Wallinger’s exhibition presents itself as reversible, accentuating uncertainty, that engine of curiosity. Though he may not be innovating on an intellectual level, Wallinger defines so particular a way of adumbrating an issue that it upsets the established code: the artist’s heterogeneous structures are presented together, in accordance with a logic that cannot be called into question.

The artist as Master Mind, against Reason if need be.

Translation, Palais de Tokyo, 2005.

photo : [email protected]

Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2005.

photo : permission | courtesy Evelyne Jouanno

Foundering Still

The practice of handing over curatorship of an exhibition to an artist is appreciated at this time, it’s in the Zeitgeist of the 2000s, as evinced with the showings of Ugo Rondinone (2007), Jeremy Deller (2008), and Adam McEwen (2010) at the Palais de Tokyo, or Jan Fabre at the Louvre, among others. From the institution’s point of view, it’s a good deal: as such, the exhibition content is validated quality-wise. That said, how would an artist’s perspective, the expression of his or her poetico-aesthetic culture, be a priori more interesting than that of anyone off the street? Would not the logical conclusion of “carte blanche” be precisely to stop anyone on the street and ask them: “What exhibition would you like to mount?” In reality, the art institution would never confuse the artist with the stranger, were they even to share the same world and have the same point of view about it. Despite appearances, the art system fully intends to operate with its own actors first. Though a great collector may be allowed to propose “his” or “her” exhibition — incidentally, most often an imposture, as major collectors generally entrust their collection to paid consultants (curators?) — they won’t go so far as to ask just anybody to conceive and present whatever they like.

In the most generous of cases, they’ll call on collateral members of the system, as was done, for the worse, by the Palais de Tokyo in the summer of 2005 for the exhibition Translation, given to their catalogue graphic designers, Michael Amzalag and Mathias Augustyniak, of M&M Paris. For the worse? M&M Paris leached some twenty works from the collection of the wealthy Greek real estate agent and major contemporary art collector, Dakis Joannou: works by Jeff Koons, Gabriel Orozco, Ashley Bickerton, Mike Kelley, Cady Noland, Vanessa Beecroft, and Shirin Neshat. And then? The designers used the entire exhibition space as a medium free to be “designed,” playing with the masterpieces entrusted to their care, liberally multiplying interlocked perspectives, collapsed views, inserts and other spellbinding effects. The Palais de Tokyo may be said to have been transformed into an immense radical chic apartment. What would the artists have thought, whose works were sacrificed on the altar of plastic raving?

M/M (Paris), « Figures [Pi] » (2005 ), « Moquette [Etienne-Marcel] » (2002);

Liza Lou, « Super Sister » (1999) &

M/M (Paris), « The Alphabet [Supersister] »

(2001-2005) Translation, Palais de Tokyo, 2005.

photo : [email protected]

Mike Kelley, « Brown Star » (1991),

Translation, Palais de Tokyo, 2005.

photos : [email protected]

Curator Beware!

The favour given to artist-curated exhibitions is no coincidence. For the art institution, they afford energizing new blood at a time when its conventional offerings are often seen for what they are: filler. Who’s to complain of creating and opening so many more exhibition venues? You do have to fill them though! Currently, frenzy risks taking hold in the institutional contemporary art system. Every new season has to deliver its trendy exhibition; every big local event, no matter how mercantile, its crystallization of high artistic moments and cultural urbanity. A tiresome comedy, painful to watch, and falsely dynamic, on a beat having nothing to do with art’s true rhythm, which breathes with the artist’s personal evolution, aloof even from the motion of the world.

What then? The perfect exhibition, let it be said, will never exist, whether it be monographic, collective, thematic, or personal. The flaw is fundamental. The curator should, therefore, envisage the exhibition as a perfectible thing, and not as a “finished” event-defining production. For contemporary art, the exhibition will never be an exact barometer, and the curator’s craft, never an exact science.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]