Photo: courtesy of the artists

Art Labor: Communal Land Protection in the Face of Industrial Extraction

As a result of those profound transformations, the Jarai people have been front-row observers of the damage caused by coffee, rice, and rubber farming in the region. Operating within a creative framework, Art Labor examines the influence that colonization and globalization have exerted on the current agricultural landscape. Its projects thus function as a space for rumination on the future of agrarian communities, steering toward a renewed communal relationship between the land and its inhabitants.

According to Jarai cosmology, the dead go through a series of reincarnations before ultimately reaching a new existential form. During the final stage, they are transformed into evaporating dew, an intermediary state between water and air. This marks a state of non-being, and thus the beginning of a new life cycle. Jrai Dew (2016 – ongoing) transposes the themes of death and reincarnation through a garden of wood sculptures. The display mirrors a funeral tradition preserved in the Jarai community wherein the dead are buried in the forest, where life both begins and concludes. The sculptures, each carved by a skilled Jarai artist, go through various stages of decay due to being exhibited outdoors in all kinds of weather. Depicting anthropomorphic entities or creatures drawn from local folktales, they bear witness to a craft that has remained through centuries. Yet, they are also products of an intricate origin: each sculpture is made from discarded tree trunks found on coffee, peppercorn, and rubber plantations — the very trees that, for many people in the region, evoke narratives of displacement due to relentless land extraction.

Jrai Dew, 2016-ongoing, installation views, Blut Grieng, 2016.

Photos: courtesy of the artists

One might ponder how recycling tree trunks can serve as a balm for the harm caused by uprooting. Although responses to this question may vary, Truong Công Tùng’s work offers an optimistic vision. Long Long Legacies (2021 – ongoing), an artwork made from similarly discarded wood sources, unfolds as a gigantic beaded curtain. Its woven pattern serves as a healing of what has been torn apart, metaphorically transcending the fragmentation of land caused by rapid industrialization. The entanglement of wooden beads also evokes a yearning for a revitalized communality in the Central Highlands, something that Tùng deems essential for the sustainable development of the region’s agricultural sector. Embracing a different set of configurations, a similar sense of hope permeates the Jrai Dew funeral garden, which symbolizes the death of things but also entails the emergence of a new dawn.

Long Long Legacies, 2021-ongoing, installation view, 2021.

Photo: courtesy of the artist

In addition to the wood sculptures in Jrai Dew, traditional Vietnamese cuisine and beverages have also assumed a predominant role in each iteration of the project. During each opening, the Art Labor collective brings forth a gathering of local foods and refreshments that have been significant in the transmission of intergenerational recipes and knowledge. Visitors are offered ruou cân, a fermented rice wine harvested from the mountainous forests of the Central Highlands. Typically drunk by multiple individuals at once, each holding their own straw, the beverage creates a flux of proximity that holds the promise of meaningful conversations among community members.

Jrai Dew, 2016-ongoing, performance view, Blut Grieng, 2016.

Photo: courtesy of the artists

The collective’s interest in food sharing aligns with a form of mediation already well anchored in contemporary art. An earlier example of this can be found in Rirkrit Tiravanija’s 1992 exhibition Untitled (Free), for which he served Pad Thai to gallery visitors as his primary — and sole — artwork. Although Tiravanija’s gesture was part of a broader conversation around relational aesthetics, there remains a fitting connection to Art Labor’s methodology. For Tiravanija, the act of partaking in a communal meal served as a means of engaging with and understanding the other in a sustained and authentic manner. For the collective, the same act supports their aspiration to build bridges among the various ethnic groups working on the Central Highlands farmlands. To a greater extent, this desire for communality also applies to the complex relationship between Jarai farmers and private corporations competing over the same agricultural territories.

In a utopian vision in which these two parties would find themselves sharing a glass of ruou cân from the same vessel, one might ponder whether such a gesture could suffice to prompt a re-evaluation of their shared responsibilities toward the land, the food, and one another.

Although many of Art Labor’s initiatives radiate optimism, its single-channel film Drowning Dew (2017) embodies a different tone. Divided into six parts (Bone, Death, Crow, Coal, Grasshopper, and Dew), the film is a visual chronicle of the rapid socio-cultural and environmental shifts taking place in the Central Highlands amidst its uninterrupted industrial development. Through poetic imagery, the film braids these transformations into narration by intertwining them with various Jarai myths. Oftentimes under-published, neither translated nor well collected, Jarai myths are prone to falling into oblivion even though the metaphors they encapsulate remain as pertinent today as they were centuries ago. Addressing the erasure of such historical fiction, the Vietnam-based curator Zoe Butt asks, “How are our imaginations of a different present informed if our myths are denied reinterpretation and our archives non-existent?”2 2 - Zoe Butt, curatorial essay for Thao Nguyen Phan’s exhibition catalogue Poetic Amnesia (Ho Chi Minh City: The Factory Contemporary Art Centre, 2017).

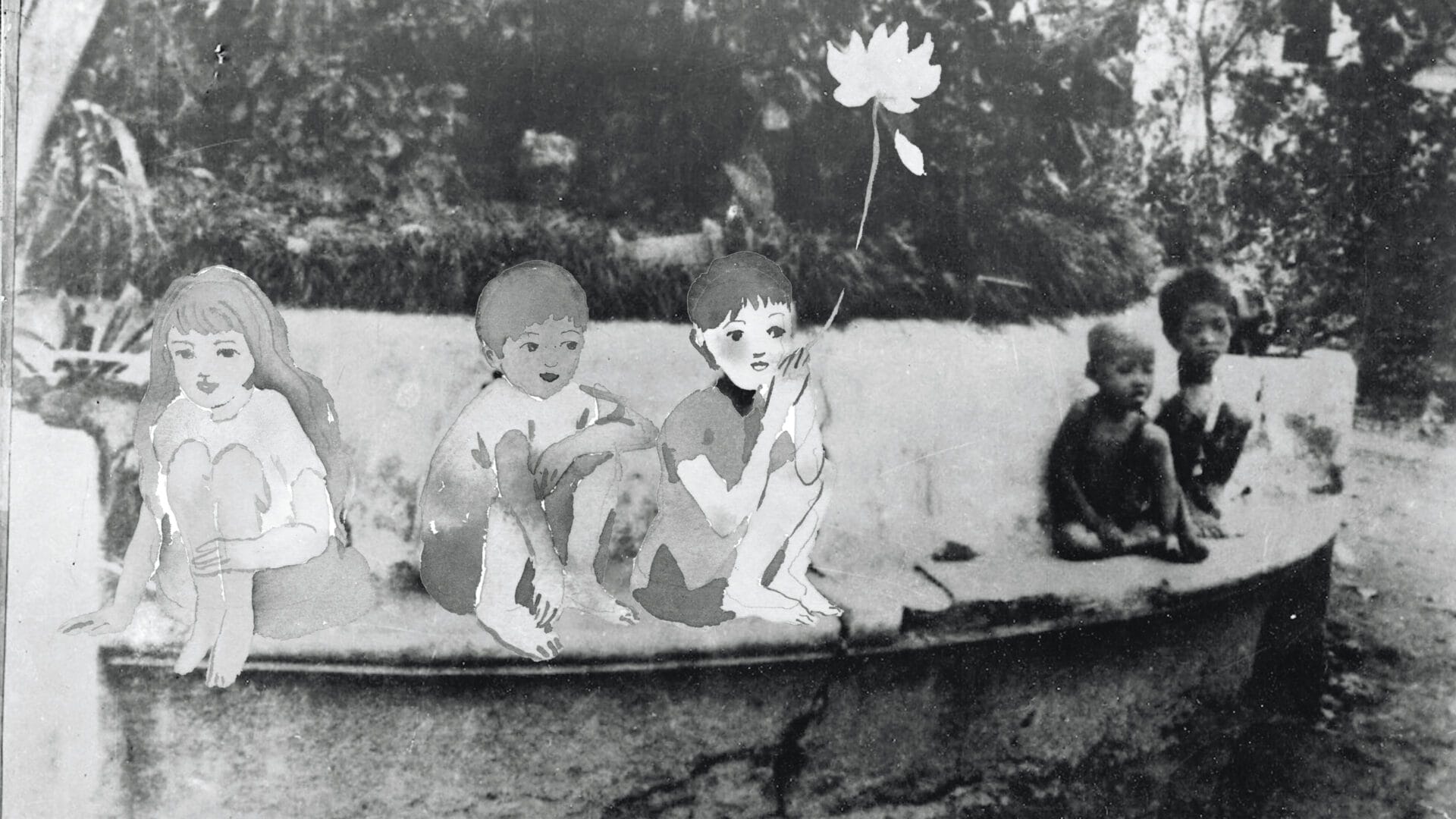

Once again, the collective refrains from delivering concrete answers. Instead, the independent work of its member Thao Nguyên Phan expands this inquiry. Through her multi-channel video installation Mute Grain (2019 –ongoing), Phan weaves a fictional narrative centred on March, an adolescent turned into a hungry ghost during the little-known 1945 famine in Vietnam. This historical event unfolded as a backlash to the Japanese occupation of French Indochina during which the Japanese administration coined the mantra “Uproot rice, grow jute,” emblematic of the wartime exigencies forced upon local farmers. This directive led to a decline in rice cultivation and, ultimately, to the famine’s tragic toll. Drawing inspiration from Vietnamese folktales and oral traditions, Phan mounts a compelling case that resonates with the enduring famines of this day and age. Most importantly, her work sheds light on the significance of food security and its inextricable link to the colonial legacies that have shaped agricultural landscapes.

Mute Grain, 2019, video stills, 2019.

Photos: courtesy of the artist & Galerie Zink Waldkirchen, Seubersdorf

Mute Grain, 2019, installation view, Wiels, Brussels, 2020.

Photo: courtesy of the artist & Galerie Zink Waldkirchen, Seubersdorf

The Đôi Mói reforms were introduced in response to extensive flaws observed in Vietnam’s planned economy — a model it had borrowed from the Soviet Union. The reforms were aimed at revitalizing the country’s economy, and the agricultural sector came to be seen as key to potential prosperity. In pursuit of this goal, the Central Highlands were designated as a profitable territory for coffee plantations, which swiftly led to the mass commodification and commercialization of coffee in the region. With the growing demand for Robusta coffee beans from within and outside Vietnam, the proliferation of coffee plantations came at the steep cost of massive deforestation. Lands that historically belonged to Indigenous farmers are now being exploited by private corporations. Hoping to champion more sustainable agricultural practices, in 2016 Art Labor introduced a nomadic Hammock Café that it has taken with it during its exhibitions abroad, offering a space for gathering and unwinding. Visitors also get to enjoy a rotating selection of films by Southeast Asian artists, including Jun Yang, Davy Chou, and Taiki Sakpisit. Yet, beneath the vibrant facade of this space stand the vestiges of French colonialism in Vietnam; although coffee has become an integral facet of Vietnamese culinary culture, it was introduced to the country by French missionaries in the 1800s. Today, the exportation of Robusta coffee beans remains an indispensable pillar of Vietnam’s agricultural economy. In a determined bid to counteract the exploitative systems perpetuated by globalization, Art Labor implemented sustainable guidelines for the Jrai Dew hammock café. The coffee beans are sourced from a family-run coffee farm nestled in the Central Highlands, and cultivated by Jarai farmers. By ensuring that these workers can make a living from their small-scale farming endeavors, the collective strives to foster and maintain harmonious relationships among the region’s main ethnic groups, namely the Jarai and Kinh (Viet) people. In this collaborative effort, all agents contribute to the sustainable cultivation of this resource.

Art Labor’s most recent project, JUA (2019 – ongoing), once again dives into the reality of agrarian cultivation in Vietnam, specifically focusing on rice and Robusta coffee. Conceived as a one-day happening, the project’s inaugural iteration unfolded in Saigon Zoo & Botanical Garden, where, alongside the exhibition, visitors were offered Vietnamese coffee and pop-rice snacks. JUA served as a celebration of the harvest wherein individuals could gather and exchange.

A centrepiece of the exhibition, Crack (2019), takes the form of a colossal pile of edible wafers, a beloved Vietnamese snack made with puffed rice grain. Adjacent to the installation sat the mechanical extruder responsible for the creation of this snack, known for its noisy diesel engine. The use of puffed rice bears a particular historical resonance. During the Second World War, approximately twenty thousand Indochinese workers were forcibly dispatched to France, where they were tasked with filling explosive cannon shells with gunpowder. To appease their hunger during their time abroad, they started to cultivate rice in the wetlands of the Camargue region in Southern France. To this day, Camargue remains the sole region in France where rice is cultivated, thus exposing traces of the nation’s colonial past. As the mechanical extruder in JUA’s exhibition space runs, the resonant sound of rice popping intertwines with the echoes of gunpowder detonations. Nevertheless, the wafers remain a cherished snack in the Central Highlands, where people gather around the extruder to engage in conversation. Communal healing is underway.

JUA, 2019-ongoing, performance view, Zoo and Botanical Garden, Saigon, 2019.

Photo: courtesy of the artists

In 2022, the project evolved to encompass a large-scale outdoor interactive installation known as JUA — Sound in the SoundScape. Made in collaboration with Jarai artists, the installation draws inspiration from traditional Jarai musical instruments made with bamboo, designed to be played by the air, the water, and the wind. Historically, such instruments have been found in rice paddies, where their melody prevents wild birds from eating young crops. In Art Labor’s rendition, objects made of bamboo and wood are combined with pieces of iron and steel. The wind sets in motion a harmonious clash between the natural and industrial materials, resulting in an impromptu symphony that serves as a metaphor for the rapid modernization of agricultural practices in the region. The clash also echoes the illusory distinction between culture and nature; and most importantly, it highlights the fact that traditional cultivation methods can persist within a mechanized agricultural framework.

Although its recent works have focused on Vietnam’s two main sources of cultivation and exportation, Art Labor reminds us that “both Robusta [coffee] and Camargue rice involve Vietnamese farmers’ sweat, tears and even blood from the early 1900s to now. And both had been unheard [of] in mainstream news and history.”3 3 - Art Labor, exhibition text for JUA (2019), Art Labor Collective (website), accessed October 13, 2023, accessible online. As an example, the contribution made by Vietnamese Indochinese workers to rice cultivation in Southern France wasn’t widely acknowledged until the early 2000s.4 4 - In 2009, French journalist Pierre Daum published the results of a four-year investigation on the Indochinese workers of the Second World War based on testimonies he collected from survivors. See Pierre Daum, Immigrés de force. Les travailleurs indochinois en France (1939 – 1952) (Arles: Éditions Actes Sud, 2009). Through its multifaceted projects, Art Labor provides a space for visitors to (re)connect with the land and offers insights into sustainable agricultural practices and artmaking. Though deeply rooted in historical truths, the collective also underscores how myths and folktales can be relevant when trying to comprehend the implications of colonization and industrial extraction in agrarian communities. In a context in which forests and their inhabitants are transforming into dew, Art Labor emerges as a pathfinder

animated by hope.

An emerging curator and art writer based in Tkaronto/Toronto, Sophie Dubeau Chicoine roots her work in principles of degrowth, radical imagination, and queer utopias. She is pursuing a master’s degree in visual studies at the University of Toronto.