Photo: courtesy of the artist

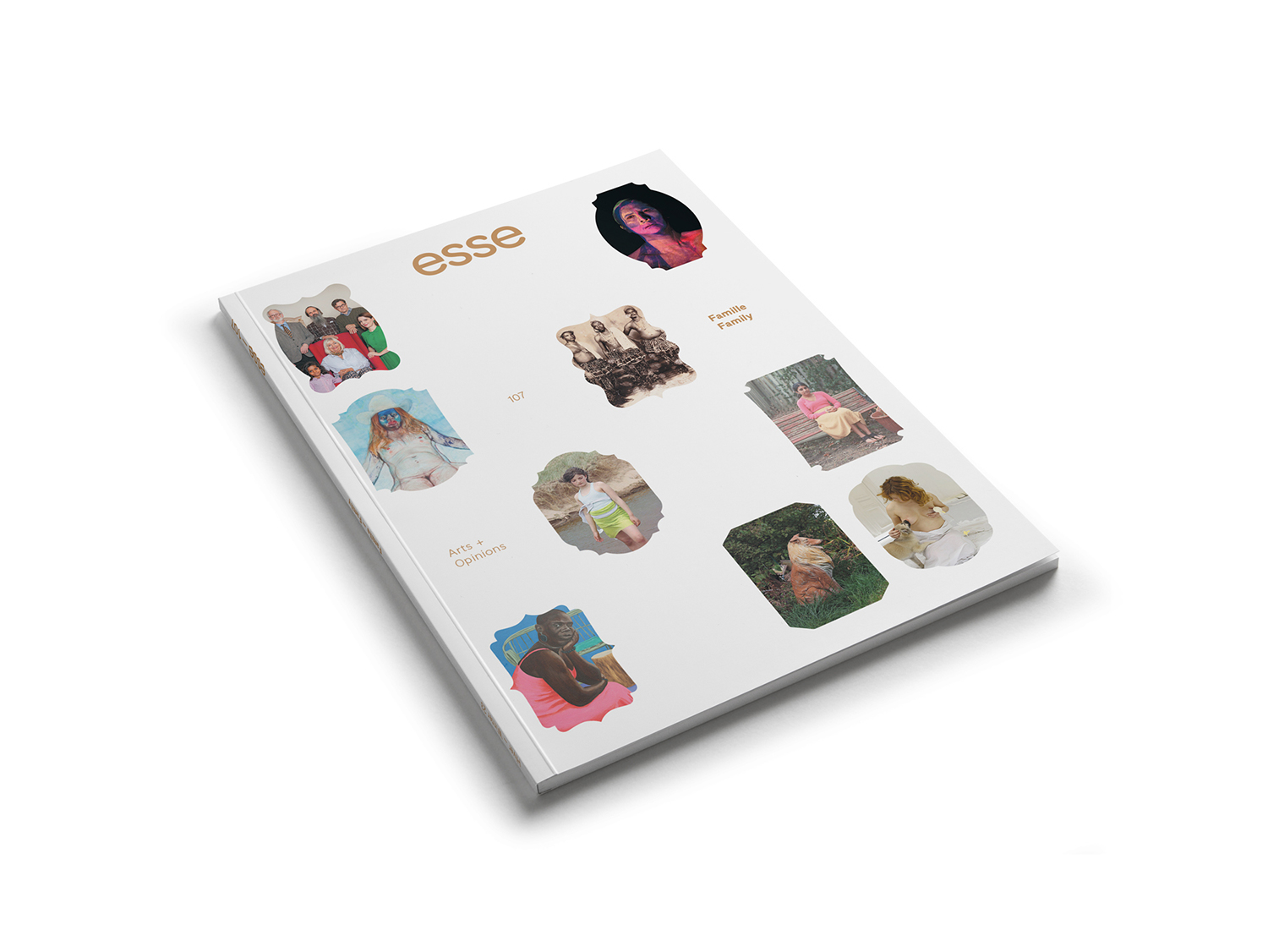

Whose Family Portrait?

From these moments of familial memory, we might attempt to fill in the gaps to complete a story of which a picture can only show a piece. Writing about family photographs as objects of display, the feminist scholar Sara Ahmed notes, “We need to ask what gets put aside, or put to one side, in the telling of the family story.”1 1 - Sara Ahmed, “Sexual Orientation,” in Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 90. In other words, although photographs representing families are omnipresent in visual culture, the range portrayed is generally limited to so-called traditional families. This limitation can encourage a series of reflections about alternative perspectives on representations of family structures. Given that the genre of family portraiture is so often discussed within the history of amateur and professional photography, the concept of family — what it is commonly defined by and what it has the potential to be — naturally intrigues numerous queer artists, including JJ Levine, Jamie Diamond, and Naima Green. Using the family portrait as a foundation in their respective lens-based practices, Levine, Diamond, and Green expand upon the traditional classifications of “family” to portray the multitude of family structures that exist in queer communities. Not only does their work exceed the limitations inherent to conventional photographic practices, but they also contribute to the countless definitions of family in order to reveal the promises for queer familial futures. Both Levine and Green stand in support of their fellow LGBTQIA2S+ communities while representing them as authentically as possible, whereas Diamond’s practice subverts the normative understanding of a family unit.