Bookworms, Arprim, centre d’essai en art imprimé, Montréal, 2012.

Photo : Caroline Cloutier, permission de | courtesy of the artist & Arprim, Montréal

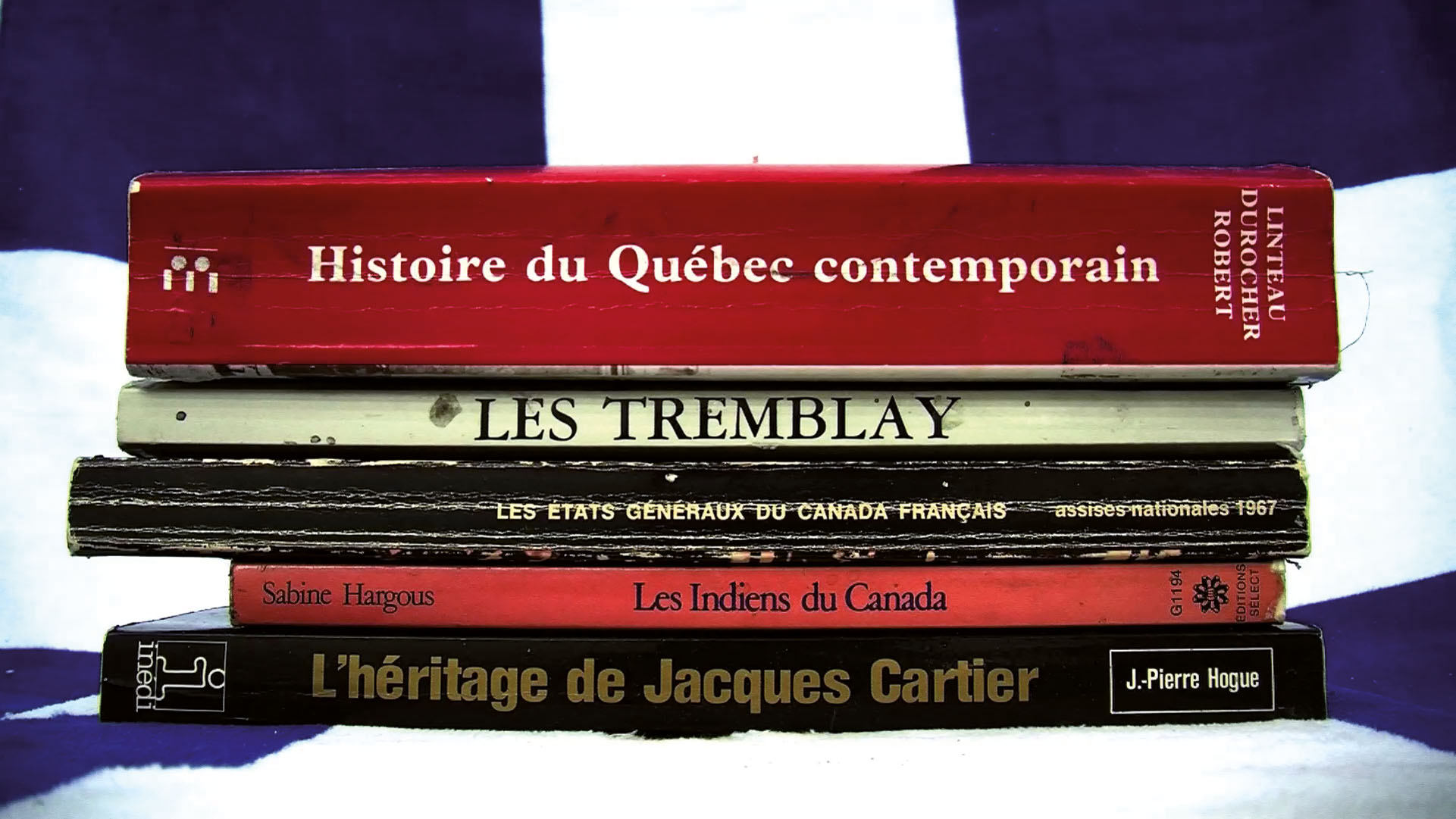

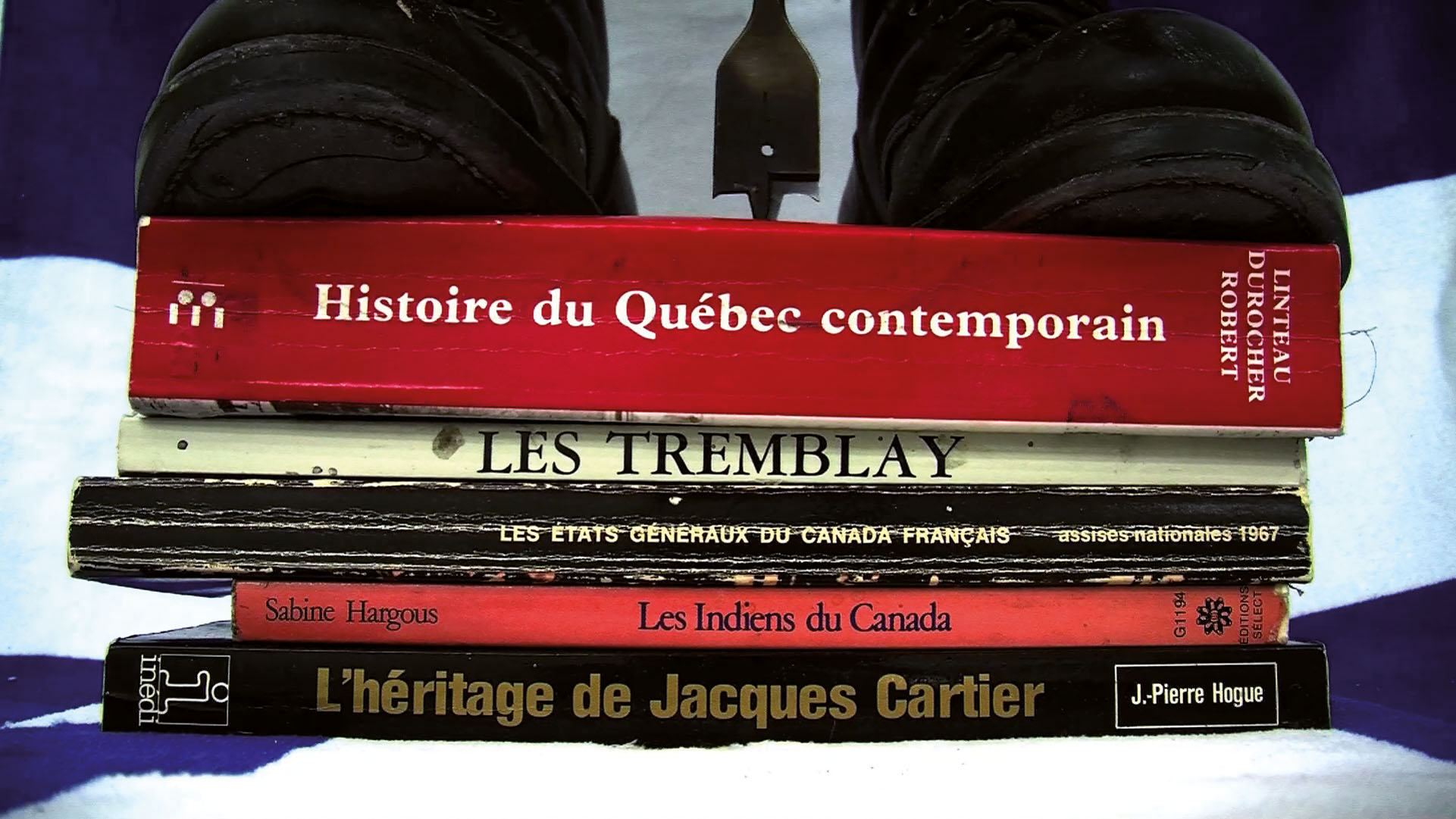

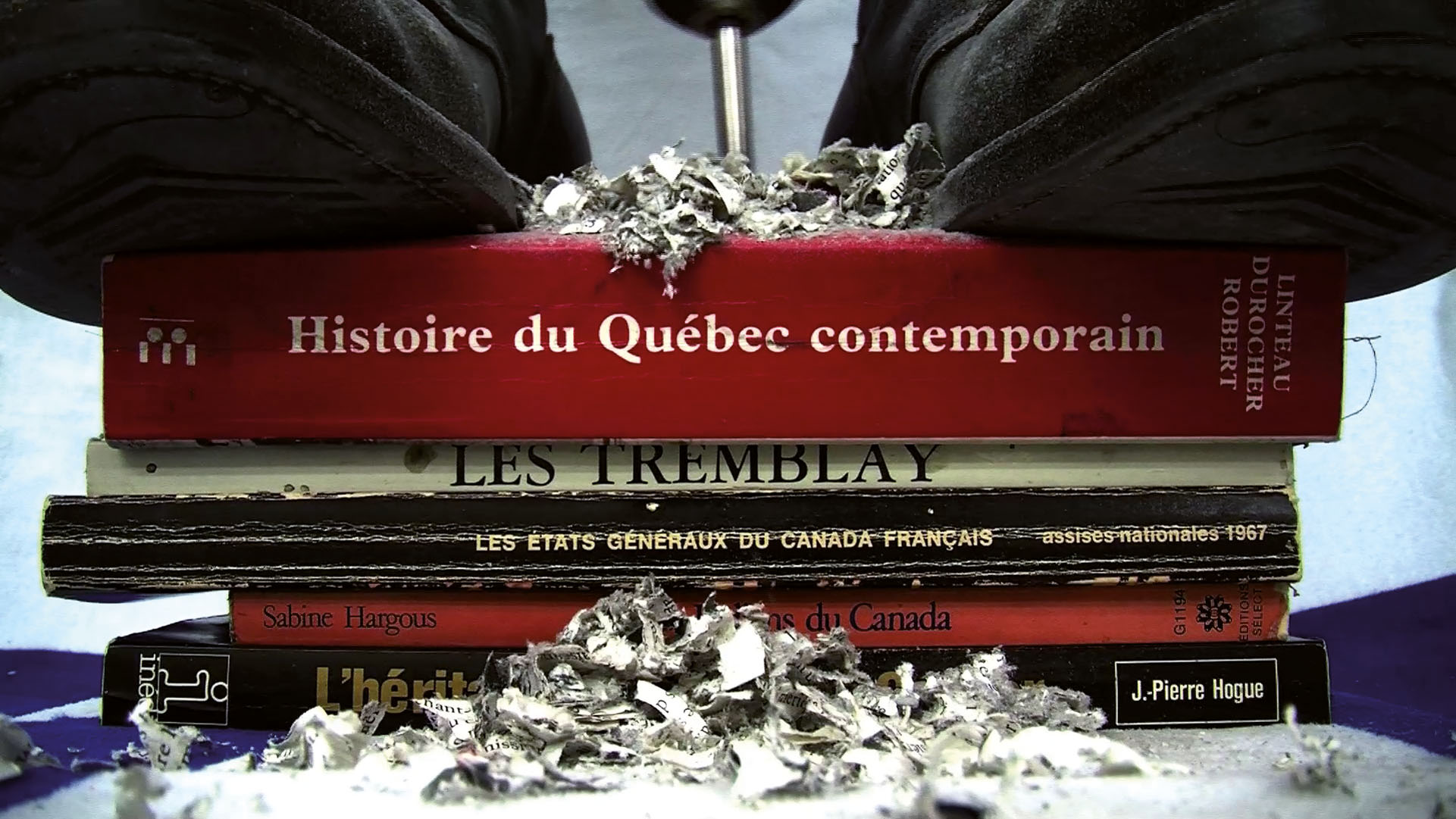

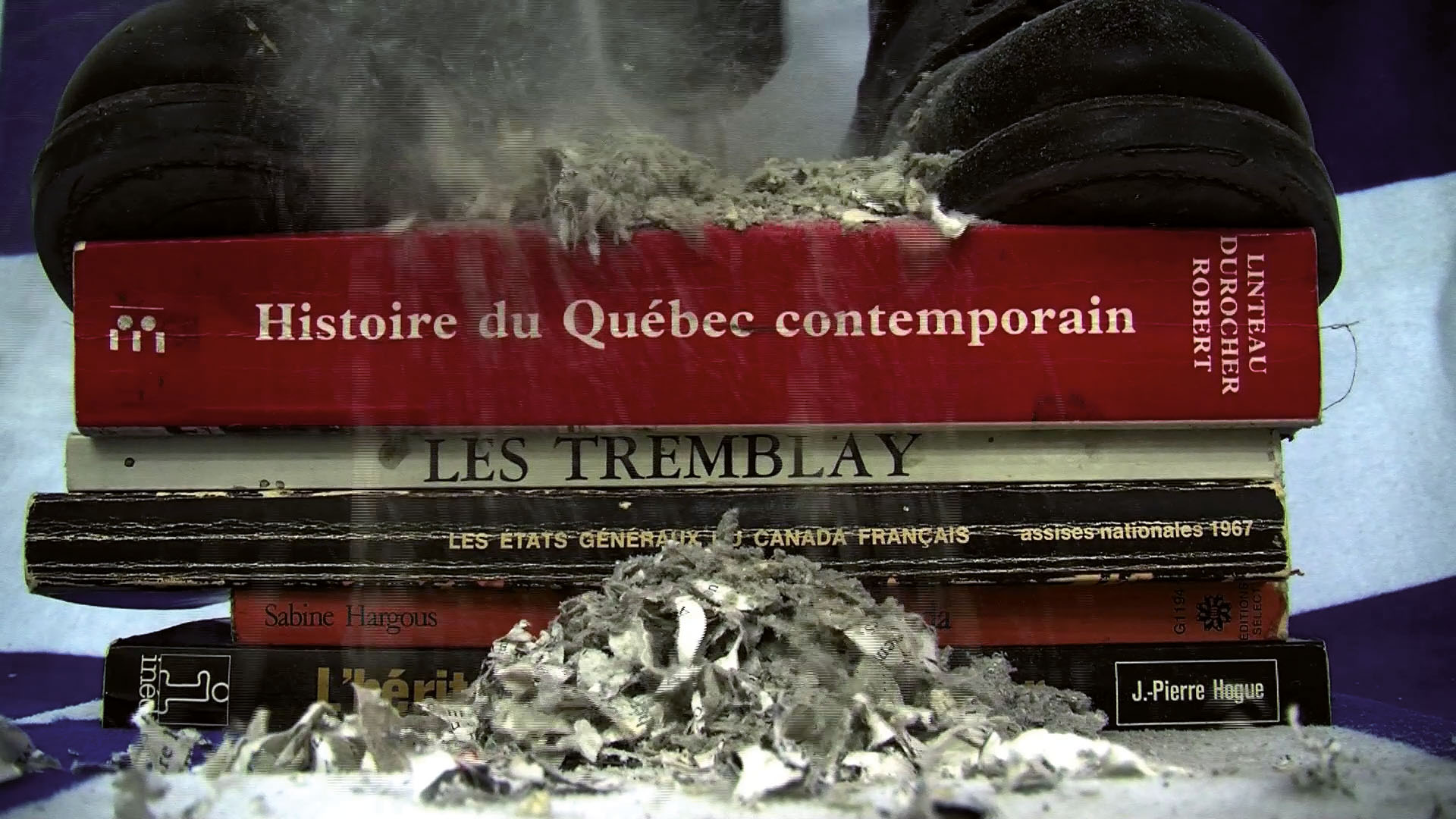

Against a backdrop of fleurs-de-lis, a pile of books reveals the titles of politicians’ biographies, historical accounts, patriotic discourses, and other analyses of Quebec society: Cité libre, L’Énigme Charest, Le Goût du Québec: l’après-référendum 1995, L’Exécution de Pierre Laporte, Nègres blancs d’Amérique, René Lévesque: Oui, and others. This is how volumes charged with meaning appear in Étienne Tremblay-Tardif’s video series Minutes du patrimoine (2012 – 13): stacked like bricks, like the storeys of a building. Tightly framed, projected on the far wall of the gallery,1 1 - The work was presented in the solo exhibition Bookworms at ARPRIM, from November 2 to December 8, 2012. they take on a solid, monumental aspect — at least until the artist’s worn heavy-duty work boots enter the frame a few moments later. The larger-than-life artist places his giant feet firmly on the books, which shift under his weight. He picks up an electric drill, points the tool’s tip into the top of the pile, and turns it on, boring directly into the historical matter. Slowly, stories and accounts from the so-called collective memory are reduced to shreds, with “the typeset pulp churned out again as shavings.”2 2 - Étienne Tremblay-Tardif, quoted in “Étienne Tremblay-Tardif: Bookworms,” ARPRIM, www.arprim.org/programmation/2012-2013/229-etienne-tremblay-tardif-bookworms.html (our translation). Having drilled through the tomes from top to bottom, the artist exits the frame, leaving behind him the vestiges and ruins of his destructive gesture.

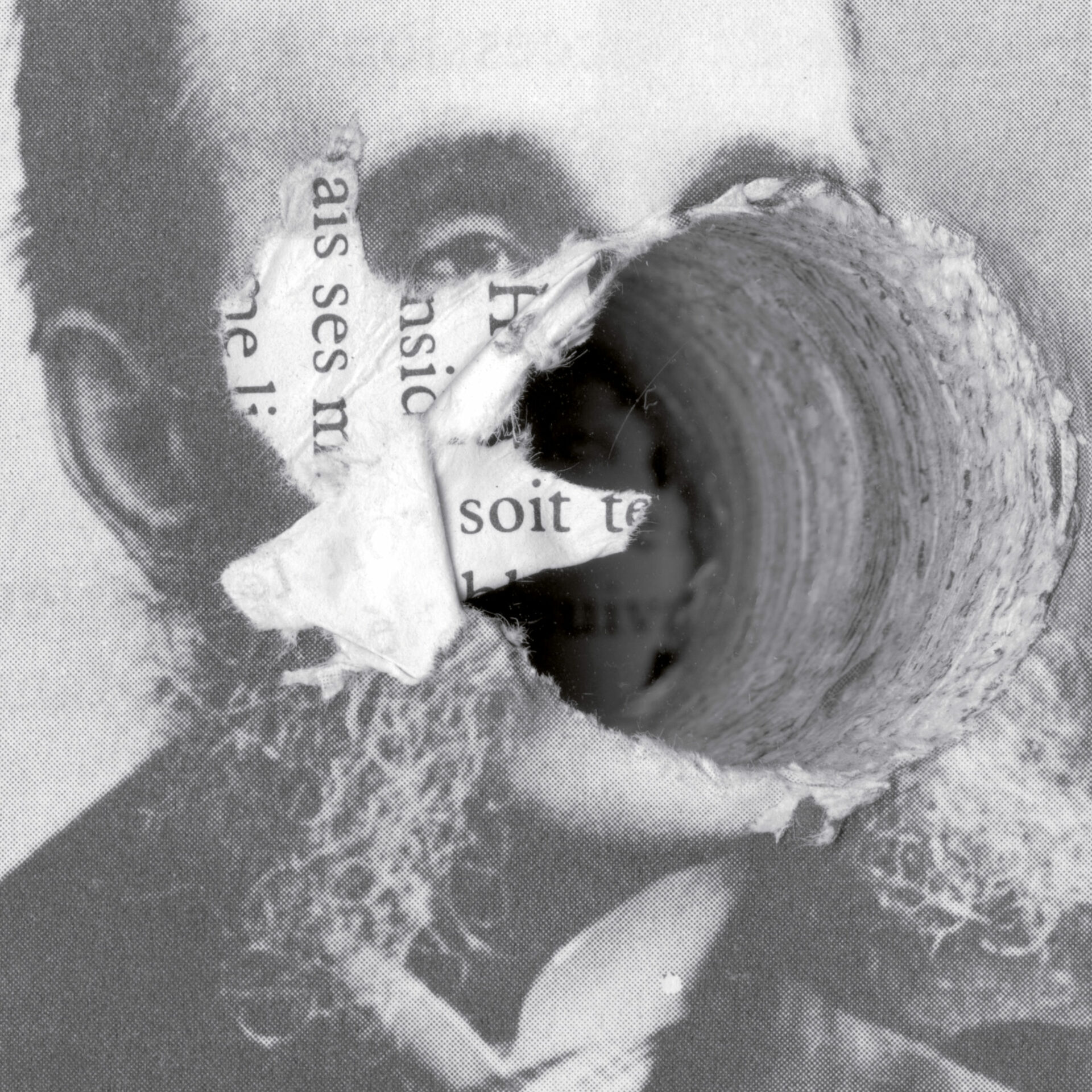

Bookworms / Portraits commémoratifs (1867-1929) : Félix-Gabriel Marchand

(1832-1900), 2012.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Yet the project doesn’t conclude here. The artist returns to contemplate what he can create with the remnants of his work. In one of the hole-riddled books,3 3 - A used copy of P.-A. Linteau, R. Durocher, and J.-C. Robert, Histoire du Québec contemporain: de la Confédération à la crise (1867-1929), vol. 1 (Montreal: Boréal Express, 1979). he discovers the faces of important historical figures ravaged by the rotations of the drill. These he digitizes, enlarges, and reprints to present them as a gallery of mutilated portraits titled Bookworms (2012).4 4 - This title was also given to the exhibition presented at ARPRIM in 2012. This series of works exemplifies Tremblay-Tardif’s approach: to bore deep into Quebec’s collective history to find material for new constructions. In the course of his research, he accumulates documentary material, which he selects as much for its content as for its form. His references, which illustrate his specific interest in the socio-political and cultural context of Quebec — its history and political debates — are drawn from newspapers, historical publications, and art history books old and new. Printed matter plays a dominant role in his work, as both a subject for reflection and a process of creation. Using printing techniques, he reproduces the accumulated material, mixing up references by cutting them out, copying them, and superimposing them to bring them back into circulation. His approach could be described as that of an archival artist, characterized, according to Hal Foster, by a will to “turn ‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites.’”5 5 - Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (fall 2004): 22. It is in this manner that the artist stages his research in construction-site installations.

Since 2009, Tremblay-Tardif has been following the trials and tribulations associated with the reconstruction of the Turcot Interchange, a highway interchange southwest of downtown Montreal. The infrastructure is in a serious state of disrepair, yet its imminent reconstruction has been repeatedly delayed, notably since the plans proposed by the Ministère des Transports du Québec have been a constant subject of debate and protests. In parallel with the slow development of this mandate, Médiarchéologie: matrice signalétique pour la réfection de l’échangeur Turcot (2009–) has, over an extended time frame, generated a corpus of artworks that have evolved at the same pace as the infrastructure project to which they refer. The artist has created a journal of prints, comprising images and documents collected during the course of his research as new political decisions have been made, new cost estimates projected, and new articles published. The already printed pages are thus reclaimed, reused, and reprinted. Texts and motifs cover the entire surface of both sides of the pages, some of which have holes or elements in relief. Thus, the pages acquire a new dimension, passing from print to structural object.

Bookworms / Les minutes du patrimoine : Québec contemporain, les Tremblay, les États généraux, les Indiens et Jacques Cartier,

captures vidéo | videostills, 2012.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

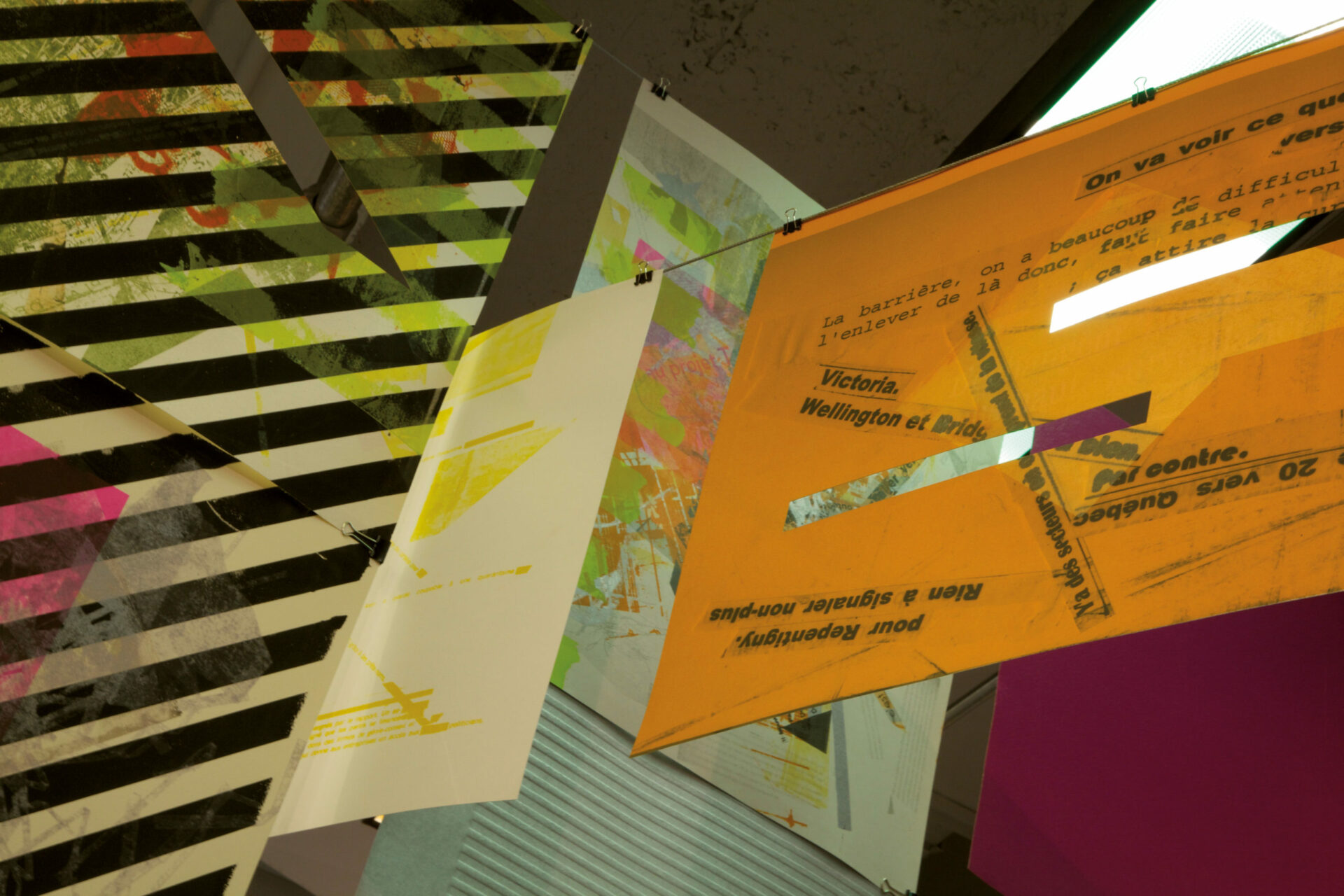

On occasion, the artist has used these prints as a way to present the various stages of his project in the gallery context.6 6 - Notably in the exhibition Ignition at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery in May 2011, and more recently, in May 2013, as part of the master’s thesis group show at Concordia University’s MFA Gallery. The project will be presented again in January 2014 at the artist-run centre Presse Papier in Trois-Rivières. Each time, the mode of presentation is different, calling to mind roadwork sites or interchange ramps, with the pages suspended overhead on a network of crisscrossing cables. Emerging from the whole are colours and forms quickly associated with those seen on the roads of Quebec throughout the summer season: the neon oranges and yellows that signal the numerous detours that drivers must follow. Yet these are also the forms and “pure colours” that one finds in the abstract geometric works made by the Plasticiens in the 1950s and 1960s, the same works that decorated Montreal’s metro stations at the start of Expo 67, when the city was an enormous construction site. Médiarchéologie is therefore a reminder that the Turcot Interchange, today almost in ruins, forms part of the formal research that characterized the modernist period in both the visual arts and architecture. Following in the footsteps of architect, artist, and author Melvin Charney, Tremblay-Tardif considers construction not as an autonomous assembly but as a focal point in the relationships among humans, events, and the media.

Built in 1966, the Turcot Interchange is one of the megastructures representative of the modernist ambitions that marked Montreal in the 1960s. Even the architectural concept of the “megastructure,” designating a huge structure composed of various elements that can be adapted or expanded in accordance with future needs and desires, emerged in the modernist era. Reyner Banham even characterized Montreal, as it was at the time, as a “megacity” due to its major architectural projects interconnected by networks of roads and underground passages.7 7 - Banham devotes an entire chapter to Montreal in his book on megastructures. Reyner Banham, “Megacity Montreal,” in Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), 105–29. Considering the Turcot Interchange as a megastructure thus invites us to return to its design context: it was one structure among many in a Montreal undergoing massive transformation on both an architectural and a social scale. Médiarchéologie also echoes a form of megastructure; the installation comprises several independent elements that can be relocated and reinstalled in new contexts according to the spatial configuration of the exhibition space. On a smaller scale, the design is reminiscent of modular furniture. The work addresses both the renovation of public infrastructure and the social organization that ensues: motorists often take the Turcot Interchange to commute between residential neighbourhoods and the city centre. Like the interchange, the modern houses that sprang up in the suburbs in the same period require their own share of renovations. For this, furniture and materials might be picked up at the IKEA located on one of the nearby highways, with shoppers possibly even taking the interchange to get there. It is inevitable that all constructions need renovating or restoring at some point, not only to repair material damages but also to satisfy new needs and visions.

Médiarchéologie : matrice signalétique pour la réfection de l’échangeur Turcot, Galerie MFA, Université Concordia, Montréal, 2013.

Photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Whilst a storm of allegations of corruption and collusion rages at the Commission d’enquête sur l’octroi et la gestion des contrats publics dans l’industrie de la construction (the Charbonneau Commission, which is looking into the awarding and management of public contracts in the construction industry), Médiarchéologie evaluates the Turcot reconstruction project from a critical perspective. Through its blend of history and current affairs, the work gives rise not to solutions but to questions, which appear on the surface of the structure proposed by the artist, as the documents to be scrutinized constitute the very material of his constructions. His position seems complicit with the intentions expressed on June 29, 2013, by anthropologist Serge Bouchard, who was claiming that he wanted to run for mayor for Montreal: “My program is extremely simple. It is deeply rooted in history, but it is oriented toward the future, toward new heights.”8 8 - Bouchard’s sardonic message was broadcast on the program C’est fou la ville on June 29, 2013, on the Première Chaîne de Radio-Canada. It was also captured on video and can be viewed online. “Serge Bouchard, candidat à la mairie de Montréal,” Vimeo, http://vimeo.com/69282539 (our translation). Tremblay-Tardif’s piece could well belong in such a program: it calls for a form of governance and politics that would reflect on history in order to orient current and future choices.

Médiarchéologie : matrice signalétique pour la réfection de l’échangeur Turcot, depuis 2009.

Photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

This reflection equally implies a questioning of the kind of history that is commemorated or celebrated within the framework of public projects. The interchange, for example, is named after Philippe Turcot (1791-1861), a merchant and owner of the lands on which the Turcot village (one of the working-class neighbourhoods running alongside the highway) was built. In keeping with this tradition of naming public buildings and with the intention of giving meaning to a new establishment, Tremblay-Tardif has created Hôpital Maxime-le-Jaune (2012–), a name which he also suggests for the hospital that will be built in Baie-Saint-Paul in the coming years. The current hospital has been earmarked for reconstruction as a result of studies concluding that it might collapse in the event of an earthquake. Formerly known as Hôpital Sainte-Anne, this facility accommodated mostly patients suffering from mental illness as well as numerous Duplessis Orphans until the Commission d’enquête sur les hôpitaux psychiatriques, followed by the Bédard Report in 1962, led to province-wide deinstitutionalization, which brought fundamental changes to a number of hospitals. In memory of its former vocation, which left a significant mark on the population of Charlevoix, Tremblay-Tardif suggests naming the new hospital after Maxime Pellerin, a former resident of the psychiatric institution, which was nicknamed “Le Jaune” (“the Yellow”) for the distinctive colour of its cladding. While participating in the Symposium international d’art contemporain de Baie-Saint-Paul in 2012,9 9 - The theme of the thirtieth edition of the Symposium international d’art contemporain de Baie-Saint-Paul (summer 2012) was Je fixais des vertiges, formulated by curator Serge Murphy. the artist met with citizens to discuss the idea, and he then worked on architectural plans, scale models, and a large-scale drawing, a kind of inaugural banner for Hôpital Maxime-le-Jaune.10 10 - The large-scale drawing was acquired by the Musée d’art contemporain de Baie-Saint-Paul after the symposium ended. Given the trend toward naming establishments after public figures, benefactors, or patrons, commemorating a patient would, in itself, constitute a form of renewal.

Although “renovation” implies “material repairs” and “refurbishment,” the definition of the word also embraces the idea of reform or renewal. At the border between historiography and iconoclasm, reflecting on utopian ambitions and their ruins, Tremblay-Tardif’s work results in constructions that integrate the memory of the places at their origin. Whereas our streets and buildings carry the names of business people, religious figures, and politicians — the same names immortalized in our history books, the artist proposes digging deeper to unearth and expose less glorious and little-celebrated histories, histories that have equally shaped our society nonetheless.

[Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft]