photo : permission de | courtesy of Jessica Bradley Art + Projects, Toronto

Variations between the traditional fabrication of porcelain objects and contemporary artists’ reuse of the technique provokes a discrepancy, a sense that the material and iconographic dimension of the object is somewhat “out-of-phase.”1 1 - The term is borrowed from Giorgio Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?” in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009). It prompts us to examine the nature of this know-how and its artistic and conceptual variations. True to the technical process entailed by the making of porcelain — moulding and casting, assemblage, firing, painting — artists Shary Boyle, Laurent Craste, and Brendan Lee Satish Tang nonetheless subvert the traditional object by exaggerating its ornamentation, transforming the original imagery, vandalizing it, or exposing its material qualities. More broadly, the gap between the origin of this manual know-how and its re-actualization in contemporary artistic practice cannot be dissociated from historical and socio-economic contingencies. Indeed, from porcelain’s first production in the Far East and then in Europe a few centuries later, these contingencies have determined aesthetic and symbolic dimensions that the approach of these three artists compels us to re-examine. Metaphorical rather than narrative, the works of Boyle, Craste, and Tang reiterate a material and iconographic vocabulary that showcases porcelain as the historical archetype of decorative art. With a past steeped in economic conquests, the porcelain object testifies to the first mercantile explorations, providing the initial impetus to the opening up of continents, precursor to the current phenomenon of globalization.

Porcelain: Traditional Know-How

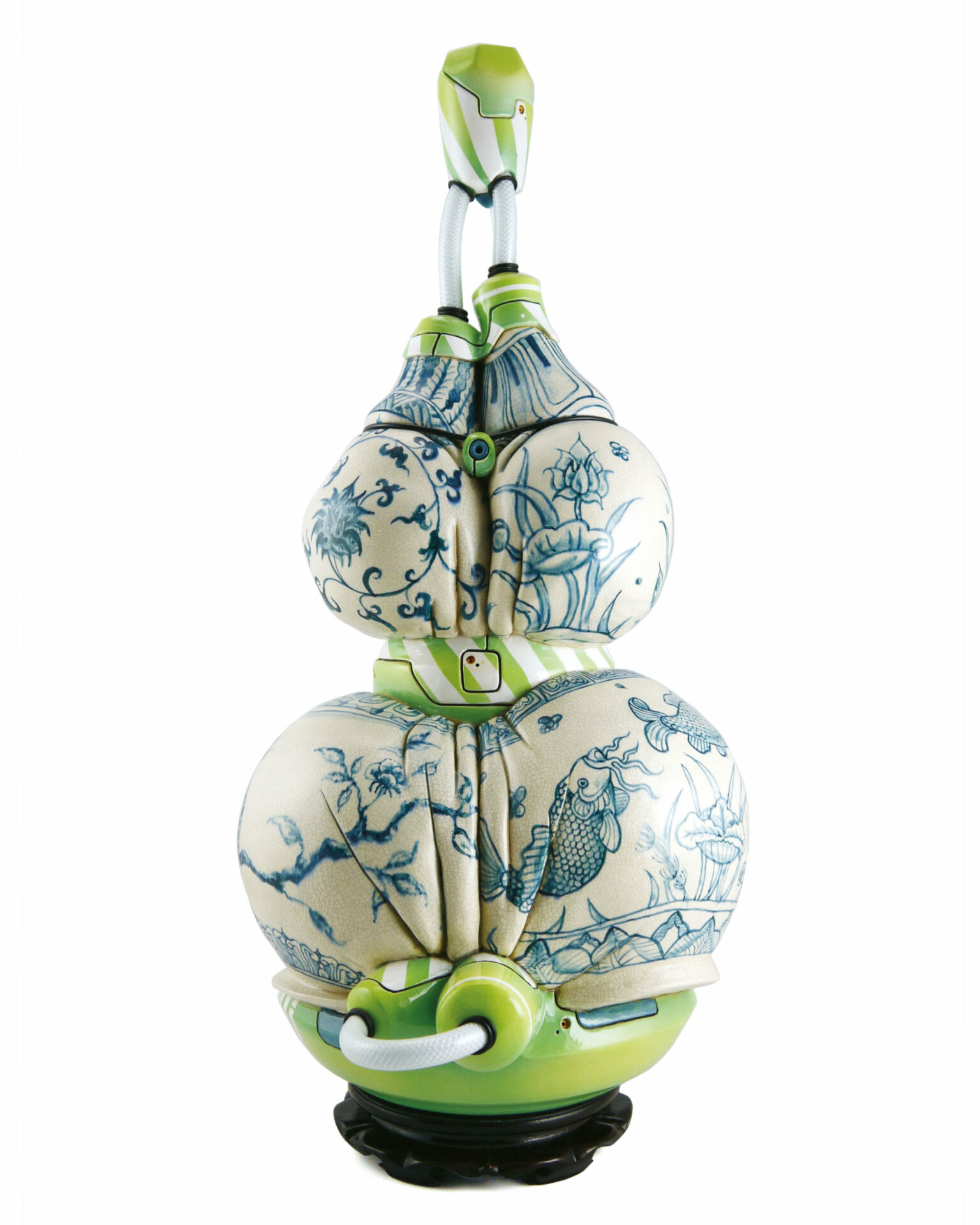

Often called “white gold” for its immaculate whiteness and translucency, porcelain was the object of prolific naval commerce between China and Europe from the 16th to the 18th centuries — before the discovery, by Germany and France, of the recipe for the white ceramic and of kaolin deposits. Each of these countries has developed its own stylistic language and distinct techniques. Boyle, Craste, and Tang have drawn inspiration from these particularities, to the extent that their works may even be distinguished by a predilection for one or the other of these decorative styles: the figurines in Boyle’s Porcelain Fantasy refer to the techniques developed in Meissen2 2 - A technique developed by the Meissen manufactory used by Boyle in the production of her pieces includes lacework on porcelain, a technique that consists in placing lace previously soaked in liquid porcelain directly on the figurine. When fired, the fabric burns away, leaving only its imprint on the ceramic. The Meissen manufacturer is also recognized for the brightness of its colours and for the mythological group scenes of Johann Joachim Kändler — a master sculptor who made the manufacturer’s reputation when he joined in 1730. These group scenes were particularly influential on Boyle’s treatment of mythological subjects in her work. — rococo ornamental styling marked by lacework and the proliferation of authentic flower motifs, as in Snowball (2006) — while those of Craste are inspired by the history and techniques of Sèvres. This manufactory, founded by Madame de Pompadour for the royal court in the reign of Louis XV, exemplifies the ideological framework that governed porcelain production. Themes in Craste’s Iconocrash series (2010) suggest the vandalism and destruction of decorative objects belonging to the bourgeoisie and aristocracy during the French Revolution. The iconography in Tang’s pieces, on the other hand, reflects that of the porcelain produced during the Ming dynasty in the 15th century. Traditionally rendered in hues of blue and white, these flower and plant symbols and motifs, along with the figure of the dragon, have since served to historically identify and inscribe these objects. Tang’s Manga Ormolu series (2009) juxtaposes these now standard Chinese visual elements with indeterminate and unidentifiable objects taken from Japanese Manga, now so popular in both the East and the West, highlighting a tension between these two Far Eastern icons. Manifestly, then, while subverting the tradition of the decorative object, these artists are nonetheless upholding it through the replication of artisanal techniques.

Laurent Craste, Iconocrash 1, 2010.

© Laurent Craste / SODRAC (2011)

photos : Olivier Bousquet, permission de |

courtesy of Galerie [sas], Montréal

Laurent Craste, Iconocrash 4, 2011.

© Laurent Craste / SODRAC (2011)

photos : Olivier Bousquet & David Bishop Noriega, permission de | courtesy of Galerie [sas], Montréal

Intervention: A Distanciation Technique

While manual know-how prevailed in the preindustrial era, it regressed considerably in Europe and North America during the late 19th century as a consequence of the mechanization, standardization, and assembly-line work brought on by industrialization. Also, by maximizing production, industrialization altered the aura of nobility surrounding porcelain and the decorative object, now considered kitsch. The post-industrial era of new technologies distinguishes itself from this mechanized world by, among other things, the difference between manufacturing and action. Hannah Arendt establishes the distinction between the manufacturing of an object, whose final form is clearly set forth in advance and defined by its completion, and action, a completely transient process in itself, which in contrast never leaves behind a final product.3 3 - Hannah Arendt, “The Crisis in Culture: Its social and its political significance,” Between Past and Future, enlarged edition (New York: Viking Press, 1968; repr. Penguin Books, 1977). Our conception of history testifies to this ideology: history, like nature, is a material for human beings to act upon.

© Laurent Craste / SODRAC (2011)

photo : David Bishop Noriega, permission de |courtesy of Galerie [sas], Montréal

(pregnant woman), 2004.

photo : © Rafael Goldchain, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

photo : © Rafael Goldchain, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

This potentiality for action comes through especially in the metaphorical tenor of the three artists’ explorations. The interventions on the traditional decorative object allow one to observe a symbolic action whose effectiveness in “showing things as an act”4 4 - Aristotle had already given metaphor this heuristic and critical function in his Poetics. has the effect of reinforcing the critical dimension of the works. The act of revealing the material or the object “as if animated” is suggested, on the one hand, by highlighting the material specificities of porcelain — its suppleness and fragility, and on the other, by the personification of the object, the anthropomorphism of the work, as explicitly evinced in Craste’s Iconocrash series. Violated and vandalized by an array of tools — hammer, arrows, nails, and baseball bat — the vases and chalices in this series simulate the impact of “instruments of torture” on the porcelain. It is a destructive act.

In Boyle’s work, actions taken to distantiate the porcelain object from traditional artisanry are apprehended differently, through the “super-realist” physical traits5 5 - Louise Déry (ed.), Shary Boyle : La chair et le sang/Flesh and blood (Montréal: Galerie de l’UQAM, 2010), 122. of her miniature sculptures, as in Untitled (2004), a work representing a pregnant woman whose dark-ringed eyes betray fatigue. It is also through the enactment of a represented scene that Ouroboros (2006), for instance, renews the iconography of decorative porcelain and examines the figure of the woman throughout history, by showing every motion of the action, broken down as in a photo-sequence. By replacing the mythological figure of the snake eating its tail with the replicated head of a woman, Boyle’s work caricatures the decorative object.Substituting the woman’s body for the serpent’s, the artist breaks with popular mythological imagery, disrupts scenic harmony through the repetitive and improbable hybrid assemblage of various parts of the body — here a woman’s head — and defies conventional ideals of beauty by adding such physical characteristics as freckles. The figurines are thus humanized. As for the works making up Tang’s Manga Ormolu series, their illustration of the Freudian concept of the “uncanny” is also rendered by means of the animated object. The series examines the identity relationships established on contact with the Other, here explored through an analogy between culture and material. And it is through hybridization, through an inevitable rather than chance encounter between traditional porcelain and a futuristic object drawn from Japanese Manga that the socio-cultural dimension of one’s rapport with the other, with the exotic is questioned. Representing porcelain as a supple, malleable material, and plastic as a rigid, unbreakable substance renders the encounter between the two objects conflictual; one intrudes on the other — an intrusion effectively expressed by the metaphors of grafting, prosthetic extension, and excrescence. Critical of the “global village,” Tang’s works propose a reassessment of this problematic in light of history, via a return to the 15th century, when porcelain merchants first took to the sea. As representations of impossible actions, the works of Boyle, Craste, and Tang augment and exaggerate reality. From this point of view, Boyle’s “need to create an alternate world, a vision of what might be magical, beautiful, and fantastic about being human”6 6 - Quoted in Sheila Heti, “Shary Boyle,” in Shary Boyle: Otherworld Uprising (Wolfville: Conundrum Press, 2008) and available online, at www.sheilaheti.net/Shary.html. echoes Paul Ricœur’s sentiments that it is in the imagination that one tests out one’s power to do, that one measures the “I can.”7 7 - Paul Ricœur, From Text to Action: Essays in Hermeneutics, II, trans. Kathleen Blamey and John B. Thompson (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1991). / Du texte à l’action. Essais d’herméneutique II (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1986), 250.

Brendan Lee Satish Tang, Manga Ormolu Ver. 4.0-k, 2010.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Brendan Lee Satish Tang, Manga Ormolu Ver. 5.0-k, 2011.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Governed by the logic of fallibility, like any recipe, artisanal know-how functions on the empirical basis of trial and error. The artistic productions of Boyle, Craste, and Tang incorporate this principle in their approach. It is for this reason that their porcelain work eludes the danger inherent to the technical mastery of the medium, whose preeminent virtuosity can out-pace intuition and spontaneity. Because accident, chance, coincidence, detail, and the reiteration of technical artisanry are at the heart of artistic production suggests a transgression of this know-how: traces of the artist’s hand left obviously visible, fine cracks in the porcelain, thick daubs of material in Boyle’s work, porcelain vases and containers having lost all use-value in Craste and Tang’s work — all these imperfections are the fulcrum for articulating an un-knowing artistic activity, a tension required of the work’s critical dimension, “a strategy by which incompetence opens the way to a new regime of competence.”8 8 - Élie During et al., In actu. De l’expérimental dans l’art (Dijon: les presses du réel, 2009), 16. (Our translation.) By creating obvious imperfections, affecting the material presentation and conventional iconography attributed to the porcelain object, these works prompt us to identify “elective affinities” and to consider the historical, ideological, and socio-economic contingencies that have governed the emergence of this know-how and its production. Recalling the technique and materiality of the decorative object within contemporary artistic practices enables us not only to envisage the critical dimension of these works but also to apprehend their full heuristic import.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]