This second edition of The New Museum Triennial1 1 - The event took place from February 15 to April 22, 2012, at the New Museum in New York. owed much of its interest to the fact that its theme, “The Ungovernables,” coincided so perfectly with urgent preoccupations of the time. With mine, in any case, as I was visiting New York just as the student strike was entering its fourth week. Events that followed in Quebec, with the popular uprising broadening into a general protest against the neoliberal regime, would also reveal the not-so-underground connection with the Occupy movement that had marked the fall of 2011, from Victoria Square in Montreal (rechristened “Place des Peuples”) to Zuccotti Park in New York. Despite local authorities’ ban on occupying venues, the outrage, even muted, finally resonated again and would find other occasions to manifest itself.

In addition, the context of my visit to New York offered another prism through which to view the Bowery street exhibition in a favourable light, since it took place at the same time as “Art Week,” an event that gives priority to the commerce surrounding art fairs, from the prestigious Armory Show to more recent fairs, such as Pulse and Scope, that are attempting to carve out a place in the market. Art, having become an ideal safe investment, does not seem to have suffered in the slightest from the economic crisis. Anyone frequenting such events is aware of their substance and willingly admits that it is here, after all, that art trends of the world are played out. Obviously, an institution such as the New Museum cannot be unconcerned2 2 - Katie Kitamura, in her comments on the exhibition, mentions the history of the museum’s complex relationship with private and corporate financing in Frieze: Contemporary Art and Culture, No. 147 (May 2012), 219., but to see an exhibition of works openly critical of political and socioeconomic realities gave one hope and proved a good hedge against cynicism.

The incisive tone of this edition of the Triennial, with its selection of 34 artists (and artist groups) in their thirties from all over the world and who had never exhibited in the United States before, also contrasted with the Biennial going on at the Whitney Museum. In its 76th iteration, this major showcase of current American artistic production, and symbol of the propitious alliance between the art market and artists’ consecration by museums, failed to raise the least fervency, despite efforts to present bold projects, some even critical of the institution. Eungie Joo, the New Museum’s curator,3 3 - Eungie Joo is curator of education and public programs at the New Museum and was seconded in this project by Gabi Ngcobo. managed a winning proposal in such a context, though the exhibition and the works comprising it had been conceived before the wave of indignation. In bringing together artists born in the 1970s and 1980s, the curator revealed works whose concerns come in the wake of the previous decade’s independence movements. Far from their promise of liberation, these revolutions sometimes gave way to dictatorial military regimes and neocolonialism in a world, moreover, that would be almost completely taken over by capitalism, and thus exposed to financial crises.

As Joo explains in the exhibition catalogue, the title alludes at once to the colonizer’s fulmination against an “ungovernable” people and the dissidents’ call for civil disobedience, refusing what they perceive to be injustice. This dual meaning covers the multiplicity of stances taken by the artists, who variously put forward gestures of resistance, subversion, transgression, or delinquence.

photo : Benoit Pailley, permission de l’artiste |

courtesy of the artist

This was expressed in the materials used in a stunning sculpture by Argentinian artist Adrián Villar Rojas, who had represented his country at the 2011 Venice Biennale. Produced in situ and stretching from floor to ceiling, it figured a hybrid and apparently fossilized robotic device, perhaps meant for space exploration, though it appeared to have been set there since the dawn of time. Its cracked clay contrasted with the museum’s impeccable white cube. Conceiving an artefact in ruins, the artist engaged temporalities so as to confront the museum’s vanity around conservation with the bursting possibilities and endless expansion of productivity and financial speculation — Wall Street’s greed, for instance.4 4 - In tandem with the sculpture exhibited at the New Museum, the artist created a site-specific intervention at the World Financial Centre, a complex of office towers at the heart of the financial district. In an alcove near a staircase, New York artist Abigail Deville’s site-specific installation was instead rooted in the context of day-to-day survival, its materials consisting of found refuse, vestiges of city life as experienced by the homeless, whose itinerancy and poverty compels them to recycle. This Merzbau revisited intended to be more revelatory of the provenance of the materials, more inclined to mix art with the squalid, and thus to forgo, despite the museum context, the concept of the total work of art and its fantasy of insularity. The excess of some may therefore become others’ bare essentials. While it may have been a matter of expense and waste here, the exhibition was also cast in a subversive perspective that countered or forestalled notions of productivity. In her video, Brazilian artist Cinthia Marcelle uses a high-angle fixed shot to frame a street scene that gradually fills with objects and tools thrown in from off-screen. The clamorous jumble becomes a gesture of rebellion against the well-oiled economic machinery, its growth symbolically undermined by labourers’ refusal to work or comply with normal activities. That the authors of these actions are absent underscores the objects’ quasi-subject status, testifying to their surreptitious dominance of the world.

[The Century], 2011.

photo : permission de | courtesy of the artists &

Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo.

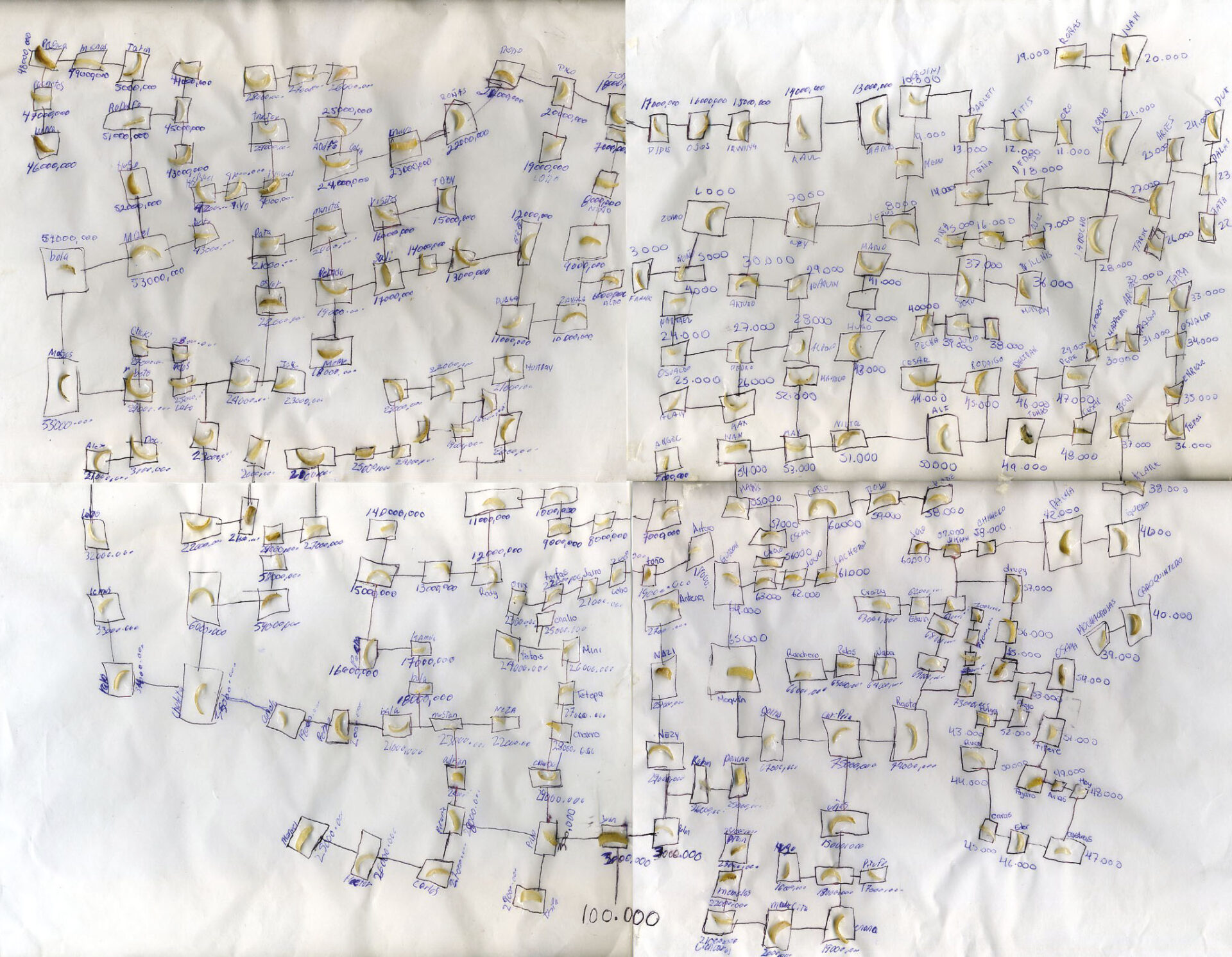

For Pilvi Takala, interfering in the non-artistic working world means disrupting it from within. In Trainee (2008), recreated in the gallery in the form of video and emails, the Helsinki-born artist passed herself off as an intern in an accounting firm where she sat back, did nothing, and waited. She documented her coworkers’ growing unease as they confronted her obstinate refusal to take action, claiming to be doing cerebral work. The latter, it seems to me, is particularly galling because of its abstract nature, which cannot be subject to managerial accountability, as demanded of any business whose existence relies on returns and results. The trainee’s apparent idleness also provides a critical portrait of the artist who — in the wake of Dada, Fluxus, and the Situationists — defines him or herself outside the studio and the (making or selling of) artwork. Mexican artist José Antonio Vega Macotela also intervenes in non-artistic settings. He first made an impact with the installation Habemus Gasoline (2008), an assemblage of stills suggestive of Mexico’s oil production which the U.S. refines for their own use and profit. Time Divisa (2006-2010) is more discrete, yet all the more distinctive with its small-scale montages documenting the exchanges between the artist and the detainees at the Santa Marta Acatitla prison in Mexico City. In exchange for certain items given to the prisoners, Vega Macotela asked one of them, for instance, to take note of the circulation of 100,000 pesos among the prisoners, and in exchange for measures taken toward his release, prisoner El Payasito itemized all possible paths through the prison, marking his footsteps in black when he passed an area under surveillance (whether by guard or by camera). Without denying the humanist dimension of these apparently fair exchanges5 5 - In regard to this project, Chus Martínez mentions that the artist intervenes in “[…] a system that is already governed by an uncompromising principle of mutual instrumentalization,” Artforum, (May 2011), 271. — which by proxy afforded prisoners the possibility of being different subjects despite the penal context, in particular through the attribution of their work — the project was especially interesting for its demonstration of the ways prisoners illicitly bypass their restrictions while also revealing methods of coercion and surveillance in the detention centre.

(El Kamala), Time Divisa, 2010.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

(El-superaton), Time Divisa, 2008.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

It is hardly surprising that several of the works were concerned with finances and the money market, a topic that affects many societies increasingly interconnected by globalization. Thus, the 5,000 euros invested by Bangkok artist Pratchaya Phinthong in Zimbabwe currency in 2009 have been transformed into a growing heap of methodically piled bills as the currency underwent hyperinflationary devaluation. Through this artwork, the bank notes are reevaluated again, this time by the forces of the art market, of which these “ungovernables” have managed to problematize, if not overturn its operations and existence.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]