photo : permission de | courtesy of the artist & TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary

From the outset, I would like to make clear that it is not the idea of painting that interests me so much as painting itself. Objects generally lie at the source of my thinking, and my idea of painting reflects the productions of Eric Cameron, specifically his “Thick Paintings.” These objects allow me to share a few research notes here in the form of a story.

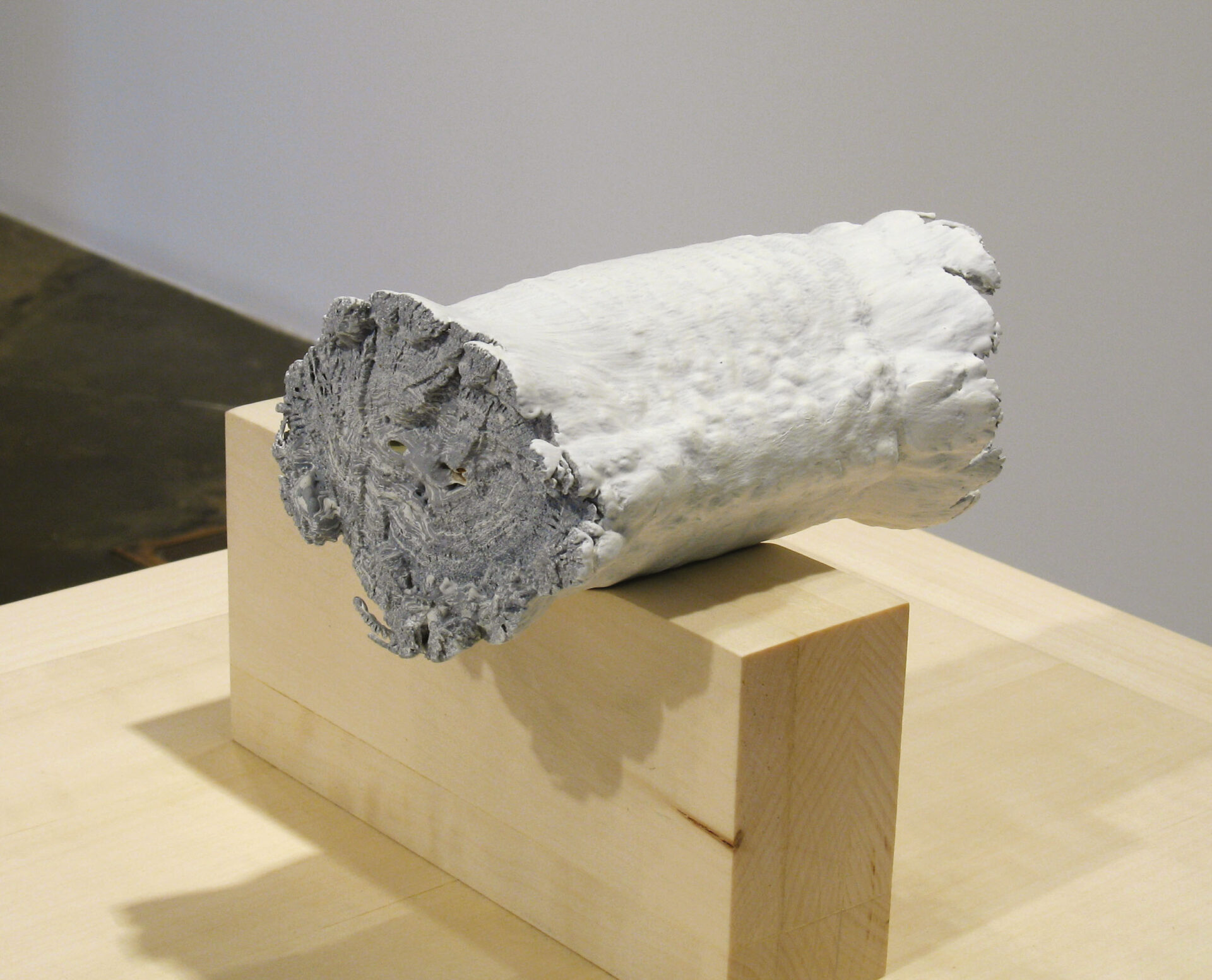

This unique production begins in late April, 1979. An artist selects various objects lying around his apartment — a phone book, an apple, a shoe — and covers them in a layer of gesso. With the application of that first layer, the sacrificed objects’ usual function is obliterated while new monochromes come into being. Next day, he adds a layer of acrylic to each object. The story continues and the layers multiply as the artist takes to this new process. Every day, for ten years, he covers each object. Apple and shoe, soon to be followed by rose, cup, saucer, bottle, gradually take on volume. Eventually, the applied layers submerge surface details. The objects are manifestly changed. Hollows and chinks are filled. Cumulating brush strokes create undulations. Lumps form. Forms are gradually altered. 1,901 layers of paint later, the phone book is no longer the same. Nor is the lettuce or the Danish.

Imagine, if you will, the same process applied to the idea of painting. The concept requires a little imagination, I admit: the idea of painting, in your mind, must take on a tangible form, must be “prehensible” — an idea made object. Choose whatever form you like. One, say, that can sit in the palm of your hand. On the first day of history, it will have been covered with a layer of gesso, corresponding to its inaugural pictorial experience. Successive layers will then have been superposed. Each period in history will have nourished the object, which will have progressively gained in weight, volume, and dimension. Innumerable acquisitions of knowledge obtained in the creation of painting will have coalesced. The painting object’s form, the one now before us, necessarily differs from all prior ones. Indeed, over time, a new object will have replaced the one enveloped in the centre, in a sense containing within itself the process of its own gestation.

As I mentioned before, my notion of painting resembles such Thick Paintings, at least in part because these objects expose the process by which they were engendered. Applying paint to a surface by means of a tool called a brush is one of the most codified gestures in the history of art. In that sense, it is impossible to paint today without considering all that is understood, all that has been seen and is “under-seen”1 1 - The author here refers to the term sous-vus, which, playing on sous-entendu (that which is understood), is borrowed from Jean-François Lyotard, for whom “the least glance is laden with presuppositions, and those things that are understood, which one must term the ‘under-seen’…” Que peindre? (Paris: Hermann Éditeurs, 2008 [originally published 1987]), 11. (Our translation) in art history. The prevailing notion of our time is that all motifs have already been dealt with. So what to paint? Or rather, what to re-present?

photo : permission de | courtesy of the artist, TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary

Eric Cameron, Chlöe’s Raw Sugar (1456), 2004-2008.

photo : TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary, © D.R. / CNAP

The painting object has expanded over the centuries. One may even imagine that it has become so huge that it can hardly be encompassed in a single gaze. Another view is that alongside art history’s global painting object we may imagine its fragmentation, such as to consider the significance of its regional identities and returns to its local history and traditions. With respect to the painting object in Canada, it would seem essential to envisage the idea of painting by considering the knowledge transferred between the generations of its practitioners.

The zeitgeist since the late 1970s no longer favours the grouping of pictorial practices into movements, which could potentially be defined as avant-garde. Yet, to understand the painting object in Canada and to grasp its influences, one must delineate the impact of collective initiatives that have developed throughout the country. To what extent have members of the Painters Eleven influenced the work going on now in Toronto? What impact did the Regina Five have in the Prairies? What part did the works of the Automatistes and the Plasticiens play in transforming practices in Montreal? Moreover, to better understand the circulation of ideas, one would do well to consider the influence of works collected by Canadian museums and to study the circulation of their exhibitions. Directly or indirectly, all this information has a bearing on the concept and identity of painting in the country. So many aspects must be considered that these few words can only touch upon the periphery of our subject — the idea of painting.

Concept is critically important to Eric Cameron’s work. Conceptualism was in fact one of the defining traits of productions at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design (NSCAD), where he taught from 1976 to 1987. Artists like Jeffrey Spalding, Mary Scott, and Garry Neil Kennedy have also developed painting practices in which many layers of material are applied to a support. It would be logical then to consider the idea of painting in Eastern Canada to be greatly influenced by the conceptual approach of the mentors and students who gravitated around the NSCAD, a pivotal centre of research.

Simultaneously, in the western provinces, many artists were founding their practice on a conceptual reappraisal of modernist issues in art. This concern led to reflections on representation that greatly influenced pictorial practice. If one wished to trace the sedimentary layers making up the idea of painting in Vancouver, one would have to consider the contributions of Ian Wallace’s teaching at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, along with his diptychs juxtaposing photography and painting. One would have to examine how Jeff Wall’s photographic tableaux allowed for a reinterpretation of the social and narrative implications of modern painting. One would also have to ask Arabella Campbell, Elizabeth McIntosh, Jeremy Hof, and Ben Reeves what their current work is founded on, ask them which productions shaped the ideas and the formation of their own.

Eric Cameron, Thanatos # 81 (détail | detail), 2011.

photos : permission de | courtesy of the artist & TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary

Among current artists, many painters appropriate historical and archival sources to effect a self-reflexive turn in painting. It is said that painting always comments on itself, that a painting is a space of constant reinvention. The history of painting is in part a re-cognition of its own history, if not its rereading. We know that history is not a static narrative, but rather a malleable material that can be reconfigured. The history of painting, like the Thick Paintings themselves, is a construction. Its process of conception is familiar. Its material — like the knowledge we acquire through the experiences of making engaged in and shared by the artist — coalesces and gradually alters its form, if not the contours of its definition.

Time produces cycles in which questions are revisited in view of resolution. Is the painter’s challenge not to invent new solutions to problems already long posed? Paradoxically, different problems may share the same solution. Take for example the white monochrome, which belongs at once to the history of suprematism, minimalism, and formalism, and is still open to reinvention today. A single formal solution can accommodate several narratives. Each belongs to a particular layer of sedimentation which constitutes the painting object.

A painting leaves marks on the object of its idea. Figuration, for instance, enables the inscription of narratives in forms whose object is their own memory. Some paintings comment on the conditions of their (re)production. Because painting is an institution with a long tradition, it seems entirely legitimate for painters to highlight and examine the resources that have accrued in their repertoire over the course of time.

Painting has been declared dead more than once, but is it not rather our vocabulary for describing it that is outmoded? Were some ideas not due for re-evaluation? Our conception of space and time changes, not only because our experience differs from that of yesteryear, but also because it builds on what preceded it. Reflecting on re-presentation seems to me to be the essence of painting. In this sense, one could imply that painting today corresponds more closely than ever to the image of Thick Paintings.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]