photo : Philipp Scholz Rittermann, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Do relational practices fall within the scope of a market logic whose purpose is to criticize the presupposition that art is a place of community encounter?

If we are to make a portrait of a generation based on the theory put forth by Nicolas Bourriaud — who fifteen years ago brought together a set of diverse practices under the term “relational” — we can already affirm that his discourse found an environment favourable to its diffusion at the heart of Quebec’s network of artist-run centres.1 1 - Since the beginning, through its network of exhibition, production, and documentation centres and publishing houses, the artist-run centres have provided fertile ground for the expression of counter-culture. These same spaces are now cited as models of artistic autonomy and self-management in the context of globalization. Relational aesthetics possessed everything to seduce this initiated public: by favouring more user-friendly forms of exhibition, it reasserted the value of a facet of artistic creation centred on improvisation and the everyday, while questioning the authority of the white cube in the process of validating works. In temporarily dissociating itself from official exhibition spaces, this aesthetic also assessed the subversive potential of a living art and its implication in public space, without necessarily becoming the standard bearer for social causes or struggles (with which early performance art had been associated in North America).

One must, however, bear in mind the context of production and diffusion into which these new practices were introduced in Quebec, a context vastly different from the one scrutinized by the French curator and art critic. This distinction is essential in understanding the significance of the artistic gestures and actions that ensued here as a result of artists, including several enthusiasts from across the Atlantic, adopting the concept of conviviality at the basis of this aesthetic. First, particularly in Quebec, one must underline that the art market and State are interdependent: culture, in general, is subsidized in order to counterbalance the weakness of the market. Considering the position it occupies in the territory and the level of support it receives from the State, art is doing relatively well.

The quest for autonomy, liberty, and experimentation is therefore quite different for artists who receive funding, as it is for the cultural institutions, organizations, and journals promoting their work. In this context, the government apparatus essentially functions as an economic lever that stimulates and regulates creation, production, diffusion, and risk-taking. That being said, a re-assessment of the eponymous work by Bourriaud is imperative in order to evaluate and consider a posteriori the disparity of contexts raised above,the scope of discourse, as well as its influence on current practices, while taking care to keep the Quebec reality in mind.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In the 1980s, Nicolas Bourriaud published the manifesto Relational Aesthetics2 2 - Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods with the participation of Mathieu Copeland (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002). proposing a new paradigm emphasizing the “experience of social relations.” Even though the work was well received in France, the reception was less than unanimous in North America, particularly in the United States. At the time of its translation in 2002, many critics aligned themselves against what they judged to be an overstated typology.3 3 - Bartholomew Ryan, “Altermodern: A Conversation with Nicolas Bourriaud” in Art in America (March 17, 2009), accessed March 31, 2011, www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-opinions. Although Bourriaud attempted to give us a new insight into our approach to contemporary art while devoting himself to proposing innovative tools of interpretation, it is important to recognize that theories on work (Herbert Marcuse) and communications (Marshall McLuhan), as well as the emergence of social movements in the 1960s had already had a considerable impact on the rapport between the artist and production, modifying the artist’s relationship with the institution.

Rightly or wrongly, what was understood of “relational” practices brought about a certain malaise by dint of working in and with the real, without guidelines or a social charter. To this effect, Bourriaud denies having directed his discourse towards the notions of interactivity and participation that have been ascribed to him. He reiterates that it is rather a theory of form: “the forms that one uses as tools,… that one recharges,… and presents again,” laying stress on the notions of editing, dubbing, and samplingof DJs,withoutaffiliating oneself — in continuity or rupture — with history. In an interview, he emphasizes the modelling of the relationship rather than its convenience, its exchange value.4 4 - Interview between Raphaël Cuir and Nicolas Bourriaud, rebroadcast as a video on the Internet as Mémoires actives, La chaîne d’histoire de l’art et d’art contemporain, accessed March 31, 2011, www.dailymotion.com/video/xh5pfk_entretien-avec-nicolas-bourriaud_creation.

Influences and confluences

When it was published, no such comparable literature existed in Quebec, even though the network of artist-run centres had theorized about this rapport with the other in publications focused principally on performance art.5 5 - I refer the reader to the works Penser l’indiscipline : pratiques interdisciplinaires en art contemporain (2001) published by éditions OPTICA under the direction of Lynn Hugues and Marie-Josée Lafortune; l’Anthologie de l’art performance au-in Canada (1991) under the direction of Alain-Martin Richard and Clive Robertson, as well as Art Action 1958/1998 (1998) under the direction of Richard Martel, both published by éditions Inter of the contemporary art centre Le Lieu, Quebec City. Still today, we conceive differently the notion of community associated with this form of art,6 6 - See Patrice Loubier, Anne-Marie Ninacset al., Les commensaux: Quand l’art se fait circonstances (Montreal: SKOL, 2001). without taking to “communitarianism” (as has often been implied in Hexagone). One must keep in mind that during the 1990s, our imaginative worlds were also shaped by the thought of Anglophone authors commenting on the public and private spheres — notably Rosalind Deutsche — and whose publications put forward a revision and updating of history, supported by post-colonial theories, feminist analysis, etc. With hindsight, it seems evident that many principles separate Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics from cultural studies, in particular in regard to the level of emphasis given by the latter to the contribution of marginal cultures long-neglected in favour of the dominant discourse, or the individual envisioned as a principal figure of social change. Thus, it is hardly surprising that the French author dissociates himself from the interactive or participative aspect: he is more interested in communication strategies than in the question of identity. His most recent publication The Radicant7 7 - Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, trans. James Gussen and Lili Porten (New York: Lukas and Sternberg, 2009). accentuates this disparity. Evoking the metaphor of a root imitating a rhizome, he explains that the question of origin can no longer be posed in terms of nationality, artists now being the new migrants of the planet, where they “take root” and develop in other regions.

So be it! Several artists have undeniably been inspired by the notion of transit, seeking to define a new internationalism and abolish borders — after the fashion of free trade via the Internet and social networks. This, however, hides another more disconcerting reality, marked by the precarious and vulnerable status intimately linked with the condition of thousands of individuals compelled to become “migrants” in their own country or beyond its borders, due to natural disasters or political conflicts that bring about mass movements of populations (phenomena that are on the rise in certain regions of the globe).

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Unlike the pleasurable experience of “taking root” wherever one chooses by exercising one’s freedom of choice — an exclusive feature of capitalist Western societies — what ensues from involuntary movements of populations is rather a gradual impoverishment of the social sphere. This also has a direct impact on the identity and specificity of peoples, as it does on the power of dominant nations, realities too often disposed of in the interest of a shift towards the image of the artist as a cultural tourist. Speaking of social experience as a new paradigm, while continuing to reproduce power relations that justify exclusion or to seemingly hide certain conflicts instead of considering them and integrating them into our reflections, and thus restoring meaning to public space (Deutsche), seems worrying, to say the least.

In this perspective, reverting to the interpretation of the gift as Pierre Bourdieu analyzed it — notably in Outline of a Theory of Practice8 8 - Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007) (new edition revised by the author). and in The Logic of Practice,9 9 - Pierre Bourdieu, The Logic of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Polity Press 1990). two major works in the elaboration of a theory on the social world — seems to provide some possible answers by giving us a better grasp of the concept of reciprocity and the role of timing in an exchange. Taking time into account has also allowed Bourdieu to show that despite the appearance of reciprocity, a dependence takes hold and coexists between the donor and the donee and that this manifests itself in the interval: “The interval between gift and counter-gift is what allows a relation of exchange that is always liable to appear as irreversible, that is, both forced and self-interested, to be seen as reversible.”10 10 - Ibid., 105. Although one strives for balance, gift-giving is not an entirely disinterested act. This reflection is always pertinent and current, all relationships being based on the schema of perception. In this way, returning to our discourse on relational aesthetics, simple flowers offered by an artist become a commodity rapidly coveted by the users of the park in which the action takes place. By reselling the bouquets to buy alcohol, they divert the gesture towards the local economy, thus reversing the situation and in doing so becoming the principal protagonists, a transformation revealing the persistent disparity between the art world and that of the living.11 11 - I direct the reader to an interview relating the intervention of Devora Neumark in Square de la Paix within the framework of Gestes d’artistes in 2001 (OPTICA, 2003).

The experience of the other

In another vein, the performances of Rebecca Belmore, an artist of Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe) origin living in Vancouver, derive from the premise that she is constantly in the interval, that she is not comfortable in the public sphere. In their own manner, her performances synthesize what Bourdieu refers to as habitus, that is to say the deep understanding of an individual experience integrated into an evolving collective history. In fact, her gestures are inspired by a series of gestures carried out by a lineage of women to which she restores meaning, memory. The figure of the heir who incarnates tradition — who “is born of it” (Bourdieu) — and who confers legitimacy in a permanent form in its sphere of action — “a symbolic capital constituted by the artist” — is present in the sum of actions that Belmore reproduces.

Prior to this, the artist fully grasped the concept that she was subjecting to transformation, bringing together new conditions in the form of transactions, examples of which include Awasinkae: On the Other Side, performed in San Diego and Tijuana (1997), as well as Brava! and Sun & I, at Art Forum Berlin, International Fair for Contemporary Art (2003). The same attitude is at the foundation of these two projects in which Belmore identifies with a person of colour on the margins of society, often without official papers. In Tijuana, a native woman she met on the street served as a model for a photo session. She posed in front of colourful walls of a residence, having accepted to participate in the exercise in return for payment. The results are images of immense beauty that imitate identity portraits — frontal views, left and right profiles — and which emphasize the migrant status of the young woman.

photos : Michael Beynon & Philipp Scholz Rittermann, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Transgressing artist etiquette, Belmore paid her the equivalent of several months’ salary, knowing that the woman could never accumulate such a sum of money so quickly by begging. And although the market value of the transaction represents but a fraction of the fee she earned as an artist, the gesture is all the more symbolic and political since it involved a woman of colour whose life course it temporarily affected. The images printed on translucent film (Duratrans) — documents witness to the meeting — were exhibited on the illuminated marquee of an old abandoned theatre in San Diego, close to the US-Mexico border. When the series was shown at the OPTICA centre for contemporary art in 1999, the artist again donated part of her fee to a group of mariachis, invited to play a sad serenade in honour of the native woman during the private viewing. After the serenade, Belmore placed a lit candle on the floor in front of the portraits, symbolically giving back the model her identity (counter-gift) through the significance of ritual, born by the performance.

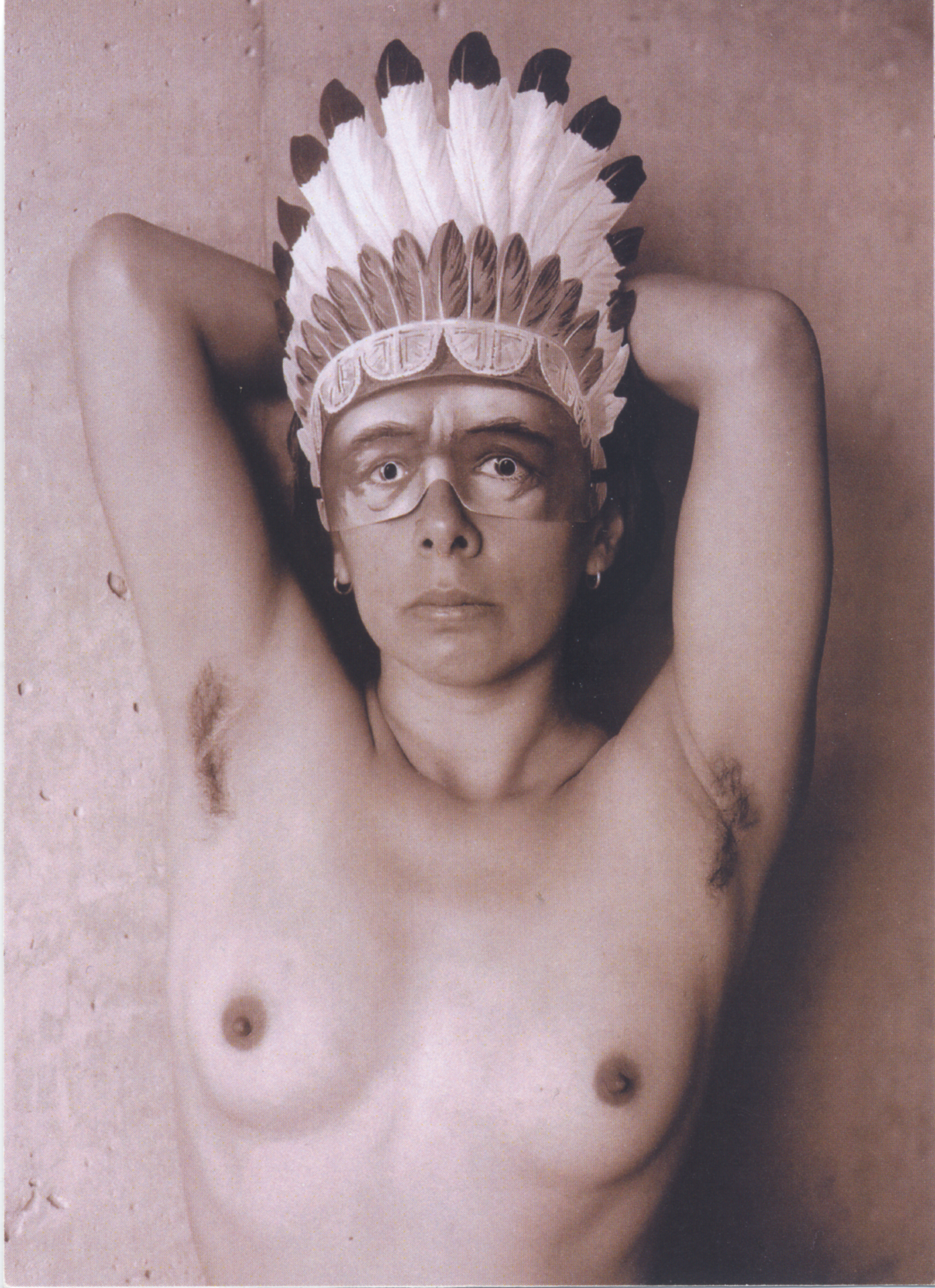

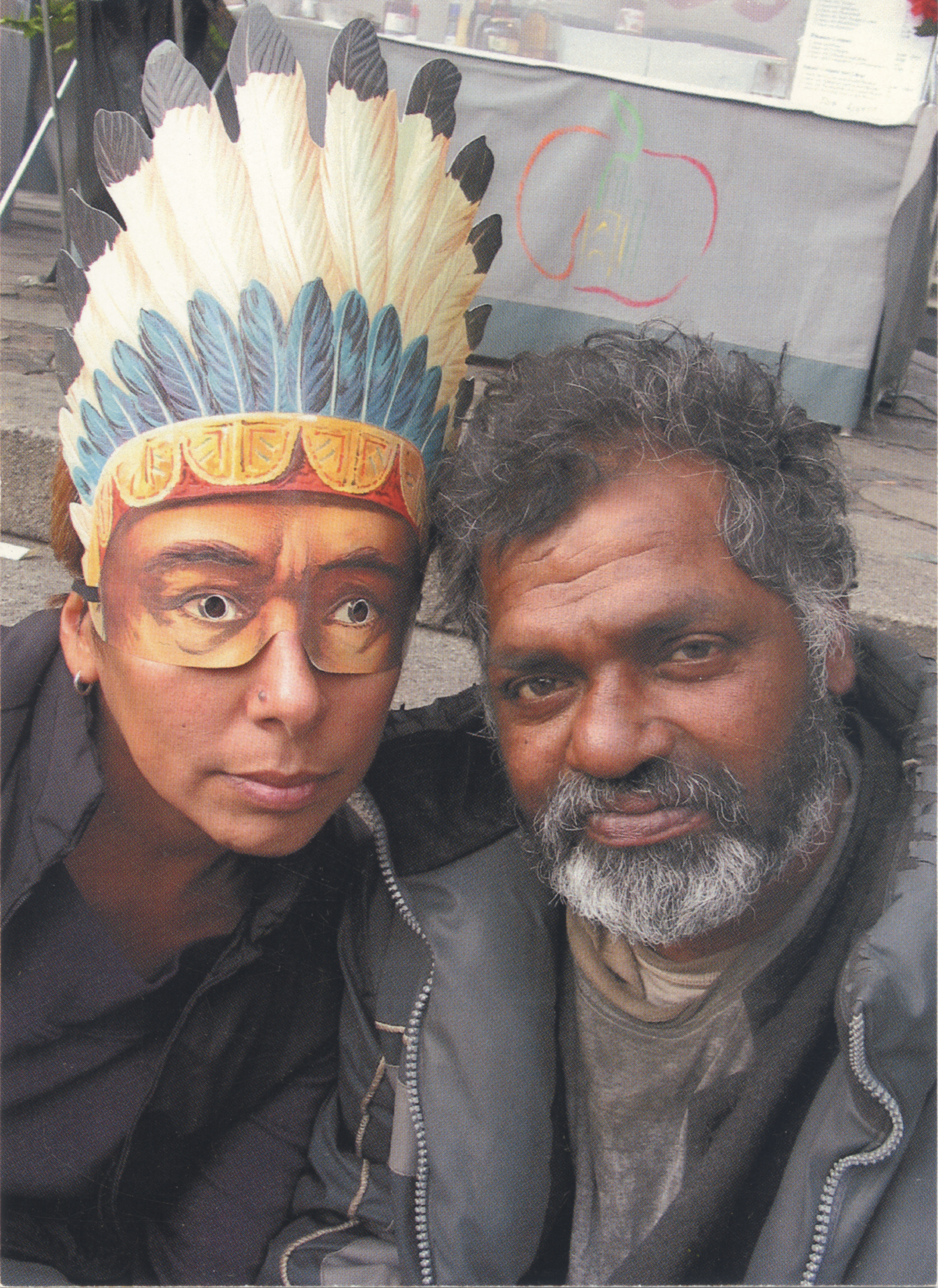

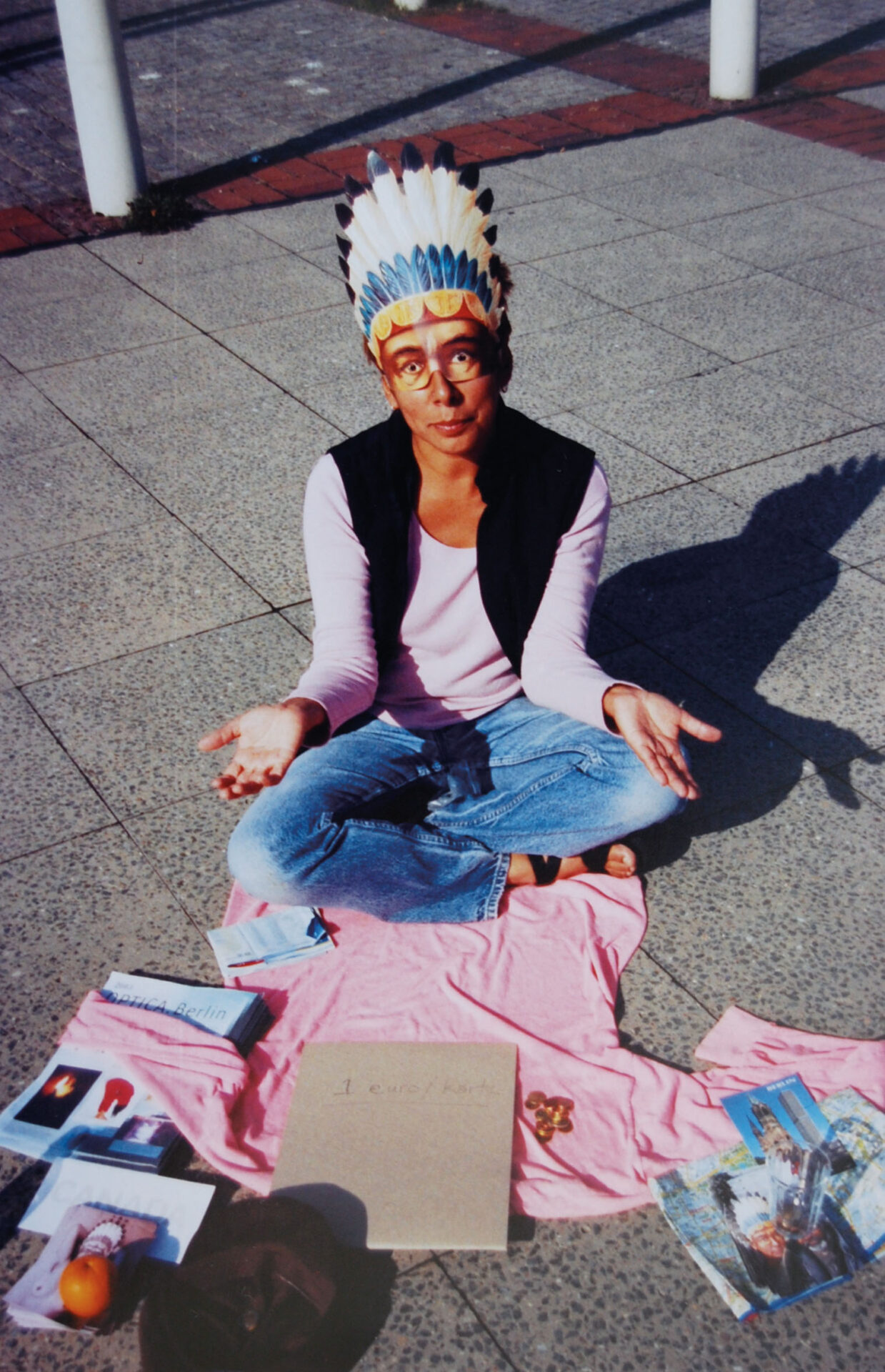

In the same spirit, Belmore created a performance for Illuminations,12 12 - OPTICA presented three commissions which were shown in rotation inside the stand: Illuminations (September 30–October 1, 2003) under the direction of Marie Fraser and Marie-Josée Lafortune with Mathieu Beauséjour, Rebecca Belmore, and Daniel Olson; Exhilaration and Dysphoria (October 2–3, 2003) under the direction of Annie Martin with Karma Clarke-Davis, Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay, and Barbara Prokop; Licht (October 4–5, 2003) under the direction of François Dion with David Altmejd, Pitseolak Ashoona, and Mindy Yan Miller. one of three commissions by OPTICA, presented during Art Forum Berlin. Sitting with crossed legs at the foot of a mat — above which hung the Canadian flag in a row of standards of the countries gathered for the event — Belmore solicited the attention of passersby with two postcards. The first, sepia in colour, was a nude portrait of herself, her hands raised behind her head, her breasts bared; on the back was written Brava!. Despite the casualness of the pose, one cannot help thinking of the photographic portraits of Edward Curtis, who played a role in perpetuating a romantic, colonial vision of Western Canada’s Amerindians in the last century. On the second card, Sun & I, the artist is photographed next to a roving immigrant of Turkish or Pakistani origin, whom she had come across while she was researching locations. On the two images, Belmore is sporting an Indian mask identical to the one she was wearing during her performance: she called out at random to passersby, asking them to buy one of the cards. Depending on their choice, she either kept the money for herself (Brava!) or donated it to the homeless (Sun & I).

On the exterior site, the reactions were immediate. Even though the visitors to the fair were “initiated,” the most engaged connoisseurs of art forms since Fluxus, many of them shunned her, clearly disapproving of an initiative they did not perceive as a performance, as a legitimate artistic gesture. The boldest among them accused her of begging, seeing her as someone repudiated by the institutions that support artists and whose career development is furthered by the fairs. The act of begging was also symptomatic of an economy that was having trouble recovering following the fall of the wall and the reunification of Germany. Finding herself suddenly invisible in the eyes of others, Belmore commemorated in silence her status as a second-class citizen, a bodily experience reinvested in the domain of (relational) art.

When all is said and done, Nicolas Bourriaud has let much ink flow across the page since the publication of Relational Aesthetics. He has managed, among other achievements, to bring together certain presuppositions, validating and expressing them in such a way that the extent and wealth of critique today bears witness to the fevered debates that he has raised: the initial debates, both circumspect and virulent, followed by others that have attempted to qualify an aesthetic that may well have influenced many an artist but has perhaps not quite fully attained the political objectives it set out to achieve.

[Translated from the French by Louise Ashcroft]