In the Canadian documentary Reel Injun (2009), Innu filmmaker André Dudemaine states, “I think that the cinema was created to film First Nations.”1 1 - André Dudemaine, quoted in Neil Diamond, Reel Injun. On the trail of the Hollywood Indian. Montréal, Canada: National Film Board of Canada, 2009. DVD, 86 min. What could be taken for a quip is, from a historical point of view, perfectly accurate. In September 1894, using a kinetograph, W.K.L. Dickson made Sioux Ghost Dance, Buffalo Dance, and Indian War Council — the very first films in the history of cinema — featuring Sioux Lakotas; in 1914, photographer Edward S. Curtis directed the first fiction feature film, In the Land of the Head Hunters, a sixty-five-minute cinematographic panorama with a plot involving the Kwakwaka’wakw before the first contact; in 1922, Robert Flaherty made Nanook of the North, the first movie documentary, a reconstruction of the life of an Inuk and his family in the Hudson Bay region. What these films from the early years of cinema show is that Aboriginals were not simply a subject of predilection for spectacles; they also generated their own form of spectacularization. Far from being a novelty, this fact dates from the first voyages of Christopher Columbus, who took Arawaks from the Bahamas back to Europe to present them at the Court of Spain. In the sixteenth century, Aboriginals were also exhibited in Europe in parades, processions, and tableaux vivants.2 2 - Nanette Jacomijn Snoep, “Des Amérindiens, premiers ‘sauvages exhibés’, aux collections de ‘monstres,’” in Exhibitions. L’invention du sauvage, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Beaux Arts éditions, 2011), 10 – 14. Spectacularization of Aboriginals only intensified with the forms of mass dissemination that were introduced during the nineteenth century in the United States and Europe, the two best examples of which were George Catlin’s Indian Gallery and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Photo : walter willems, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Many contemporary Aboriginal artists are ascribing increasing significance to the historical spectacularization of the Indian in order to lift the veil on what took place behind the scenes: large-scale spectacles (world fairs and colonial expositions, parades, circuses, early films, and so on) were being staged at the very time when extremely repressive assimilation and disappropriation policies were being instituted (the Indian Removal Act and the Indian Appropriation Act in the United States; the Indian Act in Canada). Thus, what was being put on display far and wide was precisely what was simultaneously being systematically wiped out using every means possible.

Miss chief and the showmen

The multidisciplinary work of Cree artist Kent Monkman revisits in detail the visual productions of nineteenth-century colonial culture. His strategy consists of inverting the relations of domination between the colonized and the colonizers. This righting of wrongs, if we can call it that, is conveyed through a totally anachronistic spectacular figure, Miss Chief Eagle Testikle, the artist’s flamboyant alter ego. This character is directly inspired by American pop star Cher, who, when she released her 1973 hit Half Breed — in which she evoked her Cherokee roots — appeared, mounted on a white horse, in a psychedelic Indian princess costume. Although Miss Chief has appropriated Cher’s spectacular rhinestones-and-glitter persona, her role cannot be reduced to that of a post-Indian diva; she is also a trickster,3 3 - On the figure of the trickster, see Jean-Philippe Uzel, “Trickster Objects in Contemporary Art,” in The Undecidable: Gaps and Displacements of Contemporary Art, ed. Thérèse St-Gelais, trans. Ron Ross(Montréal: Les éditions esse, 2008), 179 – 90. who enjoys overturning nineteenth-century codes of visual culture and makes fun of its underlying myth of the “vanishing Indian” — the widespread belief at the turn of the twentieth century that Aboriginals were doomed to rapid extinction as modern civilization advanced, and that it was therefore urgent to preserve the traces of their existence.

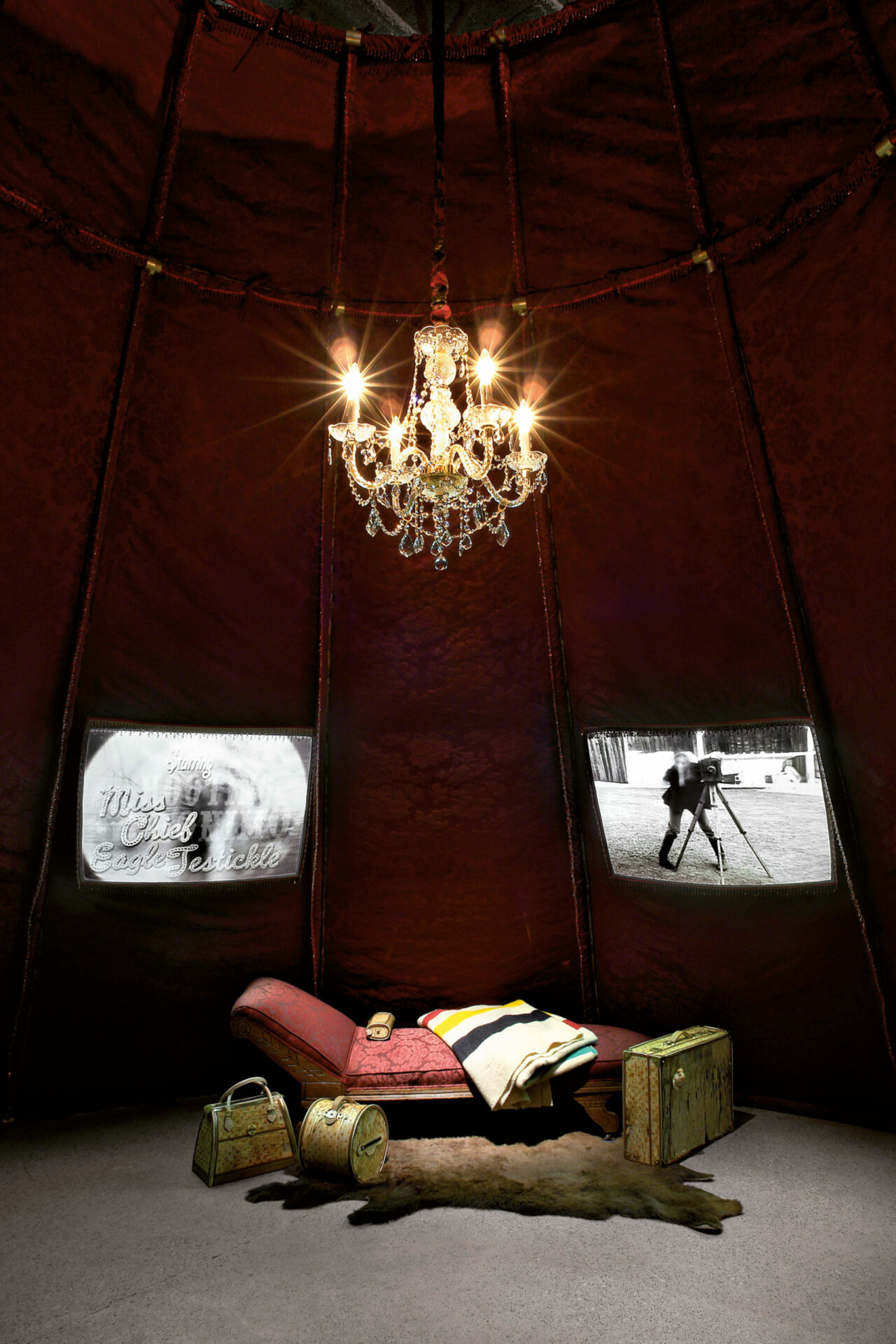

The installation Boudoir de Berdashe (2007), presented for the first time in the pan-Canadian exhibition The Triumph of Mischief, is a perfect example of Monkman’s parodic work. It consists of a luxurious tepee made of glossy fabric, within which are a chaise longue, an animal skin used as a bedside rug, and a large glass chandelier. Around the chaise longue lie Miss Chief’s personal effects: a Hudson’s Bay Company blanket, travel items made of bark, and a leather quiver stamped with the French luxury brand Louis Vuitton. This is an obvious nod to the large Crow tepee exhibited in the Indian Gallery created by American painter George Catlin. In 1839, after spending a decade painting and drawing the Plains Indians, Catlin moved to Europe, where he spent the next thirty-two years responding to the curiosity expressed by the public, including artists (Delacroix and Baudelaire, for instance) and royalty (including Queen Victoria and King Louis-Philippe). His Indian Gallery, which first presented Aboriginal artefacts (clothing, weapons, and other items) and paintings that he had made during his stay in the plains, was a dazzling success when he adopted the formula already tested by P. T. Barnum for his American Museum in New York: that of “Living Paintings of Redskins” in which groups of Ojibways and Iowas simulated war dances, scalping scenes, and attacks that anticipated Buffalo Bill’s shows by several decades.

Also in Boudoir de Berdashe was a video called Shooting Geronimo (2007), Monkman’s version of a silent western, in which a libidinous director, by the barely coded name of Frederick Curtis, directs scenes involving two scantily clad young Aboriginal men. Because Miss Chief keeps making untimely appearances behind the camera, nothing goes as planned and an actor ends up being inadvertently killed. In fact, Shooting Geronimo offers a burlesque yet subtle rereading of Edward Curtis’s In the Land of the Head Hunters, in which attraction and incomprehension, reconstruction and disappearance, fiction and science are totally intertwined.

Photos : permission de L’artiste | courtesy of the artist

photo : permission des artistes | courtesy of the artists

Remembering the victims of the spectacle

The Wild West Show produced by William F. Cody, alias Buffalo Bill, premiered in the United States in 1883 and toured Europe until 1913; it can be considered the biggest mass spectacle of the nineteenth century, as it was seen by almost 50 million people.4 4 - At the 1892 Chicago World Fair alone, a total of 6 million people — 22,000 per performance — saw the show; see Paul Reddin, Wild West Shows (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 118. The show featured scenes of Indians that blithely mixed fiction and historical reconstruction. Cody, who had himself taken part in the first Indian wars (1878 – 90), had managed to persuade well-known figures, such as Sioux chief Sitting Bull (his real name was Tatanka Yotanka) and Gabriel Dumont (one of the leaders, with Louis Riel, of the 1885 Métis Uprising) to play themselves in his shows. Cody saw no problem with these historical leaders standing alongside fictional characters such as Natty Bumppo, the hero of James Fenimore Cooper’s series of novels called Leatherstocking Tales. Nor did he have any misgivings about the fact that the “Redskins of all tribes (Cheyennes, Arapahos, Blackfoot, Sioux),” as the promotional programs for his shows announced, were in reality all Sioux Lakotas,5 5 - L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of the American Indians, 1883 – 1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999), 170. an outrageous simplification later perpetuated in Hollywood westerns, in which Indians were always Sioux. In recent years, contemporary artists have set out to remind us that behind the stereotypical images of the Indian conveyed by Cody’s shows were men and women, most of whom fell ill and died during the troupe’s European tours. For instance, in 2007, Edgar Heap of Birds (Cheyenne and Arapaho) created the installation Most Serene Republics as part of the events parallel to the 52nd Venice Biennale. The work paid tribute to the Native Americans taken to Europe by Buffalo Bill and who performed in Venice in 1890. Heap of Birds installed sixteen panels along Garibaldi Street. The text on each panel started with “Honor Morte,” ended with “Rammentare,” and gave the name of one of the Aboriginals who died in Europe: Di Nastona, Di Numshim, Standing Bear, and the others. More than simply honouring the memory of these people who died far from their homeland, in naming them, Heap of Birds was returning to them a certain form of dignity — the very dignity that Buffalo Bill’s shows had stolen from them.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Robert Houle, an Anishnabe, performed a similar exercise of commemoration with the multimedia installation Paris/Ojibwa. Presented in 2010 at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, the work paid tribute to the second troupe of Anishnabes (Ojibways) brought to Paris by Catlin in 1845. Thanks to Catlin’s notes, we know the names and ages of the eleven people in this troupe, composed of family members and companions of Maungwudaus, their chief. In Paris/Ojibwa, which reproduces the setting of a royal salon, Houle pays tribute to this troupe, particularly its members who died in Europe, among them Maungwudaus’s wife and three of their children. Where the windows are located, four painted characters (a shaman, a warrior, a dancer, and a healer) turn their backs to the viewer to stare at the horizon line of a prairie. Through the “magic of art,”6 6 - Robert Houle, “A Transatlantic Return Home Through the Magic of Art,” in Robert Houle’s Paris/Ojibwa, exhibition catalogue (Art Gallery of Peterborough, 2011), 44 – 56. Houle wanted to guide these Anishnabes back to their homeland.

photos : © David Garneau, permission de | courtesy of art mûr, Montréal

And the show goes on

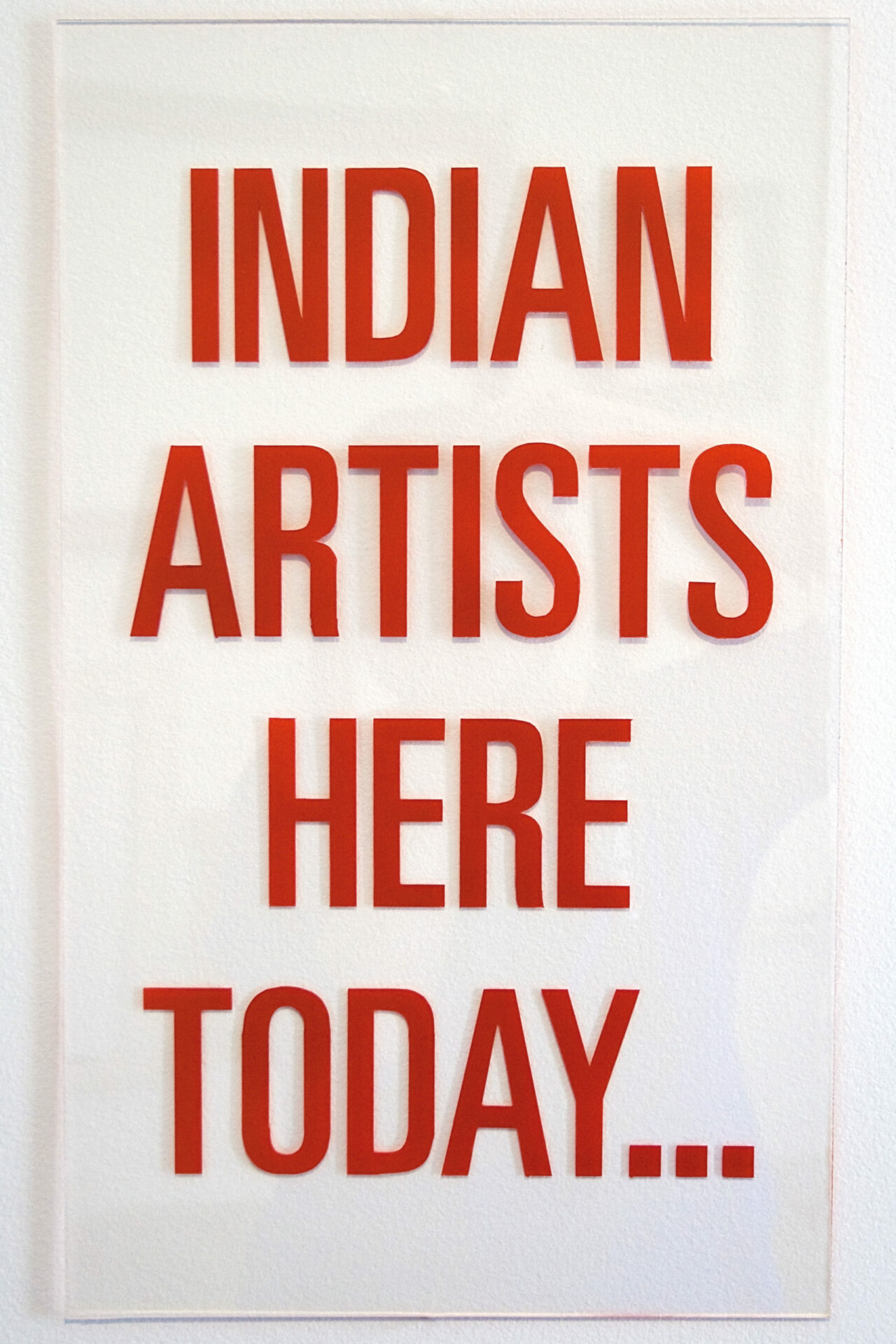

A number of Aboriginal contemporary artists continue to deconstruct the codes of the spectacular, reminding us that although the spectacle is, etymologically, “that which is offered to view,” it is also what is hidden. This was the case, for example, for the work presented in 2011 by a Gwich’in artist, Nigit’stil Norbert, at the entrance to Counting Coup, an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe. On a large Plexiglas panel, Norbert wrote, in red capital letters, “INDIAN ARTISTS HERE TODAY,” taking up the advertising rhetoric of fairground shows, as if to remind us that our relationship with Aboriginal art today is difficult to separate from the phenomenon of spectacularization created in the nineteenth century. Recently, Métis artist David Garneau produced a video titled Hoop Dancers (2013), which was shown at the Art Souterrain event in Montréal in 2014. The silent video begins with slow-motion close-ups of four First Nations dancers, dressed in their powwow costumes and seeming to perform a ceremonial dance; the long shot reveals, however, that they are in fact playing basketball. This gap between preconception and reality is also evident in the photographic Urban Indian Series (2004) by Blackfoot artist Terrance Houle. The series shows him at different moments during an ordinary day: leaving his wife on the front steps of his house, in the bus, at the office, at the grocery store — all the while dressed in his traditional powwow costume, thus highlighting through absurdity the fact that the figure of the Indian is still, in the popular imagination, caught up with the spectacular and the myth of the vanishing Indian. Anyone who doubts this can consult Before They Pass Away, a beautiful book published in 2013 by British photographer Jimmy Nelson, in which members of the “last” Aboriginal communities in the world pose in their traditional attire before “disappearing.”7 7 - www.beforethey.com. I would like to thank Sophie Guignard for drawing my attention to this book. Or they can remember that Eurodisney offers twice-daily performances of the Wild West Show, in which Sitting Bull rides along beside Mickey Mouse.

[Translated from the French by Käthe Roth]

Urban indian series #3 (train); urban indian series #6 (hotwax), 2004.

photos : Jarusha brown, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist