photo : permission de | courtesy of The Estate of Marcel Broodthaers, Bruxelles & Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

The return to objects in current art practices seems an almost natural outcome of the ebbing wave of relational art. Yet the question remains as to whether objects had really disappeared from the landscape of the 1990s and early 2000s, or had we simply refused to acknowledge them? The last Québec Triennial proposed that we take a nuanced approach to the issue, by bringing emerging artists who foreground objects and materials (Jacynthe Carrier, Mathieu Latulippe, Julie Favreau) into dialogue with artists like Massimo Guerrera, who have embodied the relational art movement in Québec, yet for whom objects and know-how are no less present.1 1 - Cf. Johanne Sloan’s article in the Triennial catalogue, which analyzes the work of Valérie Blass, BGL, and Michel de Broin: Johanne Sloan, “Everyday Objects, Enigmatic Materials,” The Québec Triennial 2011: The Work Ahead of Us, (Montréal: Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, 2011), 325-335.

I would like to consider a few recent works that share many similarities in the way they approach the question of the object, particularly the question of commodity fetishism, which has been the subject of renewed interest in recent years. Commodity fetishism is certainly the most spectacular aspect of the real or assumed return to objects in the past decade, culminating in some million-dollar sales of neo-pop art pieces during the art market boom of 2006-2008. Emblematic works of the period, to recall just a few, include Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God, a skull inlaid with thousands of diamonds, which sold for 100 million dollars in 2007; Takashi Murakami’s exhibition at the MOCA in Los Angeles the same year, which presented bags the artist had designed for the Louis Vuitton luxury brand; and Guilty, the yacht that Greek-Cypriot collector Dakis Joannou commissioned Jeff Koons to decorate in 2008. The surprising thing about these productions — aside from the outrageous sums they fetch — is the forthrightness with which they transform themselves into merchandise or luxury goods. They seem in fact to have forgone any critical function, content simply with the power of fascination they hold over collectors.2 2 - I commented on this phenomenon in 2008: see Jean-Philippe Uzel, “Trickster Objects in Contemporary Art,” translated by Ron Ross, in Thérèse Saint-Gelais, ed., The Undecidable: Gaps and Displacements of Contemporary Art (Montréal: Les éditions esse, 2008), 179-190.

Surprisingly, whether directly or indirectly, these works have gained some theoretical legitimacy with authors who, in the wake of the “iconic turn” in visual studies,3 3 - For a very good overview of the subject, see Keith Moxey, “Visual Studies and the Iconic Turn,” Journal of Visual Culture, Vol. 7 (2), (Spring 2008), 131-146. have recently become interested in the presence of images and objects and their effects on the spectator. Such an author is W.J.T. Mitchell, who, in What Do Pictures Want? (2005), radically questions critical approaches to the image and directs his interest towards how images live, how they desire. At the start of his second chapter, devoted to objects, Mitchell evaluates the work of Jeff Koons and Allan McCollum in light of Marx’s famous passage on the “fetishism of commodities.” We recall that in this text, written after visiting the first World’s Fair in London, in 1851, the author of Das Kapital is amazed at the “enigmatic character” of commodities, in which he sees “a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” He remarks that an ordinary object of everyday use, like a wooden table, “so soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than ‘table-turning’ ever was.”4 4 - Karl Marx, “The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof,” in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. I, translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling, edited by Frederick Engels [1887] (marxist.org: Marx/Engles Internet Archive, 1995, 1999), Section 4 of Chapter One, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch01.htm. One might say that all of Marx’s work consists in deconstructing this mysterious power of commodities by demonstrating that behind the fetish lies the iron law of capitalism and the logic of exploitation. And one might suppose that Marx engaged in this demystification with all the more conviction for having himself experienced the enchantment of the merchandise at the World’s Fair. Whatever the case may be, his iconoclasm marked the social sciences throughout the twentieth century, right up to the sociological criticism of Pierre Bourdieu, ever wary of fetishes, especially the fetishes of art.5 5 - He thus declared “Warhol’s Brillo boxes and Klein’s monochromes owe their value and their formal properties solely to the structure of the field.” Pierre Bourdieu, “Genèse historique d’une esthétique pure,” Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, No. 27 (Spring 1989), 104 (Our translation).

photo : © Zoe Leonard, permission de |

courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Yet Mitchell’s take on the “fetish character of the commodity” in Marx’s work is particular for its rather literal reading, free of iconoclasm. He readily admits to his fascination for objects — fetishes, totems, idols — that lead a life of their own and manage to impose their desires on dazzled spectators. One must understand that this has very little to do with the ideas Bruno Latour has been developing over the last twenty years, by which “quasi-objects” — “mixtures” of subjects and things — have continued to proliferate within modernity, which refused to see them.6 6 - Bruno Latour, Sur le culte moderne des dieux faitiches (Paris: La Découverte, 2009). Indeed, with Mitchell it isn’t a matter of a hybrid logic of subject and object, but of a monumental reversal by which objects become subjects and subjects become objects. According to Mitchell, objects, starting with art objects, come to life and imperiously demand that subjects act in a particular way: “Totems, fetishes, and idols are, finally, things that want things, that demand, desire, even require things — food, money, blood, respect. It goes without saying that they have ‘lives of their own’ as animated, vital objects. What do they want from us? [….] Fetishes, as I’ve suggested, characteristically want to be beheld — to ‘be held’ close by, or even reattached to, the body of the fetishist.”7 7 - W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 194. But what Mitchell does not say here is that he himself is foremost among fetishists, taking us from Marx’s radical iconoclasm to his own radical fetishism.

And yet many current art practices, even if less conspicuous than neo-pop artworks, raise the question of fetishism in less Manichean terms, in part because they make the fetish coexist with its critique. Such is particularly the case with works that use precious materials (gold, silver, diamonds) or bank notes, precisely because these “objects” are animated by a commercial value that never completely dissipates in their artistic value. They are literally animated by a soul (anima in Latin) that resists all subversions and even their own destruction.

photo : Étienne Boucher, permission de |

courtesy of the artists & Art Mûr, Montréal

The first example I would like to discuss is Le petit gâteau d’or (2010), an installation by Québec duo Cooke-Sasseville that was presented in the exhibition of the same name at Art Mûr gallery in Montréal in the spring of 2010. At the heart of the exhibition was a little cupcake made of precious materials, for which the artists themselves provided the recipe: “To make a little golden cupcake you need: 117g of 18-carat gold, 104g of 925 silver, 13 diamonds, 4 emeralds, 3 rhodolite garnets, 3 rubies, 4 topazes, 3 amethysts, 4 sapphires.”8 8 - www.cooke-sasseville.net/lepetitgateau.htm The work obviously alluded, at much reduced scale, to Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God, presented at London’s White Cube in 2007. However, there is a significant difference between the fetishes of Hirst and Cooke-Sasseville: the inaccessible nature of Hirst’s fetish object was spectacularly manifest in the exhibition context (dramatic lighting, drastic security measures, etc.), whereas the latter work mocked the former, without eclipsing its power by any means. Indeed, on entering the “Petit gâteau d’or” exhibition, visitors first had to cross a room where ten or so lithographs were on display (Valeur refuge — safe investment — 2010), representing gold ingots in various nibbled states. Directing visitors from one room to the other was a red carpet that suggested a natural transition between the repast of gold and the presence of the little cake.9 9 - Cf. Marie-Ève Charron’s analysis comparing Le petit gâteau with Piero Manzoni’s Merde d’artiste (1961): Marie-Ève Charron, “Cooke-Sasseville’s Golden Recipe,” translated by Eduardo Ralickas, esse, no. 69 (Bling-bling) (Spring-Summer 2010), 32-36. Commodity fetishism is here defused by its psychological equivalent: unwarranted lust for money — or any precious object — which in Freud’s terms is synonymous with libidinal regression to an anal phase. By showing that a fetish is nothing without the context that enables its existence, Le petit gâteau recalled Marcel Broodthaers’ Lingot d’or (1970-1971), an ingot sold for twice the value of its weight in gold thanks to the transubstantiating effects of the museum, here the “Section financière” of the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, the museum founded by the Belgian artist in 1968.

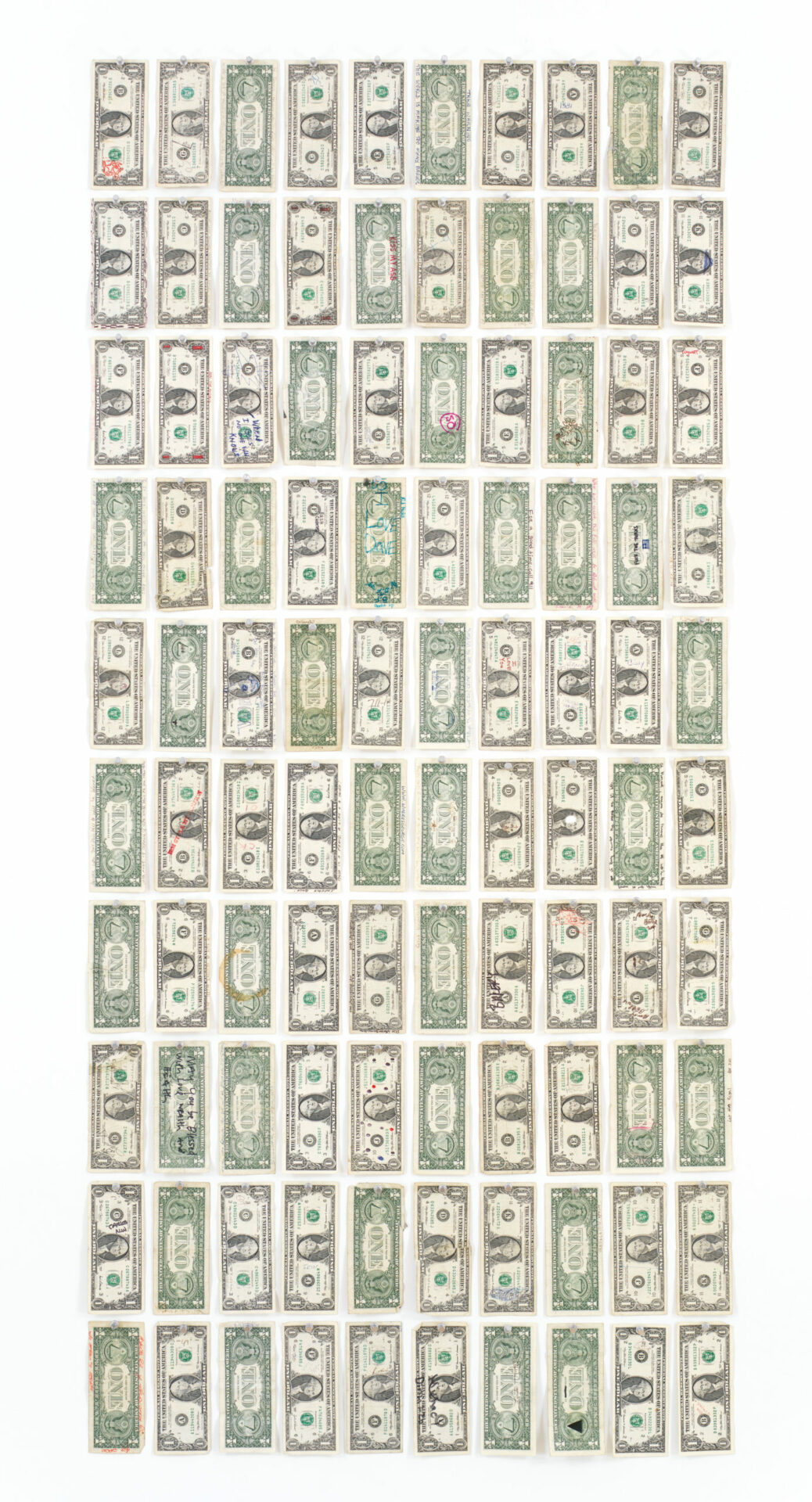

Other contemporary works demonstrate the fetishistic power of commercial objects by working directly with bank notes, for money, as Marx so keenly observed, is the absolute object of bourgeois society: “By possessing the property of buying everything, by possessing the property of appropriating all objects, money is thus the object of eminent possession.”10 10 - Karl Marx, Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, translated by Martin Mulligan (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1959), “The Power of Money,” in the Third Manuscript, consulted online at www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/power.htm. Such is the case, for instance, with American artist Zoe Leonard’s One Hundred Dollars (2000-2008), which consists of a hundred American one dollar bills pinned side by side in ten columns and ten rows to form a rectangle. Visually, the work instantly conjures up Andy Warhol’s 1962 One Dollar Bills series, yet here it isn’t a matter of turning money into an icon of consumer society, but of putting its exchange value on hold to give free rein to its use value. Each of the hundred bills bears an anonymous inscription (a name, phone number, shopping list, website, political message, prayer, warning, joke) or a drawing, scrawl, coffee cup stain, piece of adhesive tape, reminding us that a bank note is also a material object that preserves traces of the many uses it is subjected to every day. The work isn’t meant to denounce or praise the fetishist power of money, in which Marx saw “the confounding and confusing of all natural and human qualities,”11 11 - Ibid. but to show that beyond this, money also possesses a use value that gives it a human dimension.

Cildo Meireles, Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos: Projeto Cédula [Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Banknotes Project], 1970.

photo : © Cildo Meireles, permission de | courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York

photo : permission de l’artiste |

courtesy of the artist

The bank note alterations are not always anonymous; they may also be the outcome of the artist’s intervention, as in the case of Québec artist Mathieu Beauséjour’s Survival Virus de Survie (1991-1999), in which the artist used an ink stamp to obliterate more than 100,000 dollar bills, meticulously taking down their serial numbers as he went along. Critical response emphasized the project’s subversive dimension, its borderline legality. But one can’t help notice the fact that Beauséjour’s approach is more than just critical; whereas Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles, in Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos (1970), printed such phrases as “Yankees go home” on bank notes that he then recirculated, Survival Virus de Survie does not merely use the bank notes as a medium for disseminating a political message: it also reveals the quasi magical quality of money, the supernatural power by which a mere piece of paper can transform the world and throw human relationships into turmoil. This fetishistic aspect of money is not revoked in Beauséjour’s work, but exposed by its negative. Economist Ianick Marcil observed as much in his commentary on Beauséjour’s Filth (2007), in which the artist exhibited thousands of shredded bills in an abandoned bank vault: “As if […] contemplating the thousands of shredded dollars, now valueless in the commercial system, one sought its vanished soul through its negative.”12 12 - Ianick Marcil, “Futilité, art et argent,” Mathieu Beauséjour. Persistance, exhibition catalogue (Montréal: Quartier éphémère, 2007), 117. Where Leonard set aside the exchange value of money in order to show its use value, Beauséjour reveals money’s soul through its very destruction.

These works by Cooke-Sasseville, Leonard, and Beauséjour highlight the way objects operate in current artistic practice. They are not merely striving to give life to objects, as Mitchell suggests, but are also attempting to animate them — to give them a soul — and to deconstruct their power of fascination. To make the tables dance on their heads and, at the same time, reveal the man directing from the shadows.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]