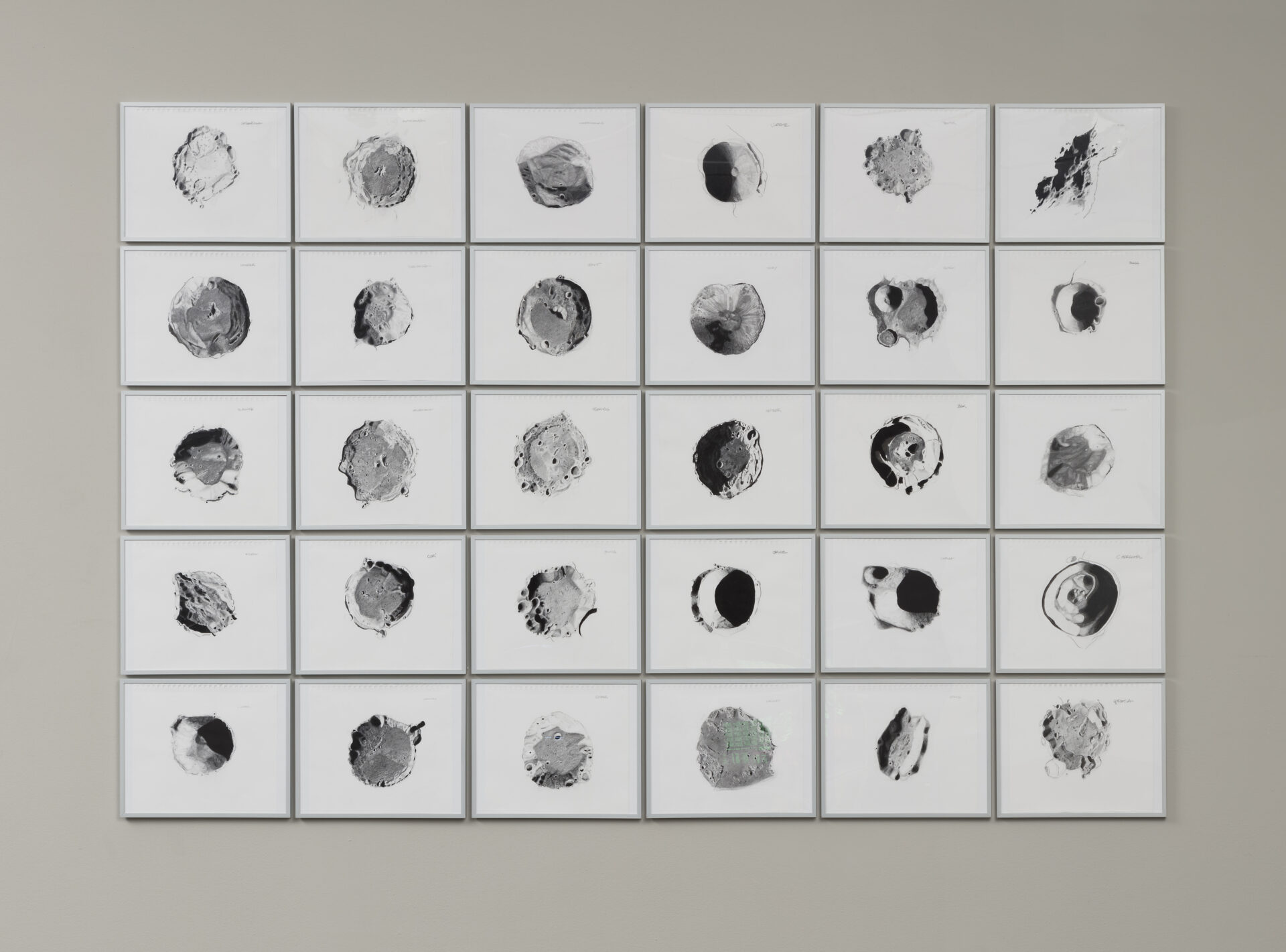

The Encyclopedic Palace

June 1 – November 24, 2013

photo : courtesy of the artist and kamel mennour, Paris

June 1 – November 24, 2013

Italian curator Massimiliano Gioni has staged a massive project premised on failure as the main exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale. Taking its name from self-taught artist Marino Auriti’s abandoned attempt to design a museum to house all the world’s knowledge, The Encyclopedic Palaceannounced its two main themes from the outset: an interest in the production of non-artists, eccentrics, and hobbyists; and an insistence on the impossibility of encapsulating the world’s cultural production in one place. But Gioni’s show never strays into disaffectation. Instead, it is marked by an enthusiasm for the eccentricities that motivate the impulse to catalogue, evinced most powerfully by Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013), a single channel video that uses pop-up browser windows and a hip hop soundtrack (the lyrics mash up the Old Testament with New Age spirituality) to create a collage of some of the thousands of objects stored at the Smithsonian Institute.

Much like Henrot’s video, The Encyclopedic Palace is an exhibition of texts as much as images, with more than one hundred thousand words appearing in the show. But while traditional didactic panels often stifle a curator’s intuitive placement of works, these artists’ texts operate differently, allowing the viewer to draw nuanced connections between the exhibition’s rooms while effortlessly unpacking each artist’s practice. In one particularly striking pairing, a series of anatomically perfect models of surly teenaged girls, created by Morton Bartlett over thirty years and undiscovered until his death, leads directly to Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s sprawling Suddenly this Overview (1981 — 2012), a collection of two hundred unfired clay sculptures clumsily monumentalizing different objects, concepts, and events from human history. Seen together, the works highlight a recurring tension between a painstaking attention to detail and amateurish enthusiasm.

One of the show’s only flaws is that it sometimes suggests only “crazy people” (marginalized figures, “outsider” artists, or those declared criminally insane) would earnestly try to reinvent the world in miniature form, while artists have the critical distance to make the same gesture with an attitude of knowing performativity and self-deprecating irony. There are moments, however, when the distinction between these two positions breaks down, as it does with Sleep Study, a series of tiny and impossibly beautiful porcelain sculptures by seventy-year-old artist Ron Nagle that evoke extraterrestrial forms and primal dreamscapes. Sketched by the artist each night while watching Charlie Chan movies before he goes to sleep, these intricate scenes in rich hues flecked with gold suggest a sincere determination to create alternative worlds that only seem possible in the routine act of watching television in bed. It is in these moments that The Encyclopedic Palace is at its best, celebrating the kinds of worlds that can be dreamt up in the banal space of the everyday.