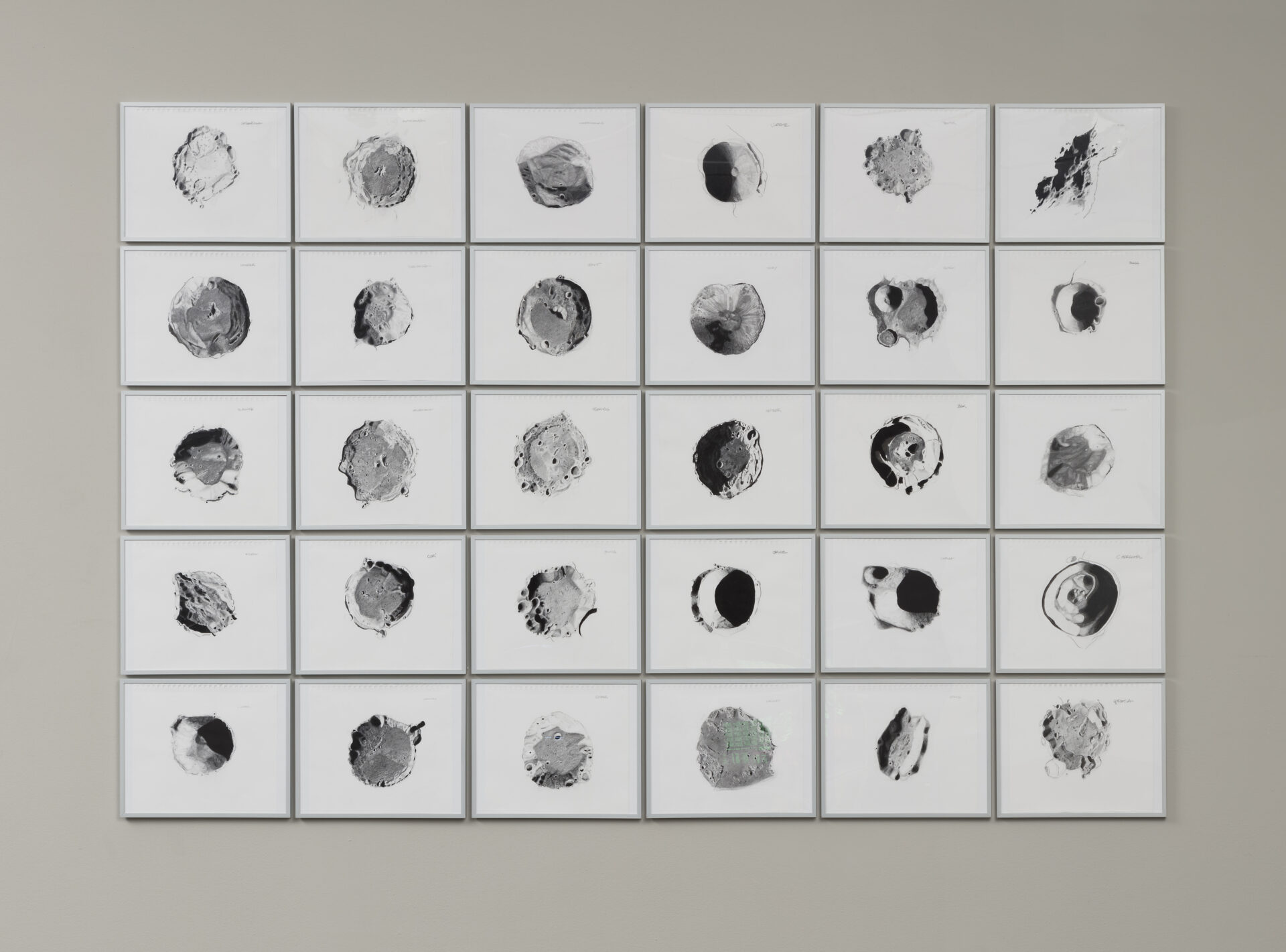

Photo : Michael Barrick, courtesty of the artist & Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver

October 8–December 5, 2010

Mark Boulos tests the possibilities for documenting what is not visual. During a recent exhibition at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, the American artist presented three video installations focusing on the manifestation of religious, political, and economic ideologies.

In the single-channel video projection, The Word Was God (2007), the religious beliefs of two Christian communities are expressed through language. The Shiloh Pentecostal Church members pray until they speak in tongues; their collective volume contrasts sharply with the quiet of a man living alone in the Syrian desert (a contrast unfortunately lost when sound from the next video spills into the room). This man speaks Aramaic, the language that Jesus spoke, while the Pentecostalists believe that only God can understand their tongues. Boulos subtly extends this consideration of language to include physical expressions when he highlights the Pentecostalists rocking, lying in pews, and spontaneously clapping.

In All That is Solid Melts Into Air (2008), belief manifests in militant action. The installation is physically impressive: two videos are projected on eighteen-foot screens that face each other. One video is of the MEND guerrilla group fighting the oil industry in the Niger Delta, and the other is of Chicago’s Mercantile Exchange, where oil is traded. As the title suggests, the piece elegantly inverts expectations about materiality and metaphysics. The MEND members have a clear understanding of the corporate and governmental forces controlling their immediate material reality; they also believe that a spirit makes them impenetrable to bullets. Conversely, the Chicago traders revere futures and derivatives: financial products that are intangible yet contributed to the 2008 economic (and for many, material) crisis.

The final piece, No Permanent Address (2010), portrays the New People’s Army, the military faction of the Communist Party of the Philippines. Through sixteen colour portraits and a three-channel video installation, Boulos traces relationships between individuals and the collective, and reminds us of the power of a single person. Boulos’ own relationship to the whole is notable: he travels without a crew, putting himself in considerable danger to temporarily join these communities.

Boulos’ background in both philosophy and documentary filmmaking is evident in his questioning of the documentary genre. His videos are documentary in that unscripted events are recorded as they unfold, but they are greatly shaped through editing (Boulos’ “process of subtraction” results in fragments rather than a comprehensive overview). This questioning is extended in the film series, discussions, and artist’s talk that accompany the show. As in his videos, Boulos expresses his questions and beliefs with refreshing sincerity. It is appropriate that Boulos uses video installation to depict metaphysical beliefs and their material effects. These seductive installations immerse the viewer in bright colours, textures, sounds, and movement: powerfully invoking the “spell of cinema.”