Interview with Nicole Gingras

International Festival of Films on Art, Montréal & Québec

March 14 to 26, 2023 (in theatres)

March 26 to April 22, 2023 (online)

March 14 to 26, 2023 (in theatres)

March 26 to April 22, 2023 (online)

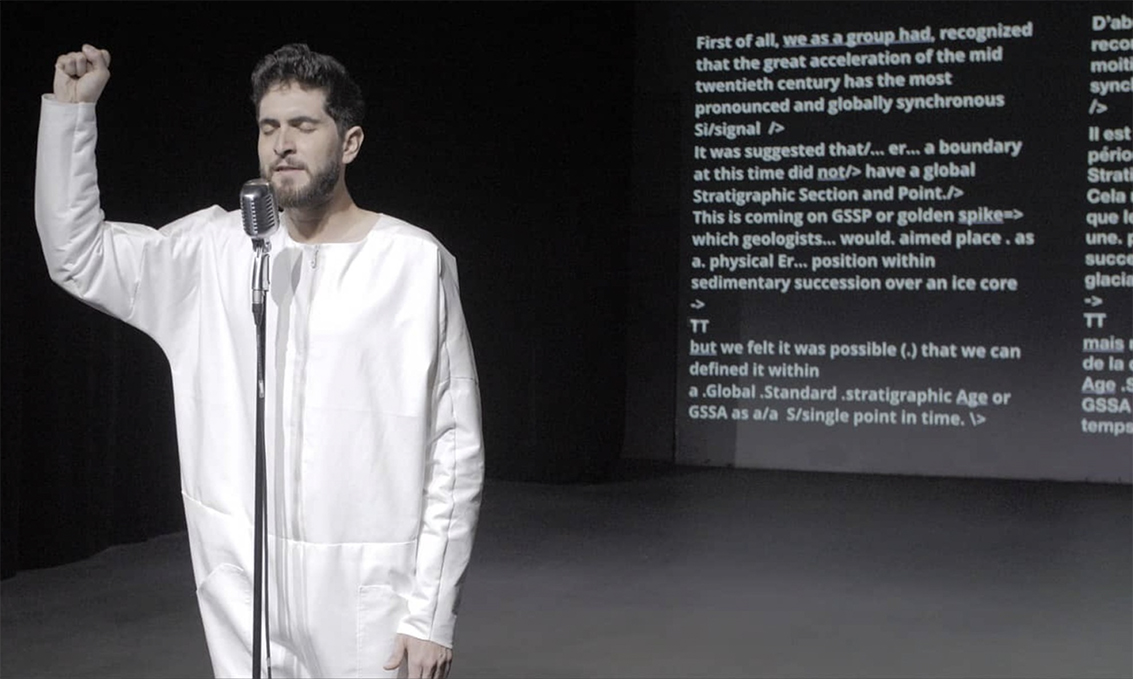

Expression, centre d'exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe, 2019.

Photo: Paul Litherland, courtesy of Expression,

centre d'exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe

International Festival of Films on Art, Montréal & Québec

March 14 to 26, 2023 (in theatres)

March 26 to April 22, 2023 (online)

March 14 to 26, 2023 (in theatres)

March 26 to April 22, 2023 (online)

With the sensitive and detailed eye that characterizes her curatorial practice, curator Nicole Gingras has been organizing the programming for the FIFA Experimental section of the International Festival of Films on Art (Le FIFA) for more than twenty years as of the current edition. Over this time, she has presented countless works by image-in-movement artists. In collaboration with Le FIFA, Esse wanted to take advantage of the opening of the festival’s 41st edition, on March 14, 2023, to publish a conversation between curators Véronique Leblanc and Nicole Gingras.

Véronique Leblanc : Your work as a curator is often associated with time-based art practices that have a time component, such as sound art, video art, and experimental film. How do the notions of time and temporality inform your approach to curating?

Create your free profile or log in now to read the full text!

My Account