Photo: Angel Tzvetanov, courtesy of

Arndt & Partner, Berlin & Zurich

Since the September 11 terrorist attacks, we have witnessed “conspiracy theories,” and their attendant extremist positions, spread throughout ever-wider fringes of public opinion.1 1 - Guillaume Dasquié and Jean Guisnel, L’effroyable mensonge, thèse et foutaises sur le 11 septembre (Paris: La Découverte, 2002). Thierry Meyssan’s book 9/11: The Big Lie is no doubt the most striking example of this new wave of conspiracy theories. According to Meyssan, the September 11 attacks were not the work of the international terrorist organization Al-Qaeda, but a coup d’État carried out by a secret group within the U.S. administration in an attempt to impose a hard line on President Bush. Proof of this conspiracy: it was not an airplane which struck the Pentagon but an American missile, as several details make clear, such as the size of the hole in the building’s exterior and the absence of debris on the lawn. This thesis spread on the Internet and then in the form of a book, which sold 300,000 copies in its French edition before being published in 27 languages around the world.

Conspiracy myths began to appear with the modern exercising of power. They are politics’ negative side, their shadow in a sense. The appearance of conspiracy thinking dates to the birth of a socio-political order which is no longer immutable and traditional but subject instead to the transformative activities of the human will. It took shape in counter-revolutionary circles soon after the French Revolution: in 1797, the Abbé Barruel interpreted those events as the product of a Masonic conspiracy.2 2 - Pierre-André Taguieff, Les Protocoles des Sages de Sion. Faux et usages d’un faux (Paris: Fayard, 1987). This rhetoric is still visible in today’s far-right wing: in this view, modernity is the result of a conspiracy and all groups who hold any sort of power, in reality or not, are liable to seeing others fantasize about their influence. These conspiracy theories are tied to history; even if new hidden powers appear (Jews, capitalists, Americans, etc.), the shape of the conspiratorial narrative remains essentially the same. This is the domain of extremists, whether from the right or the left. For several years now, various people who study such phenomena have drawn attention to this renewed fashion for conspiracy theories and alerted the public. The distress caused by globalization feeds conspiratorial interpretations: the proliferating anti-globalization (and anti-American) discourses, travelling back and forth between one extreme and the other, often take the form of conspiracy theories and are full of dangers for political thinking. This proliferation concerns those who work in the field, because conspiratorial ideas are loaded with violence: by accrediting a group with a powerful and disproportionately malign influence, they use a projection mechanism to justify passing to action. Far-right ideologies are typically conspiracy theories, with the Jewish-Masonic conspiracy being the best known because it was the model for Nazism.

In his book Crowds and Power, Elias Canetti uses the memoirs of the Austrian judge Paul Daniel Schreber to establish a parallel between the private madness of the memoirs’ author and the public madness of Adolf Hitler.3 3 - Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power, trans. Carol Stewart (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984 [1960]). The case of this judge was made famous by Sigmund Freud in his analysis of the mechanisms of the projection and “return of the repressed” typical of paranoid schizophrenia.4 4 - Sigmund Freud, “Psycho-Analytical Remarks on an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides),” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 12, ed. and trans. James Strachey, (London: Hogarth Press/Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1958), 9-82.

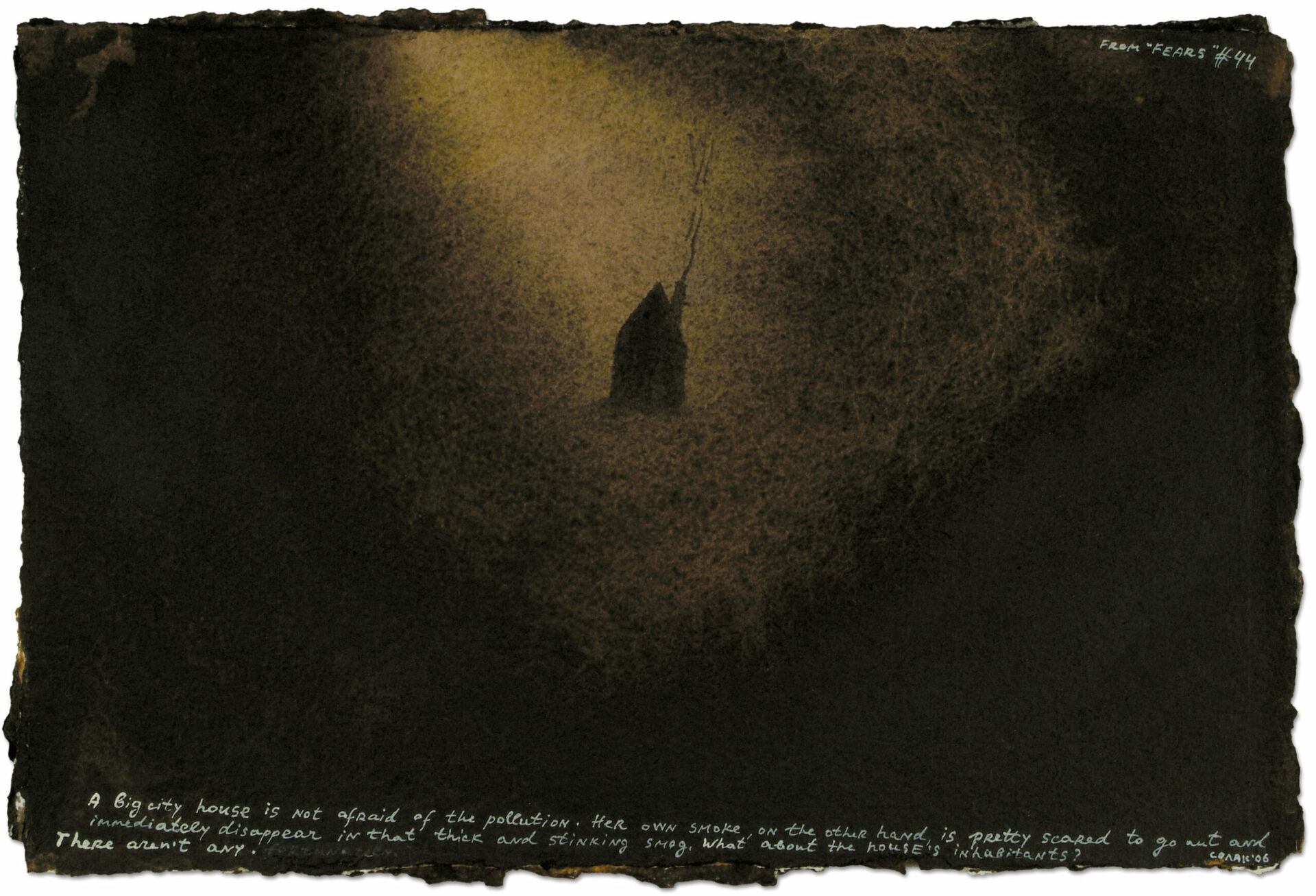

Fears #55, 2006-2007.

Photo: Angel Tzvetanov, courtesy of

Arndt & Partner, Berlin & Zurich

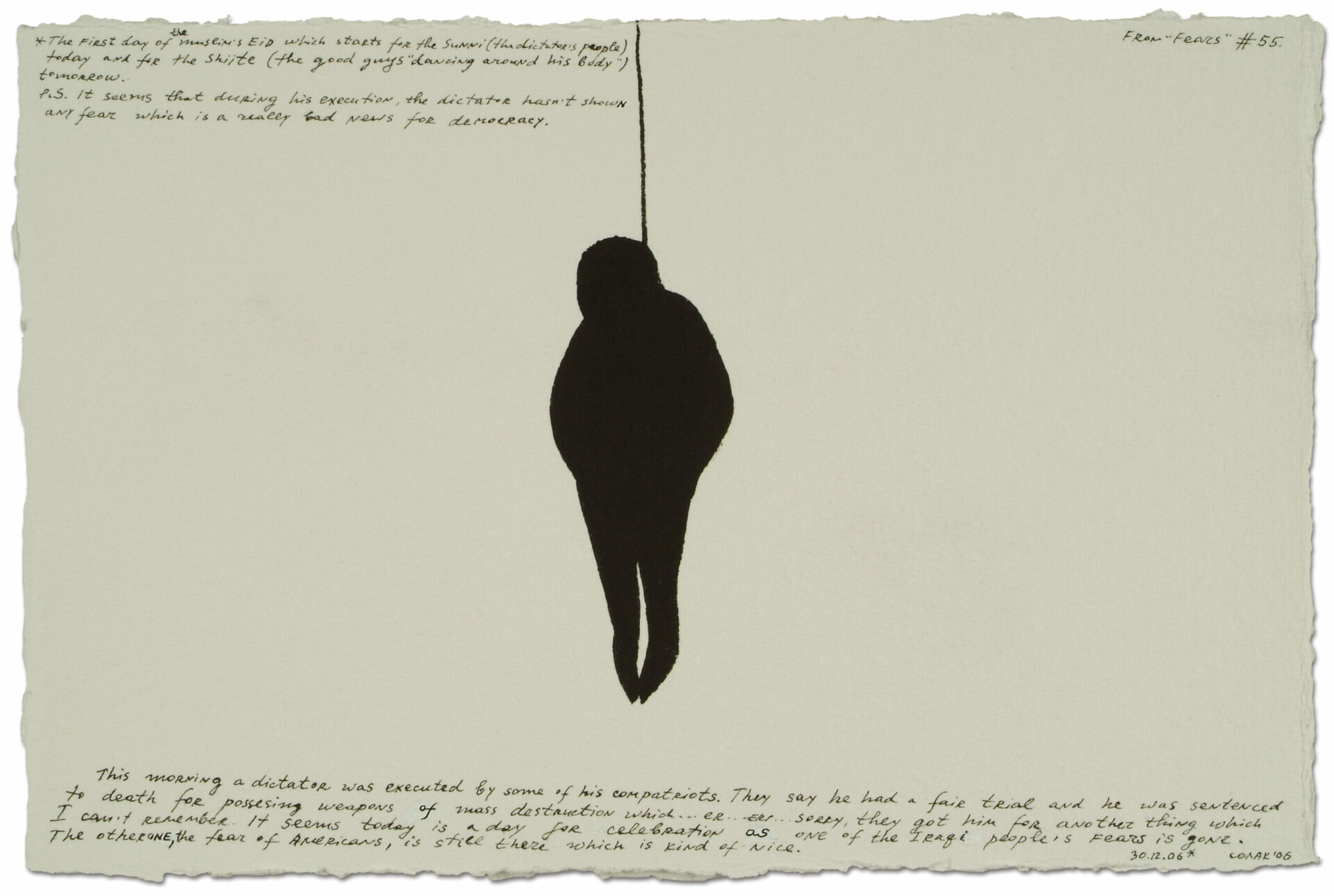

Fears #94, 2006-2007.

Photo: Angel Tzvetanov, courtesy of

Arndt & Partner, Berlin & Zurich

The psychiatric metaphor is regularly invoked to understand power in its most extreme or destructive manifestations. The personalities of dictators have made us sensitive to this reality: the fantasy of the paranoiac, when in power, becomes everyone’s reality, because the paranoiac is not only someone who fantasizes about persecution but also, when able, really persecutes in return. Paranoid delirium is reversible: those affected project their own faults onto their victims so as to punish them better.

For Canetti, all despots and sovereigns behave in a paranoid manner. Paranoid delirium is “exactly the model of political power feeding and building from the masses.” Paranoia, because it is an expression of the madness of power which inhabits all of us, is propagated in groups. Under the leadership of the despot, society as a whole enters into a delirium of persecution. It is not a matter of oppression from without, imposed on a free society, but of intrinsic paranoid tendencies which the despot makes real for us. In other words, despots feed off our fears before presenting themselves as the solution, and apparently we are stupid enough to submit to them for deliverance. Writers who describe themselves as “Schreberians” seek in the Austrian judge’s writings the roots of proto‑Nazism.

Gilles Deleuze’s and Félix Guattari’s book Anti-Oedipus, published in 1972, went a long way towards conveying the message that power was essentially paranoiac. Significantly, their ideas developed in the wake of May 1968. They saw their work as a response to the question posed by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich: how can we account for the fact that the masses wanted fascism?5 5 - Wilhelm Reich, The Mass Psychology of Fascism, trans. Theodore P. Wolfe (New York: Orgone Institute Publications, 1946). Or, to use Canetti’s terminology, how can we account for the spread of paranoia from the despot to the masses? These questions are also valid with respect to the “need for security” seen these past twenty years in Western societies, because we must acknowledge that this is not only the result of September 11 and anti-terrorist media campaigns, even if these gave the issue a degree of intensity it had never before attained.

This perversion of collective desire is what we must explore. According to Deleuze and Guattari, the desire for repression is the result of a “secondary repression.”6 6 - Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, L’Anti-Œdipe, (Paris: Minuit, 1972), 40. When the “primitive territorial machine” is no longer enough to address the disorder brought about by capitalist globalization, the “despotic machine” establishes an over-encoding: “In producing itself capitalism creates a tremendous schizophrenic charge on which it puts all the weight of repression but which continually reproduces itself as the limit of such a process.” This is why the question of repression is tied to the development of a capitalism which oscillates between the two extremes of a liberation of flows and a great, over-encoding unity which makes it possible to control them: “de-territorialization and re-territorialization,” schizophrenia and paranoia.

Paranoia is thus not only a mental pathology which affects some individuals; it is also a form of social thought fed by the uncertainty and distress of modernity. In his work on McCarthyism, the historian Richard Hofstadter identifies the principal features of this feeling of collective persecution, which he calls “paranoid style.”7 7 - Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays (New York: Random House, 1967), 4. According to the anthropologist George Marcus, the crisis in representation following the end of the Cold War contributed to the development of this paranoid style.8 8 - George E. Marcus and Michael G. Powell, “From Conspiracy Theories in the Incipient New World Order of the 1990s to Regimes of Transparency Now,” Anthropological Quarterly 76 no. 2 (2003): 323-34.

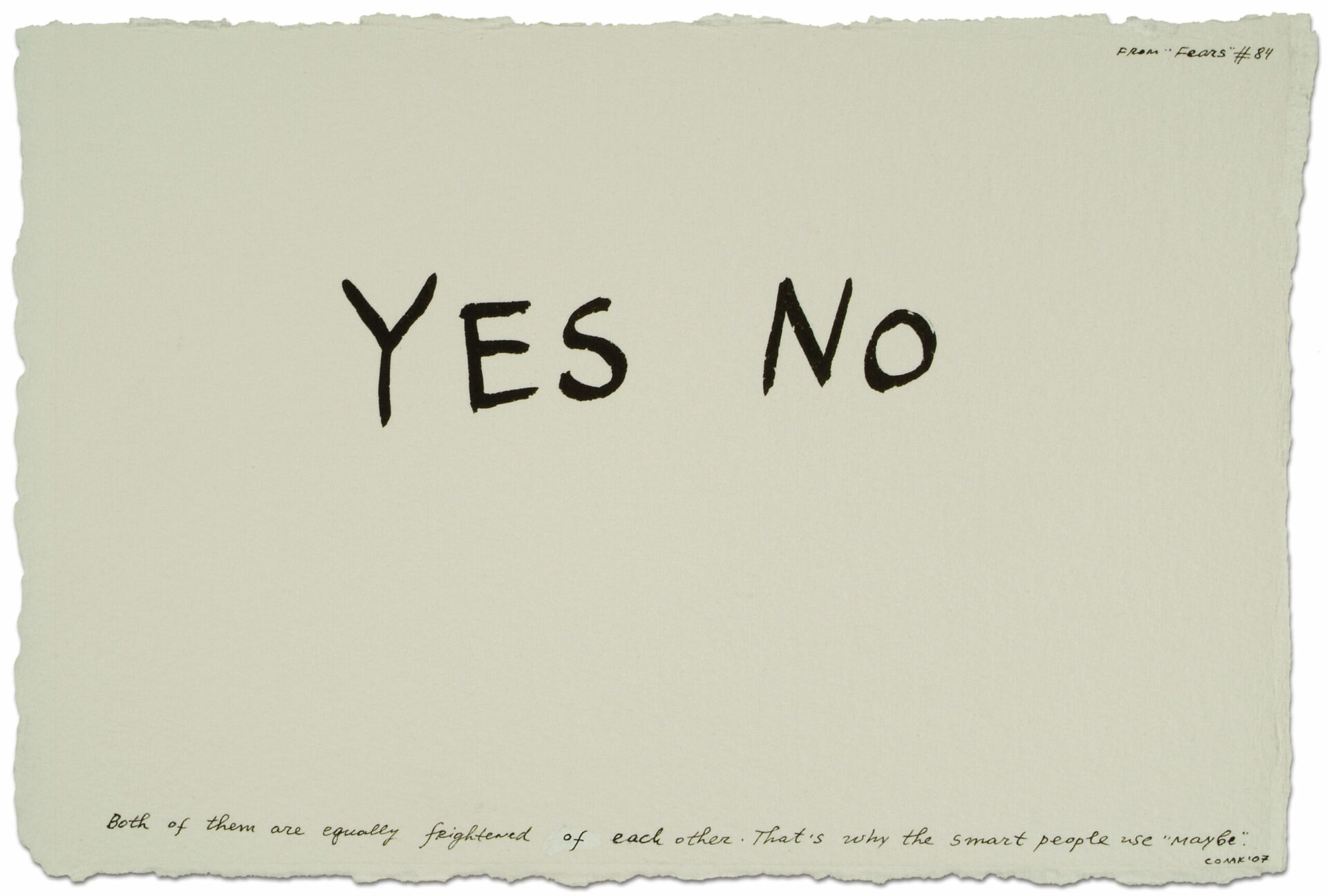

Fears #84, 2006-2007.

Photo: Angel Tzvetanov, courtesy of

Arndt & Partner, Berlin & Zurich

The desire for security is even stronger in that we have fantasized about the calling into question of global capitalism embodied by the World Trade Center towers. Significantly, the day after the attacks, we were all “Americans.” Jean Baudrillard immediately grasped the logic of this reaction: “The fact that we have dreamt of this event, that every one without exception has dreamt of it—because no one can avoid dreaming of the destruction of any power that has become hegemonic to this degree—is unacceptable to the Western moral conscience. Yet it is a fact, and one which can indeed be measured by the emotive violence of all that has been said and written in the effort to dispel it.”9 9 - Jean Baudrillard, The Sprit of Terrorism and Other Essays, trans. Chris Turner (London/New York: Verso, 2003 [2002]), 5.

Since 2001, in light of the creation of an international coalition against terrorism and of the security measures that have been put in place, we have all become, effectively, potential terrorists. This at least is what the state appears to be telling us through the surveillance systems it has put in place from one end of the world to the other to “protect” us. Six years later, in view of the results obtained, it is difficult not to think that the targets of these security measures were the democratic guarantees of our freedom and not Islamic fundamentalists, who have all too clearly obtained what they were after.

As Baudrillard remarks, “The repression of terrorism spirals around as unpredictably as the terrorist act itself. No one knows where it will stop, or what turnabouts there may yet be. . . . And it is this uncontrollable unleashing of reversibility that is terrorism’s true victory. A victory that is visible in the subterranean ramifications and infiltrations of the event—not quite in the direct economic, political, financial slump in the whole of the system—and the resulting moral and psychological downturn—but in the slump of the value system, in the whole ideology of freedom, of free circulation, and so on, on which the Western world prided itself, and on which it drew to exert its hold over the rest of the world.”10 10 - Ibid., 31-2.

Terrorists are not idiots; they know very well that their actions will unleash repression that will surpass by far their own disruptive methods, but this serves their interests, because state violence justifies their struggle after the fact and swells the ranks of their troops. The repression of terrorism only serves to meet the terrorists’ secret injunctions. What a symbolic victory for the power of Good! We are faced with a perverse act of masochism: terrorist martyrs expose the true nature of state power by leading it into a downward spiral of violence. It is inevitably counter-productive to meet violence with violence, because by embarking on the so-called “war on terror” (which is already a contradiction of terms), George W. Bush is objectively playing bin Laden’s game.

The state takes advantage of the continued presence of terrorism whenever its power and legitimacy are weakened.11 11 - Zygmunt Bauman, Le présent liquide. Peurs sociales et obsession sécuritaire (Paris: Seuil, 2007), 26. This is so apparent that some writers have developed conspiracy theories which call into question the role of certain political groups or even certain sectors of the state apparatus, such as the secret intelligence services. This is not entirely without foundation, because we know that the police and the army, at various times in various places, have been able to carry out so‑called counter-insurgency techniques. The fact is that terrorist attacks, in the end, serve the policies put in place by the authorities.

In order to thwart this conspiratorial thinking, which deals a blow to all efforts to uncover the truth, it would undoubtedly be wiser to look at the rhetorical strategies of the representatives of political authorities, because they tell us much more about the business of terror than terrorist networks themselves and imaginary plots to seize power. In the end, it doesn’t matter whether or not hidden structures capable of putting in place perverse strategies exist when political manipulations of terrorist violence are so evident. There’s no need to take up conspiracy theories when the newspapers describe another form of coercive violence, one less sensational but just as effective: social control.

Fear mongering is also part of a perverse strategy. For Pier Paolo Pasolini, the political use that the Christian Democrats made of the fear of terrorism to reinforce social control in Italy in the 1970s was a “new fascism.”12 12 - Pier Paolo Pasolini, “L’articlolo delle lucciole” (1 February 1975), Scritti corsari (N.p.: Garzanti, 1990), 128-34. Indeed politicians behave exactly like little Mafiosi when they offer to “protect” us against a danger that they themselves have helped create. Politicians aren’t necessarily interested in dissipating our fears by privileging “transparency.” On the contrary, their media campaigns help feed people’s uncertainties and paranoia. Some of them have become masters of the art of confusion.

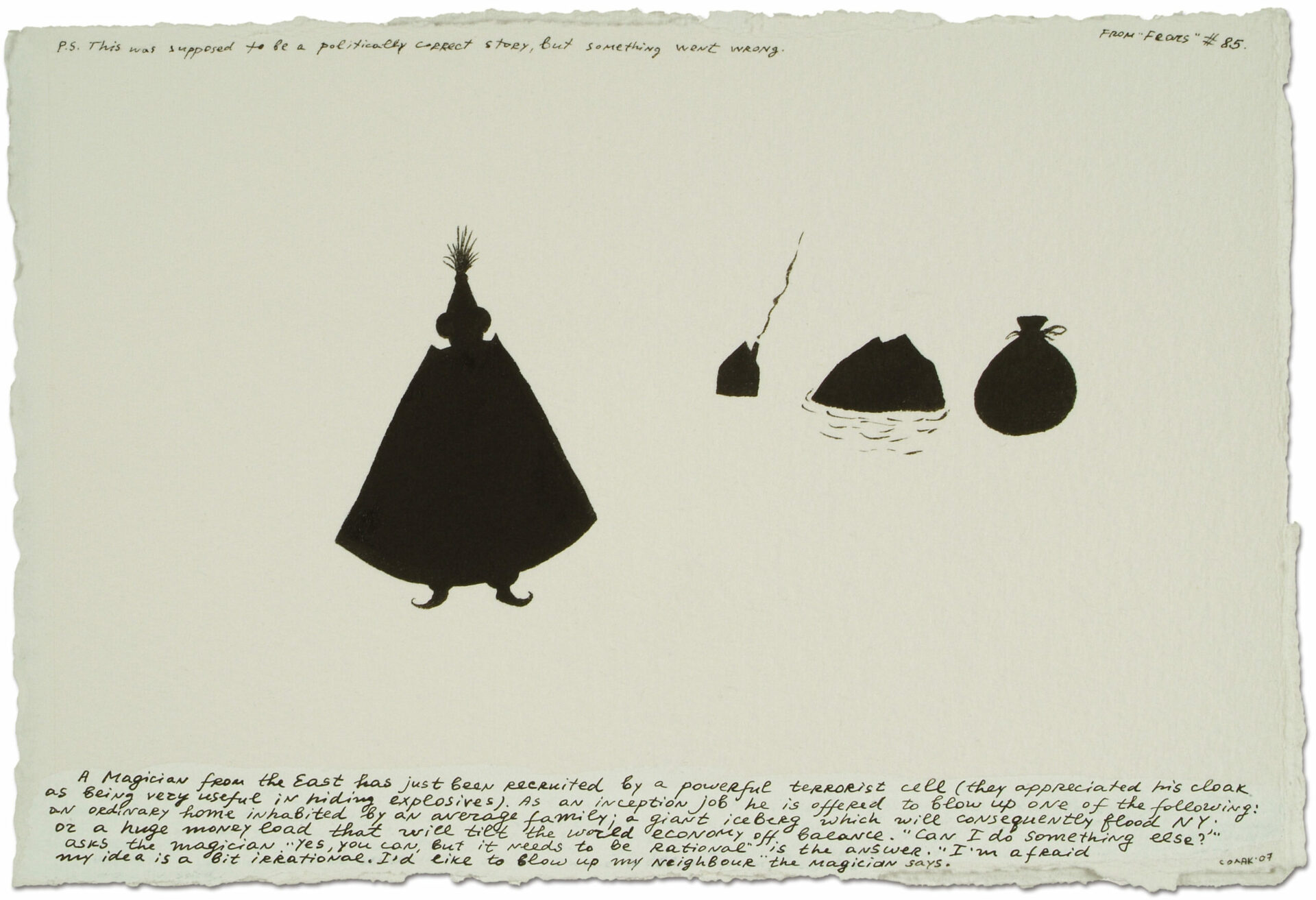

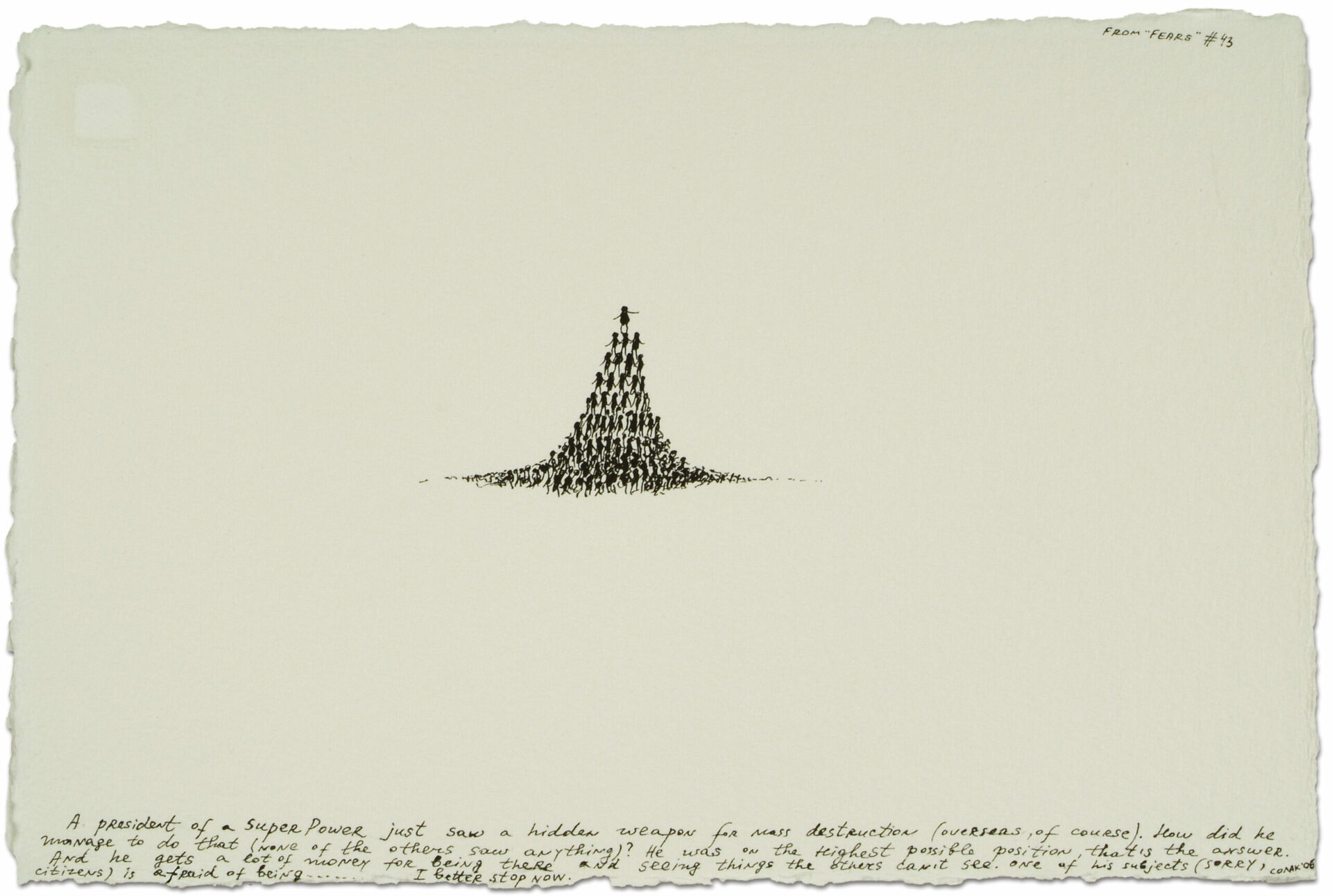

Fears #85 & Fears #43, 2006-2007.

Photos: Angel Tzvetanov, courtesy of

Arndt & Partner, Berlin & Zurich

While anthropologists in the United States are quite happy to study forms of paranoia in the general population, they rarely analyse the conception of power underlying such paranoia and even more rarely the performance of the elites who invoke more and more each day “transparency” in the exercise of democratic power. George Marcus believes that it would be more productive to examine the connection between transparency and conspiracy in the new world order.13 13 - George E. Marcus and Michael G. Powell, op. cit., 233.

The political use of the fear of terrorism recalls the Mafia’s logic of terror when it seeks to maintain order and omertà. Some of those who study the Mafia say that it is a true totalitarian system.14 14 - Leonardo Sciascia, La Sicile comme métaphore (Paris: Stock, 1979), 50. The art of confusion is not only carried out, it is also staged. Can we ignore this dimension of power? False conspiracies de-legitimize the true ones. From this point of view, we have to think of the conspiracy theory as a political weapon: it makes it possible to recreate cohesiveness out of fear of being either suspected of enemy sympathies or accused of indulging in conspiracy theories. The resulting self-censorship rectifies any deviation which would threaten the system’s fragile equilibrium.

We must, in fact, come to see terrorism and its repression as a two-faced Janus: each feeds the other and the terror under which we suffer in our day-to-day lives grows accordingly. In Michael Moore’s film Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), there is suggestion of links, whose exact nature is not revealed, between the Bush and bin Laden families. In a moment of parody in the Wachowski brothers’ film V for Vendetta (2006), the terrorist and the media dictator have one and the same face. This strange amalgam bears a truth: in the case of terrorism, the important thing is not the terrorist act itself but its media exposure. In this case, we no longer know who is serving whom. Media frenzies create confusion. The lucubration which results from these staggering acts is a part of this: the conspiracy theories surrounding acts of terrorism are a part of the business of terror. They serve the political interests which confront each other around the event. It is quite significant that no attempt is made to dissipate the conspiratorial mindset. In conditions such as these, how can we be surprised to see the reappearance of the “despotic machines” of paranoia?

[Translated from the French by Timothy Barnard]