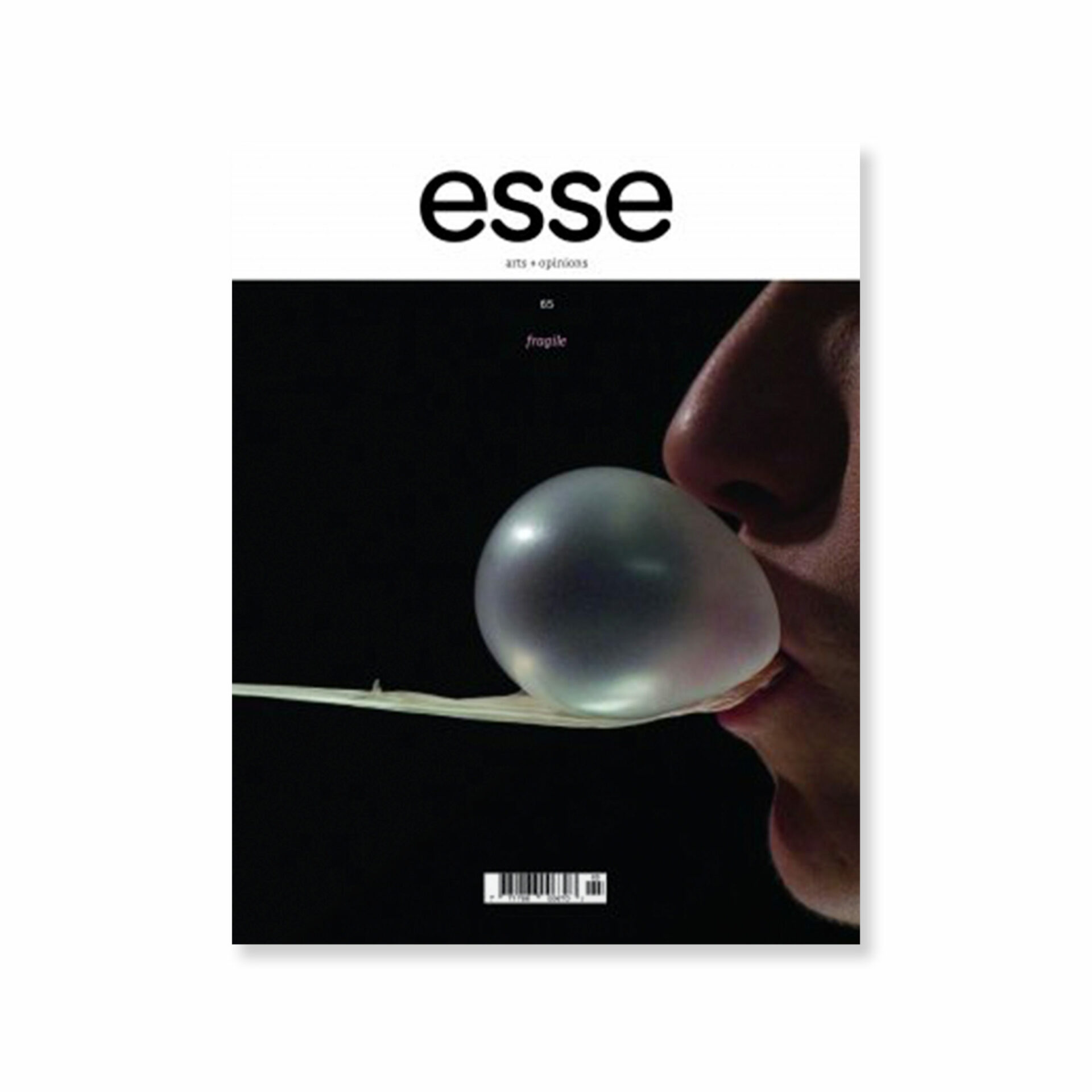

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Nervous Culture

The disposition of Canada’s “nervous culture” resides in its political mandates towards terror, distinguishing it from the “paranoid culture” manifest most pertinently in the U.S.A./U.K. The Canadian military operates primarily as a peacekeeping force, as opposed to the interventionist policies of the American and British armed forces, which are used primarily to forge borders between nations.

Paranoid culture can be understood as a set of post 9/11 sensibilities resulting from the seismic shift and subsequent reshaping of global communication, economic, surveillance, security, and transport networks. These transformations are not brought to bear by the U.S.A./ U.K.’s decision to invade Iraq alone, but reside in a more encompassing logic of economic and social control of which the invasion of Iraq is the most visible component. Paranoid culture is constructed from an integrated fear of an unknown and unidentifiable enemy, a psychological economy manifesting itself in the collective anxiety over the “sleeper cell.” This new formation of terrorism is defined by its aim to go beyond merely integrating itself into the fabric of everyday life. The sleeper cell resituates the terrorist paradigm by becoming a valued member of a community. Camouflaging his/her operations in earned responsibilities causes society at large to question its most basic systems of relationship building and social hierarchies when the cell activates.

9/11 is unique in that it marks a global paranoid culture where fear of the unidentifiable travels from the United States to several points globally. Because Canadian foreign policy does not employ its military industrial complex to inscribe external boundaries by force, Canadian socio-political culture remains nervous rather than paranoid. By way of example, the government’s attitudes towards mediatization of its training camps expose a more laissez-faire attitude than could ever be expected in the U.K./U.S.A.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The “training camp” holds connotations of a covert site of terrorist education. Occidental versions of training soldiers in anti-terror techniques are equally as annexed from media focus or speculation when located in the U.S.A./U.K. The openness of Canada’s camps is representative of its nervousness, demonstrating concern but not concealing its tactics for engaging with it.

While participating within the economic and military nexus of a post-9/11 order, Canada nevertheless remains peripheral on the radar of immediate threat due to foreign policy strategies such as its promotion of diplomacy over military action in Iraq. Canada’s international relations do not channel anxiety into paranoia, rather, they tacitly observe as a nervous witness of struggle.

Nervous Architecture

Pretendahar by Never Lopez is a series of photographs documenting the Canadian Indoor Urban Operations Training Centre near Toronto that “prepares” Canadian troops for effective combat in Afghani urban environments. The training facility, located in an airplane hangar, features a refugee camp, community centre and shantytown, organized in a gridded cellular manner resembling the cubicles of an office.

The photographs reveal a series of “nervous” spaces—the ventilation and structural systems of the hangar comprise the majority of the installation’s images. These shots of Pretendahar reveal a visceral space possessing a nervous structure that supports a cellular system within it.

Such spatial organization recalls Foucault’s analysis of Bentham’s 1785 panopticon, where he argues that the prison’s cellular space allowed for effective rehabilitation through surveillance and repetition. This notion of cellular surveillance is preserved in Pretendahar, broken up into a gridlike city; it structures the concomitant disciplinary techniques of the Canadian Army.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Commenting on Pretendahar’s training tactics in Toronto’s National Post, one officer remarks that it produces “muscle memory.” This tactic, achieved through repetition, is borne out through the spatial paradigm of the martial body. However, Pretendahar’s spatiality short-circuits between the nervous grid and the muscle. The information transmitted appears to fail to result in a coherent replica of middle-eastern spatiality. Rather than replicating the other, it is a structural projection of the occidental self, the antithesis of Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde arabe in Paris, with its skin of 240 motor-controlled apertures that react to sunlight.

Pretendahar simply presumes that the other extends the self’s spatial constructs. Its architecture is capable of handling occidental guerrilla warfare, but does not appear suited to the spatially responsive, mutating and nomadic structure of warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Never Lopez highlights the cellular spatiality of the training camp, the simulated chaos in its cubicle-like architecture suggesting the aftermath of a western office party gone awry whilst attempting to mimic the look of Kandahar. Structured by Cartesian logic, overhead grids of electrical, air conditioning, surveillance and fire systems sustain the hangar. This unreal life-support system, absent in Kandahar, manifests itself on a micro-level, as the office furniture and anti-Canadian propaganda painted upon the walls mocks space instead of defining Afghani social experience. Training on the cellular model with logistic structuring procured from the realm of a reality TV show, Pretendahar rehearses for an unrealizable experience.

Nervous Body

As the cellular space dictates movement, the soldiers exist as simulated antibodies, navigating the arterial passageways of Pretendahar, attempting to locate the debilitating elements within the body whilst being the foreign elements within the system. Akin to the passengers in the 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, about a group of scientists journeying inside a wounded diplomat’s body to repair it, soldiers journey into the fictionalised body of Pretendahar attempting to locate simulated potential threats to its structure. Fantastic Voyage is dominated by Cold War logic where an enemy can be identified; within Pretendahar this concept is not so simple. Here, the logic posits a fictional nexus of locating a disembodied enemy within the social corpus through the friction of disinformation.

At the climax of Fantastic Voyage, post-op, the miniaturized scientists exit the body, and through scientific endeavour, grow back to their normal size. The goal of Pretendahar is to grow out of the hangar’s body, the soldiers growing in confidence, experience and knowledge that will enable them to endure without the support system of surveillance and the safety of the simulated environment. Once blooded in Pretendahar, the soldier is presumed to shed the nervous skin developed in the expectation of traversing future hostile urban environments.

The scientific and distilled nature of Never Lopez’s clinical photographs exposes the environment at rest, absent of a resolution of bodies and thus deprived of its dynamism. This system without a body implicates the art-making process within Never Lopez’s photographs. Pretendahar supplies us with documents that look strikingly like contemporary installation art, representing a chilling vision of military culture imitating art. Given that Israeli Defence Forces “think tanks” currently utilize the same theorists (Debord, Virilio, and Deleuze and Guattari) as do many contemporary artists, an anxiety surrounding socio-political location has developed.

As cultural producers and commentators, we should feel anxious as Never Lopez draws the larger picture of military training into his lens and onto his iris, and then enlarges and re-exposes it for the viewer to witness. These photographs document the ushering in of a new era of uncertainty. As strategies of cultural production become employed as martial tactics, they force us to contemplate our own personal rules of engagement within the everyday of a nervous culture—a social network whose traditionally cultured defence systems of philosophy are in the process of being co-opted and re-territorialized by the military-industrial-culture complex.