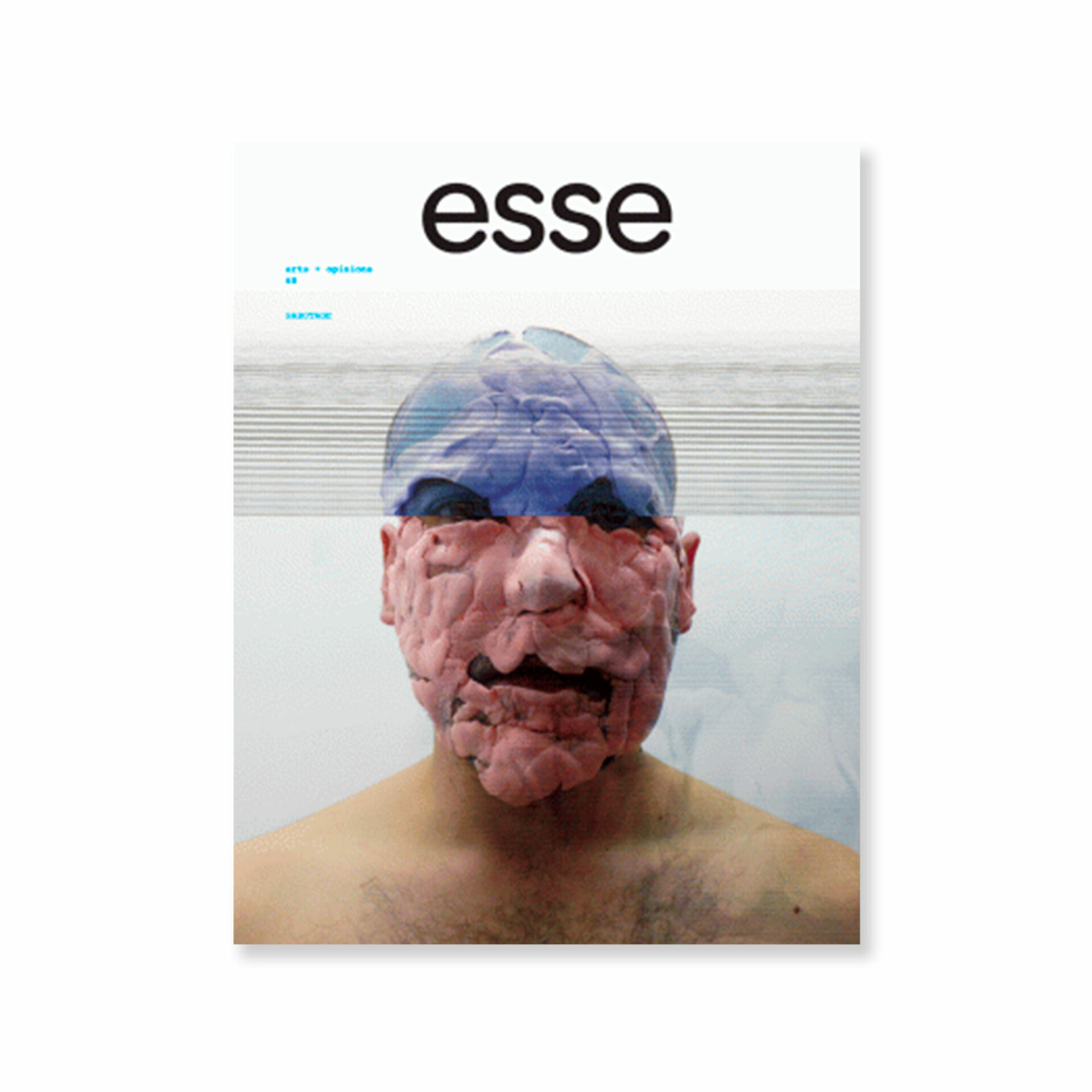

photo : permission de l'artiste | courtesy of the artist

“One of the most unaccountable and disgusting customs that I have ever met in the Indian country... I should wish that it might be extinguished before it be more fully recorded.”

– George Catlin

The custom that George Catlin, a white America painter and “specialist” of the representation of Native American ways, is referring to is that of the Berdashe. “Used indiscriminately refers to homosexuals, bisexuals, androgynes, transvestites, hermaphrodites and eunuchs,”1 1 - Pierrette Déesy, “The Berdaches: ‘Man-Woman’ in North America”, English translation by S. M. Van Wyck, 1993, never published in its entirety of “L’homme-femme. (Les Berdashes en Amérique du Nord),” Libre – politique, anthropologie, philosophie (Paris, Payot: 1978): 57-102. The article is available on line in the collection “Les classiques des sciences sociales,” Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, at: http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/desy_pierrette/homme_femme_Berdashe /homme_femme.html the term Berdashe is more specifically associated with men or women who, in some Native American tribes, freely choose to take on the social role of the opposite sex by cross-dressing and carrying out the daily tasks of their adopted gender. Catlin’s highly ethnocentric and profoundly puritan quote,2 2 - The George Catlin quotation displayed in the MMFA is taken from From Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, published in London in 1844. which was placed as a preamble on the wall adjacent to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ exhibition room where Kent Monkman’s work Dance to the Berdashe was on display from May 6 to October 4, 2009, abruptly grabs the viewer’s attention and accurately reflects a sombre image of ethnological excesses. Though, as we know the colonial undertaking succeeded in making the Berdashe disappear, Kent Monkman proudly spells his/her return.

A multidisciplinary artist of Anglo-Irish and Cree ancestry, Monkman casts a critical look at North American artistic canons throughout his work. By way of quotations and visual references he uses different mediums to revisit the visual repertory from which the imagery of the “New World” was built up, and this by paying particular attention to portraits taken of First Nations. The artist’s works, which are like genealogical allegories of representation on North American territory, aim nothing less than to deconstruct colonial mythologies in order to re-establish somewhat of a (multi)cultural equilibrium.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In the style and with the mastery of thenineteenth-century romantic landscape artists, Monkman reworks certain well-known paintings in order to breathe new life into them and to provide another point of view — one that is more contemporary and critical. The imposing painting, Trappers of Men (2006), recently acquired by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, for example, displays a group of men who are curiously staged in a sublime landscape by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) originally titled Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868). In Monkman’s depiction the Sierra Nevada becomes a partially anachronistictableau vivant in which the power relations between the various characters are played out. Notably, one encounters Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) a white American photographer who — even though he’s distracted due to the appearance of a masculine Venus in drag — is getting ready to take a “traditional” photograph of two Amerindians (it’s worth pointing out that one of the two models is just about to don a long black wig equipped with a feather). In the centre one sees Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) taking on Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) who’s in the process of painting one of his primary colour “checkerboards.” The altercation between the two men leads to a flow of “drippings”on an animal skin that an Amerindian artist uses as a canvas. Standing next to this Indian man is anineteenth-century artist — most probably George Catlin (1796-1872) — who gathers doodles and notes about the Aboriginal world.

Besides its many historical, visual and iconographic references to important art world figures and old artworks, Monkman’s pictorial work, which is both kitsch and caustic, is evidently charged with a strong homoerotic tension that notably echoes a desire — often troubled and malevolent — for the Other. All the while insinuating that a certain number of exchanges (other than material) occurred between Amerindians and Europeans, the artist’s work upholds that the sexual oppression of the First Nations people went hand in hand with racial oppression. Guided by Judeo-Christian values, the European ethnographic gaze — male, white, heterosexual — condemned (and at times even occulted) some sexual practices, such as the Berdashe, which did not correspond to the moral principles imported from the “old continent.”

Monkman’s latest video installation is a response to thefifty-sixth letter of Catlin’s memoir in which he condemns the existence of the Berdashe, but also to one of his paintings called Dance to the Berdashe depicting a ceremony in honour of this singular character. As one would expect, far from disapproving of the Berdashe’s hybridity, Monkman’s work glorifies it. At the outset, a hand wearing a red glove draws “primitive” silhouettes on four bison-skin shaped projection screens, the flat drawings then becoming suddenly animated and brought back to life in the guise of Native warriors wearing red, white and black costumes that echo traditional Amerindian outfits updated for today’s tastes. These dancer-warriors proceed to athletically shake and move to musical rhythms occasionally interwoven with a cappella singing, flutes, breathing and screaming.3 3 - Inspired by traditional pow-wows and contemporary dance, the choreography of the dancers was developed by Michael Greyeyes and the music by Phil Strong. Various musical movements, each one punctuated by a crescendo, maintain a certain dramatic tension that is entirely sustained by the dancers’ expression. The group forms a circle around a fifth “bison skin” suspended in the space, as they impatiently await the arrival of the celebrated one.

At first crouching, the Berdashe appears like a mirage, somewhat out of focus. He then rises on platform shoes in the middle of the room which suddenly lights up under his aura. His long black hair, long fringedress and red scarf wave in the wind. And to a rousing techno beat he begins turning about himself as he languishingly sways his hips. Just as in Catlin’s work the Berdashe presented here is a man dressed as a woman. To be more precise it’s the dancer Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman’s fictional alter ego. A flamboyant character, proud and glamorous and, if one wants, a brave and audacious drag queen — present in most of the artist’s works4 4 - The Venus in the painting Trappers of Men (2006) is Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. — who has come to metaphorically reclaim territories that are his/her due.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

While there is much mobilization nowadays to counter homophobia, Monkman rightly sets the record straight in recalling that it’s the English and French colonizers who imposed repressive sexual norms on our society through their conservative values. Though certainly singular, the Berdashe was nevertheless accepted in many Aboriginal communities who were more libertarian in sexual matters and gave free rein to this third sex. According to Monkman, Christianization unfortunately had negative impacts on Aboriginal sexuality.5 5 - Kent Monkman, The Impact of Christianity on Aboriginal Sexuality, Cybermuse, accessed at: http://cybermuse.beaux-arts.ca/cybermuse/docs/MonkmanClip6_e.pdf Due to the inculcation of homophobia the hybrid male-female figures disappeared from Native communities.

“Do Europeans have Berdashes in their cultures?” the curator Cathy Mattes asks Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. “No, and their world was lacking the Berdashe to provide a healing mediation of the genders,”6 6 - Cathy Mattes, “An Interview with Miss Chief Eagle Testickle,” Kent Monkman:The Triumph of the Mischief (Hamilton: Art Gallery of Hamilton, 2007), 110. Miss Chief responds. Miss Chief Testickle applies a transcultural electroshock to counter homophobia and racial discrimination. It’s up to us now to join in the dance and free our minds.

[Translated from the French by Bernard Schütze]