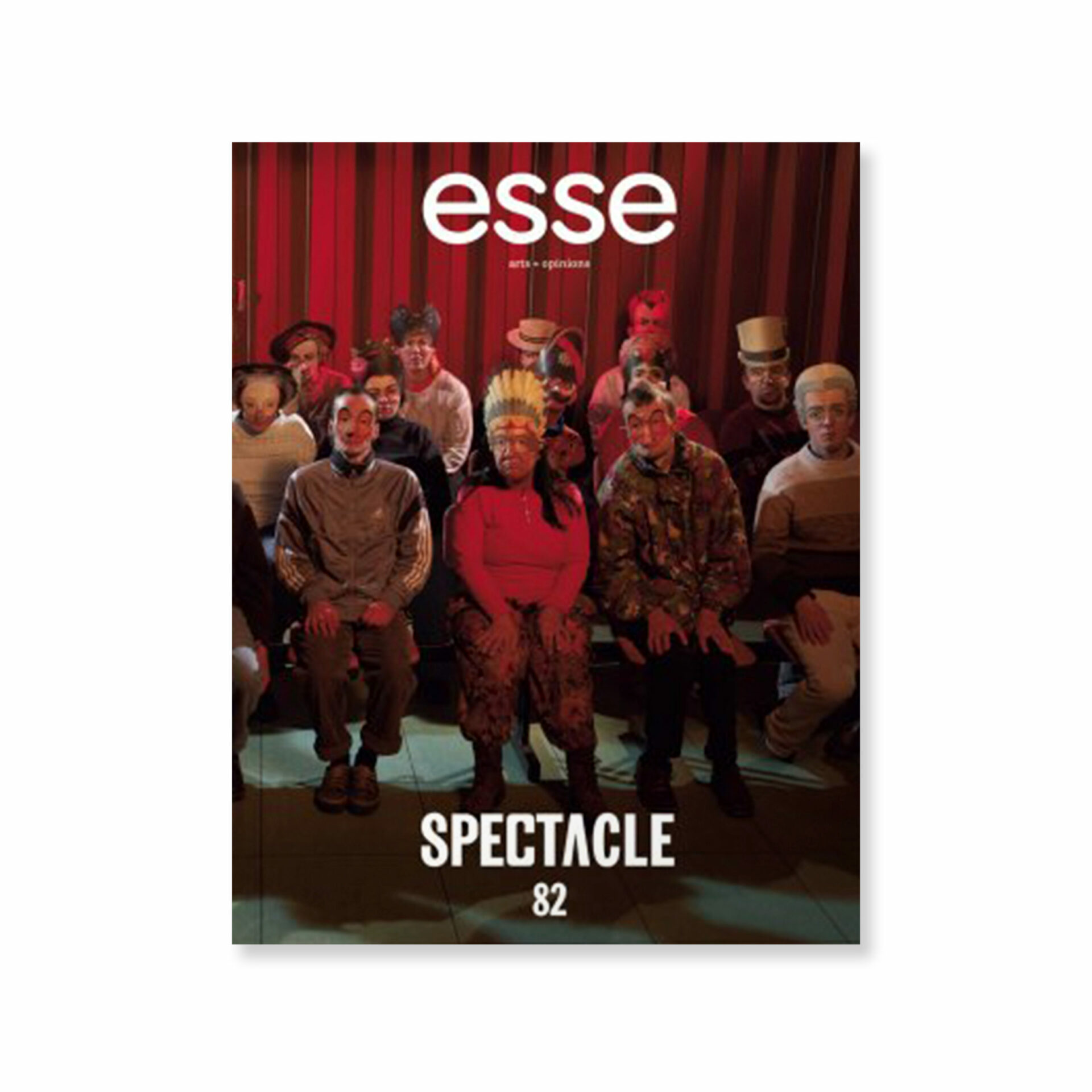

How can one make art after reading Guy Debord? Indeed, his diagnosis of a culture drowned in “spectacular contemplation”1 1 - Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, translated by Black & Red Books (Detroit: Black & Red Books, 1977), 184 (consulted online at http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/debord/society.htm). and of an art that must, if it is not to lose its soul, set up its own “dissolution” and “supersession” in the political sphere2 2 - Ibid., 190. appears to be an impasse. In 2000, the curators of Au-delà du spectacle3 3 - Presented at several venues, including the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, and Centre Pompidou, in Paris. proposed to get around the problem by summoning the more hedonistic concept, entertained by generations of thinkers, of the world as theatre.4 4 - One thinks of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Act II, Scene VII: “All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players.” They underscored the moralism associated with the sense of guilt regarding the enjoyment of entertainment that Debord’s idea conveyed, thus diminishing its import.5 5 - Au-delà du spectacle, exhibition journal (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2000), 3. But their argument begs the question of the recuperation of art through the spectacle. More recently, Hou Hanru, curator of the 2009 Biennale de Lyon, titled The Spectacle of the Everyday, broached the question more directly by first positing “that there is no longer any ‘outside’ for the society of the spectacle in the age of globalisation,” although he added that this does not exclude the possibility of taking a critical artistic stance by “negotiating subversively with such a condition of ‘no-outside.’”6 6 - Hou Hanru, “The Spectacle of the Everyday,” introduction, in Xe Biennale de Lyon: The Spectacle of the Everyday, exhibition catalogue(accessed at http://www.mac-lyon.com/static/mac/contenu/fichiers/dossiers_presse/2009/bac2009_en.pdf), 2009, 12. But does not the neat oxymoron in this formulation — can we imagine a subversive person negotiating, or a negotiator being subversive? — suggest the figure of the serpent biting its tail? We are thus back at the heart of the issue: can art escape the society of the spectacle?

photo : © Nicolas Boone

In his film Transbup (2010), Nicolas Boone7 7 - Having obtained a degree from the Paris ENSBA and pursued further studies in Lyon, Nicolas Boone has exhibited at Point Ephémère and the Maison Rouge and often presents films at the FID in Marseille. See nicolasboone.net/. also engages with Debord’s theory, though he adopts a less optimistic perspective. One of his characters — or, more precisely, an avatar of one of his characters, a computer technician and family man who, in a virtual world, is a punk activist fighting a totalitarian system called B8 8 - “B” for “BUP,” an anagram for “PUB,” the subject of a series of films (see below). (The following quotation is our translation.) — says, “We are in a modern dictatorship. There is no separation. Even the protest against B is within B. Both capitalism and presumed anti-capitalism organize life according to the world of spectacle. It is not a matter of developing a show of refusal but of refusing the show . . . . But B always coopts us.” Greatly inspired by Debord and the Situationists,9 9 - See “La Cinquième conférence de l’IS à Göteborg,” IS, No. 7 (April 1962), 27 – 28. and spoken in this context, these words recall the “no-outside” condition of the society of the spectacle: with the film-within-the-film device, the animation multiplying the cinematic fiction, the Debordian problem seems to be posed from the bottom of an abyss. In other of Boone’s productions, the proliferation of actors, episodes, or references creates bewildering mazes in which one is submerged and lost, until that recurring moment when a slippage occurs and everything goes awry. Can one escape it?

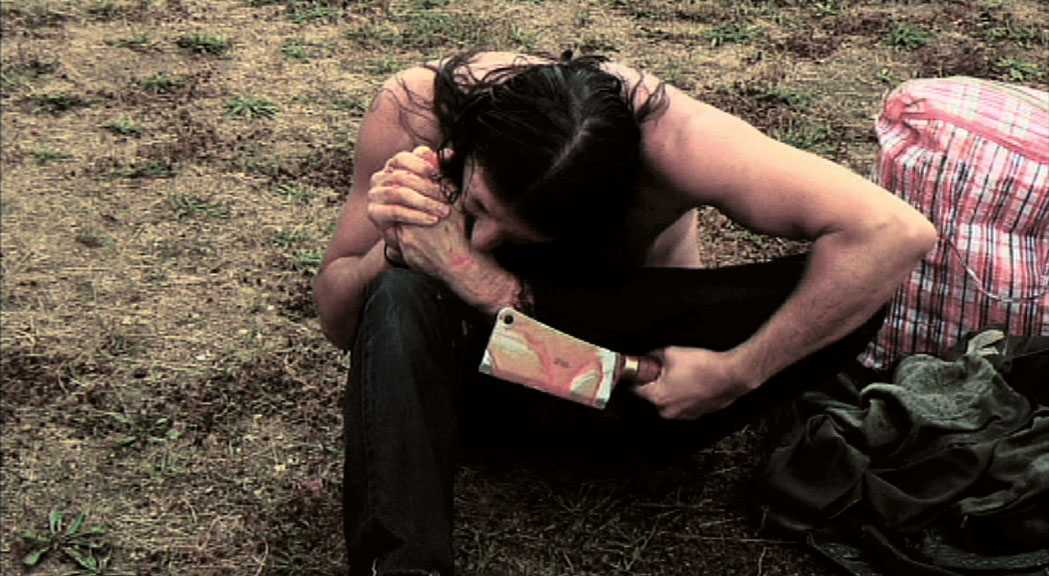

Boone’s early productions are marked by excess and overabundance. Many spectacular elements borrowed from the world of cinema are called forth, as if artists born after the advent of mass culture had to begin by itemizing the elements of that world. From his very first performances, Les films pour une fois (2002) — mock shootings of Hollywood mega-productions — he takes up the cinematic clichés: megaphone in hand, the director’s authoritarian posture, and a crowd of extras, all characteristic of major productions since the Hollywood industry’s early days, with Griffith’s Intolerance. In his earliest works, then, spectators are immersed in the society of spectacle, besieged by the action that they are witnessing. In La transhumance fantastique (2006), for instance, Boone brought together a great number of extras in a mock conquest of the West to recount the migration of urban populations to the countryside. As their resettlement involves building housing and infrastructure, the film playfully shows us major construction sites and lots strewn with backhoes. Another recurrent motif punctuating the sequences in Boone’s films are speeches, uttered in equally spectacular fashion: a mayor perched on a phone booth berating a crowd, real estate promoters promising happiness to residents, and so on. Yet, in contrast to these moments of public jubilation, La transhumance fantastique includes more ambiguous scenes, inspired by such gore fests as Peter Jackson’s Bad Taste — scenes in which festive gatherings become general bloodbaths and everyone confusedly takes chainsaw and lawn mower to everyone else. The joyful spectacle turns against itself.

photos : © Nicolas Boone

photos : © Nicolas Boone

photos : © Nicolas Boone

photos : © Nicolas Boone

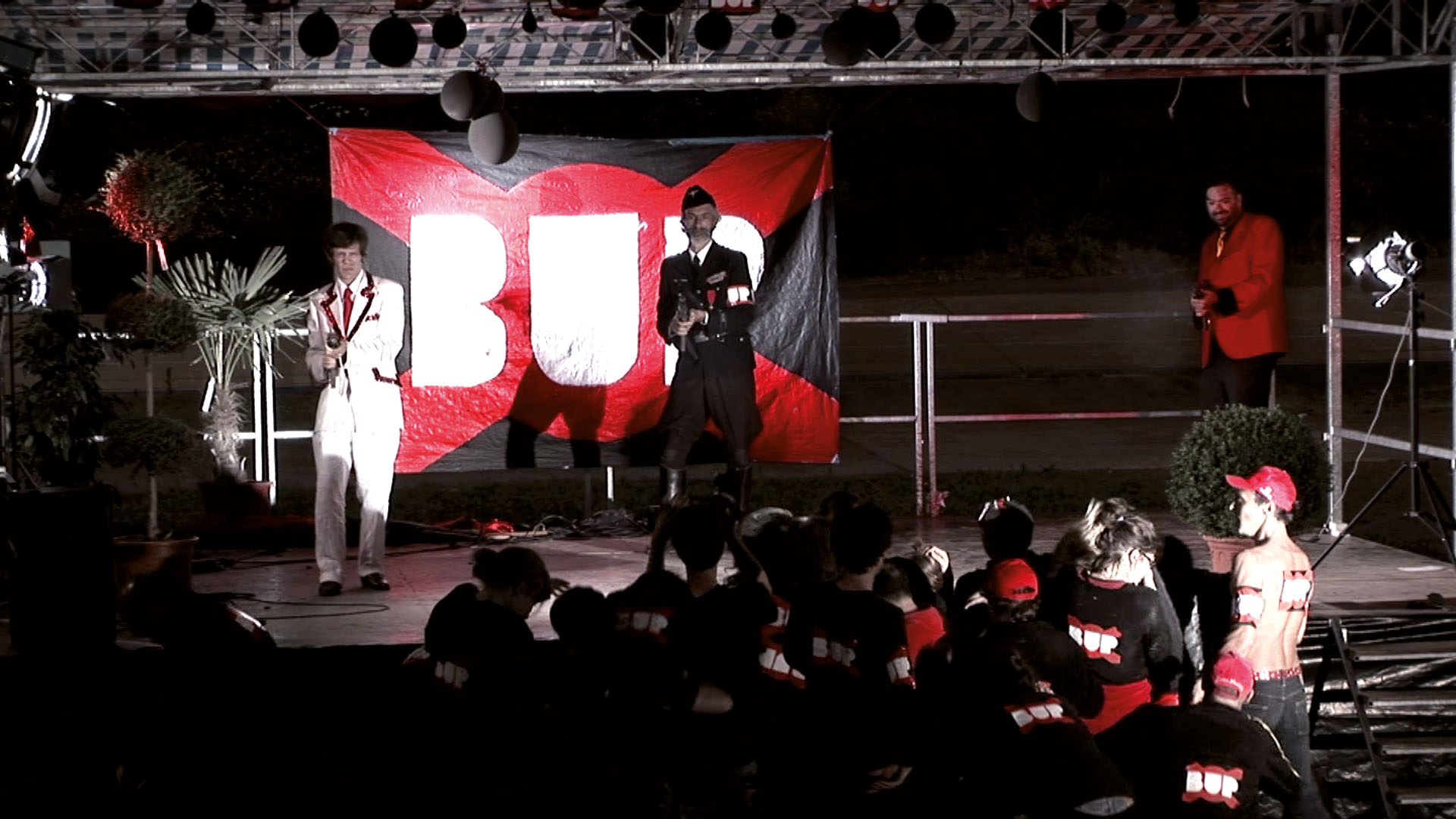

All of these elements are synthesized and brought to fever pitch in a more ambitious work, the BUP film and series (2010). In a Lynchian intensification (David Lynch’s Twin Peaks series, completed by the film Fire Walk with Me) that opens on the highly current issue of artists’ relationships with TV series,10 10 - See, for instance, “Séries télévisées — formes, fabriques, critiques,” Art Press 2, No. 32 (Winter 2014). they extol the virtues of a colourful, modernist — indeed, utopian — system that turns out totalitarian. In BUP Park, the second episode of the series, one character is trying to escape but is constantly stopped by crowds waving BUP placards, an obvious reference to the mock incarceration series The Prisoner. Some episodes put greater emphasis on BUP’s rapturous mood, especially Mega BUP, in which a supermarket scene becomes a highly ironic embodiment of ecstatic joy. But other episodes reveal the underpinnings of this artificial merriment through subtle and less-than-subtle shifts into horror. The mood is set, in fact, with the very first episode, BUP Ball. After grotesque fight scenes and a frenzied haka-like dance with a chainsaw, the episode ends with the image of a character eating his own foot. But the escalation reaches a peak in two episodes in which the grotesque veers into terror: BUP Show parodies a TV game show. Its colours — a Nazi aesthetic of red, black, and white — augur the worst, which transpires as game show participants are executed and the game organizers take orgiastic pleasure in the dead bodies. Worse still, Château BUP is a remake of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, in which, like the character eating his foot in the first episode, the series’ smooth, joyful world of appearance self-destructs in violent convulsions. The succession of BUP episodes organizes the overturning of the advertising world against itself, which can’t fail to recall an International Situationist maxim: “The fundamental characteristic of the modern spectacle is the staging of its own ruin.”11 11 - “Le Cinéma après Alain Renais,” IS, No. 3 (December 1959) (accessed at http://debordiana.chez.com/francais/is3.htm#cinema, (our translation). Although these early works rather point to excess, ruin may not be far away.

After the exuberance and saturation of the spectacular, Boone’s productions become more focused, with subtler references to the catalogue of images from cinematic history. The initial accumulations give way to long sequence shots, and the crowd scenes and promotion to more targeted and precise interrogations on the overlap of reality and fiction.

Made in four parts that inform each other, Les dépossédés (2013) fits within the tradition of works delving into conspiracy theories,12 12 - As in Laurent Grasso’s works, for instance. but it broaches the theme from one of its least-developed consequences: the alienation of the targeted population. The apocalyptic world evinced in some movie extravaganzas may not be far away (part 3, Expansion), nor may be such genres as paranormal and science fiction — through music in particular (part 1, L’ondulateur). But on the whole, Les dépossédés functions as a parable, part fable and part philosophy, as in the monologue that makes up part 2, La fin de la mort, which, in some respects, recalls the spectacular speeches in La transhumance fantastique and BUP. The discourse is emphatic and addressed directly to the audience. The actor who utters it, recruited after an extensive casting search, wears a blue satin jacket and a wide-collared white shirt that would make him right at home in a Quentin Tarantino film. But the content and the writing of the discourse steers the interpretation toward another universe. Written with great literary precision, the screenplay (co-authored by detective fiction writer Jean-Paul Jody), marshals sometimes fantastical conspiracy-theory arguments to suggest African-American history in a perspective that one might call Afro-futurism, articulated through colonial history and science fiction.13 13 - On history and the concept of Afro-futurism, see Cédric Vincent, “No (after)future,”

photo : © Nicolas Boone

A recent and more radical film, shot on a real set, picks up on the same themes, in particular that of a blissfully authoritarian village, while synthesizing them into a much stronger image than in previous productions. Le rêve de Bailu (2013) begins with the director’s cue — “Action!” — indicating that the characters are actors. One notices something odd about the style of the houses, for Bailu, with its restaurants and movie theatre, is a French tourist village in the middle of China. The karaoke sequence at the end of the film clues us in to an interpretation: in this village, everyone is playing a predetermined part. But who is the author? Who the director? We then remember a hint provided at the beginning: after an earthquake that had destroyed the region, the government had this artificial village built for the local population to live and work. Reality itself is a fiction.

In the same vein, Hillbrow (2014), filmed in the centre of Johannesburg, follows the itinerary of twenty characters played by local residents. They play at violence, against a backdrop composed of spectacular views of the now-abandoned modernist city, dominated by a 1970s tower and, crowning it, a huge Vodacom sign. Indeed, in some scenes, donning major international labels, the actors take an obvious delight in making a mockery of themselves. Then, revealing the heart of this infernal machinery, one character leads us into the great tower, Ponte City.14 14 - On the history of this tower, see Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse, Ponte City (Steidl Verlag, 2014). Built during the apartheid era to house wealthy families, it now lies empty, its central skylight more a yawning chasm than a ray of hope. The film is summed up metonymically with a holdup scene in a movie theatre: the aggressors rise up against the screen, the cries of their victims blending with the soundtrack, their faces leaping out of the shadows, lit up by rays of white light. The fiction is in the real. But this fiction will not end happily. The last scene is shot in the stadium built for the 2010 World Cup. It is already overgrown with vegetation. The camera follows a character who begins a long doleful ascent up the stairs beside the bleachers. Like him, all we can do is acknowledge that the festivities are over. The spectacle is in ruins.

photos : © Nicolas Boone

Between the orgies of gore and his tours of a derelict world, Boone’s work leaves little hope that the society of the spectacle will have a positive outcome.

An expression of Jean-François Lyotard’s may summarize the situation. In an essay on Jacques Monory’s Ciels, Lyotard concludes that the current world, in which technology allows for even the infinitude of interstellar space to become a reified spectacle, we can now only be “survivors or experimenters.”15 15 - Jean-François Lyotard, “Esthétique sublime du tueur à gages” (1984), in L’Assassinat de l’expérience par la peinture (Monory: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2013), 192 (our translation).

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]