photo : © Walid Raad, permission de la | courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut / Hamburg & Festival d’Automne, Paris

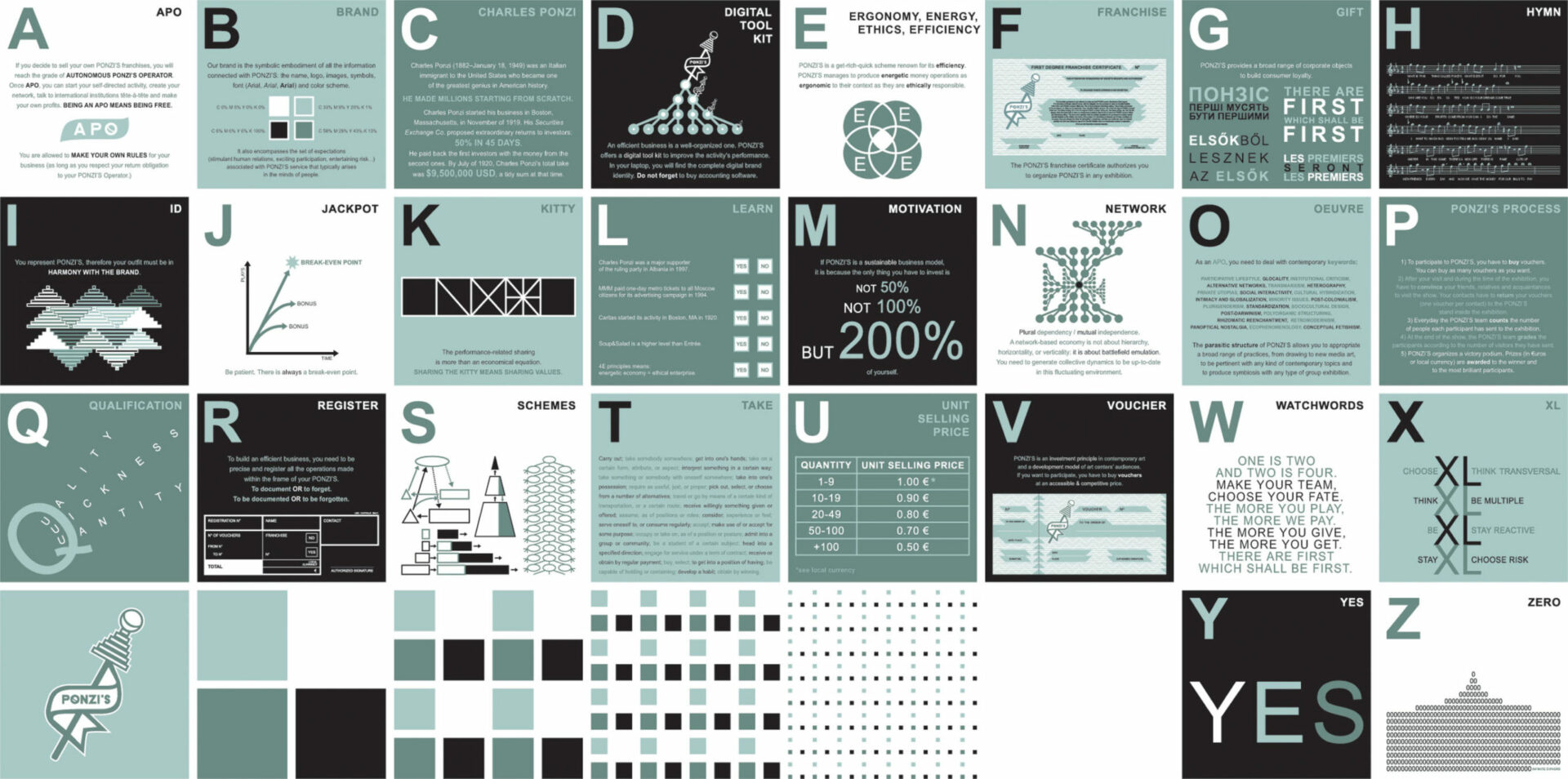

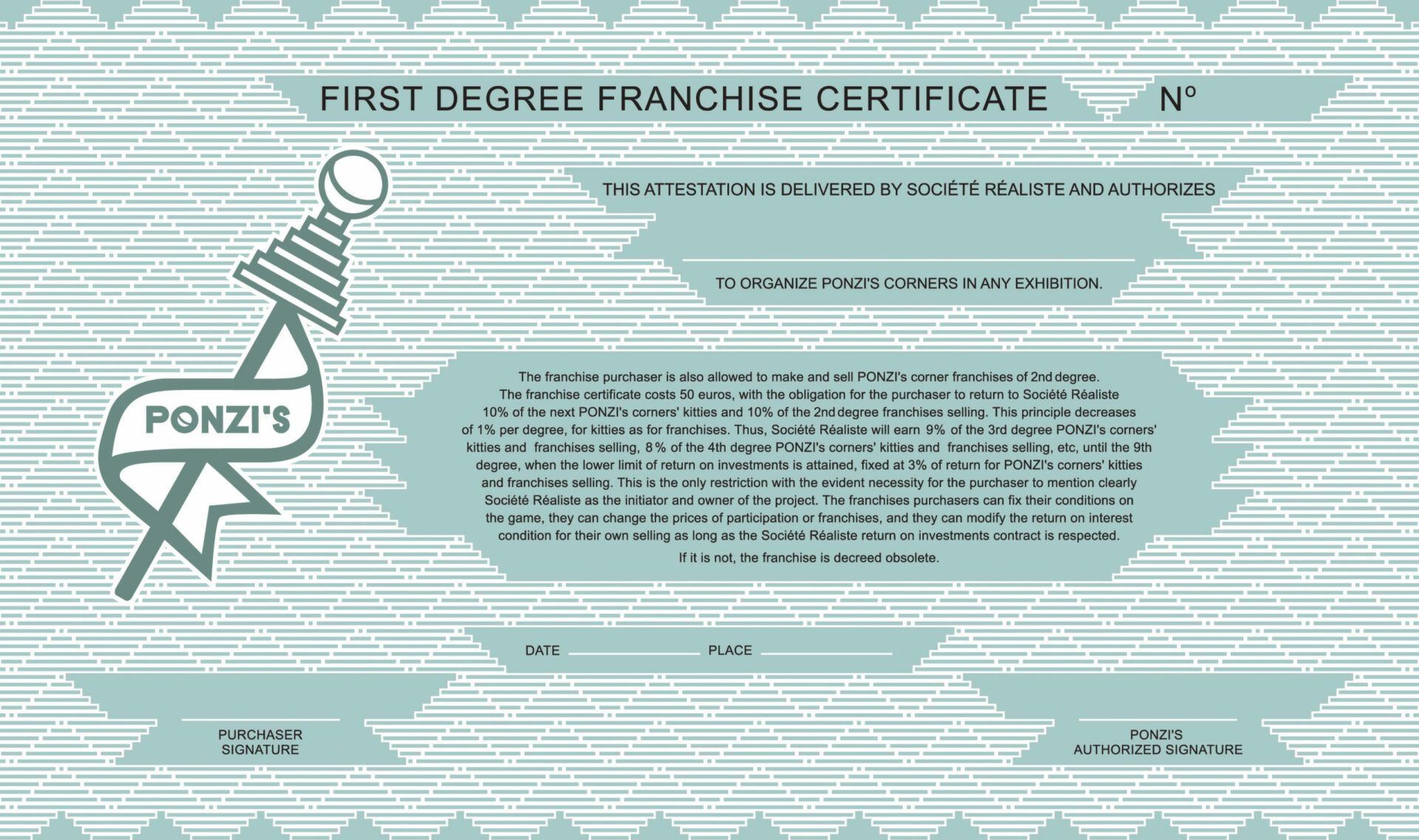

And if, above all else, relational aesthetics were an economy? Having tackled the aesthetic and ideological stakes of this 1990s1 1 - This article is a shortened version of a talk given on May 31, 2011 at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) in Paris, as part of the international colloquium Au nom de l’art. Enquête sur le statut ambigu des appellations artistiques de 1945 à nos jours, organized by Guitemie Maldonaldo, Katia Schneller, and Vanessa Théodoropoulou. revival of participatory practices in several articles,2 2 - The first was “L’artiste médiateur,” Artpress 22 (special edition on Écosystèmes du monde de l’art) (November 2001): 52-57. this question arose in light of PONZI’s (2006), a work by the artistic cooperative Société Réaliste. The piece was a critical satire of a relational economy based on the association of two models: the gift economy as it operates in contemporary economic and social networks and the pyramid scheme invented by Charles Ponzi.3 3 - For a description of the Ponzi’s scheme, see my article “In art we trust. Un art critique d’art” (2010), published on my blog at http://tristantremeau.blogspot.com. This article is the basis of my eponymous book to be published by éditions Al Dante, in Marseilles, in September of 2011. As I elaborate in a forthcoming book, these two models, among others, are the basis of a global financial apparatus now presenting itself as a retirement fund for artists, the Artist Pension Trust. To understand the connections between the relational aesthetic and the relational economy, one must go back to the end of the ‘90s, when an economic vocabulary took up considerable space in discourses on and about art, and more especially, in exhibitions — privileged moments of visibility and exchange. This was particularly striking in France where ideas growing out of commerce and TIC (theories of information and communication) — networks, connections, relationships, flux, transit, traffic, and information — were found in the titles of exhibitions and marked their theses: Traffic (organized by Nicolas Bourriaud at the the Capc de Bordeaux in 1996), Transit and Connexions implicites (by Christine Macel and Jean de Loisy respectively at the École des beaux-arts de Paris in 1997), Connivence (Biennale de Lyon, 2001), and Traversée (by Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Laurence Bossé at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris in 2001).

Connexion implicite was, in its thesis and method, no doubt the most eloquent manifestation of the substitution of the collective paradigm — favoured from the 1960s through the 1980s by artistic practices that positioned themselves as alternatives to the dominant liberal economic model4 4 - See Julie Ault, ed., Alternative Art New York 1965 – 1985 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002) and Blake Stimson & Gregory Sholette, eds., Collectivism after Modernism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). — by that of the network, which had become a flagship concept and implicitly included the others, in a context dominated by an apologetics for the new possibilities offered by the democratization of the Internet. “With whom am I connected?” today seems a more explicit statement of ties or identity than “to which national or religious group do I belong?” read the press release. “Thus, movements once founded on a shared political or aesthetic ideology are no longer current, while the networks traversing old categories give rise to a dynamic transnational or transcultural identity.”5 5 - From the press kit for the exhibition Connexions implicites, Paris, Énsb-a, from May13to July 13, 1997. To manifest the “temporary, rapid and effective organic associations” characterizing the new, networked art economy, the list of exhibiting artists was based on an initial list of artists with whom Fabrice Hybert had worked, at a time when he had positioned and distinguished himself as an artist-entrepreneur. These artists were invited, in turn, to name their associates, who, once named, were also questioned about their networks. In the end, the exhibition reconstructed an “international cartography of an implicit network,” in this case that of well-known emerging artists in the process of institutionalization (Douglas Gordon, Angela Bulloch, Maurizio Cattelan, Carsten Höller, Gabriel Orozco, Philippe Parreno, and Jason Rhoades, among others). Also included (through interviews published in the catalogue) were emerging curators, who were equally well-known and becoming institutionalized (Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Nicolas Bourriaud, Éric Troncy), and who shared a common portfolio of artists in their writing and curatorial activities.

Ponzi’s manager improvement classroom, vue d’installation | installation view, ICCA, Bucarest, 2006.

photos : permission de la | courtesy of Société Réaliste

We find almost all of these artists in the book Relational Aesthetics, published by Bourriaud in 1998. The book is a theoretical unification of diverse practices — with an ethical focus — as part of an aesthetic and ideological project of repairing social ties and the participative and democratic integration of the viewer in the name of the common good. Yet, for Troncy, what primarily unites the artists is their will to break down dominant models of group exhibitions.6 6 - See Eric Troncy, “Discours de la méthode” in Surface de Réparation (Bourgogne: Frac, 1994), reprinted in Le colonel Moutarde dans la bibliothéque avec le chandelier (texts 1988-1998) (Dijon: Les presses du réel), 81-97. Contrary to the logic of the traditional orchestration of works, or of isolated bodies of work, under the aegis of a curator, all the group shows organized by Troncy, Bourriaud, and Obrist convey this desire to entrust the production of the exhibitions to the artists, themselves moved by the desire to share and exchange territories, competencies, or even roles. And this, while conceiving of the aesthetic situations they create as “laboratory” spaces and as diversified moments of experimentation for the viewers. These notions of laboratory and experiment, also fashionable in the 1990s, were promoted in the writing of Obrist as vectors for a utopian new art economy, bringing together actors, artists, intermediaries, and assistants. In the catalogue for Utopia Station, which he co-organized with Molly Nesbit and Rirkrit Tiravanija for the 2003 Venice Biennial, he wrote that the exhibition integrated “the work of the artist, of intellectual and manual labourers,” in order for them to find themselves in “a larger kind of community, another kind of economy, a larger conversation, or another way of being.” And yet, as Boris Groÿs wrote, the so-called utopia of the new economy was already the daily reality of Obrist, and of most networked intellectual workers.7 7 - Boris Groÿs, cited by Lars Bang Larsen, “Do you feel it? Art, work, utopia and the real” in Art Lies 41: www.artlies.org/article.php?id=148&issue=41&s=0.

This situation is also characteristic of the integration of theories on the knowledge-based economy in post-industrial societies that have developed since Jean-François Lyotard critically defined their basis by explaining that, since 1979, knowledge risked being reduced to “informational merchandise,” to a pure process of reification.8 8 - Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984). Thus, in Obrist’s exhibitions, the networking of artists amongst themselves and the connections between the problematics of their work are frequently heightened in a mise-en-scène of the interdisciplinary connections between artists and researchers in the social and hard sciences. Furthermore, it is the simple fact of being connected and “living wired” — a kind of natural and enchanting cybernetic phenomenon — that is promoted as a value in itself. This is made evident in the recurrent representations of arborescent structures in the catalogues and on the websites accompanying the exhibitions, and as is stated in the first — unattributed — textual extract published on the back of the Traversée catalogue cover: “In our electrified world, the ‘web’ and ‘net’ world, electricity is in itself information. It’s a behaviour, a history. It’s the fluid shared by our old bodies of flesh and blood and all the new identities now being born. Human nerves and printed circuit maps carry the same current.” Connexions implicites already conveyed this ideology, inspired notably by Paul Virilio’s writing, which affirmed that actors in a network “before sharing a style… share a speed that accelerates the possibility of their acquiring knowledge, connections, imagination.” Beyond this, what the exhibitions conceived by Obrist, along with his obsessional practice of interviewing, and the hypertextuality of his catalogues testify to is a capturing of all kinds of things as information (artists’ names, exhibition venues, concepts, etc.), namely anything that might constitute capital — as it is conceived of in the theories of the knowledge-based economy — which he then monopolizes and associates with his name. He works like a trader, accumulating information in order to better situate his projects and reap the benefits of risk-free profit.

photo : permission de la | courtesy of Société Réaliste

photo : permission de la | courtesy of Société Réaliste

photo : permission de la | courtesy of Société Réaliste

Also striking in all of these exhibitions is the constant presence of the artists that led Bourriaud to develop his theory of relational aesthetics (Tiravanija, Parreno, Huyghe, Gonzalez-Foerster, Gillick, Gordon). Might these not be, fundamentally and above all else, an economy? What links these artists is less an aesthetic or ethical program — at its core, only Tiravanija’s process perfectly incarnates Bourriaud’s theory; the other artists adopt it only episodically — than an economic strategy for building an international network, one based on the exchange of gifts between artists, and between artists and curators. When a relational artist was invited to produce and show a work at a certain venue, he invited comrades to collaborate, who did the same for him on some other occasion, and so on. As the sociologist Jacques Godbout has shown, the three obligations of the gift, as defined by Marcel Mauss (giving, receiving, and reciprocating), characterize the ways of exchanging goods and services specific to contemporary social and economic networks, which function in favour of their members and not a public.9 9 - Jacques Godbout with Alain Caillé, The World of the Gift (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999). Thus, while Bourriaud’s discourse insists on the production of a sense of community among the viewers and through the kindly actions of relational artists, the reality of this art is above all a (re)production of a networked community-based economic model, in symbiosis with the existing liberal economy. And this model of relational economy has proven its effectiveness: the majority of the artists identified with relational aesthetics are present in key international markets of artistic visibility, and Obrist, as an exemplary relational curator, is recognized as one of the most influential players in the art world.

This being the case, it is not surprising that the model has been taken up and formalized by a finance firm: the Artist Pension Trust (APT).10 10 - www.aptglobal.org Created in 2004 by entrepreneur Moti Schniberg, advised by key players from the worlds of art (Hans Ulrich Obrist, Rirkit Tiravanija, Kiki Smith, David A. Ross, and John Baldessari are part of the consultative committee) and finance (bankers, insurers), the APT presents itself as a pension fund for emerging and mid-career artists (1,363 have already adhered to its financial program, divided up into eight regional APTs),11 11 - There are eight APTs in the world, each one occupying a geographical zone: New York, Los Angeles, Mexico, Berlin, London, Dubai, Mumbai, and Beijing. chosen by APT curator-consultants (independent and salaried curators). The artists who join the program must each invest twenty works over a twenty-year period. The APT claims to help the fund turn a profit (the total forecasted, at term, is 40,000 works by 2,000 artists) and to sell the work under the best possible terms, thanks to the firm’s multiple networks, generated by the paid participation of curator/consultants (who are on the committee of certain museums, write for particular magazines, advise specific collectors, or consult certain companies…). Thus, the APT aspires to act like an art market lobbyist to the advantage of its clients — the artists — and its investors — whose anonymity they maintain — by progressively building the largest art collection in the world: one able, through its importance and that of its networks, to influence the art market at a global level.

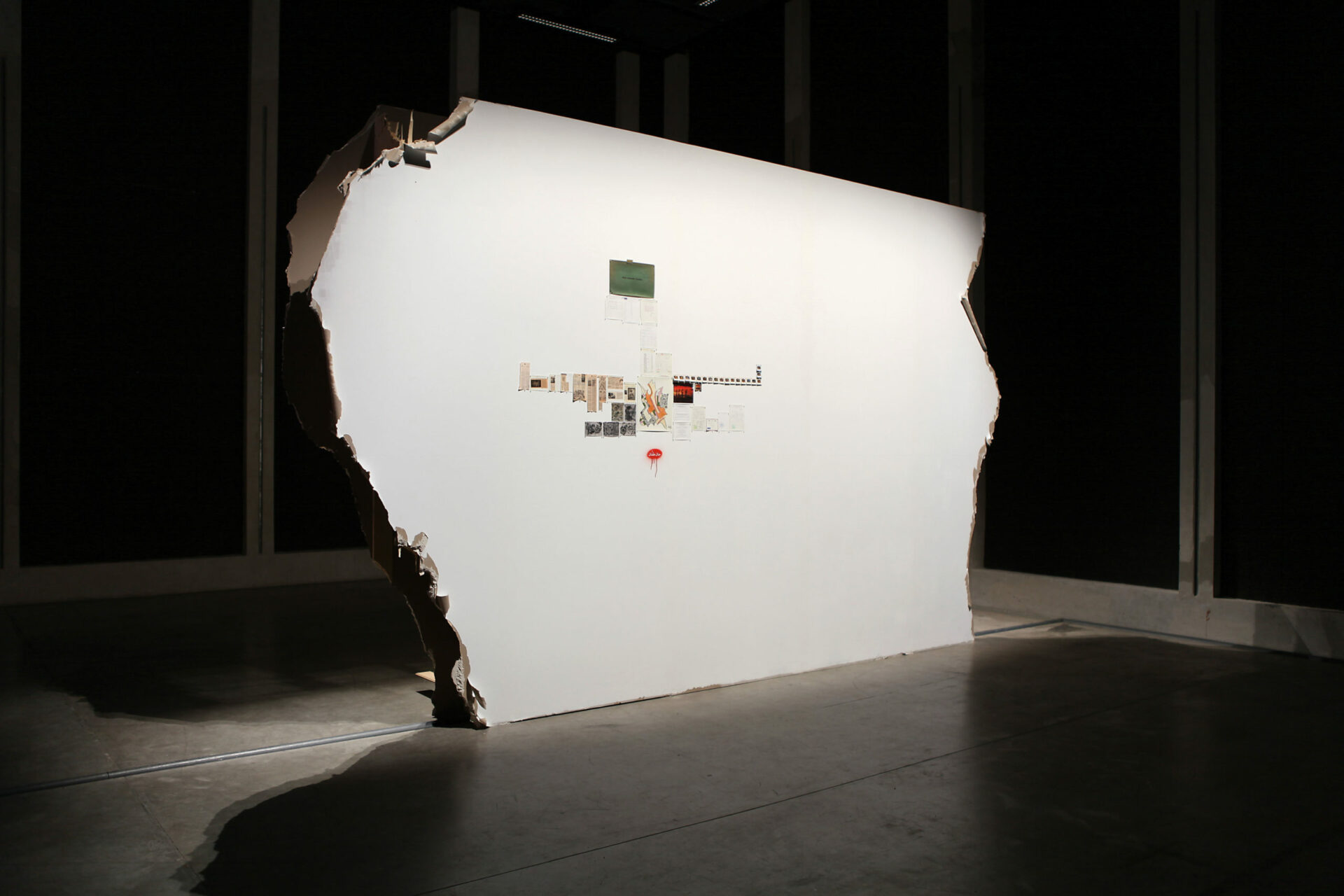

photo : © Walid Raad, permission de la | courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut / Hamburg & Festival d’Automne, Paris

photo : © Walid Raad, permission de la | courtesy

of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut / Hamburg & Festival d’Automne, Paris

In doing so, the APT also monopolizes information that is crucial for investors in determining the value of works. Where have they been exhibited? By whom? Who has written on a particular work? In what terms and in which magazine? Has an artist exhibited at a biennial, or is he or she going to? In which gallery? These questions are not unimportant, since the APT is a product of another firm, MutualArt.com, whose services include the sale, on an eponymous site, of precise information about the art market to investors.12 12 - www.mutualart.com As artist Walid Raad said in his performance/exhibition Scratching on Things I Could Disavow. A History of Art in the Arab World, presented at 104 in Paris during the autumn of 2010:13 13 - This project, since shown in Munich, Brussels, Berlin, and Vienna, was born of an invitation made to Walid Raad, in 2007, to join the APT in Dubai. Declining the invitation, he has since produced important research and interpretative work on the adherents and ends of this financial system. this information is gathered from the best sources, the APT’s network of curators, who, for once, are paid for the information they disseminate, in this case to investors in the retirement fund and those to whom MutualArt.com sell it. In fact, investors can directly contact the few hundred curator/consultants at APT over the phone through APT Intelligence, which bills for the advice and information provided ($350 per thirty minutes).14 14 - www.apt-intelligence.com It is in this way that the same methods are applied in the art world as those that prevail in the sector of communication networks, where the stakes are the monetization of relationships and transmitted information, both of which, henceforth, constitute a value: intrinsic capital that can be bought and sold.

One might doubt that the artists associated with relational aesthetics and Nicolas Bourriaud could have envisaged such a financial perspective, one signifying the radical reification of works of art — recognition reduced to the value of the tags assembled by the operators of APT and MutualArt.com. Nonetheless, the perfect ideological congruence of the relational economy and the development of knowledge-based and digital economies, proclaimed apologetically by exhibition curators associated with this aesthetic as of the latter half of the 1990s, make the existence of a financial apparatus like the APT less than surprising. And now, it could be considered as an exemplary case study for understanding and deciphering the working modes of the principle visible markets for contemporary art — ones that go beyond, well beyond, relational aesthetics.

[Translated from the French by Peter Dubé]