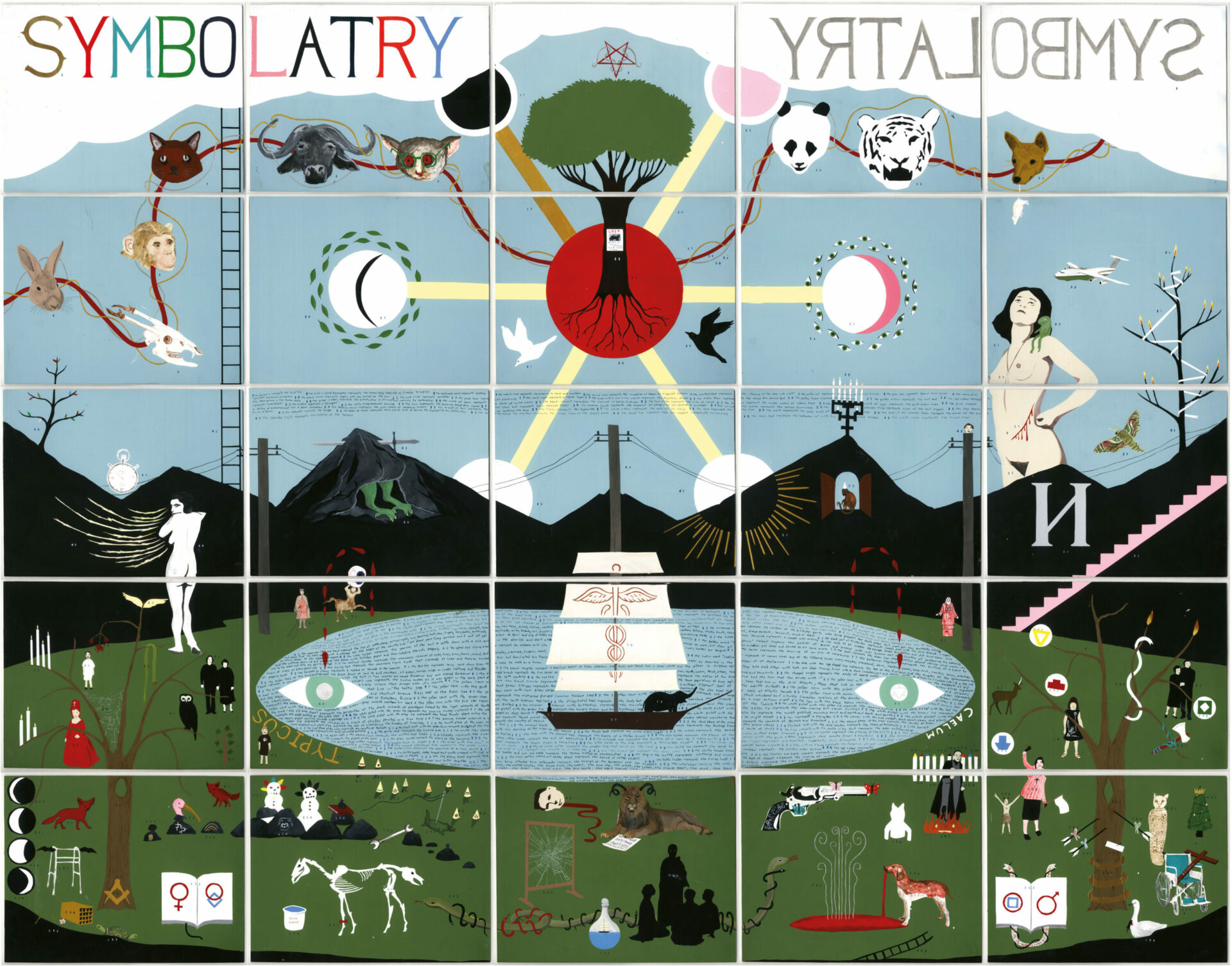

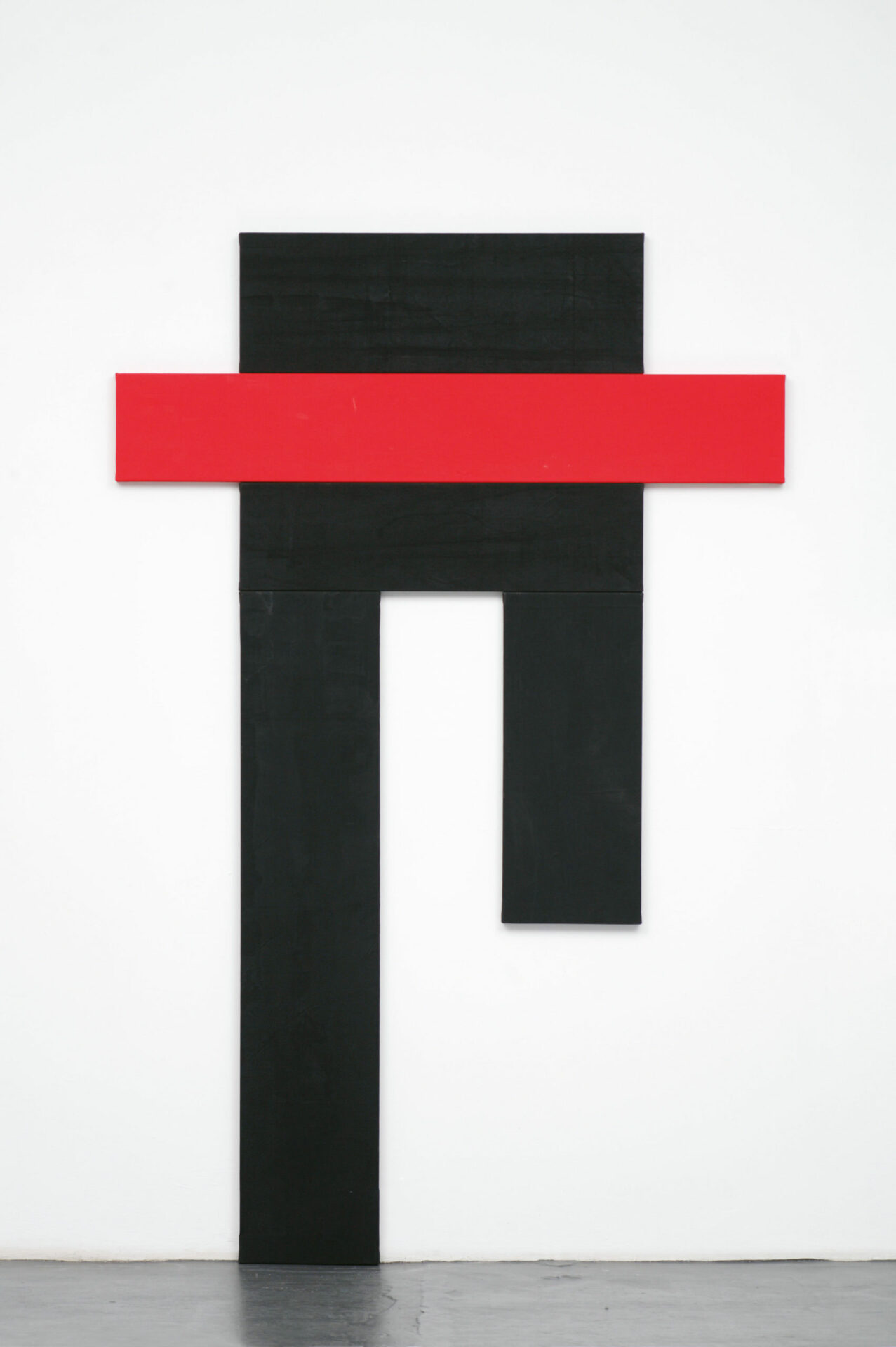

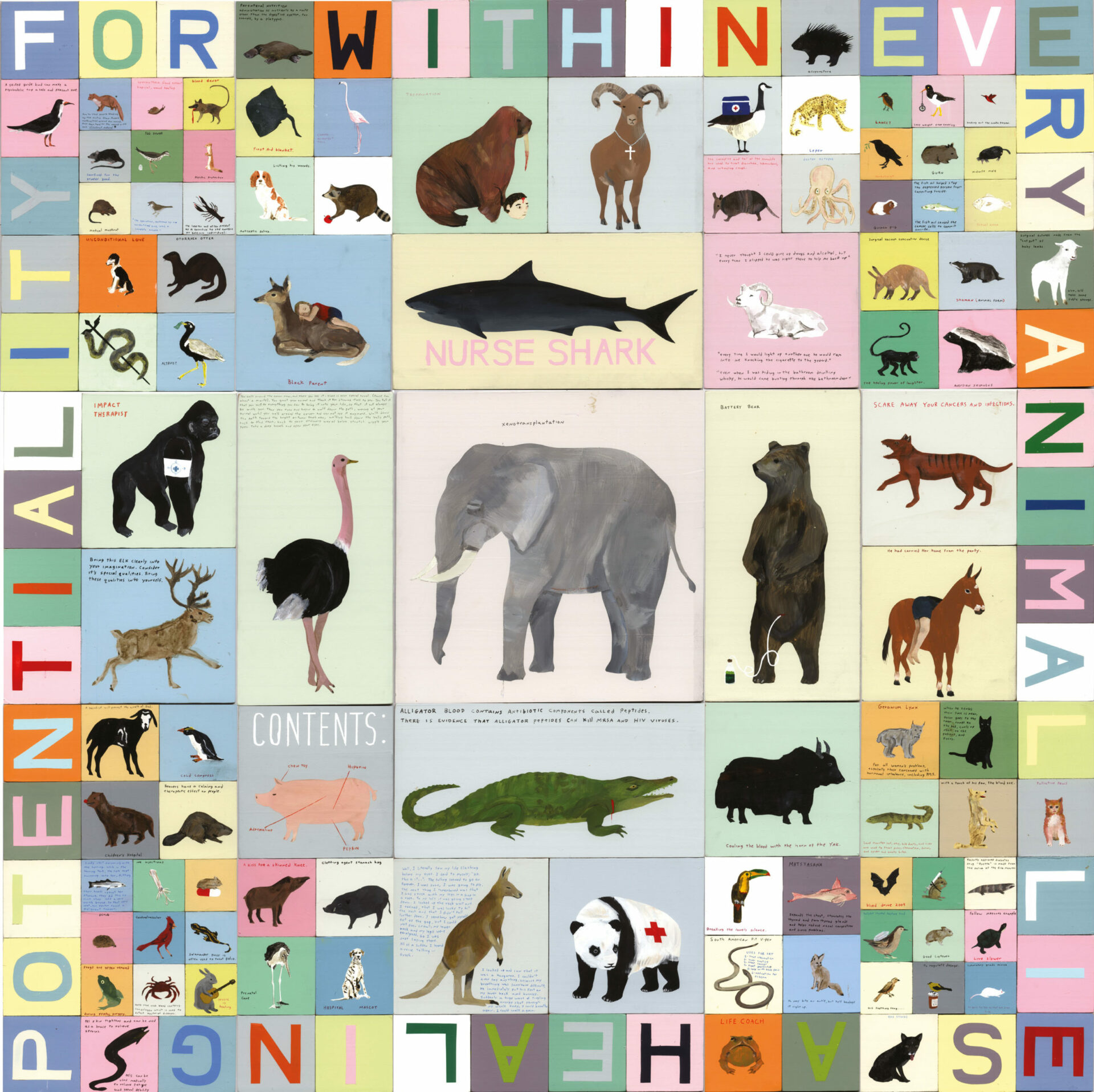

photo : permission de | courtesy of the artists & Richard Heller Gallery, Santa Monica

Painting has suffered at least half a dozen major existential blows since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, starting with Hippolyte Delaroche declaring “from today, painting is dead” in 1839, when he first set eyes on daguerrotypes. From this precedent, debate still abounds today as to whether photography, with its more effective means of documenting events and immortalizing faces as well as democratizing the whole imaging process — and now allowing anyone to embrace the once elitist talents of painters with a point-and-click camera — killed off painting.

There must be more to painting than the territories claimed by photography, since it certainly hasn’t lost any of its appeal to audiences, nor has it lost any market value. On the contrary, painting seems evermore the dominant commodity for commercial galleries, art fairs, and auctions. Of the ten top-selling artists at auctions worldwide, nine are painters.1 1 - Source: Blouin Art Sales Index, (accessed March 1, 2012), http://artsalesindex.artinfo.com. Each time painting is declared dead, more kudos and column space are dedicated to the deceased. If violent scenarios make for good television, perhaps the same is true in the art world. Today, so many paintings adorn the walls of art institutions that one is tempted to wonder if this art form was ever under serious threat, or if all this death talk was just an elaborate marketing campaign.

Although the livelihood of painting was supported in Quebec with events such as the Parti Pris de peinture exhibition/conference at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) in 1993, the timing of all the praise seemed a bit off, when indeed painting, on a global scale, had not been under such serious attack since the dawn of the Industrial Age. Throughout the 90s, much of the public imagination was captured by the digital revolution and, arguably, digital art was the only format (after acknowledging our postmodern condition) that could deliver anything new, at least in technical terms. In addition to the lens-based representational fidelity of photography, digital art added movement and interactivity to its range of expressive tools, along with the positivist agenda originally promised by the Moderns.

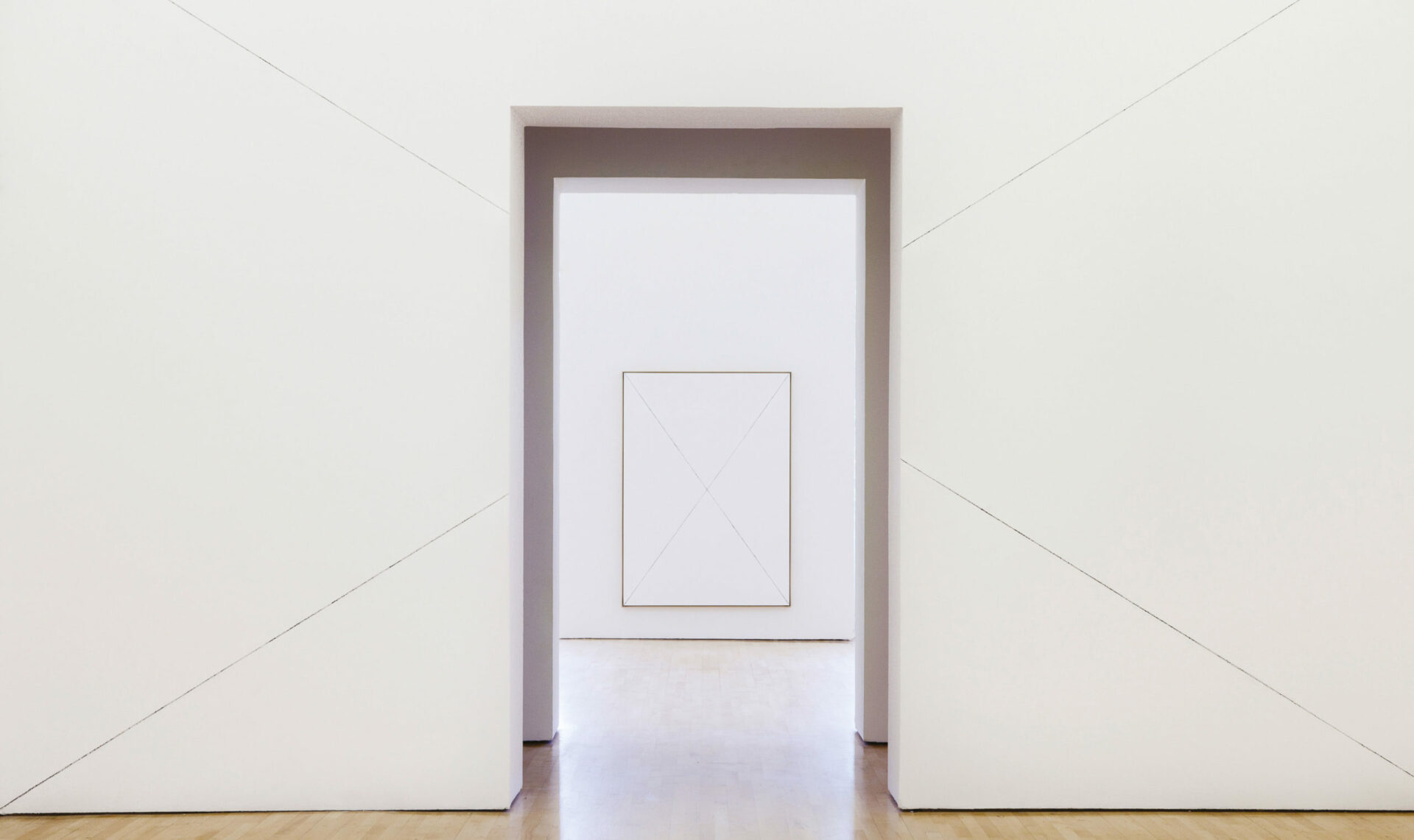

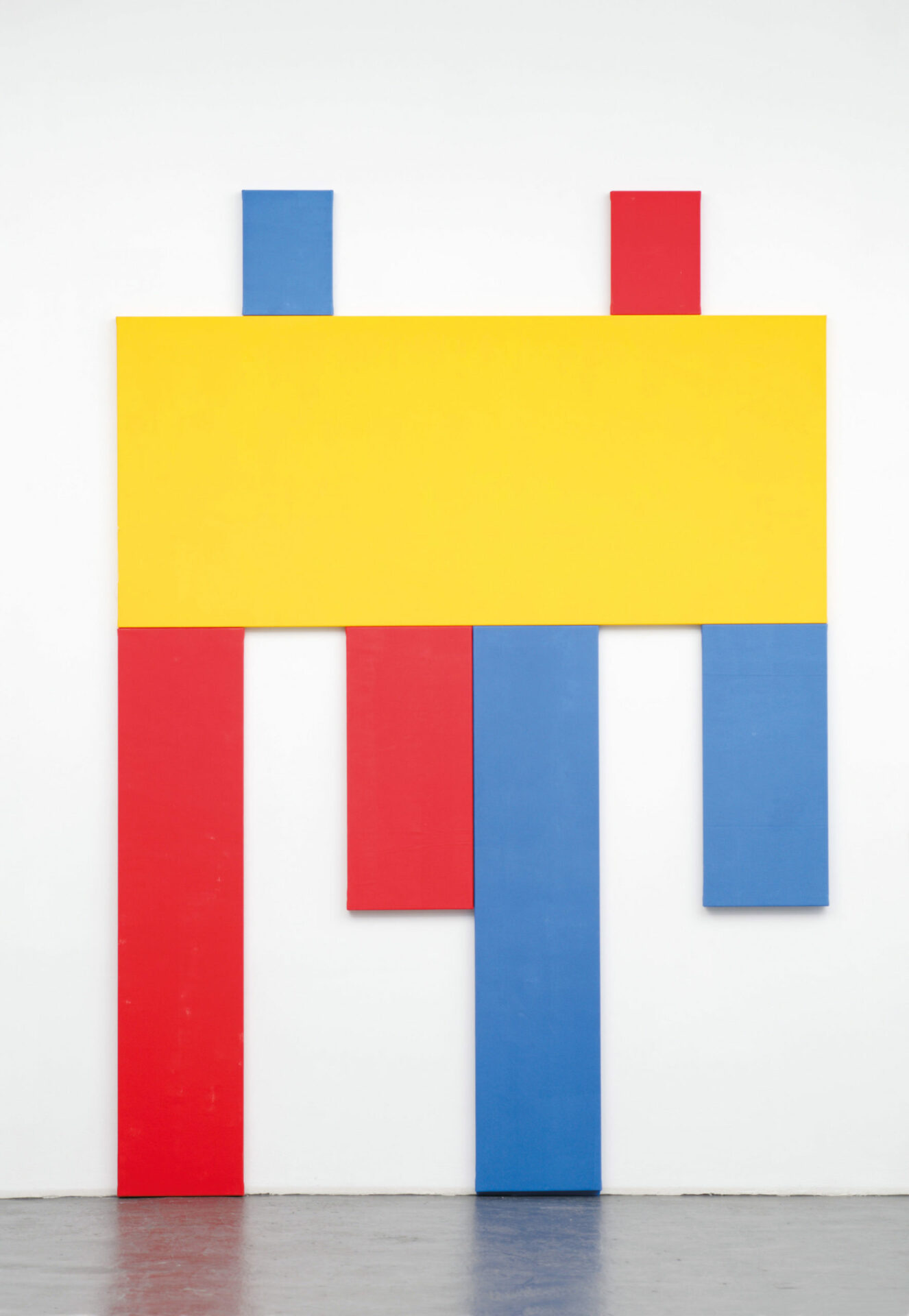

photo : Marc Blower, permission de | courtesy of Art: Concept, Paris & ICA, Londres

Helped by the fall of the Berlin wall, technocratic institutions rallied to revive the enlightenment project and make us believe the world was becoming incrementally better. Technology instigated the computer as the common denominator for all creative and organizational practices. In the form of clean energy, cheap manufacturing, and sustainable agriculture, technology promised to solve all the world’s problems. But the rude awakening of 9/11 shattered the last of our ideals about progress and left behind a worldview of ongoing conflict, and with it a disdain for extremist positions on any side of the exchequer. Similarly, in the creative world, pushing ideas to their ultimate logical conclusion was frowned upon. Thus, the failure of technology to carry a unifying narrative was self-fulfilling, because in accordance with Moore’s law,2 2 - Which states that every eighteen months, computers become twice as powerful, and half as expensive. technological art could not fence in its own specificity for periods of longer than eighteen months.

In its pursuit of optimizing digital images, Photoshop actually weakened photography’s documentary status by making pictures infinitely malleable: fashion models are routinely made thinner, with smoother skin, and “official” pictures are effortlessly manipulated (as first practiced by the Soviets in the 1930s) to edit out political liabilities. In addition, automated light adjustments in digital cameras make it too easy for hobbyists to take very good pictures, thus undermining the artistic merit of professional photographers. Indeed lens-based digital technologies most faithfully reproduce our visual experiences of the world, but commercial obsessions for new upgrades have transformed this format into the least archivable of materials. When looking at digital content that is just a few years old, we have become increasingly disappointed by its low resolution, its corruption by faulty hard drives, or the difficulty of opening images with the latest software. The constant nurturing process required to back up, upgrade, and remake this rapidly ageing content stands in embarrassing contrast to paintings that have traversed centuries, relatively unscathed. Longevity, rather than fidelity, might well be the winning criterion for painting to regain its documentary role.

American figurative painter John Currin famously said that he’s only as good technically as a mid-level nineteenth-century painter. That being said, one might as well ask to what level he aspires in terms of his choice of subject matter. Technology exposed the folly of reducing painting’s relevance to its representational means, and many have brushed off this initial death as a blessing in disguise, since it allowed painters to invent abstraction. After relieving themselves of the burden of commemorating historical events and affluent people, painters should have been free to focus on issues specific to the métier of painting. Instead of depicting the world visually, abstract painting could inform abstract thought and tune in with a philosophical vocabulary, as New York artist Peter Halley did when addressing Foucault and Baudrillard on his canvases. However, before getting too comfortable in abstraction, painters first need to respond to Marcel Duchamp’s “tubes of paint” argument (ironically first experienced by the Impressionists), as described by Robert Katz: “To fill the new tubes a whole new range of bright, stable colors began to appear on the market. The advancement of chemistry in the early part of the [nineteenth] century had heralded new colors such as cobalt blue, artificial ultramarine, chromium yellow . . . By the 1850s, the artist had at his disposal a palette more brilliant, stable and convenient than ever before.”3 3 - Robert K, Katz, Celestine Dars, The Impressionists Handbook: The Great Works and the World That Inspired Them (New York: Metro Books, 2000), 33.

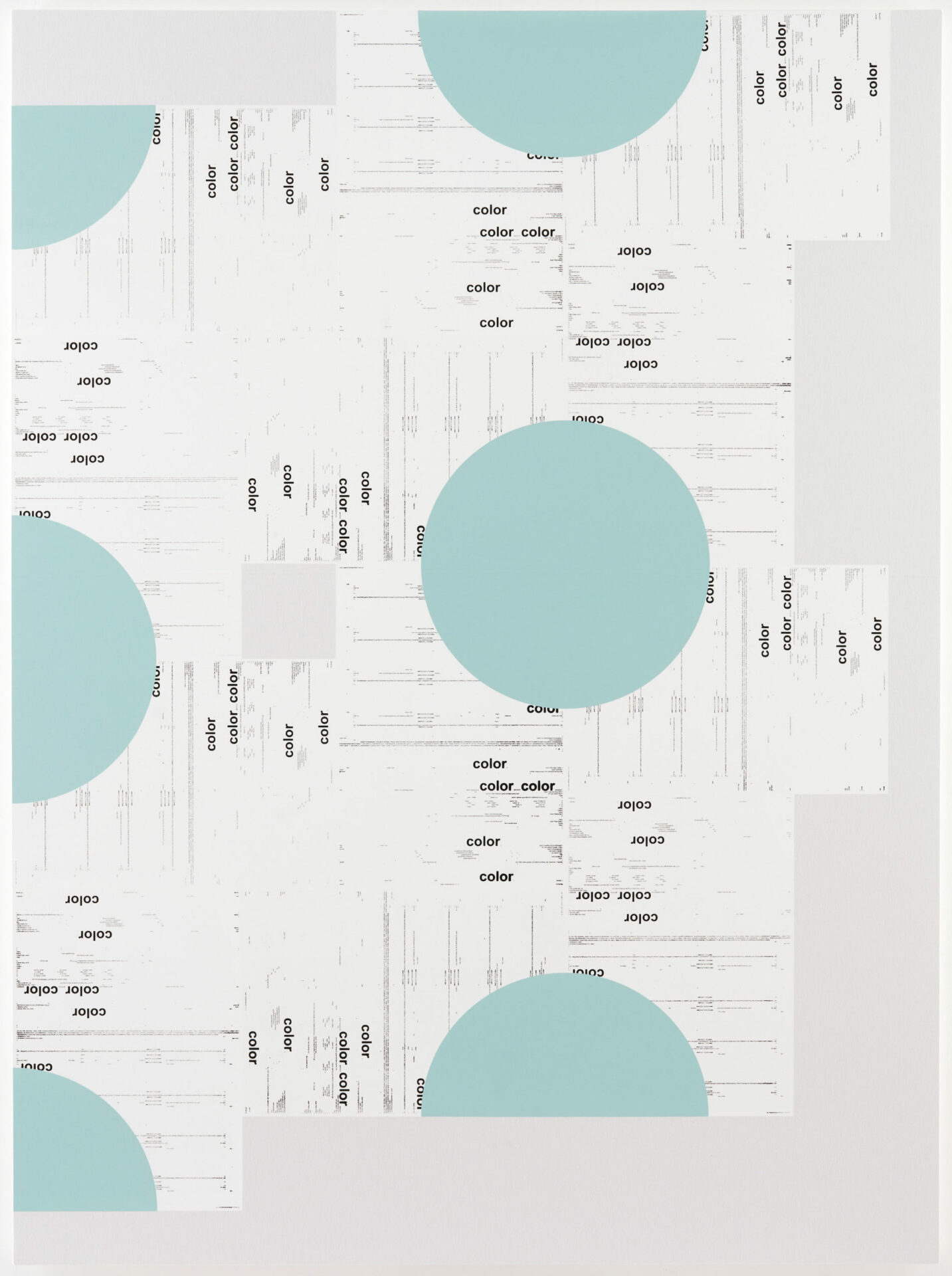

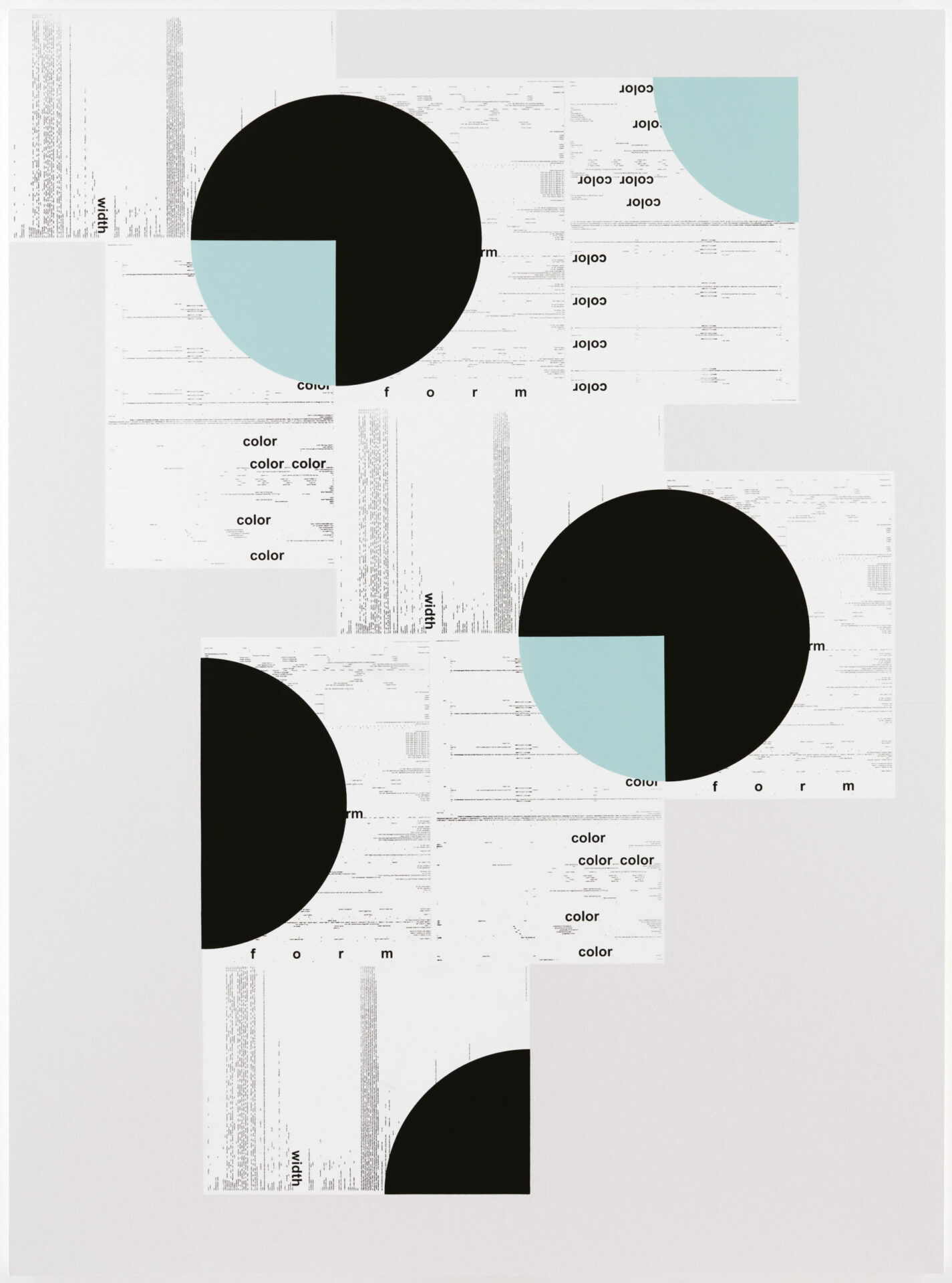

Joe Bradley, The Cavalry, 2007.

photos : permission de | courtesy of Peres Projects, Berlin

In stating that tubes of paint are actually assisted readymades, Duchamp implied that their use impacted the images produced. This is pretty much what Katz and others disputed about the industrial provenance of new, vivid, machine-made colours in prescribing the emergence of impressionism. Van Gogh, Cézanne, and other painters of this era increasingly applied unmixed paint, oozing straight out of the tubes, onto their canvases. With this in mind, how else should we interpret Claude Monet’s successive depictions of Rouen Cathedral, other than as assisted readymades avant la lettre, celebrating industrially enhanced pigment?

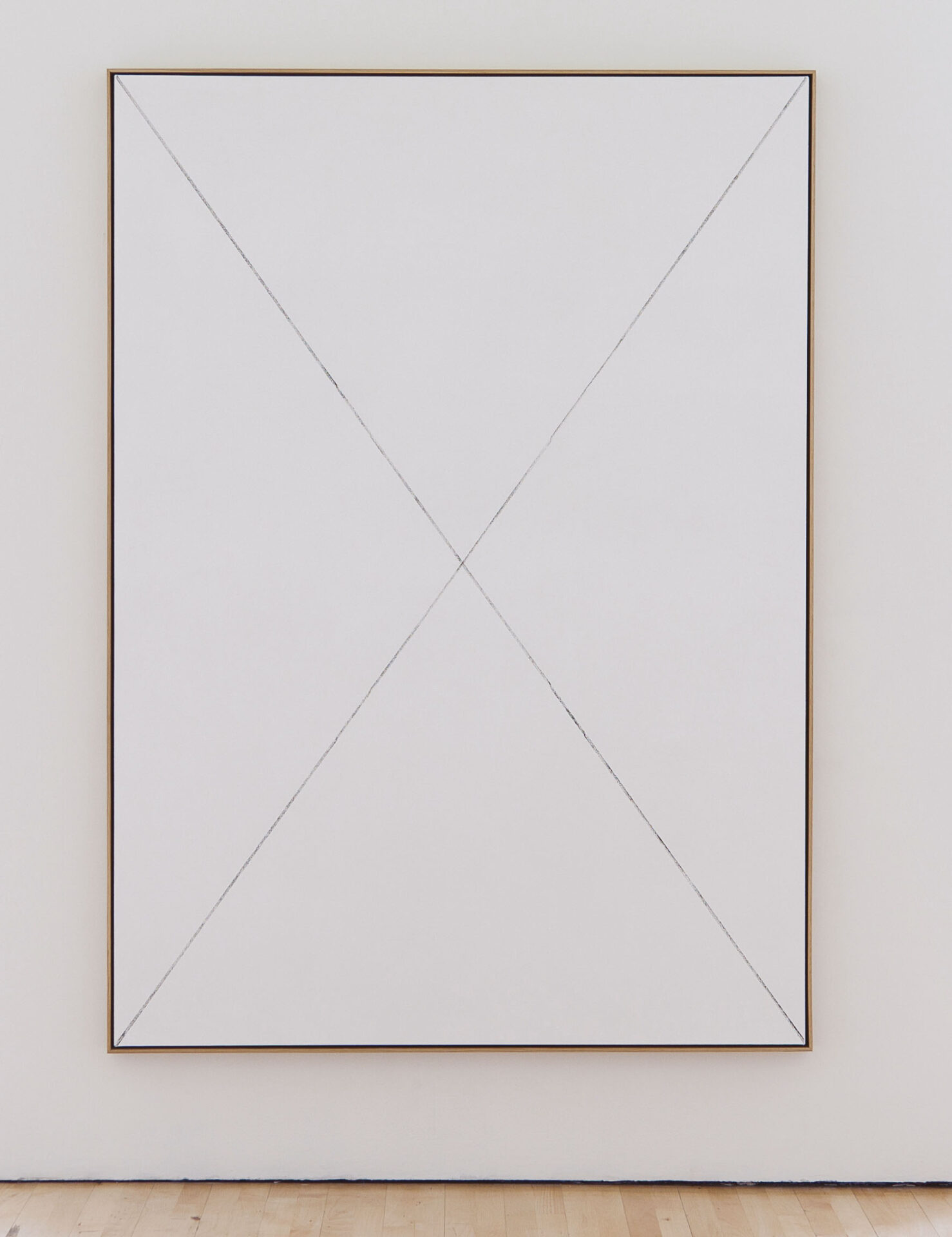

As art history repeated itself, the Impressionists’ lust for colour was readily pursued by the Fauves, and the Suprematists’ endeavour to take abstraction to its purest form was readily echoed by Minimalism, thus reducing the visual vocabulary to literal shapes. In 1965,4 4 - Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” in Arts Yearbook 8, (1965). Rpt. in Art in Theory: 1900 – 2000, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Maiden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005). artist/art critic Donald Judd prematurely dismissed painting on the basis of its illusionistic properties before realizing the enormous contributions Minimalism was making to painting in the works of artists such as Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Sol LeWitt. Even so, the self-imposed visual rhetoric of these artists created a negative iconography of unauthorized constituents: no image, no space, no story. Minimalist painting wasn’t killed off; it just attempted suicide by vacuum.

As if no crisis had ever occurred, Julian Schnabel encapsulated the 1980s revival of figurative painting with a simple one-liner: “I thought that if painting is dead, then it’s a nice time to start painting. . . . Painters will paint.”5 5 - Julian Schnabel in conversation with Max Hollein, “’80s Then” (series), New York, Artforum (April 2003), 59. But unbeknownst to Schnabel himself, he stepped right into the crux of the matter: by separating the actor from the activity of painting, he questioned the former’s subservience to the livelihood of the latter. In other words, he proposed the legitimacy of painters operating in a dead medium. Australian philosopher of language David Chalmers puts this issue in perspective with his “zombie argument.” While displaying all the external signs of sentience, Chalmers’ philosophical zombie experiences thoughts and feelings, but not within a unified conscience or subjective will. With this in mind, could painting be regarded as un-dead?

photos : permission de | courtesy of David Zwirner, New York

In response to the zombie argument, and with the irony of a devil’s advocate, one could argue that the successful death of painting actually adds credibility to its cause, akin to the practice of martyrdom. In death, did painting find more followers than in its lifetime? How very Christian. In a convenient twist of fate, these issues now invite debate about the dualist nature of painting; on the one side materialist, sensitive, and on the other side spiritual, cognitive. In short, two invertible types of painters emerge from this dualism: the painter of substance, determined to find a subject matter that would warrant her ongoing obsession with painting; and the painter of ideas, experimenting with other media, but eventually returning to painting to find the most efficient presentation format for her pre-selected subject matter.

To break from the shackles of dualism as well as engage with our non-Western neighbours on this globalizing planet, painters should today propose a middle way,6 6 - A Buddhist term describing the moderated path between the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortifying asceticism. a third type of practice which stands halfway between the outermost positions of painting’s pendulum cycle, where its swing is at its most energetic. Appropriately enough, painters such as Joe Bradley, Jacob Kassay, Michael Riedel, and many more are emerging today, mixing sensuality and rigour, precision in language, and a certain bravado without bullshit. Closer to home, we may even find a fourth kind of painter, exemplified by Winnipeg’s Michael Dumontier and Neil Farber, or Montreal’s Janet Werner: in their immediate environment resided brushes and canvas, and for no reason other than proximity, conjuncture, and force of habit, painting has been arbitrarily recaptured as a utilitarian engine of self-expression.

photo : permission des artistes | courtesy of the artists

photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de | courtesy of the artist

& Parisian Laundry, Montréal

After zombies and martyrs, painters may turn to the phoenix as the definitive metaphorical figure to service their profession. Not one to shy away from the prospect of its own demise, the flaming death of the phoenix essentially announces the start of a new life cycle, through a rebirth from its own ashes. As the Egyptian Phoenix is identified with the sun god Ra, shouldn’t we be surprised to see painting rise again in all its grandeur and shine across the art world sky, only to crash into the horizon before dazzling yet another day? Certainly a noble metaphor, the phoenix/painting is dramatic enough to pull some chords of empathy. However, each passage should still deliver a singular presence — perhaps as the sun’s height on the firmament marks the seasons — and avoid exhausting our attention. And so, as we follow painting’s predictable fate in the future, we should at least appreciate its journey.