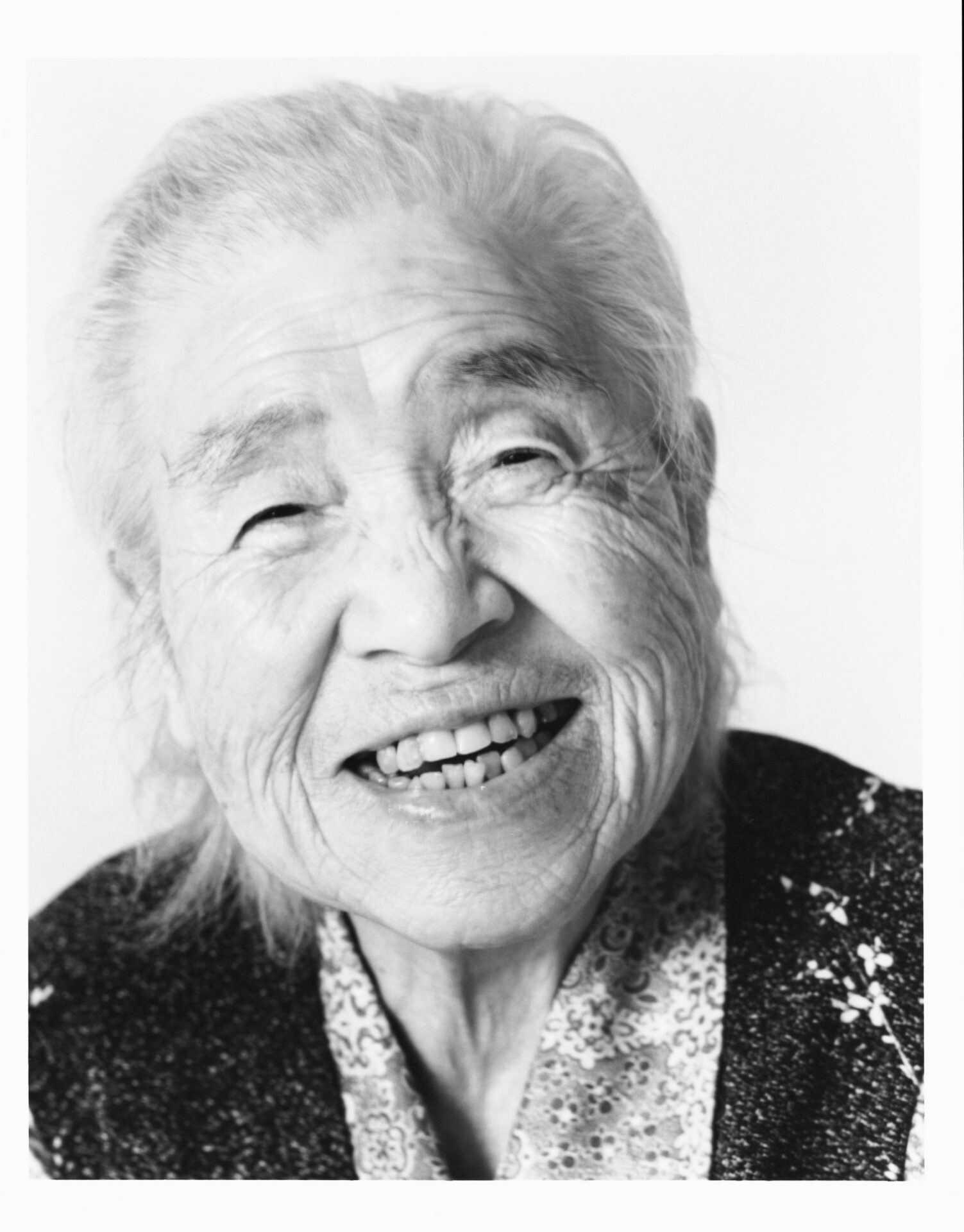

photo : Imai Norio

What these forms [the collection and the series] indicate, and what photography recalls, wrought by multiplicity right down to the film, is the simple fact that the image is never alone.1 1 - André Gunthert, “L’objet sans qualité,” La Recherche photographique, special “Collection, série” issue, No. 10 (June 1991): 12.

In the 1970s, assuming from the start that their series could only gain meaning through quantity and repetition, some Japanese photographers produced vast sets of portraits composed of hundreds of pictures. Primarily based on an indexing of the real and the accumulation of documents, their work bore powerful connections with the art scene in New York City, where some of the most influential Japanese conceptual artists were based — Kawara On, Ono Yôko, and Arakawa Shûsaku2 2 - Japanese names are given according to common usage in East Asia: surname followed by first name. then resided in New York City, along with photographers Ohara Ken and Sugimoto Hiroshi. These practices are echoed in recent artistic productions of the 1990s and 2000s that revive an interest in the listings and enumerations that conceptual artists expressed. The book often becomes the favoured medium for presenting these images, more on account of its formal properties (to be identified here) than on narrative ones. One need not list all Japanese works assembling portraits — they are too numerous and too diverse; I focus instead on a few significant publications that associate repetitive page layout with photographs derived from studied, methodical picture-taking.

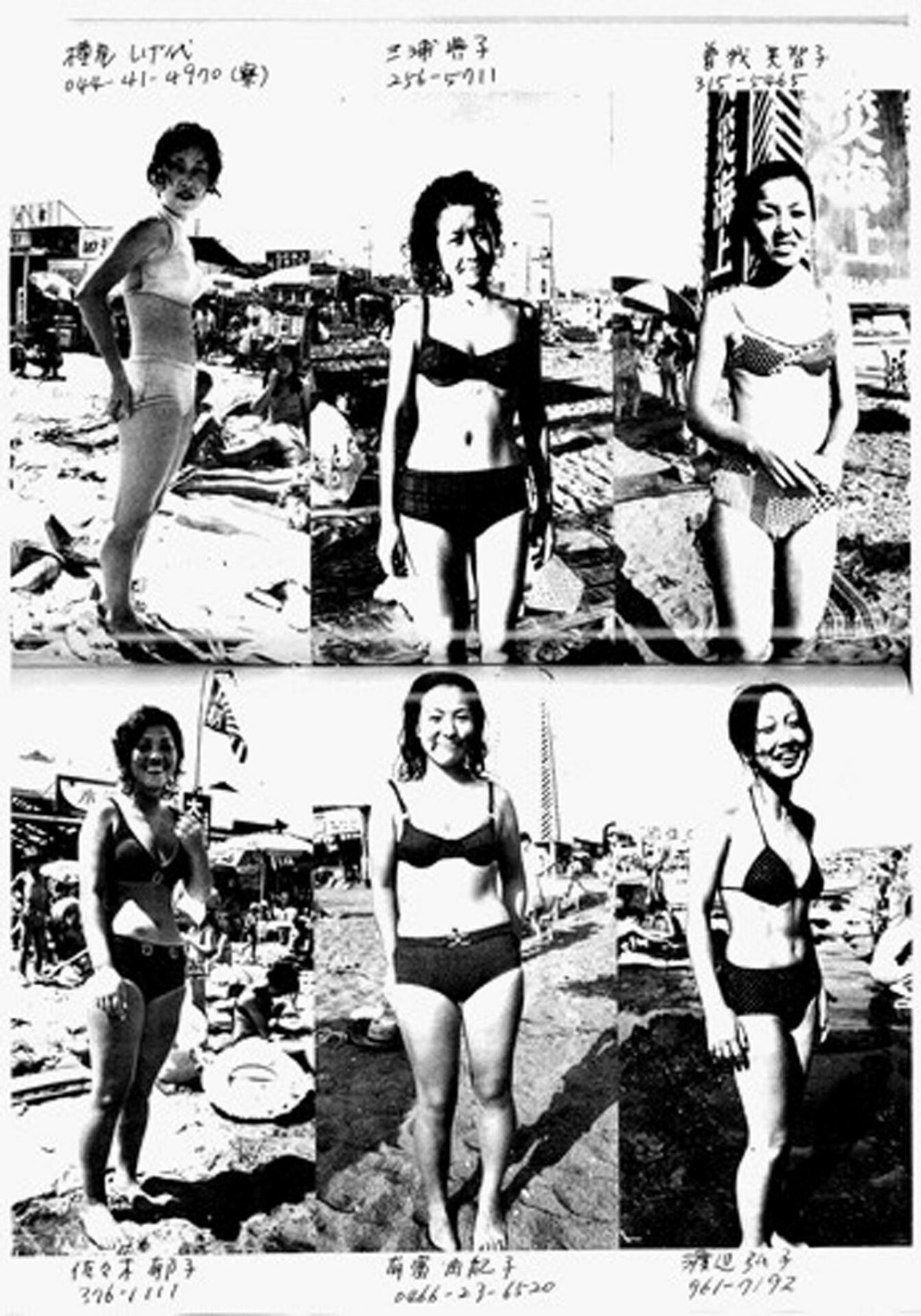

photo : Geribara 5

Ohara Ken’s One (1970) is composed of 504 photographs that take up the entire page, each presenting a frontal close-up of the expressionless face of a man or a woman. Through elaborate reframing, facial features — eyes, nose, mouth — are made to occupy exactly the same position in each image, rendering the faces interchangeable.3 3 - On the framing of the images, see Sally Stein, “Face to Face: Ken Ohara’s Close Encounters with Photography,” in Ken Ohara: Extended Portraits Studies (exhib. cat.) (Göttingen: Steidl, 2006), 71. Ohara preferred male subjects to be close-shaven, and the women without make-up, blurring physical particularities and processing the images such as to attenuate differences in skin colour. In the succession of bleed photograph pages, all the subjects come to look like each other, lose their uniqueness and become one, as the title suggests. One is also suggestive of the phone book’s vast compilation of names and identities, particularly the Manhattan phone book, whose dimensions and thickness it emulates. Thickness is significant: for the message to have weight, the snapshots must be numerous and the book heavy.

A directory of a completely different kind is the one proposed by the photographers’ collective Geribara 5, in 1971, with its intentionally frivolous Mizugi no yangu redi tachi (Young Girls in Swimsuits).4 4 - Active in the 1970s, this group of photographers was composed of six members, of which Araki Nobuyoshi was the better known. The work is composed of 306 portraits of young women on the beach, six per two-page spread, grouped by types of poses: feet in the water, sitting on towels, standing toward the sea, etc. This publication’s particularity resides in the handwritten inscription of the model’s name beside each portrait, along with either a phone number or an address.5 5 - Araki states that only half the information was real. Araki Nobuyoshi, Shashin no hanashi (Photography Lesson) (Tôkyô: Hakusuisha, 2005), 76-77. The photo’s author, on the other hand, remains anonymous. The group predominates, suggesting found or amateur photographs, an impression reinforced by the banal and conventional nature of the seaside scenes. All that matters in this collection of images is the model’s pose, for that is what justifies the photograph’s inclusion among the others.

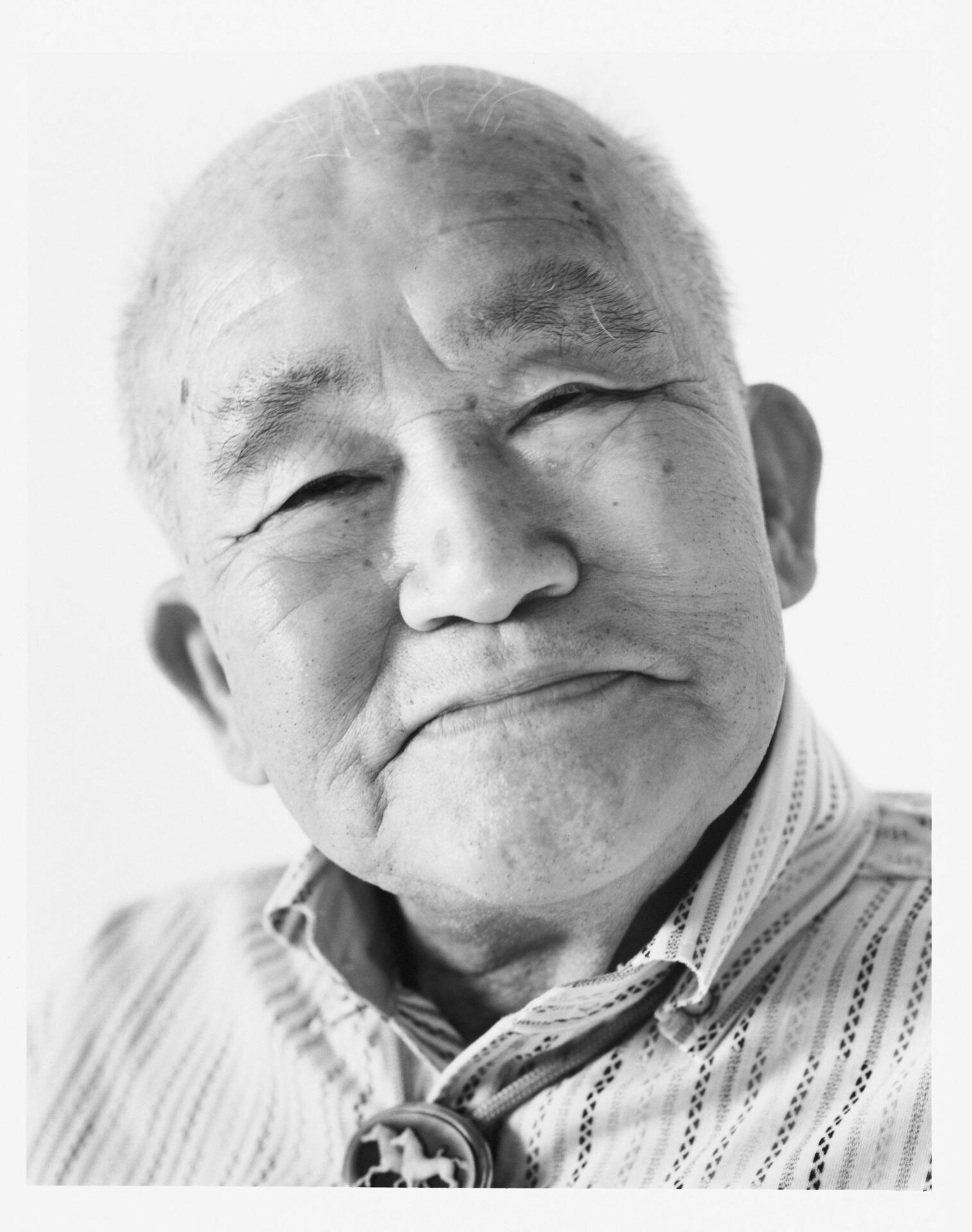

Araki Nobuyoshi, The Faces of HIROSHIMA,

projet Nihonjin-no-kao project, 2009.

photos : © Araki Nobuyoshi, projet The Faces of Japan project

In these two books, a sense of repetition is created by the page layout and by the sheer number of images, palpable in the thickness of the work. Indeed, Ohara’s images would not be as effective if they were not framed to resemble each other, and those of the Geribara 5 collective only gain significance through the juxtaposition of similar poses. One of the Geribara 5, Araki Nobuyoshi, initiated a project to document and photograph the residents of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures. His approach, like that of One and Mizugi no yangu redi tachi, recalls photographer August Sander’s survey and photographic compendium of German society, to which Araki directly refers in his artist statement, citing Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts as a model.6 6 - This text is partly reproduced in Watada Susumu, Story A: Tensai Arâkî no satsuei genba (Story A: News of Araki the Genius) (Tôkyô: Shinpûsha, 2007), 54-55. Begun in 2001, Araki’s project, Nihonjin-no-kao (Japanese Faces), now comprises nine 500-page volumes of individual and group portraits.7 7 - The prefectures covered in the shots are Ôsaka (three volumes), Fukuoka, Kagoshima, Ishikawa, Aomori, Saga, and Hiroshima. A website is dedicated to the project: www.j-face.info. The whole is sufficiently dense to present a marked formal repetition, accentuated by uniform lighting, relatively homogeneous poses, and the use of a mobile studio suppressing all decor. The levelling effect of the snapshot presentations, reinforced by the multitude of images, creates a sense of anonymity, even as the photographer identifies the models by age and profession at the end of the work.

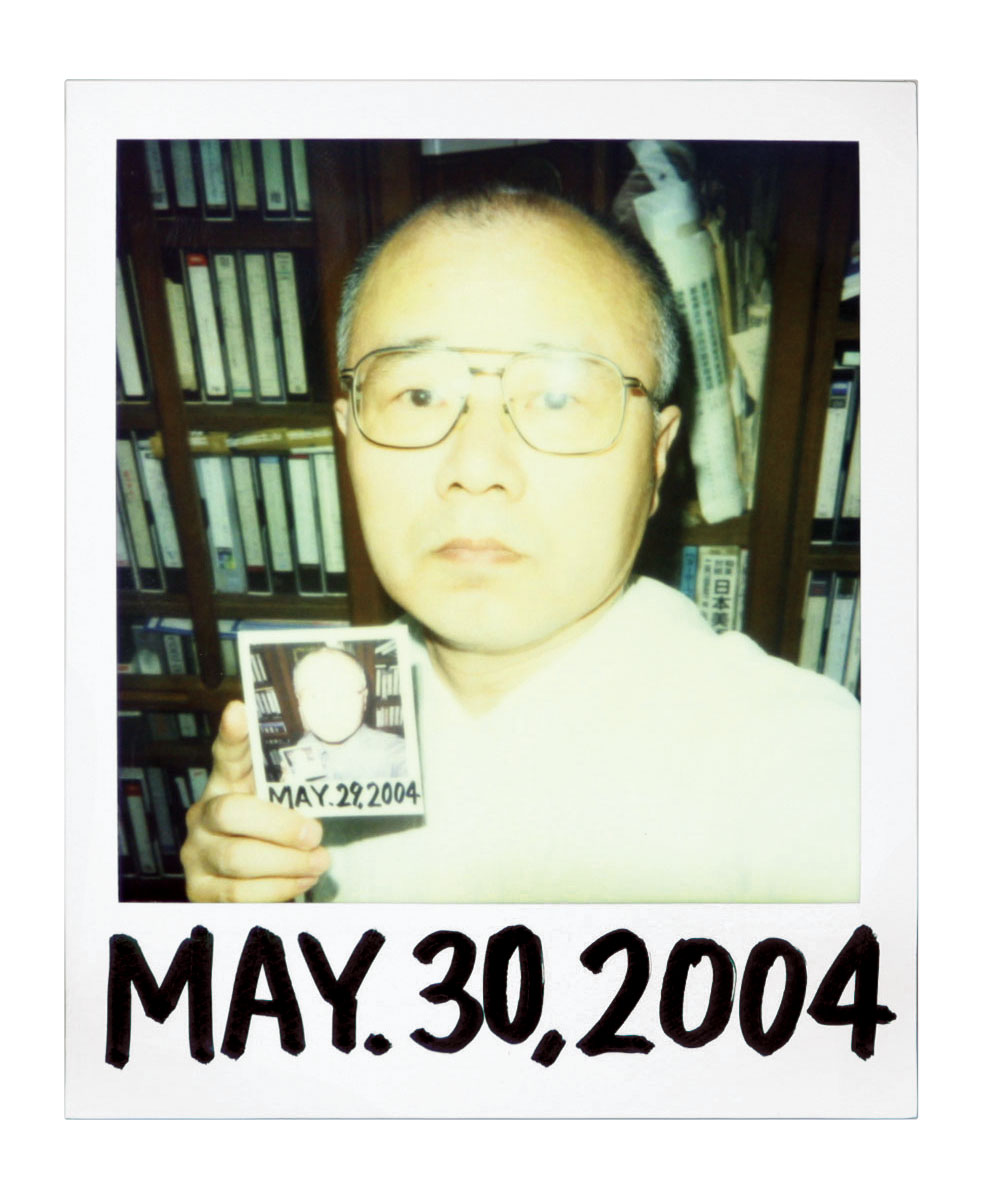

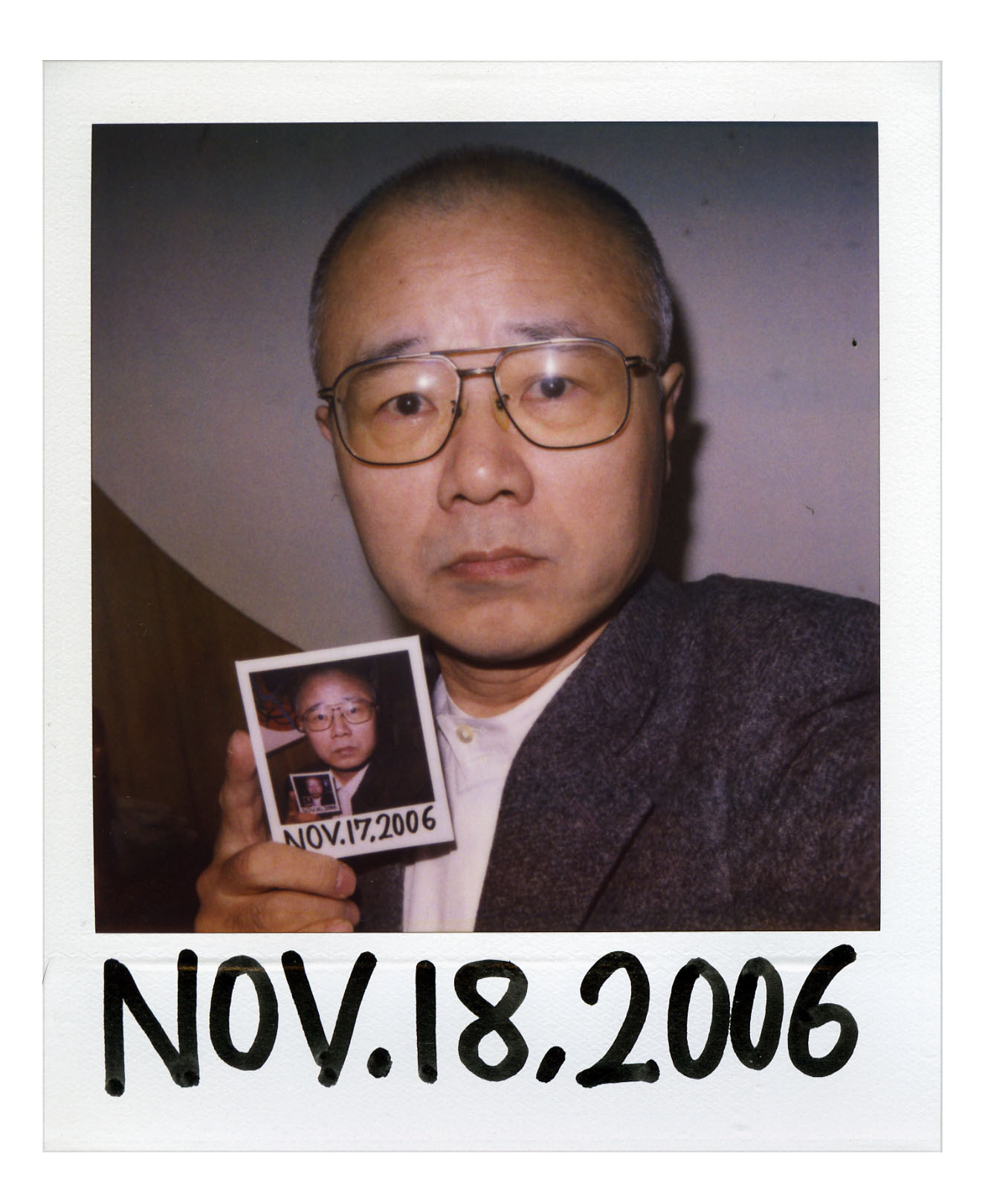

en cours depuis 1979 | ongoing since 1979.

photos : Imai Norio

Rather than compile a compendium of humanity, Imai Norio focuses on the photographic self-portrait. Every day since May 30, 1979, he has taken a Polaroid photo of himself, then written down the date of the shot below the print. The day after, he takes a picture of himself holding the camera in one hand and the snapshot of the day before in the other, in the same position. Here the temporality running throughout his work is expressed at once by the felt-pen inscription of the date and the recurrence of the self-portraits, day after day — , the artist himself calling these shots “self-portraits of repetition.”8 8 - Imai Norio, “Sakuhin shashin to shashin ni yoru sakuhin” (“Photography as work of art and the work of art created from photography”), Bijutsu techô, No. 462 (March 1980): 136. Through minute variations in haircut and clothes, we see the artist ageing as he re-actualizes his face every day. Imai first displayed his self-portraits piled in Plexiglass boxes — one per year, with only one image showing on top, that of December 31st of the year in question, manifesting time in a succession of layers resembling geological strata. The artist wasn’t trying to express the passage of time, but rather, in his words, its “thickness.”9 9 - Imai Norio, cited in Fujii Hisae (ed.), Gendai bijutsu ni okeru shashin. 1970 nendai no bijutsu wo chûshin to shite (“Photography in contemporary art: Of art in the 1970s”) [exhib. cat.] (Tôkyô: National Museum of Modern Art, 1983), 46. He waited until 2006, when he had gathered enough images to publish a work from the series: Derî pôtoreito. Shihanseiki. Kioku no nkki (Daily portrait. Quarter century. Diary of memories). The work contains approximately 9,000 images, presented either singly on a page or in a grid of 36 or 144 shots per page, thus emphasizing a sense of proliferation. The grid has the advantage of proposing a clear, rigid structure, capable of ordering the repetitive images without imposing a hierarchy.

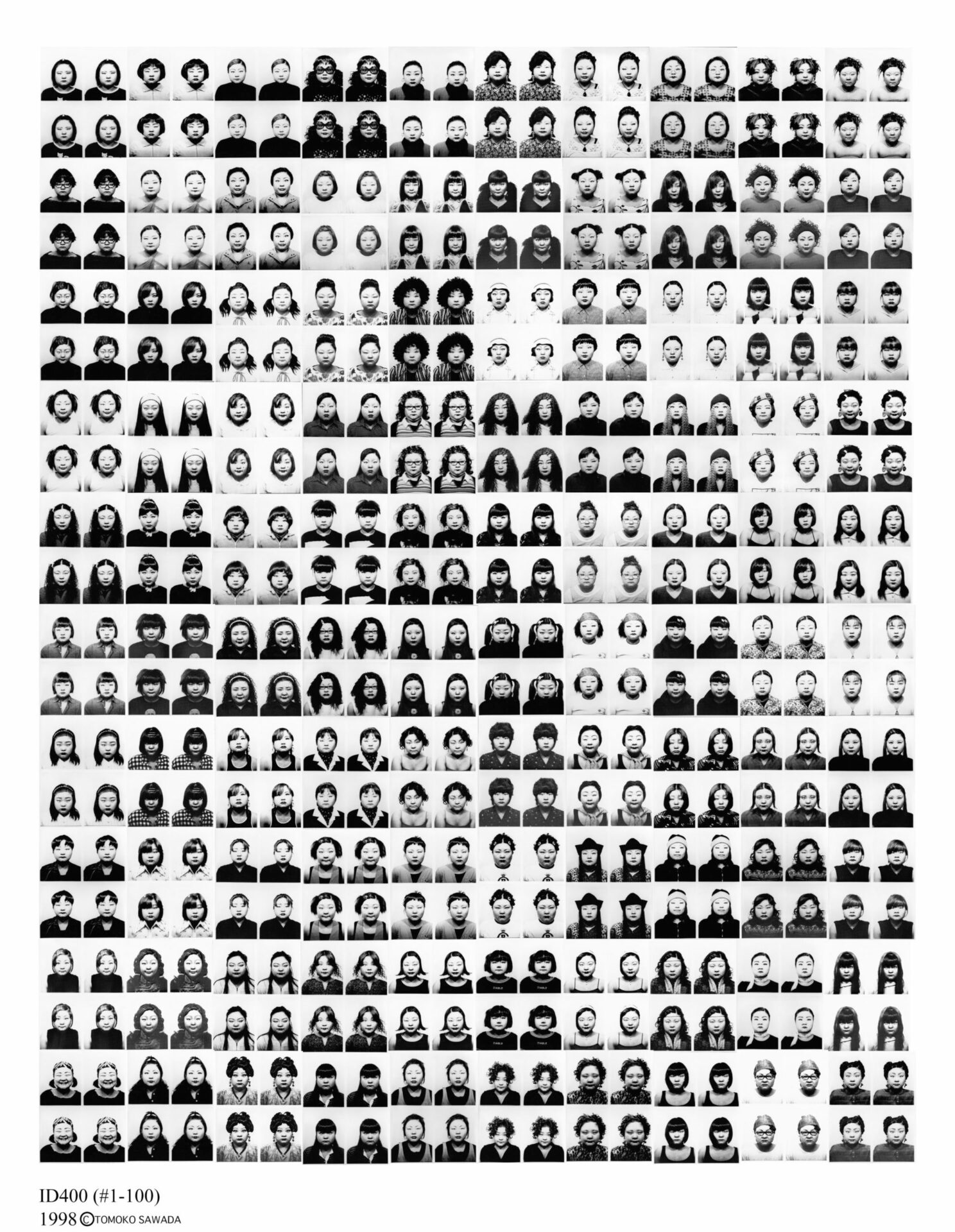

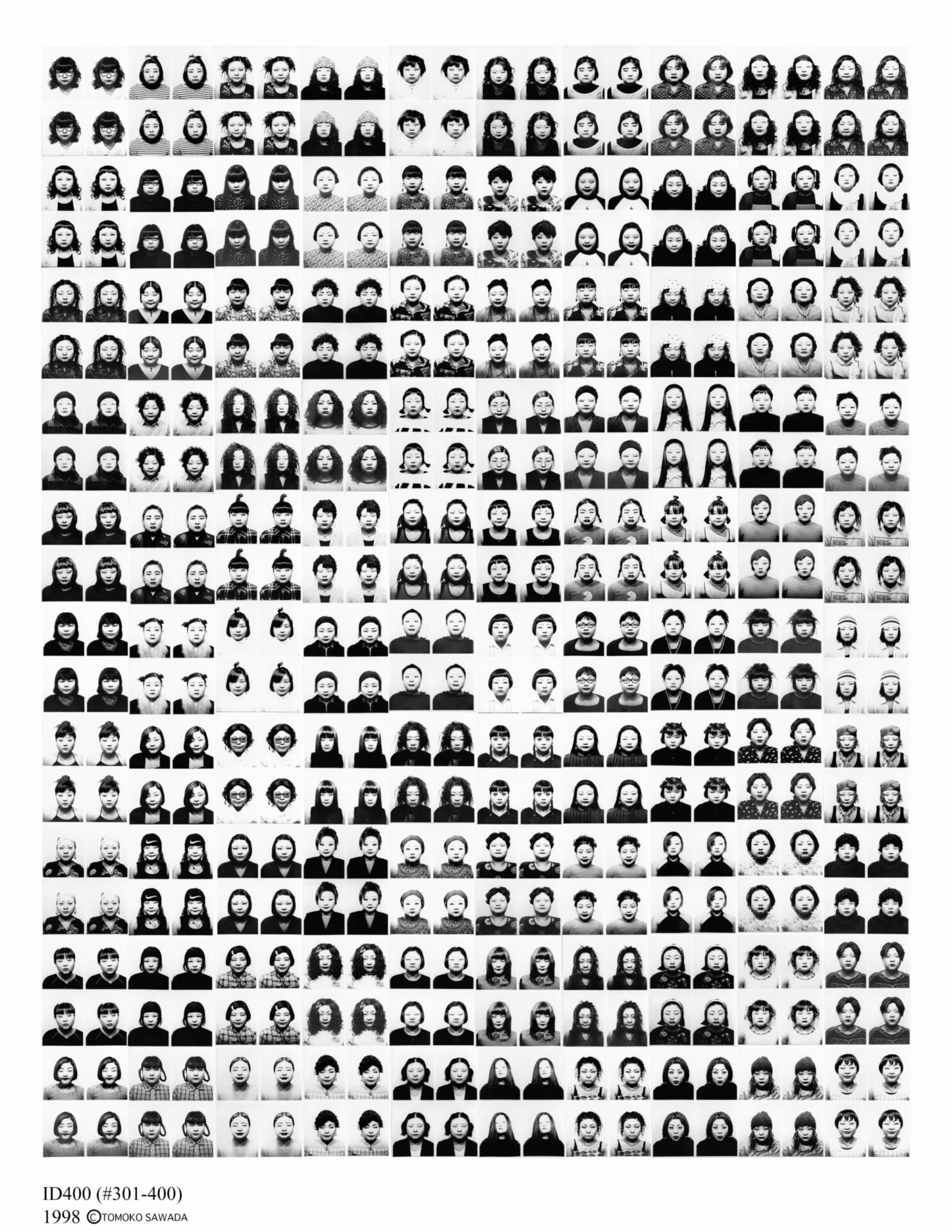

Grids of photos are also to be found in Sawada Tomoko’s book ID400 (1998), which brings together 400 sheets of black and white photo‑booth shots. The thick, small-format book (15.4 x 11 cm) reproduces one sheet per page on a 1:1 scale. The same face appears on each page, but with subtle differences: in order to get around the sameness of the photographic self-portrait, Sawada changes hairstyle, clothes, make-up and facial expression. Whereas the photo ID is meant to readily identify the person represented, here it butts up against the difficultly of representing the reality of facial features. The book has the virtue of reproducing the material aspect of the photos, in contrast to the artist’s exhibitions, where the sheets are printed large scale, thus losing the photo-booth’s characteristic four-part strip. Similarly, in the book School Days (2006), Sawada presents class photos in which she interprets all the students and teacher: the photographs are printed on bristol board, recalling the support commonly used for mounting classroom photos, while the large-scale exhibition prints obliterated such relationships with the referent.

photo : Sawada Tomoko, permission | courtesy MEM,Tôkyô

In line with the idea that “photography doesn’t adapt very well to the singleton [and that] it’s hard to make out a photographer’s art from a single image,”10 10 - Philippe Arbaïzar, “Le livre de photographe,” Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, No. 81 (Fall 2002), 51. these Japanese artists generate hyperbolic accumulations, multiplying their snapshots by the hundreds and even thousands. The repetitive effect is emphasized by choices made during the shooting and in post-production: recurring shots, nondescript settings, use of black and white,11 11 - While Imai’s Polaroids were first shot in colour, they were printed in black and white. In contrast, with Yoshida Kimiko’s works, whose identically composed self-portraits are in colour, one realizes the unifying power of black and white in these portrait series. very close shots that show as little clothing as possible, and so on. Particular attention is given to page layout so as not to create an assemblage of independent images, but a unified set of similar ones. Indeed, though these practices are founded on either multiple captures or a concern for enumeration, a reading of these books suggests a prevailing homogeneity.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]