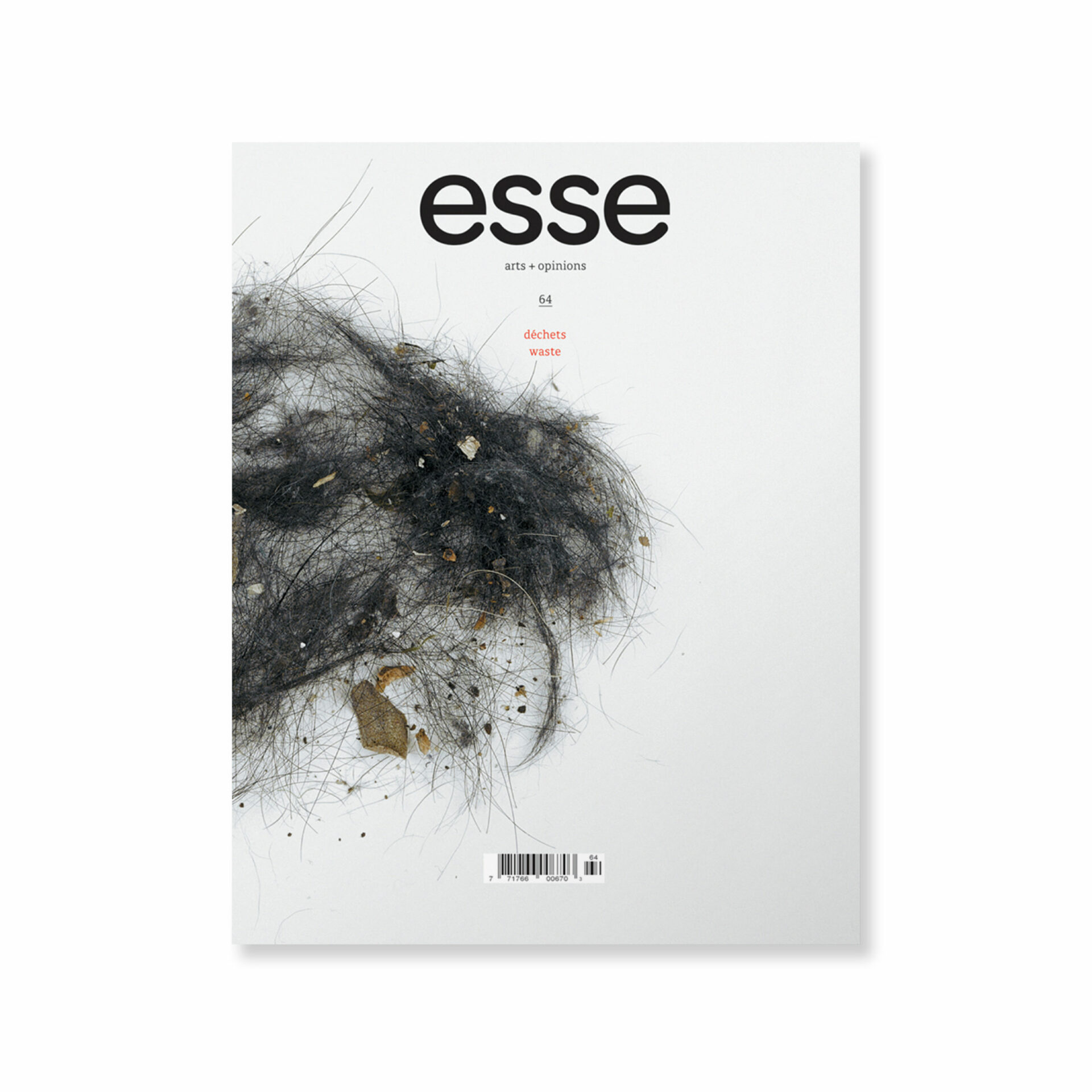

Waste: Inspiration or Expiation?

The presence of waste in contemporary art certainly doesn’t have the same provocative impact as when the avant-gardes used it at the beginning of the twentieth century. Similarly, the debunking of the art object through the use of “poor materials” instead of “noble materials” makes little sense at a time when garbage bins, landfill sites and drop-off centres have become the new suppliers of artists’ materials. However, the collection of discarded items, the transformation of rubbish, scrap or refuse—pick your designation—and the use of waste as subject matter for photography are recurrent practices in today’s art. What does this gesture mean nowadays? Has provocation been replaced by exposure?

Now that waste accumulation has become an increasing source of worry and that recycling is no longer just an option, the ecological question certainly stands out in the association between art and waste. Moreover, one could read in this encounter a critique of consumer society. In the last decades, we have witnessed the production—in excessive quantity, at infernal speed and, moreover, at a cheap cost in Chinese factories—of objects that are more readily discarded than repaired. As a result, the supply in material resources is particularly easy for the gleaner artist—a sad privilege. Our intention is not to state a situation of which we are all aware.1 1 - Those who are not that aware might want to consult a very lucid book written by astrophysicist Hubert Reeves, Mal de Terre, a dark yet realistic portrait of the current state of the Planet, with a rather exhaustive description of various forms of waste that have disastrous consequences on the environment. Hubert Reeves (with Frédéric Lenoir), Mal de Terre (Paris, Seuil, 2003). Twenty-first century citizens, including artists, are certainly the most informed in the history of humankind. However, they continue to consume massively as if this state of affairs were unsolvable or as if it were the price to pay for our species’ comfort. Obviously, we cannot blame the sole production of waste for all our environmental problems—even if the word refers not only to domestic garbage but also to industrial and toxic refuse, etc.—but neither can we entrust the task of finding a solution to citizens only. As mentioned in a excerpt from Libération quoted by Éloïse Guénard on page 16 of this issue, “While attributing culpability to citizens and in proposing a facile expiation of their sins by means of small, individual gestures, we forget to explain to them that a good number of the public policies to which we subscribe are anti-ecological.” While we should not, at the risk of destroying any sense of individual responsibility, give the impression that personal gestures have no impact on the environment, can we expect significant change to happen if our leaders don’t take drastic measures?

The previous paragraph might suggest that this issue has a strong ecological content. It is not however the main perspective privileged by our authors. It doesn’t mean that such preoccupations are not echoed in their essays but rather that they chose to consider waste for what it is, i.e., a meaningful object, with an important cultural and historical background, which has the potential to make us think and the capacity to be transformed into an artwork. Some examples of such work can be seen in our portfolio section, where artists, in the descriptions they give of their work, show that beyond aesthetic concerns they want to question lifestyles that lead to the overproduction of waste. In her book Quand les déchets deviennent art, Lea Vergine writes: “Trash is a direct, meticulous and indisputable document of the habits and behaviours of those that produce it, that goes even beyond their own convictions or self-perception.”2 2 - Lea Vergine, Quand les déchets deviennent art. Trash, rubbish, mungo, (Milano: Skira, 2007). This sentence encapsulates rather well this issue where waste, in its multiple forms and locations, and the artworks derived from it show us a bit more who we are.

[Translated from the French by Colette Tougas]

I take this opportunity to salute André Greusard who has left the esse team to devote himself to personal projects. A founding member of the magazine, André was involved for nearly twenty-five years as a writer, editor and board member. On behalf of the team and myself, I thank you, André.